Memo Published January 11, 2024 · 11 minute read

Employment and Earnings Outcomes Shape Graduate Students’ Perceptions of Program Value

Chazz Robinson

Takeaways

- Students expect (but don’t always get) employment and earnings boosts from attending a graduate program.

- Students think graduate school was worth it—if they get a job.

- Graduate degrees are not a surefire ticket to financial security.

Prospective graduate students must weigh potential benefits against the time, money, and additional debt it takes to pursue education beyond a bachelor’s degree. With growing federal attention on graduate education and nearly half of the national student loan portfolio held by this population, it is imperative to understand the experiences of graduate students to ensure informed policy development and implementation.

To learn more about students’ perceptions of their graduate education, we partnered with Global Strategy Group to poll 1,000 current and former graduate students about their program experiences and post-graduation outcomes. We also conducted focus groups to explore the individual experiences of current and recent graduate students. Woven into the findings is the impact that employment status and earnings after graduation have on how they perceive the value of their graduate education. Students both want and expect to get a good job and earn more after graduate school, but that doesn’t always match with reality, and that friction plays a key role in graduate students' perceptions of program value.

Students Expect (But Don’t Always Get) Employment and Earnings Boosts from Attending a Graduate Program

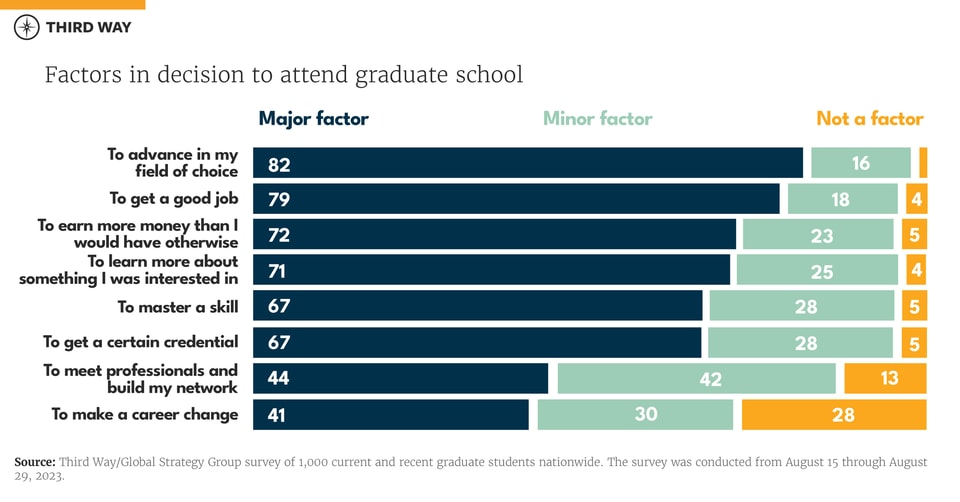

Students’ decisions about enrolling in a graduate program are primarily guided by their future employment opportunities and earning potential. Advancing in their field of choice (98%), getting a good job (97%), and earning more money than they would without an advanced degree (95%) had the largest total factor percentage scores and greatly influenced respondents’ decision to attend graduate school.

In focus groups, prospective graduate students expressed that they viewed grad school as an investment and were willing to make significant trade-offs on costs, mental health, and time in the workforce to pursue advanced degrees for the perceived benefits they would obtain post-graduation. In the short term, students expect a good experience, to gain new skills and needed credentials, and to make their families proud. In the long term, graduate students expect payoffs primarily tied to their employment and earnings outcomes, such as career advancement. These findings reveal that, like undergraduates, the primary reason graduate students are enrolling in advanced degree programs is to see career and income gains. Even when graduate students expect less quantifiable short-term benefits, their long-term goals are tied to employment and earnings. This was exemplified when current and recent graduate students were asked to speak about their motivation for pursuing or completing an advanced degree:

“I just wanted to be more competitive in the job market because I felt like as I was looking for jobs, I wasn't finding something that was exactly what I wanted, and also the pay is not enough. And I was like, I need to have more degrees apparently.”

“I know…in social work, I mean, you really can't get any decent jobs without a master's degree. So I was kinda forced to go back.”

“As far as money, [it was] maybe not so much of the money you would end up owing to go to grad school that I really thought about before making the decision. I was more dependent on the money I would make thereafter. That was more of a money factor.”

“Had you told us that you’ll go to school and come out making the same in five or ten years, I don't think anyone would have done that. So, I think you feel the money is there. Once you realize the money is there, that's one thing you can put to rest. But money always isn't the only reason. It's not the only motivator, but it's gonna be there in the end.”

