Memo Published October 20, 2015 · Updated October 20, 2015 · 18 minute read

Local Examples: Innovations in Recovery from Serious Mental Illness

Jacqueline Garry Lampert

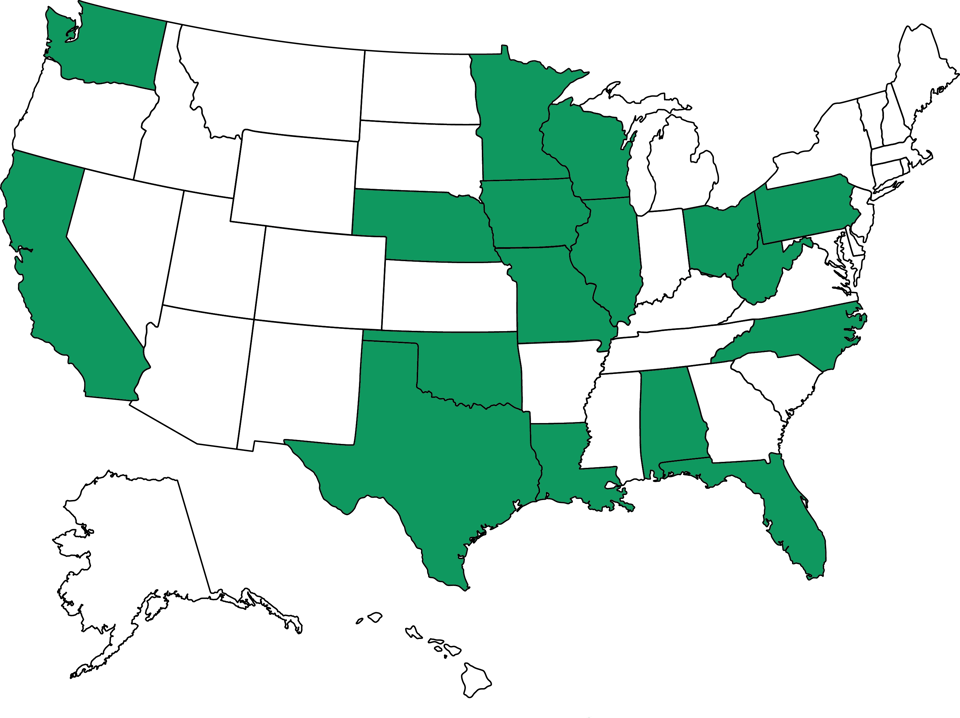

Institutionalization doesn’t have to be the answer for Americans with serious mental illness. Across the country, providers are using a community- and team-based model of care called assertive community treatment (ACT), which meets patients’ needs for basic life necessities as well as treatment to reduce hospitalizations, increase housing stabilities, and help patients live an independent, productive life.

For example:

Alabama

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Paulette Lee was homeless, completely disconnected from her family, not taking her medication, and hearing and reacting to voices in her head before she connected with the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Research and Evaluation of Assertive Community Treatment (REACT) team. She’d been arrested, in her words, “four or five times at Greyhound,” where she’d tried to spend the night. But after connecting with the REACT team, Alabama’s first team offering assertive community treatment services, she was adhering to her medication regimen, living independently, and reconnected with her family. The REACT team reports that most of their long-term patients avoid psychiatric hospitalization and very few return to jail once they engage with the program.

California

MHA Village

MHA Village is a program of Mental Health America of Los Angeles located in Long Beach. “The Village,” as its known, is not a residential program, but offers case management and rehabilitation services for individuals with severe mental illness, whom the Village calls ‘members’. The Village utilizes what it calls a “full service approach”—members are assigned to one of three “neighborhoods,” each of which has a director, assistant director, psychiatrist, financial planner, community integration specialist, and nine personal service coordinators. These personal service coordinators are not assigned a caseload, instead they serve all members in the neighborhood. A separate homeless assistance program serves people who are homeless and have mental illness, aiming to connect people with services to address their housing and health care needs. The program both conducts street outreach and operates a drop-in center offering information and referrals, showers, laundry, clothing, a place to receive mail, and more.

