Memo Published June 20, 2017 · Updated June 20, 2017 · 10 minute read

Preserve the Reserve: Why the Pell ‘Surplus’ Isn’t Expendable

Tamara Hiler

From a young age, many of us are taught that a cornerstone of smart financial planning is to “save for a rainy day.” Because life is unpredictable—from mechanical problems and unanticipated bills to natural disasters and medical emergencies—having the foresight to build a store of funds in financially stable times can alleviate long-term pain when unexpected costs arise or pecuniary fortunes change.

This concept of creating a “rainy day fund” is not unique to managing personal finances, but is also an important budgeting tool used by policymakers in order to “smooth out the ebbs and flows of unpredictable economic cycles.”1 One federal program with this type of safeguard is the Pell Grant program, which provides need-based financial assistance to millions of low- and moderate-income students attending college each year. Because the federal government cannot accurately predict how many Pell Grants will be disbursed on an annual basis (due to changes in college enrollment or the number of students meeting the program’s income eligibility requirements), having a rainy day fund available helps to prevent the interruption of student aid in years where the number and need of students accessing the program exceeds the amount of funds initially budgeted.

Though this hasn’t always been the case, today the Pell Grant program is in good financial health, with its reserve currently holding a balance of $10.6 billion to help guarantee the program’s long-term stability.2 While the Trump Administration has followed Congress’ lead and reinstated the year-round Pell program, it’s latest budget proposal would still cut close to $4 billion from the program’s rainy day fund in order to finance other administrative priorities—many of which fall outside the scope of education altogether.3 But with the average Pell Grant award totaling around $3,700, a cut of this size would result in more than 1,000,000 fewer Pell Grant awards available for low- and moderate-income students. As a result, using money from the Pell reserve to pay for other priorities will have long-term implications for the millions of low- and moderate-income students who rely on Pell Grant awards to access and complete college each year. This memo offers a brief explanation of why Congress should resist the temptation to dip into the current Pell reserve.

What is a Pell Grant?

For more than 40 years, the Pell Grant program has been recognized by lawmakers on both sides of the aisle as one the most important ways the federal government can help low- and moderate-income students access and pay for higher education. Last year alone, 7.6 million students—or one-third of the entire undergraduate population—received an average award of $3,724 to attend a variety of certificate-granting, two-year, and four-year institutions.4 Today, Pell Grant recipients are eligible to receive these need-based grants (which, unlike loans, don’t have to be paid back) for a total of 12 full-time semesters.5 More than three-quarters of all Pell recipients come from families earning annual incomes of $40,000 or less, highlighting just how critical this program is in helping all students unlock the doors to postsecondary success.6

How do Pell Grants help students succeed?

In addition to providing access to the promise of postsecondary education for millions of students each year, research has shown that need-based grant aid can also increase the likelihood of low- and moderate-income students enrolling in and completing college.7 Providing this type of support is critical given that earning a college degree is one of the surest tickets to securing a middle-class life. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that college graduates earn close to a million dollars more over the course of a lifetime and face unemployment rates significantly lower than their non-college completing peers.8 And boosting completion rates is more important than ever, especially because students who start but don’t complete are worse off since they often end up with debt but no degree to help them pay it back.9

How is the Pell Grant program funded?

Given the importance of this financial lifeline, it is no surprise that approximately 30% of annual appropriations for the Department of Education go directly towards financing the Pell Grant program.10 This is in large part because the majority of the program’s funding comes through the discretionary budget, with Congress establishing a maximum base award for Pell in its annual appropriations bill. A small “add-on” award is also provided on the mandatory funding side and is combined with the base discretionary amount to create a total maximum award that Pell-eligible students can receive in any given year (last year, that total amount was set at $5,920).11 Because the bulk of Pell Grant funding happens through the annual appropriations process, Congress must predict months in advance the number and amount of Pell Grants that will be used in the coming fiscal year. This can be difficult given that the number and amount of Pell Grants awarded can shift drastically if there are unexpected fluctuations in college enrollment or the economy.

What happens if the program gets more applications than it has money to fund in a certain year?