"If I'm paying you X amount of money or agreeing to be in debt for X amount of money, to achieve said degree and excel in that career path, then that's exactly what I should achieve."

Whether it’s career advancement, increased earnings, or job prospects, graduate students clearly identify upward economic mobility as crucial when choosing a program—even students with other motivations for attending graduate school state that long-term employment matters. When choosing a program, these students expect an economic boost, but the return on their educational investments is not always guaranteed.

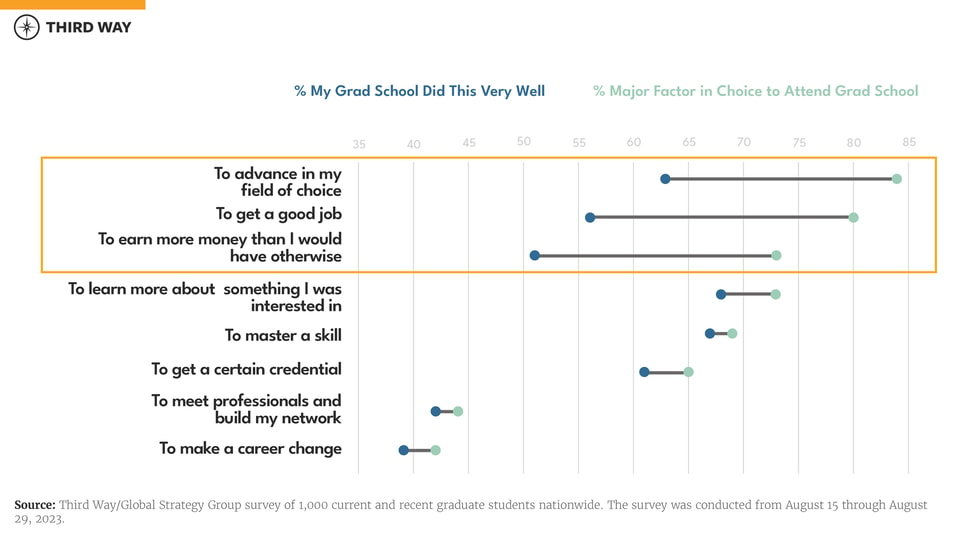

Survey responses indicated that large gaps exist between what students expect from their graduate programs versus what they feel their schools delivered. When asked how well their school delivered on meeting the major factors they identified for deciding to attend graduate school, recent grads believed their school fell short on all but two. And the top three factors they identified for attending grad school in the first place—advancing in their field of choice, getting a good job, and earning more money—showed the largest gaps between what they hoped to get out of grad school and what their school actually delivered for them.

Less than 60% of recent grad respondents felt their grad school did “very well” in helping them get a good job (a 23 percentage-point drop from what they had hoped) or earn more money than they would have otherwise (a 21 percentage-point drop). The satisfaction gap between what students expected before enrolling versus what they believed post-graduation from the programs is alarming given that graduate students are making major trade-offs to enroll in programs with distinct career goals in mind.

