Memo Published February 21, 2019 · 17 minute read

Reader’s Guide to Understanding the US Cyber Enforcement Architecture and Budget

Brandon Gaskew

Takeaways

The United States is facing a rising cybercrime wave, affecting every sector of the US economy and threatening America’s national security. Despite this growing threat, there is a serious gap in the US government’s response—our research has found that less than 1% of malicious cyber incidents ever see an arrest of the criminal. This cyber enforcement gap has allowed cybercriminals to operate with impunity and must be addressed in congressional responses to the issue.

Many US government entities have the responsibility of reducing the cyber enforcement gap and Congress must assess whether they have the necessary resources to shrink the gap. To help in these efforts during the Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 budget cycle, Third Way has prepared a Reader’s Guide for Members of Congress and their staff to help them understand the key government entities involved in cyber enforcement and their current funding levels.

While much of the budget levels for key cyber enforcement entities in the US government have remained either flat or, in certain cases, been increased this has little impact on the cyber enforcement gap. Congress should provide additional resources to make more progress in reducing the cyber enforcement gap.

This Reader’s Guide includes three sections:

- An introduction to the US cyber enforcement gap and a proposal to reduce the gap by rebalancing US cybersecurity policy from a heavy focus on network security to a policy that also goes after the human attacker using law enforcement and diplomacy;

- A mapping of the key federal government departments and agencies with a role in cyber enforcement; and

- An overview of current budget levels for cyber enforcement across key government entities where information is publicly available.

The United States is facing a rising cybercrime wave, yet, a tremendous enforcement gap currently exists in government efforts to identify, stop, and punish the human cyber attackers.

The United States and countries around the globe are currently facing a stunning gap in their efforts to bring to justice cybercriminals and other malicious cyber actors. This national security and economic threat continues to rise, while offensive efforts to counter it have fallen short.

A rising and often unseen cybercrime wave is mushrooming in America. There are approximately 300,000 reported malicious cyber incidents reported to the Federal Bureau of Investigation per year hitting every sector of the US economy— which is likely a vast undercount since many victims do not report break-ins to begin with.1 Malicious cyber activity perpetrated by nation-states, criminal networks, terrorist groups, lone actors, and others has cost the US economy anywhere from $57 billion to $109 billion annually and these costs are increasing. Cybercrime tools have been used to attack vital US national security institutions and steal critical information. A single one of these incidents can hit countless victims in many different countries no matter the location of the perpetrators.2

Third Way has launched a new Cyber Enforcement Initiative aimed at identifying policy solutions to boost the governments’ ability to identify, stop, and punish malicious cyber actors.3 Through this Initiative, Third Way has found that, on average, only 3 out of 1,000 of the malicious cyber incidents that occur in the United States annually see an arrest, which is an enforcement rate of less than 1%.4 This cyber enforcement gap is allowing criminals to engage in malicious behavior without any fear of being caught or punished.

Government is the only institution with the authority to pursue the human attacker and bring them to justice. However, in the United States, a heavy focus of cyber policy discussions has been building better cyber defenses against intrusion. To close the cyber enforcement gap, Third Way has argued we must rebalance US cyber policy from a predominant emphasis on network protection to a policy that also uses law enforcement to go after the human cyber attackers and diplomacy to boost international cooperation and capacity in order to do so.

In order to rebalance America’s cyber approach and prioritize law enforcement and diplomacy, the country needs a comprehensive strategy for strengthening the US government’s abilities to identify, stop, and punish cybercriminals and other malicious cyber actors. To help develop such a strategy, Congress must start by first understanding the key government entities involved in cyber enforcement and assess whether their current funding levels meet the challenges they are faced with in reducing the cyber enforcement gap.

There are a multitude of government entities involved in cyber enforcement and Congress must assess whether they have the needed resources to make progress in reducing the cyber enforcement gap.