The Village’s medical director, Dr. Mark Ragins, describes seeing Village members accomplish things that his professional experience and training led him to believe were not possible. For example, Dr. Ragins describes Dan, who lived in a board and care home for 15 years and wanted to move into his own apartment. Dan was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and often complained about the people in the alley preparing to attack him. Everyone involved in his care, including his family, felt he was too ill to live independently. Everyone, that is, except his 60-year-old caseworker, Clara, who told everyone that she worked for Dan, and if Dan wanted an apartment, she was going to get him one. Working together, Clara and Dan found an apartment, and Clara helped Dan plan a housewarming party. Several months later, Dan called The Village in a panic, saying poison gas was being pumped into his apartment. Everyone involved in his care knew this was the relapse they were expecting and prepared for Dan to be hospitalized. Everyone, that is, except Clara, who went to his apartment, found a leak in Dan’s gas pipes, and moved Dan into a hotel while she got the landlord to fix the pipes.

Telecare Corporation

Founded in 1965, Telecare Corporation is an employee- and family-owned provider of services to individuals with serious mental illness. Telecare operates Steps Toward Recovery, Independent, Dignity, Empowerment, and Success (STRIDES) in Alameda County California. This assertive community treatment program focuses on individuals with severe mental illness who, without the program, would require an institutional-level of care. STRIDES has been in operation since 1994 and provides 120 members, some of whom have been with the program since 1994, with 24/7 access to a STRIDES team member. A four-year evaluation of STRIDES found these clients spent a total of 1,971 days in institutions, compared to 15,036 days spent in institutions by a comparison group. During the fourth year of the evaluation, STRIDES’ cost per client was $11,035 compared to $25,682 in the control group and, over four years, STRIDES saved more than $2.3 million.

District of Columbia

Green Door

Harriet Walker faced adversity early in life, losing both her parents and her only brother by her 18th birthday. She persevered, but suffered from post-partum depression after the birth of her first child, Ashley. Following her marriage and the birth of a second child, Harriet was living, in her words “the American Dream.” But when she was laid off from her job, the depression and paranoia returned, and she was admitted to the psychiatric unit of a nearby hospital. She was able to manage her depression with medication, but when she and her husband divorced and her hours at work were reduced, causing her to lose health insurance, she could no longer afford her medication. She was evicted from her apartment, forced to send her children to live with her ex-husband, and, after living in a homeless shelter, Harriet says she had “a nervous breakdown.”

Harriet spent six months in a psychiatric hospital, and, following discharge, she was placed in transitional housing and referred to Green Door, a community-based mental health center that provides a full range of services to help clients develop treatment plans and establish and reach goals. For example, Green Door’s psychiatric services and support staff work with clients to develop an initial recovery plan, connecting them with a community support worker who help clients achieve goals such as finding housing, employment, medical care, or learning about money management. Green Door also operates an intensive, goals-driven day program which helps participants focus on how to take the next steps toward the life they want to live. Finally, because psychiatric illness often affects education levels, Green Door supports clients in pursuing educational goals, ranging from basic reading or math skills to achieving a GED, high school diploma, college degree, or other certification. Harriet worked with Green Door’s employment services to enhance her work skills, and she eventually joined Green Door as a peer counselor on the supported employment staff.

Florida

The state of Florida funds 31 assertive community treatment (ACT) teams which offer housing, medication, and flexible funding to participants. The state establishes guidelines for referral and requirements for assignment to an ACT team. Florida has also adapted the ACT model for children, a program known as the Community Action Team (CAT), which serves youth ages 11-21, though children younger than 11 may qualify under stricter criteria. The primary goal of the CAT program is to keep children in their homes. Analysis found that the average cost of a mental health residential treatment episode is more than $73,000, while the average cost of CAT treatment is $11,250. An evaluation of the first three months of the state’s CAT program found that 94% of children referred to the program were diverted from out-of-home placements and 84% of children improved their level of functioning (as measured by the Child Functional Rating Scale). One provider of CAT services, the Child Guidance Center in Jacksonville, launched its program on August 1, 2013, serving children in crisis, many of whom had not had success in traditional behavioral health treatment, and all of whom were in danger of institutionalization.

