Memo Published October 11, 2013 · Updated October 11, 2013 · 5 minute read

Are Short-Term U.S. Debt Markets Flashing an Early Default Warning?

Lauren Oppenheimer & John Vahey

In the past week, yields on very short-term U.S. debt increased sharply—a flashing red light indicating some default fear in the market.

This rise in rates meant that investors in very short-term U.S. Treasury debt began to harbor some measurable level of doubt about the willingness of the United States Treasury to fulfill its financial obligations over the next month. These rising rates showed that among market participants, the possibility of breaching the debt ceiling increased the risk of holding short-term Treasury debt.

In a sign of the extreme sense of caution in the markets, Fidelity Investments—the largest U.S. money market mutual fund—reportedly liquidated all of their short-term T-bills.1

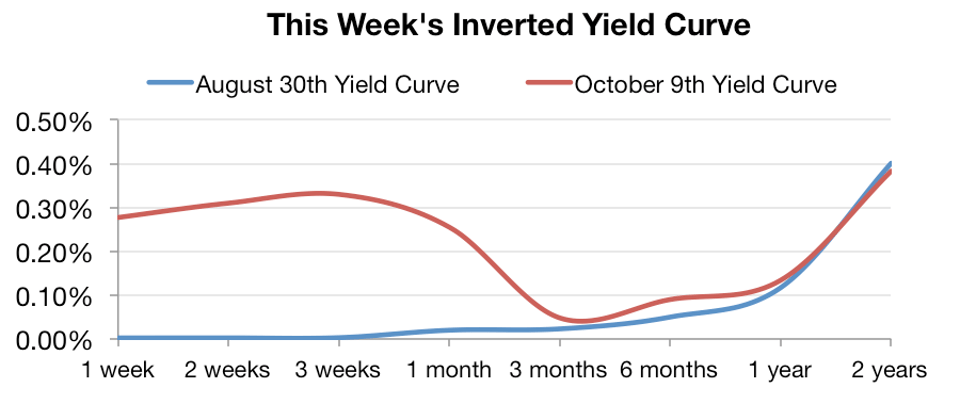

This fear created a market anomaly—an inverted short-term yield curve. Yields on one-month U.S. debt shot higher than yields on one-year U.S. debt. This is exactly the opposite of normal market conditions when longer-term debt carries higher yields than short-term debt.

This market anomaly, some believe, is another alarming sign that investors are considering that the unthinkable—a U.S. debt default—is possible.

How to spot the default fear in the debt markets.

Last week, the yields of U.S. T-bills maturing around the October 17th deadline “blew out”—that is market-speak for rose sharply. T-bills are essentially Treasury bonds with short maturities, no more than one year. These rising bond yields signaled increased risk in the bond market.

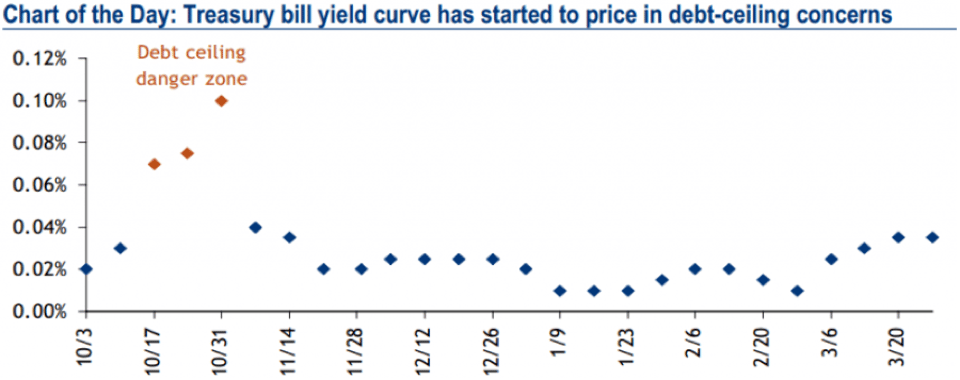

A chart prepared by Bank of America Merrill Lynch last week, showed short-term Treasury bills trading at sharply higher yields than debt that matures well after the supposed default risk zone—an indication of default fear in the market.

BofA Global Research, Bloomberg, Business Insider

The market perception was that the riskiest T-bill to own was the bill that matures on Halloween, October 31st. Two weeks ago, owners of this T-bill accepted a puny .03% yield. But market sentiment changed dramatically. Earlier this week, investors demanded .33% to hold this debt—a 30 basis point increase in one week.

What happened in the T-bill market this week?

This week, the yields on the T-Bills maturing 10/17/13, 10/24/13, 10/31/13, 11/07/13, 11/14/13—dates within the default risk zone—continued to rise.

- T-bill maturing 10/17/13 yielded .2775% up from .0025% on 9/30/13

- T-bill maturing 10/24/13 yielded .31% up from .0025% on 9/30/13

- T-bill maturing 10/31/13 yielded .33% up from .03% on 9/30/13

- T-bill maturing 11/07/13 yielded .255% up from .0175% on 9/30/13

- T-bill maturing 11/14/13 yielded .33% up from .0175% on 9/30/13

For each T-bill, there is a significant jump from the end of last month.

An inverted yield curve

The dramatic shift in the markets was best displayed by this week’s oddly shaped yield curve. The yield curve plots the yields of U.S. debt based on when the debt matures.

The chart below shows that the debt maturing during the default risk zone—in the next three weeks—was trading at sharply higher yields than just a little over a month ago—when the curve was normal.

Investors were saying, “Sure, I will own debt that matures in the next few weeks, but only if I am paid additional yield for the additional risk.”

Data from Bloomberg, 10/9/13

This is significant because normally Treasury debt that matures within a few weeks is viewed as extremely safe. It is safer to lend money for one week than to lend money for one year. So a big, alarming shift in sentiment took place in the portion of the market that is normally viewed as extremely safe.

So far, these fears have been contained to very short-term Treasury debt. But, many investors see this shift as the “canary in the coal mine.” They fear if default occurs, these increased rates could spread to the longer-term five-year, 10-year, and 30-year debt. This would send borrowing costs on U.S. corporate debt and mortgage debt higher—economic growth would be slowed.

Who owns T-bills? How will they be harmed if the U.S. defaults?

T-bills are as safe as cash—normally. Investors in T-bills, like corporate treasurers and money market mutual funds, receive a tiny return on investment and are assured to get their money back in weeks or months.

Many businesses use T-bills to manage their cash. If payroll is due at the end of the month, a corporate treasurer may continually invest cash in T-bills that mature in a month. When those T-bills mature the company gets cash to meet its payroll obligations (plus a little return on investment). Employees are paid. The company has made a tiny return on their investment. Everyone is happy.

But, what if a T-bill payment is delayed because the statutory debt limit has not been raised? That’s a problem. The business may be unable to meet their own obligations—like paying employees and suppliers on time. While we are not yet at the October 17th deadline and there are many who believe that T-bills would still be honored if the ceiling is breached, this increased risk was displayed by this week’s higher yields.

The fact that these specific short-term T-bills became the “black sheep” of the credit markets is significant. Investors shunned them because of the risk that the government won’t pay them what they are owed on time.

Conclusion

Normally, investors will accept tiny yields to hold short-term debt. In most cases, the yield on one-year debt is higher than the yield on one-week debt. But this week, market yields flipped. The risk premium on very short-term debt shot up and over the yield on one-year debt.

This risk premium signified that the market was not confident in the willingness of the United States to honor its financial obligations—not a good thing for our country or our economy.