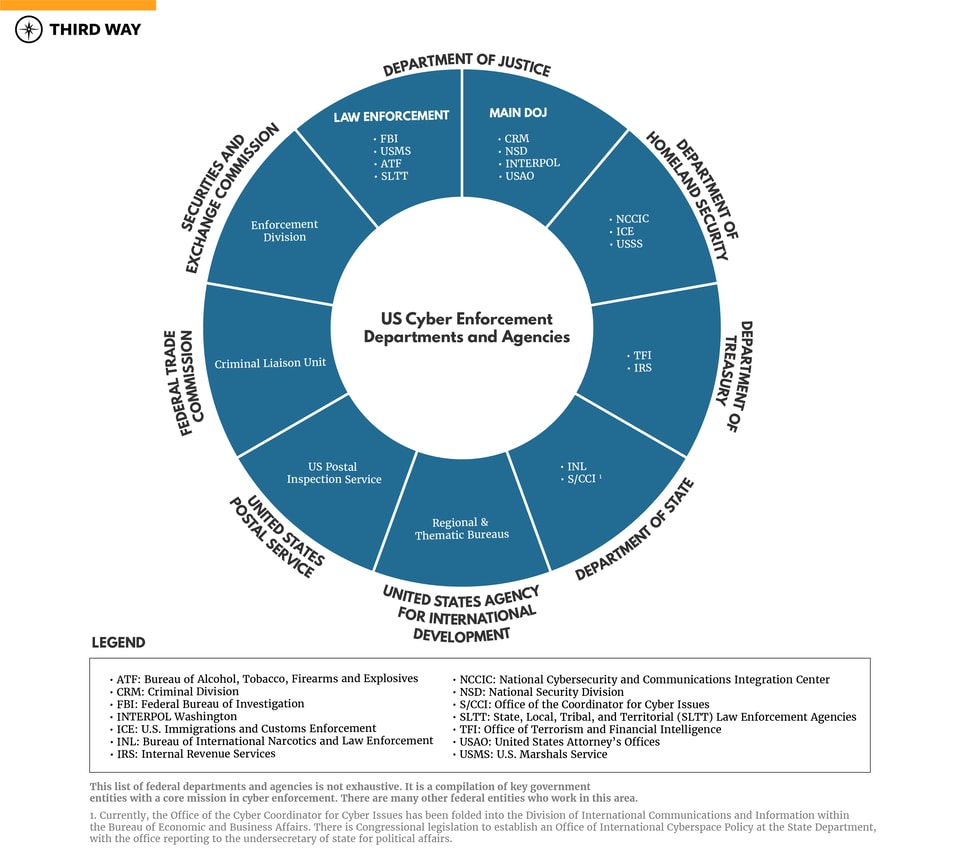

There are eight federal departments that have a key role in cyber enforcement. These entities have a role in cybercrime prosecutions, investigations, international cooperation efforts, and international law enforcement capacity building. Yet, the resources provided to these government entities have not been sufficient to stem the growing cyber enforcement gap. As such, Congress should assess the current levels of resources and authorities involved in cyber enforcement to ensure they are aligned to reduce the cyber enforcement gap.

There are eight federal departments and several law enforcement agencies involved in cyber enforcement. This includes the Department of Justice, which is the main US law enforcement agency that leads much of the government’s work to prosecute cybercrime through its Criminal Division, National Security Division, and Office of the United States Attorneys. The Department of Justice also has cybercrime investigation functions through its law enforcement agencies such as the FBI. The Department of Homeland Security has an active role in cybercrime investigations as a result of overseeing the United States Secret Service and US Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Homeland Security Investigations. Further, the Department of Treasury oversees several offices with a role in investigating financial crimes as well as administering US cyber-related sanctions. On the international front, the Department of State, programs at the Department of Justice, and the United States Agency for International Development work to build the capacity of global criminal justice systems to investigate and prosecute cybercrimes and boost international cooperation in these efforts. State and local law enforcement agencies also lead on many cybercrime investigations.

With the expanding list of entities involved in cyber enforcement, issues such as mission duplication, misallocation of resources, and unclear lines of authority have arisen. While each of these agencies has a vital role in cyber enforcement, there are also some similar or overlapping responsibilities between them. At the federal level in particular, this can lead to inefficiencies, redundancies, and difficulties in ensuring congressional oversight efforts are tied to an overarching strategic cyber enforcement approach across agencies.5

To help make sense of all of the different government entities involved in cyber enforcement, Third Way has prepared a Reader’s Guide for Members of Congress and their staff. This document is meant to give a snapshot of the key entities involved in making progress in reducing the cyber enforcement gap. This list is not exhaustive, and some government agencies were not included if they do not have a predominant focus on cyber enforcement.6 The list of Departments, Agencies, Offices, Sections, and Divisions were selected because of their key role in either cybercrime prosecutions, investigations, international cooperation, or international capacity building.

