Report Published October 20, 2015 · Updated October 20, 2015 · 19 minute read

A Path to Recovery for Americans with Serious Mental Illness

Jacqueline Garry Lampert & David Kendall

Lyn, a consultant from Boston, Massachusetts, documented the cost of her journey to mental health recovery. In her self-described “worst year,” she endured one four-month hospitalization as well as several shorter stays, ambulance rides to the emergency room following suicide attempts, partial hospitalizations, outpatient therapy, psychopharmacology services, and prescription medication. When she added it up, the entire annual cost of Lyn’s care and other supports, born fully by the government, was more than $208,000. In a more “average year,” the total cost was just above $132,000. For 29 years, before she was connected with appropriate services that facilitated her recovery, Lyn estimates the total cost to the state and federal governments of her care and support services was $3.9 million.1

Lyn began her journey to recovery when she started volunteering at the Boston University Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation. There she learned that she could work toward recovery within the limitations of her own illnesses and felt hopeful for the first time in a long time. Now, Lyn pays taxes on her full-time and consulting income, rather than receiving SSDI and SSI, and she purchases her own health insurance through her employer, rather than receiving Medicaid. Enrolling individuals with severe mental illness in assertive community treatment programs could help patients take a substantial step toward recovery while also saving the federal government billions of dollars due to better patient care.

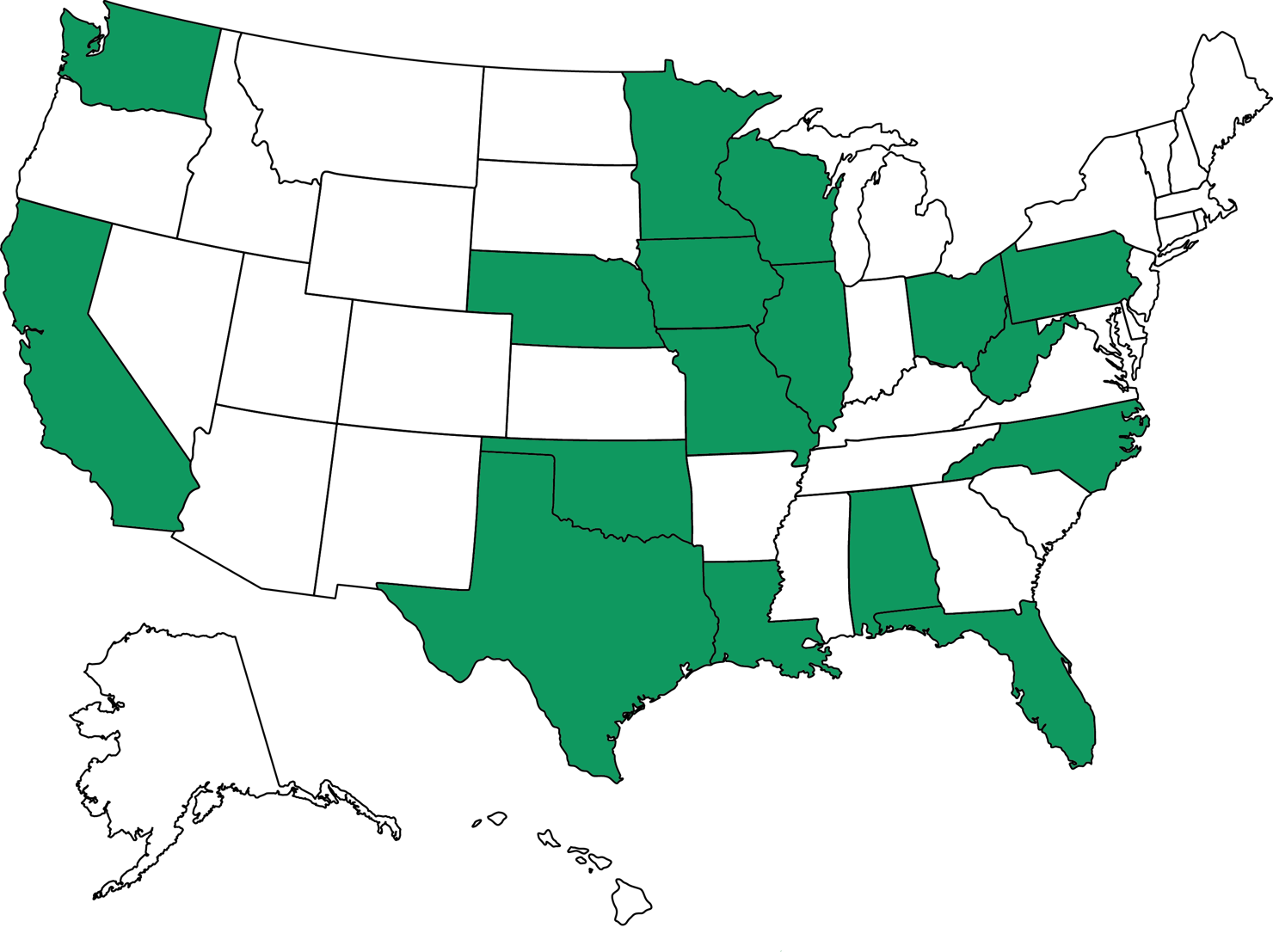

This idea brief is one of a series of Third Way proposals that cuts waste in health care by removing obstacles to quality patient care. This approach directly improves the patient experience—when patients stay healthy, or get better quicker, they need less care. Our proposals come from innovative ideas pioneered by health care professionals and organizations, and show how to scale successful pilots from red and blue states. Together, they make cutting waste a policy agenda instead of a mere slogan.

What Is Stopping Patients From Getting Quality Mental Health Care?

General mental disorders afflict 26% of American adults, but the incidence of serious mental illness is more concentrated, ranging from 4-6% of the population.2 Individuals with severe mental illness often experience recurring mental health crises and may be heavy users of inpatient psychiatric and emergency department services.3 Nearly half of those with one mental illness also meet the criteria for two or more disorders, and more than 34% of those with serious mental illness rate their health as only fair or poor, compared with 10.7% of Americans with no mental illness.4 Mental disorders are the leading cause of disability in the United States and cost the nation more than $193 billion per year in lost earnings alone.5 In total, mental illness costs the United States as much as $444 billion per year.6 One-third of the total is spent on medical care, and the remainder goes toward disability payments and lost productivity.

Nationwide, mental health care coordination falls short, resulting in significant service fragmentation and, in some cases, reduced access to care.7 A shocking 35% of adults with mental illness involving serious impairment receive no mental health treatment. This is due to various reasons, such as no perceived need for treatment, wanting to handling the problem on one’s own, fear of stigma, and thinking the condition will improve over time as well as the lack of trained professionals and facilities.8 The most common course of treatment for those who do get care is prescription medication, followed by outpatient treatment and inpatient treatment, and treatments are often used in combination.9

If prescription drugs are ineffective or if an individual experiences an acute mental health crisis, such as a suicide attempt, the typical response is institutionalization, either in a hospital, psychiatric hospital, or prison. Institutionalization is the more common response because assessing a patient’s fitness for and connecting them with high-quality, appropriate community treatment options can be tedious and time consuming. Institutional care is, for the most part, readily available, at least in an acute situation to prevent patients from harming themselves or others. But while available, institutional care may waste time and resources, such as boarding in a hospital emergency department for days or weeks while awaiting an inpatient bed or even prison.10 Put another way, our system has a tendency toward institutionalizing an individual with severe mental illness in order to address an immediate situation—but does far less to provide complete treatment and services that are better for the patient and cost less in the long run.

Nationwide, 4% of emergency department visits are driven by behavioral health care needs, and nearly twice as many Americans with serious mental illness experience an emergency department visit each year compared with those who have no mental health diagnosis.11 In addition:

- Mental health disorder diagnoses drove nearly 4% of community hospital admissions in 2010, with a mean cost per stay of $6,764.12

- Approximately 9% of these patients were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of initial discharge with a mood disorder as their principal readmitting diagnosis at a mean cost per stay of $7,019.13 Readmissions for these patients regardless of the reason were more than 15%.14

- More than 30% of Medicare beneficiaries with psychiatric discharges are readmitted to either a freestanding inpatient psychiatric facility or a psychiatric unit during the year.15

This churn of patients with severe mental illness drives up health care spending, and often a small number of individuals with extremely severe mental illness are responsible for an outsized share of health care costs.16 For example, of the 19,000 Missouri Medicaid beneficiaries diagnosed with schizophrenia, the most expensive 2,000 had Medicaid costs of $100 million in 2003, with 80% of claims related to urgent care, emergency department, and inpatient care.17 These patients represented 0.2% of Missouri Medicaid beneficiaries but drove 2.4% of annual Medicaid spending.18

The socioeconomic costs of serious mental illness are also profound. Americans with serious mental illness are much more likely to be unemployed than those with no mental illness (9.1% compared to 5.8%),19 and twice as likely to have unstable housing.20

Mental illness strikes at a young age. One-half of everyone with chronic mental illness have the first symptoms by age 14, and three-quarters have symptoms by age 24.21 The price of mental illness is especially high for adolescents with severe emotional disturbance, who are:

- Nearly twice as likely to have failed a grade;

- More than 10 times as likely to have dropped out of school;

- Twice as likely to have been arrested; and

- More than 10 times as likely to have spent time in a juvenile corrections facility as adolescents with low emotional disturbance.22

If serious mental illness strikes in adolescence without effective treatment, making up the ground lost due to failed grades, dropping out, or incarceration can be nearly impossible.

Perhaps the most intense measurable difference between Americans with and without any type of mental illness is in the criminal justice field. Deinstitutionalization, which began with President Kennedy’s signature of the Community Mental Health Act in 1963, achieved only half of its goal of caring for the mentally ill in the community instead of warehousing them in psychiatric hospitals. States reduced funding for and closed psychiatric hospitals, but neither the states nor the federal government provided adequate funding to meet the growing demand for community mental health services.23 The recent recession caused many states to enact further, devastating cuts. From 2009 to 2012, states cut $5 billion in mental health services and eliminated 4,500 public psychiatric hospital beds, almost 10% of the total supply.24 Many individuals released into the community without the support they needed ended up in jail, and, today, 20% of prison inmates have a severe mental illness, compared with 4-6% of the general population.25 Some estimates indicate there are 10 times as many individuals with severe mental illness in prisons and jails as are in state psychiatric hospitals.26 Individuals with severe mental illness are more than three times as likely to have been arrested during the past year as those with no mental illness (7.7% versus 2.2%), and 40% of individuals with a severe mental illness will have spent time in a corrections facility at some point in their lives.27

Where Are Innovations Happening?

A number of innovations are happening across the country to help patients with mental health issues—including with assertive community treatment (ACT).

ACT is a proven team-based model of providing highly individualized services to those with “the most intractable symptoms of severe mental illness and the greatest level of functional impairment.”28 The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) advocates for this model, which the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) also endorses as an evidence-based practice.29 Research repeatedly affirms that, when targeted to those with severe mental illness, ACT reduces hospitalization, increases housing stability, and improves quality of life for participants.30

The ACT model evolved from work in Madison, Wisconsin, and was first launched in 1972.31 Its purpose is to reduce or eliminate debilitating symptoms of mental illness and acute episodes or recurrences. This requires ensuring patients have the necessities of life as well as treatment so they can ultimately live independently and lead a productive life.32

A multidisciplinary team of professionals with expertise in psychiatry, nursing, social work, substance use treatment, and vocational rehabilitation assume direct responsibility for providing all services needed by the consumer, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for as long as services are needed.33 Services are provided in vivo—in the setting or context in which problems are likely to arise and where support is needed.34 A staff-to-consumer ratio of 1-to-10 is generally recommended, though a lower ratio may be required, at least initially, for teams serving consumers with particularly intensive needs. Team members are cross-trained in each other’s areas of expertise as much as is feasible.35

In an effort to reduce use of its two state psychiatric hospitals, Washington State launched a statewide network of ten ACT teams in 2007.36 The teams were also trained in “person-centered and recovery-oriented services,” making the program slightly different from the original ACT model, but demonstrating the model’s flexibility to meet local needs. The state invested $2.4 million for development and training and $10.4 million per year for operational expenses. ACT participation resulted in:

- An average reduction of 32-33 days per person per year in state hospital use.37 Notably, ACT did not reduce the number of times patients had to go to a state hospital use, but it did reduce the number of days they had to spend in the hospital.38

- Those with the highest state hospital use before the start of treatment had savings ranging from $16,719 to $19,872 per person per year.39

- Overall, savings attributable to reduced hospital use ranged from $11,257 to $12,699 per person per year for total savings of $4 million to $5.7 million when weighted by sample size.40

It is important to note that the goal of ACT isn’t to reduce costs but make patients well. That is why, in some cases, ACT participants with low levels of initial state hospital use had higher use of alternatives to state hospitalization, such as local hospitals, emergency departments, and crisis stabilization units. But after enrollment, those ACT participants who needed intensive services received them in the community rather than in state hospitals.41

In a separate project in Washington State, King County is adopting the ACT program to the criminal justice population through a program called forensic assertive community treatment (FACT).42 Through a focus on individuals with extensive criminal histories and a history of homelessness or who are at risk of becoming homeless, King County’s FACT program aims to reduce use of the criminal justice system and of inpatient psychiatric services while improving housing stability and community tenure. The evaluation of King County’s FACT program is particularly strong because individuals were randomly assigned to either participate in FACT or to receive services as usual. FACT participants experienced statistically significant reductions in jail and prison bookings and jail days—45% and 38%, respectively.

Finally, utilizing a variety of funding sources (including state appropriations, Medicaid billing, redirection of existing resources at a state-operated community mental health center, a federal grant, and a state Medicaid revenue source), ACT teams in Oklahoma were successful in reducing the need for inpatient care and reducing incarceration by focusing enrollment outreach on individuals with significant hospitalizations or those entering or leaving the criminal justice system.43 These goals were achieved by increasing medication compliance, securing employment, keeping families together and assisting with basic needs, such as housing, among other tools.44 As of April, 2006, 14 ACT teams in Oklahoma were serving 575 people with serious mental illness, with the capacity to serve as many as 950 individuals. In comparing data from the year prior to ACT enrollment for 124 individuals with any hospitalization with data from the year following ACT enrollment:

- The number of inpatient days fell from 5,233 to 1,942, a 63% reduction.45

- The number of individuals hospitalized also fell by 53%.

- Total number of jail days decreased from 1,050 to 315, a 70% reduction.

How Can We Bring Solutions to Scale?

Enrolling individuals with severe mental illness in assertive community treatment reduces hospitalizations, health care, and prison costs, and improves patients’ lives. Congress should expand ongoing efforts to enable states to expand the use of ACT teams throughout the country using the following four steps:46

First, expand the certified community behavioral health clinics demonstration to all states. In 2014, Congress authorized an eight state demonstration program for a new type of community-based health clinic focused on behavioral health. Under this program, first proposed by Sens. Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) and Roy Blunt (R-MO), and Reps. Doris Matsui (D-CA) and Leonard Lance (R-NJ), states would provide clinics with a periodic payments for behavioral health services for each person under their care.47 The payment model is based on the prospective payment system for federally qualified health centers, which pays a fixed rate for each office visit. The demonstration program provides states with a two-year boost in federal matching funds for Medicaid services. Expanding this demonstration would ensure that residents of all states would have the chance to receive intensive services for people who need ACT services by providing a single source of funding. The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act by Reps. Tim Murphy (R-PA) and Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX) moves in this direction by increasing the demonstration sites to 10 states and lengthening the time frame from two years to four years.48

Second, provide start-up funds. The start-up costs of assembling and training staff and establishing coordination plans for an ACT team range from $25,000 to $50,000 per team.49 Funding for these initial costs is currently not covered by Medicare and Medicaid. Instead, it must compete for funding through Community Mental Health Services Block Grant funds as well as state and county mental health funds that primarily fund ongoing service.50 Congress should provide states with funding set aside for start-up costs.

Third, set performance standards. In order to ensure the effective use of start-up funds, Congress and the Administration should set performance standards for ACT using nationally recognized organizations like the National Quality Forum that use existing standards that can apply across a wide range of programs and care settings. Different organizations have established different standards for ACT, which vary based upon the needs of the specific population being served.51 The model has evolved to integrate evidence-based and state-of-the-art practices.52 However, ACT programs with higher fidelity to the original model have been shown to reduce hospitalizations by 23 percentage points more than programs with lower fidelity to the model.53 Indeed, ACT is most effective at reducing the proportion of participants hospitalized and the length of stay when targeted to individuals at greatest risk of hospitalization.54 ACT may also be targeted to serve subpopulations of those with severe mental illness, such as homeless persons, individuals entering or leaving the criminal justice system, or veterans.55 The Mental Health Reform Act of 2015, by Sens. Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Chris Murphy (D-CT), would—among many other important improvements in mental health care—also further the use of evidence-based programs like ACT by requiring the Department of Health and Human Services to approve only evidence-based grants.56

Finally, share federal savings. Even with the availability of start-up funding, some states may choose not to establish ACT teams. To further incentivize participation, Congress should allow states to share in any Medicare and Medicaid savings ACT generates. While the enhanced federal matching funds under the state demonstration programs mentioned above provides some recognition of the potential for federal savings, that enhanced match will last only two years under the demonstration. One model for a permanent distribution of any savings is gain sharing—a partnership between the federal government, private sector stakeholders, and the states that recognizes actions taken by one sector may result in the accrual of savings to another sector.57 Congress would establish a framework for the submission of bids by states for the Medicare shared savings rate. States would invest any Medicare shared savings in ACT or other critical parts of the mental health care continuum.

Potential Savings

The potential savings from expanded use of the ACT program include reduced hospitalizations, less time needed in the hospital when a stay is required, and lower prison costs. While the magnitude of savings in relation to the costs of ACT needs fuller study, Congress can look to the eight-state demonstration program for concrete results on cost savings in the near term. It calls for improving mental health services using savings to pay for additional costs so that the federal government has no net costs. Third Way will be evaluating additional payment models for these services and potential savings in the coming months.

Questions and Responses

What is the source of ACT start-up funding?

When appropriately targeted to individuals with severe mental illness at greatest risk for hospitalization, ACT is proven to reduce both the number and length of hospitalizations. To the extent that ACT clients are Medicare beneficiaries, this will generate savings to Medicare. As discussed above, a portion of these Medicare savings will be shared with states to incentivize participation in ACT team creation, and the remaining savings will be used to reimburse the federal government for start-up funding. Reduced use of inpatient hospital treatment is also likely to generate savings to the Medicaid program, and these savings will automatically be shared between the states and the federal government according to each state’s Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP). The federal government will use its share of Medicaid savings to pay for ACT start-up funding.

How will states generate savings from federal start-up funds?

States will receive federal grants to fund the start-up of ACT teams and will share in any savings ACT generate to the Medicare program, for example, through reduced hospitalizations and reduced lengths of stay including at state psychiatric hospitals, which are primarily funded by states. In addition, states will share in any savings ACT generates to the Medicaid program. Finally, by reducing time spent in jail by individuals with severe mental illness, county and state corrections facilities will experience savings. States will be required to reinvest Medicaid and corrections facilities savings in ACT or in other elements of the mental health care continuum.

How would patients for whom ACT is an appropriate treatment option be identified and connected to an ACT team?

Referral to ACT services could continue in much the same way as it occurs today, which may vary by state. For example, in New York, referral to ACT may be made by a consumer on their own behalf, a family member, a mental health provider (including an agency or hospital), the police, or the court system.58 However, ACT is most cost-effective when targeted to individuals with severe mental illness and high hospital use or at greatest risk of hospitalization.59 Appropriate use of this treatment resource is key.

Combining increased use of ACT with a program like Critical Time Intervention (CTI) could help ensure the cost-effectiveness of ACT services. Originally developed at Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute, CTI is listed in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices. CTI aims to prevent homelessness and other adverse outcomes for people with mental illness during the “critical time” of transition from hospitals, shelters, prisons, and other institutions to the community.60 CTI uses two main levers to achieve these goals: strengthening the individual’s ties to services and to their community, and providing support during the difficult time of transition. Ideally, the CTI worker begins to engage the client before the client moves into the community and partner with care providers (if any) in the institution from which the client is transitioning. In the first phase of the CTI model, the CTI worker assesses existing resources for care in the community. It is during this time that the CTI worker may determine if ACT is an appropriate treatment for the client or whether other community-based services should be utilized.

We foresee that CTI workers will become experts in the strengths and weaknesses of the local mental health care system. Because they will be constantly assessing the availability of community-based treatment services for their clients, CTI workers will be aware of any holes in the system and may identify areas to which current resources might be redirected. These workers should serve as expert consultants as policymakers consider ways to improve mental health care.

How do we transition toward patient-reported outcomes for mental illness?

In order to encourage personalized, integrated and recovery focused care, it is necessary to create quality measures that are aimed at measuring recovery. The National Committee for Quality Assurance is working toward measurement-based care in mental health care with the goals of better understanding whether treatment is working.61

What about individuals with less severe mental illness?

Director of the National Institute of Mental Health Thomas Insel stated, “The way we pay for mental health today is the most expensive way possible. We don’t provide support early, so we end up paying for lifelong support.”62

As we have previously indicated, ACT is most appropriate for, and most effective when targeted to, individuals with severe mental illness. ACT is just one component of the mental health continuum of care, and investing in more ACT teams will fail the cost-effectiveness test without the robust involvement of other mental health services on the continuum of care. Ready, early access to lower levels of care is critical to preventing escalation of the disease such that individuals require the intensity of ACT services.

Both ACT and lower levels of care will require an appropriately trained mental health care workforce. Start-up grants will, in part, fund training for ACT staff in this model of care, but the need to invest in the mental health care workforce extends across the continuum of care. Investments in workforce development and lower levels of care are unlikely to yield the cost savings on the scale that ACT has the potential to do, but both are critical to ensuring consumers get the appropriate level of care.