Illinois

Thresholds

Thresholds is a recovery services provider, serving approximately 7,100 people with mental illness in Illinois each year. Thresholds focuses on individuals diagnosed with severe and persistent mental illness, but also serves target populations, such as youth, young mothers, and veterans, providing services such as housing and residential programs, supported employment, integrated health care, supported employment, and assertive community treatment. Thresholds’ health care home pilot project, which focused on individuals with the highest use of inpatient psychiatric and ER services reported a 62% reduction in inpatient psychiatric costs.

Iowa

University of Iowa

Iowa’s first assertive community treatment (ACT) team was assembled by the University of Iowa in 1996. Now, there are 5 ACT teams in operation across the state, and their work is supported and coordinated by a technical assistance center at the University of Iowa. Iowa’s ACT teams have achieved some remarkable outcomes, including an 80% reduction in hospitals days, 80% reduction in jail time, 75% reduction in homeless days, and ACT participants are 2.5 times more likely to be employed than non-participants. However, the need for ACT services far outpaces the existing teams’ capacity—ACT is available to less than 25% of Iowans who need it. Analysis by the technical assistance center has found that development of additional ACT teams is thwarted by lack of start-up funds, workforce shortages, and the state’s tradition of decentralized mental health care management.

Louisiana

NHS Human Services

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, thousands of Louisianans with mental illness lost their homes and their source of behavioral health care. Around this time, NHS Human Services began offering assertive community treatment (ACT) and forensic assertive community treatment (FACT) in several Louisiana communities. In 2010, the FACT program in New Orleans achieved a 53% reduction in hospitalizations, representing nearly $1.5 million in health care savings. Iris says that because of the ACT team, she has housing and is working toward her GED. Darrell reports that after Katrina, he was hospitalized in Texas and again when he returned home to Louisiana. But, since becoming an ACT client, he hasn’t been in the hospital and is working full-time. Milan, who was diagnosed with a mental illness in college, says the FACT team helped her “set goals and stay focused.” She is back in school and hasn’t been hospitalized since joining FACT.

Minnesota

Ramsey County

Before he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, Kris O’Leary had a strong work history. Now, he can’t get past the interview stage. Kris is a patient with the Ramsey County Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) team, and he’s been working with Yer Lee, a social worker and vocational specialist, on trying to find a job. Kris is able to interview for positions because, he says, working with the ACT team brought some stability to his life. At the onset of his symptoms, Kris experienced auditory hallucinations; he thought he was possessed and that his house was haunted. The ACT team helped him find medications with side effects he can handle, and he now lives in his own apartment and manages his own bank account. Kris is committed to find a job so he can save money for a car and go to college.

Missouri

Places for People

In 2008, the State of Missouri establish assertive community treatment (ACT) teams in St. Louis, Kansas City, Springfield, and St. Joseph using a combination of state and federal funds, as well as local resources. The program focuses on individuals who are hard-to-reach and hard-to-treat and “the most challenging in our system.” ACT services are provided by agencies located around the state, such as Places for People, which has been involved in the state’s ACT program since its inceptive and currently offers four ACT teams, including one that focuses on individuals transitioning from the criminal justice system. Places for People’s outreach team works to connect with individuals who are homeless and living with mental illness, visiting sites where homeless people gather, engaging those who may display signs of mental illness, and respectfully offering assessment and services. If ACT-level care is appropriate, individuals are assigned to a team that includes a psychiatrist, nurse, vocational specialist, occupational therapist, substance abuse specialist, a peer specialist, and community support workers. This team provides 24/7 access to care.

Places for People’s outreach team encountered Michael at a St. Louis hospital in October 2013, after he had been living in a St. Louis homeless encampment for nine months. Michael moved to the camp from his hometown of Sikeston in order to receive medical treatments in St. Louis, because Medicaid stopped covering his transportation expenses. Michael’s ACT team connected him to resources, including a MetroLink ID that allowed his to travel to downtown St. Louis for food and to medical and recovery-related appointments. Eventually, Michael was ready to change his housing situation, and Places for People connected him with a social services agency who provided him an apartment. Stable housing allowed Michael to receive some necessary medical treatments that his physicians were reluctant to provide because they left him depleted of energy, a status more dangerous for a homeless person. With his housing secure, Michael will begin working with his ACT team’s vocational specialist to explore employment opportunities.