The following agencies play a critical role in US cyber enforcement efforts:

Department of Justice (DOJ)

Criminal Division (CRM)

Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section (CCIPS)

- CCIPS investigates and prosecutes computer crimes and works to prevent the theft of intellectual property (i.e. copyright, trademark, or trade-secrets).7

Organized Crime and Gang Section (OCGS)

- OCGS investigates and prosecutes transnational organized crime groups with a cyber nexus.8

Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section (MLARS)

- MLARS leads DOJ’s asset forfeiture and anti-money laundering enforcement efforts and prosecutes international cybercrime cases involving financial institutions.9

Office of International Affairs (OIA)

- OIA leads DOJ in its international cooperation efforts in cybercrime investigations through five main areas: (1) extradition and removal of cybercriminals; (2) transfer of sentenced cybercriminals; (3) international cybercrime evidence gathering between countries; (4) providing legal advice to DOJ leadership and prosecutors; and (5) international relations and treaty matters.10

Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Development Assistance and Training (OPDAT)

- OPDAT works to target transnational cybercriminal organizations and leads an international prosecutorial capacity-building mission, which works with partner governments to improve responses to computer crime and strengthen cybersecurity.11

International Criminal Investigative Training Assistance Program (ICITAP)

- ICITAP works with foreign governments to build the capacity of their law enforcement institutions on a wide range of issues, including cybercrime investigations.12

National Security Division (NSD)

National Security Cyber Specialists (NSCS)

- NSCS is a network of nearly 100 prosecutors located in US Attorney’s Offices nationwide and cyber experts from NSD and CCIPS who can be deployed to provide expertise in cyber investigations.13

Counterintelligence and Export Control Section (CES)

- CES prosecutes and investigates threats involving cyber-based espionage and state-sponsored cyber intrusions.14

Counterterrorism Section (CTS)

- CTS leads DOJ on combating emerging and evolving terrorism threats in cyberspace.15

INTERPOL Washington

Operational Divisions (OD)

- OD works with domestic and foreign law enforcement partners to locate, apprehend, and return malicious cyber actors wanted by the United States who are in foreign countries and malicious cyber actors wanted by foreign countries in the United States. It also serves as a dedicated channel for exchanging cyber intelligence with the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL).16

Office of the General Counsel (OGC)

- OGC is responsible for overseeing DOJ’s Red (fugitive) Notice program, used to facilitate the return of international fugitives through INTERPOL and develops and reviews all agreements and Memoranda of Understanding between INTERPOL Washington and its partnering agencies. 17

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

Criminal, Cyber, Response and Services Branch (CCRSB)

Cyber Division

- The Cyber Division at FBI Headquarters leads and coordinates the agency’s efforts to investigate internet crimes, cyber-enabled terrorism, unauthorized computer intrusions, and cyber fraud.18

Cyber Action Teams

- Cyber Action Teams provide rapid incident response on major computer intrusions and cyber-related emergences around the globe, including gathering vital intelligence in cybercrime investigations.19

Cyber Watch (CyWatch)

- CyWatch is the FBI's 24-hour command center responsible for coordinating domestic law enforcement response to criminal and national security cyber intrusions, tracking victim notification, and coordinating with other federal cyber centers. 20

National Cyber Investigative Joint Task Force (NCIJTF)

- The NCIJTF is a multi-agency task force led by the FBI with the primary responsibility to coordinate, integrate, and share information to support cyber threat investigations, supply and support intelligence analysis for community decision-makers on cyber threats, and synchronize joint efforts across the different agencies.21

iGuardian

iGuardian is a secure portal allowing FBI partners within critical telecommunications, defense, banking and finance, and energy infrastructure sectors to report cyber intrusion incidents to the FBI in real time.22

Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3)

- The IC3 is the FBI’s public reporting mechanism on internet-facilitated criminal activity, which allows the FBI to receive, develop, and refer criminal complaints regarding cybercrime.23

National Cyber Forensics & Training Alliance (NCFTA)

- The NCFTA brings together law enforcement, private industry, and academia to share information to stop emerging cyber threats and mitigate existing ones.24

Cyber Initiative and Resource Fusion Unit (CIRFU)

- CIRFU is the cyber unit attached to the NCFTA and analyzes cyber threats and eliminates false leads before cyber cases are referred to other law enforcement agencies.25

International Operations Division

Legal Attaché (Legat) Program

- Legal attaché offices or Legats are FBI offices located in US embassies abroad where stationed special agents and other overseas personnel can assist international law enforcement partners in their response to and investigation of cybercrimes.26

Science and Technology Branch

Operational Technology Division

National Domestic Communications Assistance Center (NDCAC)

- NDCAC is a hub for law enforcement and shares knowledge and resources on issues involving real-time and stored communications to address challenges posed by electronic evidence collection. 27

U.S. Marshals Service (USMS)

Fugitive Apprehension Decision Unit

- The Fugitive Apprehension Decision Unit is authorized to investigate and apprehend fugitives in the United States and abroad, including cybercriminals wanted by US law enforcement. 28

Asset Forfeiture Program

- The Asset Forfeiture Program has the authority to seize cryptocurrency (e.g., Bitcoin, Ether, and Monero) used by cybercriminals, which is vital for disrupting their criminal networks and recovering stolen assets.29

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF)

- ATF has jurisdiction over the trafficking of explosive or incendiary devices, bomb threats, and firearms over the internet.30

State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial (SLTT) Law Enforcement Agencies

- SLTT law enforcement agencies work closely with their federal law enforcement counterparts to investigate cybercrime cases with a SLTT nexus.

United States Attorney’s Offices (USAO)

- USAO’s located nationwide work with DOJ to prosecute cybercrimes cases in their districts.

Department of Homeland Security

National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC)

- The NCCIC serves as the nation’s 24/7 hub for cyber information, technical expertise, and cyber incident response. 31

The United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT)

- US-CERT works with federal agencies, the private sector, the research community, and state and local governments by analyzing cyber incidents reported to the government, disseminating cyber threat warnings, and providing on-site incident response capabilities to federal and state agencies.32

U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE)

Homeland Security Investigations (HSI)

- HSI has authority to investigate criminal activity conducted on or facilitated by the internet. Their Cyber Crime Center delivers computer-based technical services to support domestic and international investigations into cross-border crime conducted over the internet.33

United States Secret Service (USSS)

National Computer Forensics Institute (NCFI)

- The NCFI is the nation’s only federally funded training center dedicated to instructing state and local law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and judges in cybercrime investigations.34

Electronic Crimes Task Forces (ECTFS)

- ECTFS are interagency task forces organized of USSS, state, local, and other federal law enforcement that conduct investigations into cryptocurrency, bank fraud, virus and worm proliferation, unauthorized device access, and a variety of other computer crimes.35

Electronic Crimes Special Agent Program (ECSAP)

- ECSAPs are located in USSS field offices across the country and are computer investigative specialists qualified to conduct examinations of all types of electronic evidence.36

Department of Treasury

Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN)

- FinCEN works to identify sources of revenue for malicious cyber actors and their attempts to access and exploit international financial systems.37 FinCEN uses and collects Suspicious Activity Reports (SARS) that financial institutions must submit as sources of intelligence and works with law enforcement to neutralize reported threats.

Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC)

- OFAC has the authority to issue economic and trade sanctions against persons engaging in significant malicious cyber-enabled activities and certain nation-state actors perpetrating malicious cyber activity against the United States.38

Internal Revenue Services (IRS)

Criminal Investigation (CI)

- CI is composed of financial investigators and all CI employees are required to complete cyber training. Special agents use specialized forensic technology to recover financial data that may have been encrypted, password protected, or hidden by other electronic means.39

Department of State

Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL)

Office of Anti-crime Programs

- The Office of Anti-Crime Programs implements two programs to combat cybercrime: (1) a crime program that works with international partners to provide training and technical assistance aimed at strengthening law enforcement capacity to investigate and bring to justice cybercriminals; and (2) a criminal justice program that supports international law enforcement academies to strengthen international cooperation around cybercrime and other security threats.40

High Tech Crime Global Law Enforcement Network (GLEN)

- Through the GLEN, INL helps to coordinate and resource the network of International Computer Hacking and Intellectual Property Advisors (ICHIPS), which are DOJ attorneys located in key regions working to enhance their foreign law enforcement partners capacity to investigate and prosecute cyber and intellectual property crime.

Office of the Coordinator for Cyber Issues (S/CCI)41

- The Office was created in 2011 and coordinates the Departments’ global diplomatic engagements on cyber issues. It has since been folded into the Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs.42

United States Agency for International Development (USAID)

- USAID, through its foreign assistance funding, implements a number of cybercrime capacity building programs through several of its regional and thematic bureaus. 43

United States Postal Service (USPS)

US Postal Inspection Service

Cybercrime Unit (CU)

- The CU investigates and provides analytical support to criminal activities affecting the USPS computer networks and field investigations related to the dark web and cryptocurrencies.44

Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

Criminal Liaison Unit

- The Criminal Liaison Unit helps prosecutors bring criminal consumer fraud cases involving the internet, telemarketers, and identity theft. They train prosecutors and investigators on identifying suspects and witnesses using the Consumer Sentinel Network,45 which is an online investigative tool available to law enforcement that contains consumer complaints involving a variety of fraud issues, including identity theft.46

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

Enforcement Division

Cyber Unit

- The Cyber Unit works on cyber-related securities misconduct such as hacking to obtain material nonpublic information, misconduct perpetrated using the dark web, and intrusions into retail brokerage accounts.47

To reduce the cyber enforcement gap, Congress must evaluate whether key cyber enforcement entities have the necessary funding to make progress.

In order to make progress in reducing the cyber enforcement gap, Congress must evaluate whether the key entities involved in identifying, stopping, and bringing to justice malicious cyber actors have the required funding they need.

In order to assist Members of Congress and their staff in doing this evaluation during the FY 2020 budget process,48 Third Way has compiled the budget history of key entities across the US government engaged in cyber enforcement (based on publicly available data). Only those entities whose budget levels are specifically listed in the Executive Branch’s budget request and corresponding materials are included. As such, we were unable to ascertain funding levels for all of the specialized units and sections involved in cyber enforcement if their budgets are not made publicly available.

Overall, funding for key cyber enforcement entities has remained consistent with a few increases from FY 2017-2019. However, in previous years the Trump Administration has requested to eliminate funding for the National Computer Forensic Institute (NCFI). Congress should work to ensure it has sufficient funding to fulfill its mandate. Even at its height, the NCFI was only running at about one-third capacity and would require close to $35 million to be at full capacity49— far from the $4 million currently budgeted. Further, dedicated funding for the State Department’s Office of the Coordinator for Cyber Issues has been eliminated from the budget request, which should be re-established along with the authorization for the Office led by an Ambassador. Although overall funding for cyber enforcement has largely been consistent, what is clear is that the current allocation of funding is not enough to reduce the cyber enforcement gap—particularly for entities like the FBI, USSS, and the State Department’s INL Bureau. Congress should evaluate whether strategic boosts in funding for certain key US entities involved in cyber enforcement are necessary in order to provide them with the resources needed to stop, identify, and punish malicious cyber actors and put a large dent in the cyber enforcement gap.

Conclusion

The United States is facing a cybercrime wave, and based on our research less than 1% of these crimes ever see an arrest of the perpetrator—a large cyber enforcement gap. There are a multitude of government entities with the responsibility to reduce this cyber enforcement gap, including federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies and the Department of State. Yet, despite the number of entities involved in cyber enforcement, the cyber enforcement gap remains large. When reviewing the FY 2020 budget from the Trump Administration, Members of Congress and their staff should familiarize themselves with the scope of entities involved in cyber enforcement and assess whether they have sufficient funding to make progress.