Students Think Graduate School Was Worth It—If They Get a Job

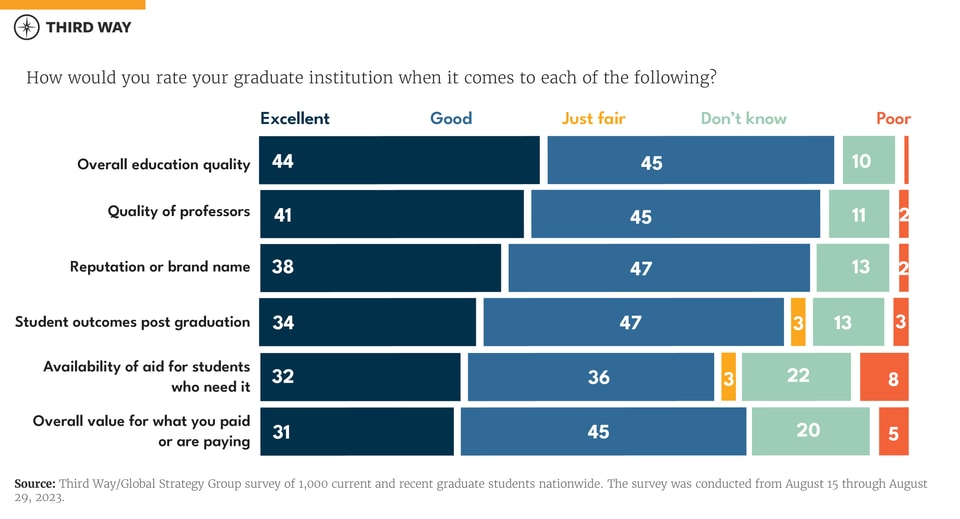

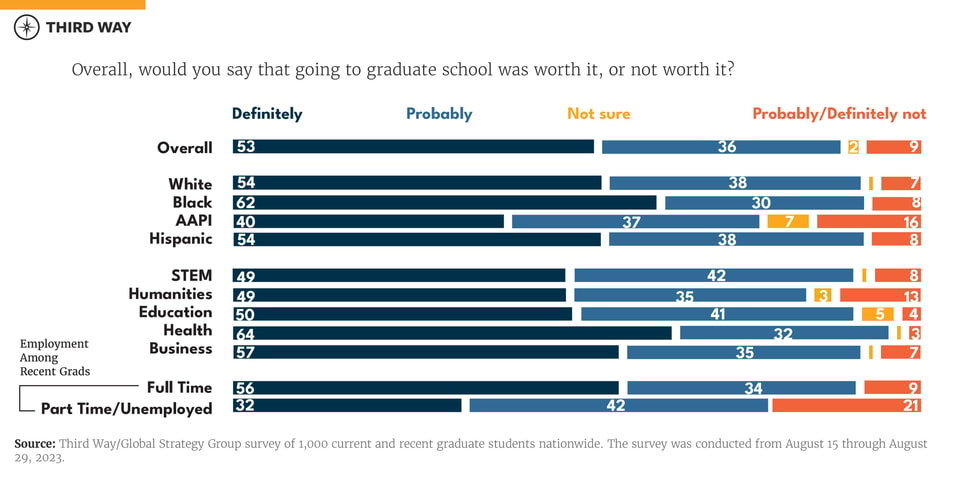

Employment is a mediating factor in how graduate students perceive the value of their graduate program. Graduate students give their institutions a high mark for quality, with 89% rating their overall educational quality as “excellent” or “good.” Even with high marks of overall quality for their programs, there were considerable differences in how graduate students responded when asked if their education was worth it correlated with their race, program field, and employment.

Racial breakdowns show that 62% of Black students, 54% of white and Hispanic students, and 40% of Asian American and Pacific Islander students feel that their graduate education was “definitely worth it.” There is a considerable difference in how different racial groups view their educational experiences, and this highlights a need for further analysis to uncover why these differences exist.

Exploring degree fields reveals that graduate students in health programs felt most strongly that their graduate education was worth it (64%). In comparison, fewer than half of non-health STEM and humanities students (49%) felt certain their degree was worth it. These data highlight that the field a student enters can have a meaningful correlation with whether students feel their degrees are valuable.

Notably, graduate students' perceptions of their program value are influenced by their employment status. Recent graduates have more positive perceptions of the value of their degree if they are employed: 56% of recent graduates who are employed full-time said their graduate schooling was definitely worth it, compared to 9% who did not. Results were more mixed among recent graduates who are working part-time or unemployed, with 32% saying graduate school was definitely worth it versus 21% who said it was not.

We dug deeper into graduate students’ perceptions of program value in focus groups, asking them to explain whether graduate school was worth it. Their responses highlight the impact employment has on their perception of value:

“It just depends on the day, I think… the job market is just not what I would like it to be, but careers that I want, you need a doctorate for.”

“My professors were like, oh yeah, it's gonna be easy to get a job when you have your master’s. And maybe it was at that point in time in the job market, but I'm just finding that, like, you know, I've been done with school for like a year now. And it's just I'm like, where are the jobs?”

“I assumed that getting the master’s would make it easier for me to find a job. I've been job searching these last few months and I've been getting a lot of no’s…But I just kind of assumed that for positions that I'm applying for that only require the bachelor's, I have a leg up compared to those with only the bachelor's, but I'm still getting kind of the same response. So it's not as much of a differentiator as I thought it would be.”

“Not [worth it] yet. I just got a new job that I started six weeks ago and before that, the job I was in, I would have said it wasn't worth it just because it was such a low-paying job.”

Graduate students who feel their schooling was worth it see a direct connection between their degree and employment, while those who don’t feel it was worth it say that their degrees did not lead to jobs they were happy with. Getting graduate students employed at face value seems like the easy solution, but a deeper dive reveals that’s only solving one part of the problem.