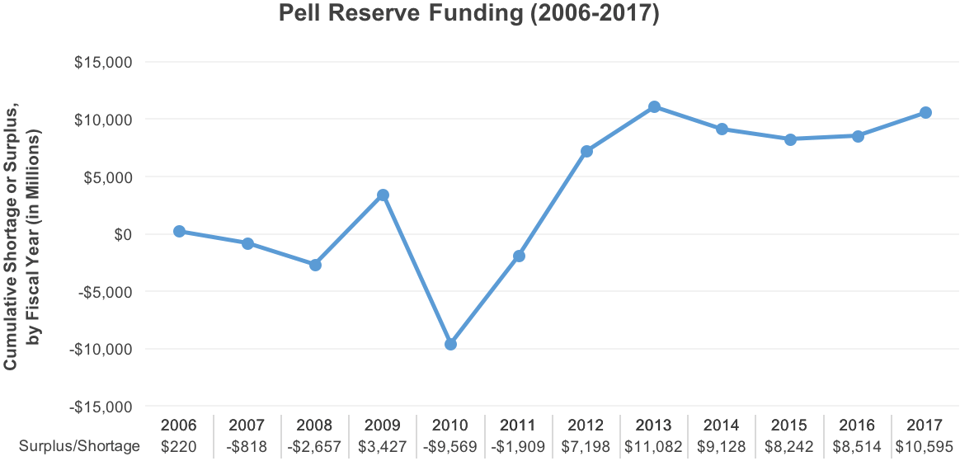

A mismatch in funding can occur if Congress’ predictions of anticipated cost falls above or below the total amount of money needed for Pell Grants in a given year. This means Congress can end up with a shortfall of funds if the number and need of students accessing the program exceeds the amount of money initially budgeted. To fill this funding hole, lawmakers must either quickly act to increase Pell’s appropriations (an option that is all but off the table in today’s fiscal and political environment) or make cuts to the awards. Conversely, a surplus of funding can occur if costs for the program end up lower than originally projected (i.e. fewer students access Pell in a given year). The excess funding is held in a “Pell reserve”—or rainy day fund—that can be used to help the program weather future dips when a shortfall happens again. As the graph below depicts, such funding ebbs and flows have occurred frequently over the last ten years, with Pell’s reserve swinging from a $10 billion shortfall in 2010 following the Great Recession to the $10.6 billion in reserve funding that exists today.

Source: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/recurringdata/51304-2017-01-pellgrant.pdf

The most dramatic of these funding fluctuations occurred at the height of the Great Recession. Pell Grant usage surged due to a greater number of students turning to higher education in lieu of navigating the job market in a weakened economy. And at the same time, more students found themselves with lower incomes that allowed them to qualify for additional financial aid.12 Because Pell Grants are guaranteed to any student who meets predetermined income thresholds and eligibility requirements, Congress had no choice but to fund this increased spike in awards.

As a result, the Pell Grant Program fell into a $10 billion funding hole, a scenario that in most circumstances would have had made the program impossible to sustain had it not been for massive investments poured into the program through both the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and the Student Aid and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2010.13

How did we build the reserve we have today?

Though Congress was able to find additional funding to rescue Pell without severely cutting its benefits to students in the aftermath of the Great Recession, we can’t count on a similar outcome if the country were to face an extreme economic downturn again. That experience made Congress acutely aware of the need to create a backup source of funding that would allow the program to endure unexpected spikes in usage and insulate millions of students from losing access to this critical resource at the times when they needed it the most. That is why following 2010, Congress took painstaking steps to proactively rebuild the program’s reserve and nurse it back to the healthy $10.6 billion it has on-hand today. It did so in part by limiting eligibility requirements so that fewer students qualified for the grants.14

Specifically, Congress chose to eliminate year-round Pell and subsidized loans for graduate students in 2011, as well as shortening the cumulative lifetime eligibility for students from 18 semesters to 12 semesters in 2012—all to offset costs and intentionally build up the existing reserve.15 Those were not easy—but deliberate—steps to dig the Pell program out of a shortfall and ensure it would not have to make further emergency cuts if faced with another unexpected spike in usage. As Marcella Bombardieri and Ben Miller from the Center for American Progress note, “the 2012 budget cuts alone were estimated to make at least 100,000 Pell recipients ineligible for the program” in order to preserve its long-term prosperity.16

It is important to recognize that the funding that exists in the reserve today represents a promise Congress made to students that the benefits of the Pell program would remain intact, despite the vicissitudes of enrollment and economic health from year to year. It was a prescient and fiscally responsible decision to create a reserve of funds dedicated to keeping the Pell program solvent and minimize further cuts or service disruptions to students in the case of uncertain economic times.

How could dipping into the Pell reserve now affect the long-term sustainability of the program?

Recent analyses show that barring any major fluctuations in the economy or changes to the program’s eligibility rules, the current reserve could sustain the Pell program until at least 2025.17 But with more jobs requiring postsecondary degrees in today’s economy, it’s inevitable that the demand for Pell will also continue to rise—not decline—in the years to come.18 This is all the more true now that states have continued to expand the availability of free community college programs—which rely heavily on the Pell Grant in order to succeed. This is because most such programs (like the ones in Tennessee, Oregon, and Nevada just to name a few) rely on a “last-dollar model” that require students to tap into their federal grants first before using state aid.19

As these programs continue to expand, Pell Grant usage will grow, too. Any budget that dips into the reserve now will almost certainly force policymakers to face tough choices about the program’s eligibility rules sooner rather than later in order to keep the program afloat. By preserving the Pell reserve, the federal government can keep its promise to students that if they stay in school and keep progressing towards a credential, they’ll have Pell to help them cross the finish line.

Conclusion

From car problems to unforeseen medical emergencies, many of us have experienced the relief that comes with having a reserve of money on-hand to help us weather life’s unpredictable financial storms. This same principle applies to the Pell Grant program, whose rainy day fund ensures that critical Pell Grant awards will be available to the millions of students who benefit from the program each year. Given the unpredictable nature of the economic circumstances that drive how many students will rely on Pell Grant funding at any given time, preserving money in today’s Pell reserve now can help prevent funding shortages in the future. With the global economy requiring more students to have postsecondary degrees in order to access higher-skilled jobs and earn competitive wages, Congress and the administration should concentrate on expanding—not limiting—this wildly successful and popular tool for helping more students make it to and through college.