Nebraska

Heartland Family Service

After witnessing his baby sister’s death while he was still a child, Mitch had a series of setbacks—being discharged from the Army just before basic training due to a shoulder dislocation, losing his career as a carpenter due to injury—that led to depression, alcoholism, and homelessness. While he was hospitalized, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia and given medication, which helped, but Mitch wasn’t “stable” until he was referred to Heartland Family Service’s assertive community treatment team. The team helps Mitch adhere to his treatment plan, including taking his medication as prescribed, and exercise and nutrition staff accompany him on weekly walks to help Mitch stay healthy and ease some of the side effects of his medication. Mitch is now living with his brother, and admits that his progress has been a hard struggle, “but I won’t give up.”

North Carolina

Carolinas HealthCare System

Jessica duCille, who suffers from schizoaffective disorder (a type of schizophrenia that also includes manic and depressive episodes), had been hospitalized dozens of times in facilities across North Carolina. During her final hospitalizations, Jessica was referred to an assertive community treatment (ACT) program operated by Carolinas HealthCare System. ACT team members provide 24/7 support to patients and stabilize the patient by addressing their immediate needs first—housing, food, clothing—before turning to the mental health care needs that are often unmet. Through the ACT program, Jessica works with a therapist and a physician and participates in art therapy. She and her 3-year-old daughter moved into their own apartment, Jessica is looking for a job, and she hasn’t been back to the hospital since she joined ACT. Jessica’s participation in this ACT program costs about $1,700 per month, an investment that pales in comparison to the $20,000 cost of just an average-length eight-day inpatient psychiatric admission. On average, 64% of people with schizophrenia are readmitted within one year, but Carolinas HealthCare System’s ACT program has lowered that rate to 4%.

Ohio

State of Ohio and Franklin County Alcohol, Drug, and Mental Health Board

The State of Ohio, through the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, funded the creation of the assertive community treatment (ACT) coordinating center of excellence to provide technical assistance to organizations that offer ACT as well as organizations that integrate ACT with integrated dual disorder treatment (IDDT), an evidence-based practice for individual with co-occurring several mental illness and substance use disorders. Building on work funded by The Health Foundation of Greater Cincinnati, this center of excellence aims to increase the number of organizations in the state offering ACT. To that end, in September 2014, the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services selected the Alcohol, Drug and Mental Health Board of Franklin County to expand ACT and IDDT for homeless individuals with untreated mental health and substance use disorders, under a federal grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The Board’s evaluation of ongoing ACT-IDDT work resulted in significant savings to the county through reduced psychiatric hospitalizations, and lower use of crisis and residential services.

Oklahoma

Assertive community treatment (ACT) teams in Oklahoma successfully reduced the need for inpatient care and incarceration by focusing enrollment outreach on individuals with significant hospitalizations or those entering or leaving the criminal justice system. Utilizing a variety of funding sources (including state appropriations, Medicaid billing, redirection of existing resources at a state-operated community mental health center, a federal grant, and a state Medicaid revenue source), the ACT teams focused their work on increasing medication compliance, securing employment, keeping families together, and assisting with basic needs, such as housing, among other tools. As of April 2006, 14 ACT teams in Oklahoma were serving 575 people with serious mental illness, with the capacity to serve as many as 950 individuals. In comparing data from the year prior to ACT enrollment for 124 individuals with any hospitalization with data from the year following ACT enrollment:

- The number of inpatient days fell from 5,233 to 1,942, a 63% reduction.

- The number of individuals hospitalized also fell by 53%.

- Total number of jail days decreased from 1,050 to 315, a 70% reduction.

Pennsylvania

Philadelphia Mental Health Care Corporation

The Philadelphia Mental Health Care Corporation (PMHCC) was formed in 1987 by the City of Philadelphia in order to implement a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Program for Chronic Mental Illness. Shortly after its creation, PMHCC developed the Philadelphia Community Treatment Teams Incorporated to serve patients discharged from the Philadelphia State Hospital when it was closed. The community treatment teams now serve a broader range of patients, with capacity to assist 850 individuals with severe mental illness as well as co-occurring disorders, such as substance use disorders or development disabilities, through Assertive Community Treatment or Blended Enhanced Case Management, another community-based treatment model. Under each model, clients have 24/7 access to a member of their care team, which uses an holistic approach to service provision, ensuring all of each client’s needs are considered, including housing, all types of health care, vocational and education opportunities, financial resources, recreational opportunities, and more.

Texas

Metrocare Services

Jim had four hospitalizations related to his schizophrenia diagnosis with a year, which led to a referral to Metrocare Services’ assertive community treatment (ACT) team. Following his last hospital discharge, the ACT team worked to help Jim find housing and reestablish his Social Security benefits. The team helped Jim learn to use the city bus, establish and keep a budget, develop social skills, and take his medication on time. One critical element of the ACT team’s work is helping Jim recognize symptoms of his schizophrenia, so that he can reach out for support before the situation becomes dire. Though Jim did have some relapses during his first eight months with the ACT team, he was able to ask for help and required a less intense level of care than he previously might have. After eight months with ACT, Jim was transferred to an outpatient clinic for ongoing services.

Washington

King County

King County has adopted the assertive community treatment model to the criminal justice population through a program called forensic assertive community treatment. In a separate project in Washington State, King County is adopting the ACT program to the criminal justice population through a program called forensic assertive community treatment (FACT). Through a focus on individuals with extensive criminal histories and a history of homelessness or who are at risk of becoming homeless, King County’s FACT program aims to reduce use of the criminal justice system and of inpatient psychiatric services while improving housing stability and community tenure. The evaluation of King County’s FACT program is particularly strong because individuals were randomly assigned to either participate in FACT or to receive services as usual. FACT participants experienced statistically significant reductions in jail and prison bookings and jail days—45% and 38%, respectively.

Washington State

In an effort to reduce use of two state psychiatric hospitals, Washington launched a statewide network of ten assertive community treatment teams in 2007. Demonstrating the model’s flexibility in accommodating local needs, these teams were also trained in person-centered and recovery-oriented services. The teams were able to achieve a reduction in length of stay at the state’s two psychiatric hospitals of approximately 32 days per person per year, and spending on patients with the highest state hospital use before the start of assertive community treatment was reduced by between $16,719-19,872 per person per year.

West Virginia

West Virginia University Chestnut Ridge Center

West Virginia’s Medicaid program reimburses providers assertive community treatment (ACT) services, but limits enrollee eligibility to those who meet specific criteria related to high utilization of psychiatric services. Individuals may also quality if they have severe and persistent mental illness and are homeless, have frequent contact with law enforcement or the criminal justice system, or are dually diagnosed with a substance use disorder. Limiting eligibility in this way allows West Virginia to focus behavioral health care dollars on individuals who will truly benefit from ACT. West Virginia University’s Chestnut Ridge Center operates one of the states ACT teams, providing 24/7 services by a team of professionals within the community where members live. The team and patient together develop a treatment plan and establish goals that will help the individual attain or remain in the living situation of their choice.

Wisconsin

Mendota Mental Health Institute

The assertive community treatment (ACT) was born at the Mendota Mental Health Institute, a psychiatric hospital operated by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services in Madison. A three-person team, Dr. Arnold Marx, Dr. Leonard Stein, and Dr. Mary Ann Test, saw that the progress patients made while in the hospital was often lost when the patients were discharged into the community. The team wanted to test their theory that the 24/7 care patients received in the hospital was crucial to alleviating symptoms and like even more important when patients moved back to the community. In 1972, these three researchers moved hospital staff out into the community to care for recently discharged patients, and the ACT model of care was born. Its purpose is to reduce or eliminate debilitating symptoms of mental illness and acute episodes or recurrences. This requires ensuring patients have the necessities of life as well as treatment so they can ultimately live independently and lead a productive life. Today, the Mendota ACT program provides 130 patients with a broad array of services, such as prescription acquisition and medication management, psychotherapy, vocational and educational services, activities of daily living and house assessment and support, family counseling, and much more.