Graduate Degrees Are Not a Surefire Ticket to Financial Security

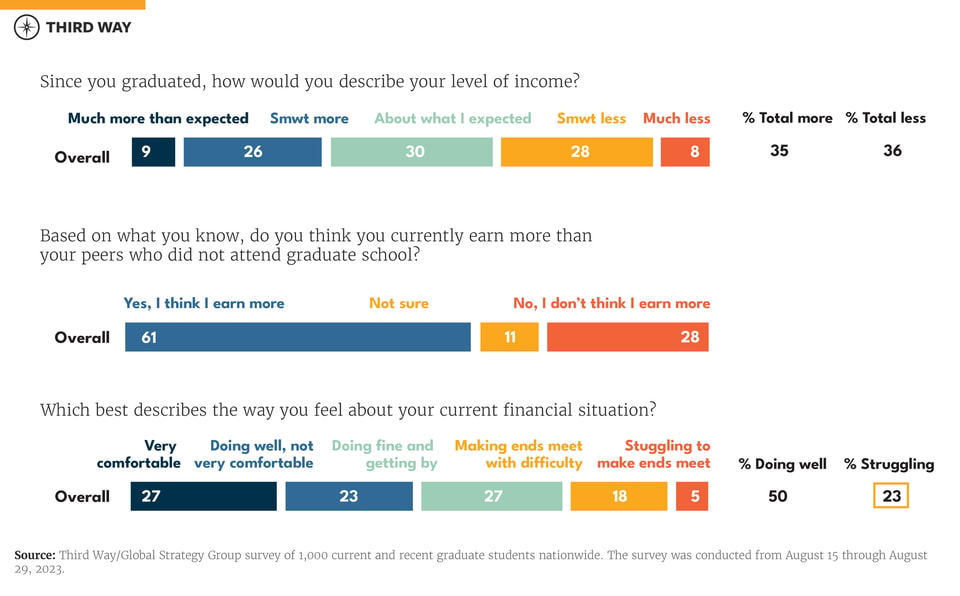

Graduate students expect earnings gains post-graduation, but results show that an economic boost isn’t a guarantee. A plurality of respondents (30%) report earning about what they expected, but there is an even split between those making more (35%) or less (36%) than expected. Others are unaware if their program provided their desired earnings boost, with 39% saying they were unsure or didn’t think they made more than their less-credentialed peers. At the same time, nearly a quarter of graduate students indicated they were struggling to make ends meet when asked about their current financial situation.

To further investigate whether graduate students received earnings boosts from their graduate programs, we analyzed 4,869 in-person master’s programs with available data in the College Scorecard. Polling data revealed that many graduate students are unsure if they make less than their less-credentialed peers, so we compared the earnings of master’s-degree graduates (four years after graduating) to the median earnings of high school and bachelor’s degree completers within their institution’s state to find out.

Our results confirm that at the master’s degree level, not all graduate students fare well economically after graduation compared to their less-credentialed peers. A whopping 2,106 master’s programs don’t leave graduates able to out earn someone with a bachelor’s degree within their state, while 88 master’s programs leave graduates earning less than a high school graduate. Poor financial outcomes after a huge investment in graduate school can be devastating. These findings highlight that graduate students are not guaranteed an economic bump post-graduation despite expecting that they will receive one.

A whopping 2,106 master’s programs don’t leave graduates able to out earn someone with a bachelor’s degree within their state, while 88 master’s programs leave graduates earning less than a

high school graduate

Conclusion

This public opinion research makes it clear that graduate students expect an economic return on their educational investments, but that isn’t always what they receive post-graduation. This problem warps students' view of how much they value their graduate education and the quality of their livelihood . On the federal level, when graduate borrowers struggle financially, it drastically impacts their repayment ability and the total amount the government recoups, creating a system that takes harmful risks with taxpayer dollars and students’ financial futures. Federal policymakers should know that employment and earnings gains are not guaranteed with a graduate degree but are of utmost importance to graduate students as they work to fill in information gaps about graduate students and consider policy options to address these problems.1

Methodology

Global Strategy Group surveyed 1,000 current and recent graduate students who are registered voters nationwide. The survey was conducted from August 15 through August 29, 2023. The precision of online surveys is measured using a credibility interval; in this case, the interval at the 95% confidence level is +/- 3.1%.

To view the topline results, click here.

To examine master’s degree outcomes, we used the most recent College Scorecard release from April 2023 (which reflects master’s program-level data from the 2020-2021 academic year) and the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2021 five-year estimates).

Using available data, we focused on the median earnings of graduates with a master’s degree (four years after attending) in each program and the median earnings of a high school diploma or bachelor’s degree holder in the state. We limited our analysis to in-person master’s programs to capture students who are most likely to be living and working within the state of the institution at which they attended graduate school. Programs that were not in person or didn’t have data were excluded from this analysis.

We calculated the earnings premium of each program using this formula: