Report Published December 5, 2024 · 16 minute read

A Policymaker’s Guide to America’s Hospital Financing System

Darbin Wofford

Takeaways

Hospitals are the single largest category of health care spending. And yet, the gap between rich and poor hospitals is growing wider. That’s why it is critical to understand the federal government’s role in paying hospitals for care. In this report, we break down the multitude of funding streams for hospitals across four key areas: Medicare, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the tax code, and the private sector.

American spending on health care is projected to reach $5 trillion in 2024.1 One third of that goes towards hospitals.2 Spending on hospitals is the single largest category of health care—more than prescription drugs, insurance premiums, and doctors’ visits combined. Meanwhile, price increases for hospital care continue to outpace inflation, along with other areas like physician care and prescription drugs.3

Despite dips during the COVID-19 pandemic and early 2022, hospital revenues are at an all-time high.4 Although the hospital industry took some hits during the COVID-19 pandemic and early 2022, hospitals are on a rapid recovery and expected to grow.5 A majority of hospitals have positive operating margins, and some even exceed 30%.6

Amid these trends, the hospital industry claims federal reimbursements are insufficient, forcing them to increase prices for commercial payers. But is that so? It is important for policymakers to understand how hospitals are financed, especially as debate increases over reforms to the system. In this report, we break down the funding streams in four key areas: Medicare, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), the tax code, and the private sector.

This report is part of a series called Fixing America’s Broken Hospitals, which seeks to explore and modernize a foundation of our health care system. A raft of structural issues, including lack of competition, misaligned incentives, and outdated safety net policies, have led to unsustainable practices. The result is too many instances of hospitals charging unchecked prices, using questionable billing and aggressive debt collection practices, abusing public programs, and failing to identify and serve community needs. Our work will shed light on issues facing hospitals and advance proposals so they can have a financially and socially sustainable future.

How are hospitals doing?

Here’s a snapshot:

- Types of Hospitals: Of the 6,120 hospitals in the United States, 84% are called community hospitals. Other types of hospitals include government-run and psychiatric hospitals.7 While a majority of community hospitals are general hospitals, offering a wide range of medical services, some are specialty hospitals that focus on specific populations or health needs, like children, orthopedics, or obstetrics and gynecology, among others.

- Hospital Revenue: Despite dips during the COVID-19 pandemic and early 2022, hospital revenues are at an all-time high.8 Hospitals have many fixed costs, including building management, utilities, information technology, and their workforce.9

- Hospital Prices: Price increases for hospital care continue to outpace inflation and prices in other areas like physician care and prescription drugs.10

- Haves and Have Nots: While the hospital industry is doing extremely well writ large, hospitals in rural and vulnerable communities are operating on thin margins or even in the red.11 A third of rural hospitals are at risk of closure.12 The gap is increasing between hospitals that are doing well and those that are not.

Hospitals’ Impact on Federal Spending and Other Sources

America’s spending on health care is projected to grow substantially—from $5 trillion in 2024 to $7.7 trillion in 2032, a 54% increase.13 Of this, $2.3 trillion will go to hospitals in 2032.14 Hospitals account for roughly a third of all spending across all types of coverage, public and private. And they receive more money than other sectors in health care. Both of these trends are projected to continue.

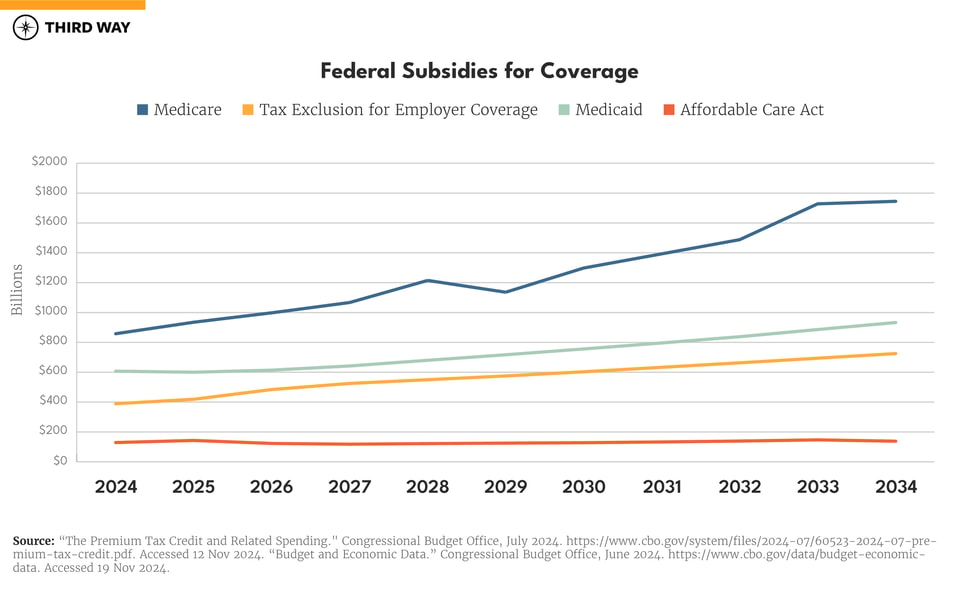

Hospitals are part of the larger problem with health care spending. Health care is the second largest category of federal spending behind Social Security. Medicare and Medicaid will drive most of the spending growth over the next 10 years. The Congressional Budget Office projects that spending on Medicare will grow by 97%, Medicaid by 54%, and the health plans through the Affordable Care Act exchanges by 10% over the next decade.15 Additionally, it projects the tax break for employer coverage, which exempts health benefits from income and payroll taxes, will grow by 86% over the next decade.16

Funding Stream 1: How Medicare pays hospitals.

Hospitals receive more money from Medicare than any other single payer.17 Medicare is a federally administered health insurance program that covers seniors and disabled Americans. Americans are eligible for Medicare at 65 – or earlier if they are disabled or have end-stage renal disease. Medicare has four categories of coverage:

- Part A for stays in hospitals and other facilities.

- Part B for doctors, other health professionals, physician-administered drugs, and same-day procedures.

- Part C for private health plans, known as Medicare Advantage, which covers all Parts A and B and may also include prescription drugs.

- Part D for prescription drugs.

Financing for Parts A&B

Medicare pays hospitals through Part A for inpatient care and Part B for outpatient care, but the two parts have different sources of financing. Medicare Part A is financed through the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, which receives its funds through payroll taxes from employers and employees. The costs are climbing as hospitals receive more money and more people retire.18 Medicare Part B is financed through federal revenues and beneficiary premiums.

Payments for Parts A&B

Medicare’s payments to hospitals are paid through “fee-for-service,” meaning hospitals receive reimbursement for the individual services they provide. These rates are determined by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. In Parts A and B, hospital rates are specifically determined in the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System and the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System. In some cases, both systems can pay a package price for all of a hospital’s services during a procedure like heart surgery or a hip replacement.

Medicare Advantage (Part C)

Just under half of Medicare patients are enrolled in traditional Medicare, which includes Parts A and B. Traditional Medicare allows patients to see any doctor or hospital participating in Medicare, but many beneficiaries in traditional Medicare often purchase supplemental coverage to protect against high out-of-pocket costs since the program does not have an out-of-pocket maximum.19 Fifty-four percent obtain coverage through Medicare Advantage, which offers seniors a choice of private health plans.20 Medicare Advantage plans provide coverage for the same services as Parts A and B, and they often include coverage for prescription drugs, an out-of-pocket maximum, and other benefits like dental, hearing, and vision coverage. Unlike traditional Medicare, most Medicare Advantage plans do not include every hospital and doctor that participate in Medicare. Instead, plans negotiate prices directly with providers to build their networks, which lowers costs for patients.

Disproportionate Share & Uncompensated Care

Medicare also supplements hospital payments for the care of low-income and rural populations.

For example, hospitals may receive payment adjustments based on serving a disproportionately large share of low-income Medicare and Medicaid patients. These disproportionate share hospitals (DSH) serve more low-income Medicare and Medicaid patients than patients with private insurance whose health plans pay much more. Supplemental payments for DSH hospitals are based on the percentage of low-income patients they treat and a hospital’s DSH percentage must be at least 15% to qualify. Medicare DSH payments account for 3.3% of inpatient payments.21

Additionally, hospitals that qualify for Medicare DSH may also qualify for uncompensated care payments. These payments reimburse 75% of what would’ve been paid for a Medicare DSH payment for uninsured patients, based on the number of days spent in the hospital.22 These payments will amount to $5.8 billion in 2024.23

Rural Hospitals

Medicare also has a number of designations for rural hospitals which come with higher payments. The purpose of these benefits is to keep rural hospitals open and financially viable. Below are the seven types of rural hospital designations in Medicare:

- Critical Access Hospitals are exempt from the prospective payment system and instead receive 101% of their “reasonable” costs, determined by a Medicare formula.24 They must be in a rural area and have no more than 25 beds.

- Medicare-Dependent Hospitals are paid 75% of the difference between the Medicare rate and hospital-specific rate, which are usually higher. Medicare patients must account for at least 60% of their inpatient days or patient stays and have 100 beds or less.25

- Sole Community Hospitals are paid more for inpatient care under a hospital-specific rate and for outpatient rates by a 7.1% bump.26 These hospitals must be at least 35 miles from another hospital and have fewer than 50 beds, among other requirements.27

- Low-Volume Hospitals may receive up to an additional 25% for every discharge of a Medicare patient. Hospitals qualify for this designation by seeing less than 3,800 patients in the previous year and being more than 15 miles from the nearest inpatient hospital.28

- Rural Emergency Hospital is the newest designation for rural hospitals, created in December 2020. These hospitals must have fewer than 50 beds and receive an additional 5% for outpatient services. Critical Access Hospitals may also qualify to convert to a Rural Emergency Hospital.29

- Rural Referral Centers are rural hospitals that receive referrals from surrounding hospitals. These hospitals may also qualify as sole community or Medicare-dependent hospitals. They are not required to be located in rural areas.

- Disproportionate Share Hospitals can include rural hospitals on top of the of their other benefits.

Other Payments

Medicare pays some hospitals extra in other ways:

- Graduate Medical Education: Since Medicare’s creation in 1965, the program has paid teaching hospitals for medical residency training programs. These payments include direct costs (like residents’ salaries) and indirect costs accounting for increased patient care as a result of resident training. In 1997, Congress capped the number of Medicare-funded residencies to control costs.30

- Alternative Payment Models: Through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Innovation Center, Medicare develops alternative payment models separate from the traditional fee-for-service payment system. These models look to pay hospitals and physicians more efficiently by reimbursing based on costs and quality, as opposed to the number of services. They also aim to make providers more accountable for patient outcomes.

- Bad Debt Reimbursement: Medicare reimburses hospitals for unpaid out-of-pocket expenses owed by Medicare patients to hospitals, bad debt, at 65%.31

Funding Stream 2: How Medicaid and CHIP pay hospitals.

While Medicare is administered by the federal government alone, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are administered by the states.

Medicaid

Federal spending on Medicaid accounts for 70% of program spending.32 The federal portion of Medicaid financing is based on the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) formula. This funding ranges from 61.1% – 85.7% for traditional Medicaid and is set at 90% for the population under the ACA Medicaid expansion.33 States are responsible for financing the remaining portion.

Most states enroll Medicaid beneficiaries in managed care health plans, which cover all Medicaid benefits.34 The remainder are in fee-for-service, where Medicaid pays providers directly.

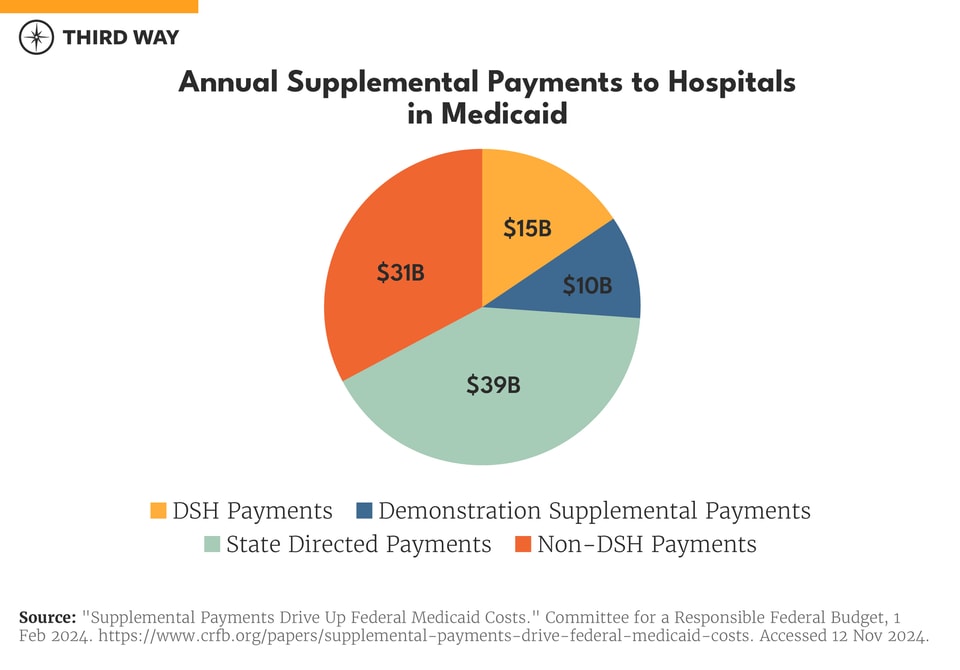

On top of managed care and fee-for-service payments, Medicaid gives hospitals a number of supplemental payments. First, like Medicare, Medicaid has its own designation for disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments with their own qualifications. States have flexibility in determining which hospitals qualify for DSH and how much they qualify for. Federal funding for DSH payments is capped for individual states based on 1992 spending.35 Medicaid DSH payments account for 17% of Medicaid’s payments to hospitals.36 As part of the Affordable Care Act, Congress scaled down payments through Medicaid DSH payments. However, these cuts continue to be delayed by Congress.

Outside of DSH funding, there are a number of supplemental payments to increase Medicaid’s reimbursement of hospitals. Together, these supplemental payments exceed DSH payments.37 One is through upper payment limits. This increases the Medicaid base rate based on what Medicare pays for medical services. Medicaid also pays hospitals for graduate medical education. Further, Medicaid reimburses hospitals for uncompensated care.38 While these payments come from Medicaid itself, states also increase payments to managed care organizations through “state directed payments,” which then flow to hospitals and other providers.39

States also employ financing mechanisms to increase provider payments, while decreasing the state’s spending on the program. States do this by imposing taxes on providers to help generate revenue for the Medicaid program, then using these funds to increase payments to those same providers. In effect, this increases Medicaid spending by the federal government while reducing the state’s share of Medicaid spending. There is currently a “safe harbor” threshold of 6% preventing excessive financial gaming of these provider taxes.

CHIP

Like Medicaid, CHIP is jointly funded by the federal government and the states. However, the federal government’s share of CHIP spending is higher than Medicaid. While Medicaid does provide coverage for low-income children, the income thresholds for CHIP are higher than Medicaid.

The myth of payment inadequacy

The hospital industry has spread the myth that Medicare and Medicaid payments are inadequate so they can ask for higher federal payments and justify their high prices in the commercial market. However, according to at least one of several accounting systems, just more than half of hospitals make money on Medicare, and about a third make money on Medicaid.40

While Medicaid rates are generally lower than Medicare, the number of supplemental payments made by Medicaid programs closes the gap between the two programs for the average hospital.41

Funding Stream 3: How the tax code benefits hospitals.

Many hospitals enjoy large benefits through the tax code. Nearly half of US hospitals are not-for-profit, giving them significant federal, state, and local tax exemptions.42 In 2021, the tax exemptions for nonprofit hospitals amounted to $37.4 billion.43 Over the next decade, federal tax exemptions are projected to cost the federal government $260 billion.44

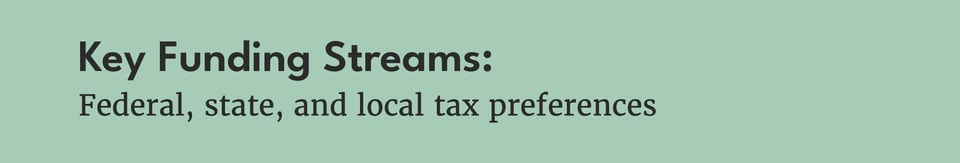

As a condition of these tax benefits, the IRS requires nonprofit hospitals to provide community benefits including financial assistance policies for charity care.45 However, nonprofit hospitals provide less in charity compared to their for-profit counterparts.46 The IRS required nonprofit hospitals to provide charity or discounted care to the best of their ability before the Tax Reform Act of 1969 broadened what types of benefits they may provide to satisfy community benefit requirements.47 The top community benefit reported by nonprofit hospitals at 44% of reported claims is “unreimbursed Medicaid costs.”48

Despite these generous tax advantages, nonprofit hospitals provide just 2.3% of their revenues towards charity care, while for-profit hospitals provide 2.8% and government-run hospitals provide 4.1%.49 As mentioned previously, nonprofit hospitals may also receive additional funding from Medicare and Medicaid disproportionate share funding as well as benefits from drug manufacturers through the 340B Drug Pricing Program.

Funding Stream 4: How the private sector pays hospitals.

While Medicare and Medicaid are the largest individual programs that pay for hospital care, employers and private commercial plans account for more than two-thirds of hospitals’ revenue.50 Most Americans have private health insurance, most commonly through their employers. Unlike public programs like Medicare and Medicaid who set their reimbursement rates, private health insurers individually negotiate prices with hospitals to form their networks.

The federal government subsidizes private health insurance in two ways: the tax exclusion on employer-sponsored insurance, and the Affordable Care Act marketplace. Nearly 165 million Americans are covered through their job, and employer and employee spending on health care benefits is exempt from taxes.

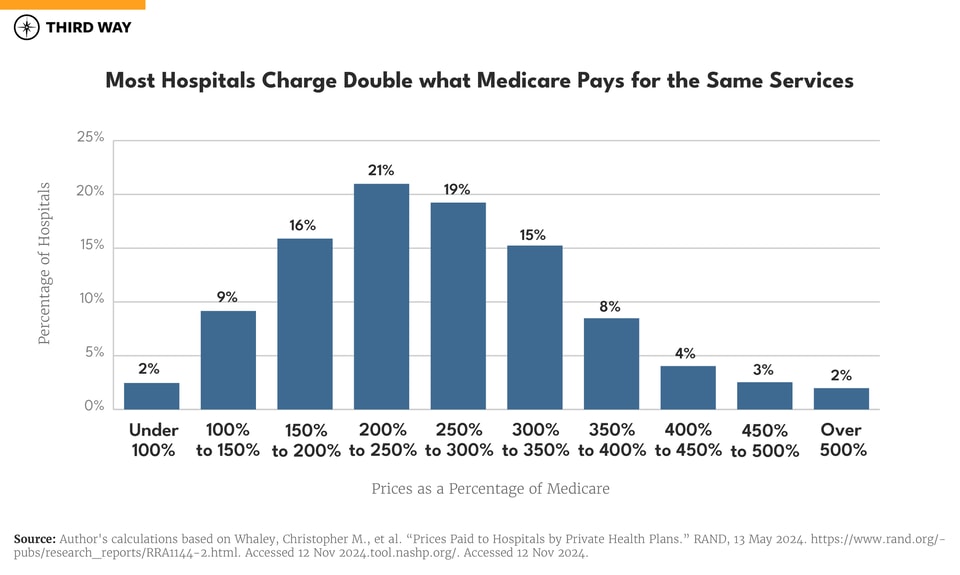

Patients with private health insurance pay hospitals significantly more than Medicare. On average, the private sector pays hospitals 254% of what Medicare pays for the same services.51 Because health care spending by employers is tax-exempt and the federal government subsidizes private insurance through the Affordable Care Act, higher prices for hospital care in the private market mean more in federal budget spending.

Consolidation increases the prices patients pay for hospital care.

The prices paid to hospitals by private health plans are determined by individual network negotiations between the two parties. In order to gain higher payments from private plans, hospitals often look to increase their market power through mergers and acquisitions. Larger hospital systems that have more market power can negotiate higher rates with health plans, increasing prices for hospital care. Three-quarters of hospital markets are highly consolidated, and hospitals are acquiring physician practices to convert them into hospital outpatient departments, which charge higher prices.52 On average, hospitals charge 8.3% more in concentrated markets.53 Hospital acquisition of physician practices increases prices by 14% on average, and hospitals add on facility fees to increase charges.54

According to one recent study, price increases hurt wage growth and increase unemployment because rising hospital prices mean employers need to pay higher premiums. As a result, they must reduce spending elsewhere by limiting wage increases for their employees and, in some cases, reducing the number of workers they employ.55

The 340B Drug Discount Program

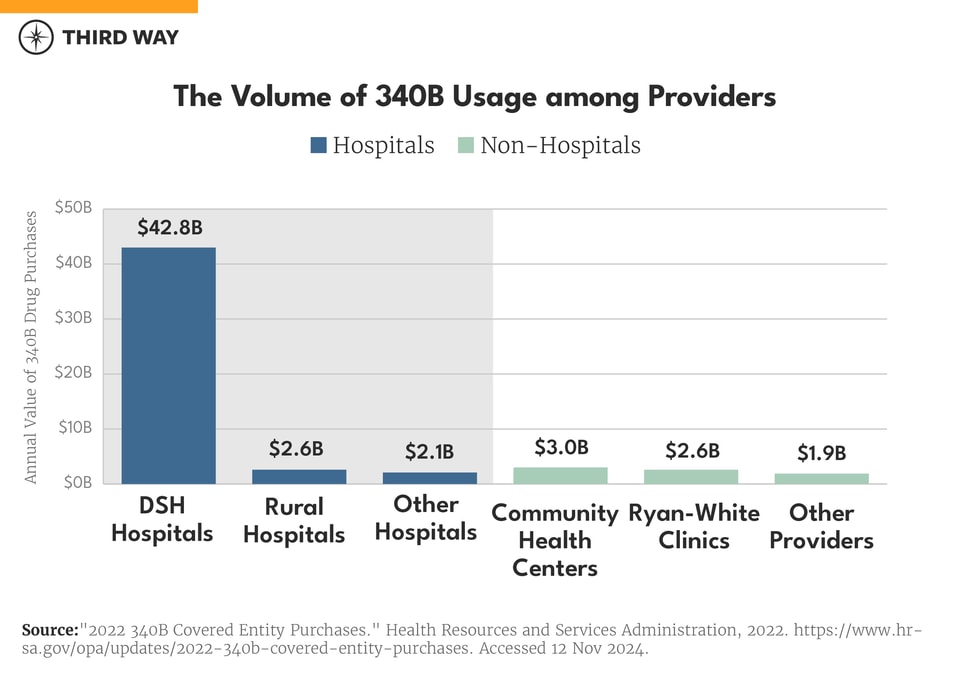

As a requirement for prescription drugs to be covered by Medicare and Medicaid, the federal government requires drug manufacturers to provide steep discounts to certain types of hospitals and medical providers. This happens through the 340B Drug Pricing Program.

Hospitals purchase discounted drugs and then get reimbursed by patients’ health plans at the full price, allowing them to keep the difference. The types of hospitals eligible for the program must be not-for-profit and designated as a Medicaid DSH hospital, critical access hospital, children’s hospital, free standing cancer hospital, rural referral center, or sole community hospital.56

The 340B Drug Pricing Program affects hospital prices in two ways. First, the price hospitals charge for physician-administered drugs have higher markups under 340B compared to non-340B hospitals.57 This is because hospitals have an incentive to charge more to keep a larger discount spread. Second, 340B hospitals want to acquire physician practices so those clinics may capture discounts as well. This allows hospitals to have more patients prescribed discounted drugs and charge higher prices for other outpatient services.

Conclusion

Health care is the largest source of spending in the federal budget, and hospitals are the single largest category within that. Growth in federal spending continues to be a pressing concern, as is the need to address rising hospital costs. Despite claims of underpayments from public programs, many hospitals are doing just fine—especially when accounting for the multitude of supplemental programs that exist to boost hospital payments.

What’s clear from the multitude of payments and funding sources is that the hospital financing system in this country is in need of reform. With an understanding of how hospitals get paid, policymakers can work to lower prices, increase competition, and improve financial stability for hospitals across the country and especially in truly low-income and rural communities.