Report Published November 14, 2023 · 15 minute read

Fixing a Critical Safety Net Program: 340B

Darbin Wofford & David Kendall

Takeaways

The 340B Drug Pricing Program is an essential tool for uninsured and low-income patients to access lifesaving medicines. The program, which requires drug manufacturers to provide discounted medicines to qualified providers, can help patients access cheaper medicines that would otherwise be unobtainable.

However, the 340B program is not delivering lower costs to all the patients it should be. There is nothing preventing discounts from being converted into hospital profits or diverted to care in wealthier and more profitable areas.

This brief explores how the 340B program works, unpacks problems embedded within the current structure, and offers a new solution to make 340B a patient-centered program—ensuring individuals benefit rather than profitable hospital systems.

Richmond Community Hospital, a struggling facility in a predominantly Black neighborhood, had to close its intensive care unit in 2017. The hospital is under the ownership of Bon Secours Mercy Health, one of the most profitable hospital chains in Virginia. Why is Richmond Community struggling while its parent company generates $100 million in profits every year? Look no further than the cryptically named 340B program.

Bon Secours uses Richmond Community to purchase cheaper, discounted drugs through the 340B Drug Pricing Program and spends the savings on its other hospitals in wealthier, often whiter neighborhoods—while cutting services at Richmond Community. One doctor from Richmond Community noted “Bon Secours was basically laundering money through its poor hospital to its wealthy outposts.”1

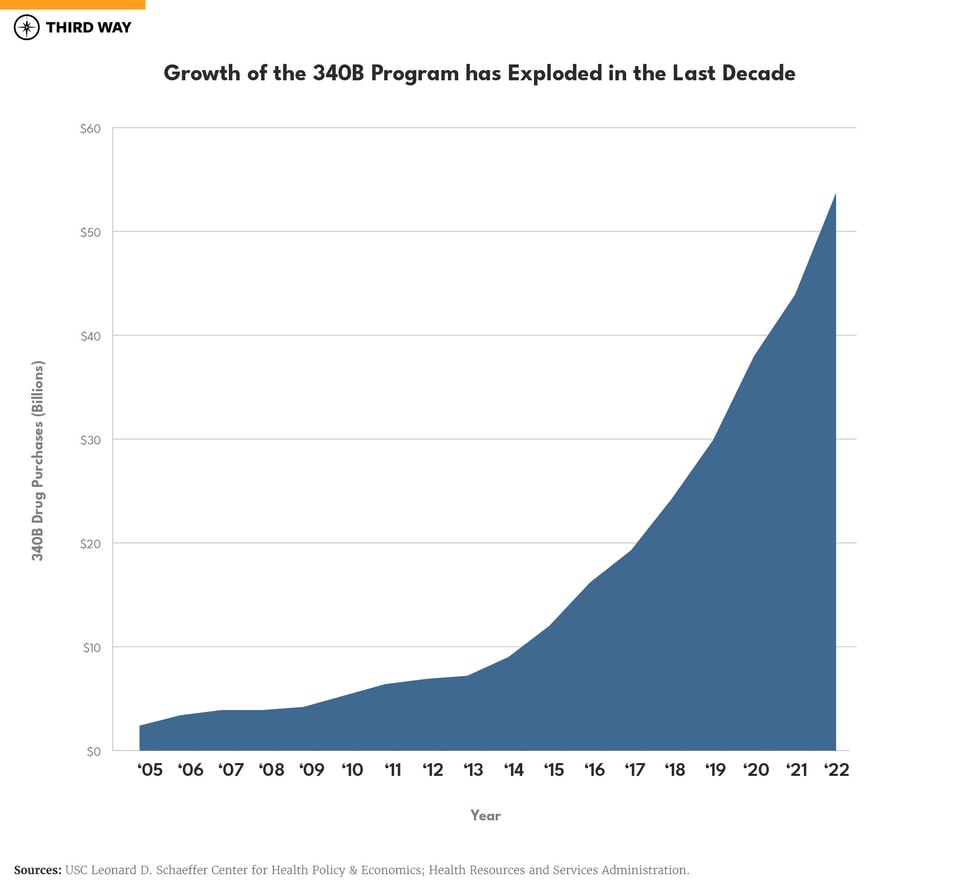

The 340B program requires pharmaceutical manufacturers, as a condition of having their outpatient drugs covered under Medicaid and Medicare Part B, to sell these drugs at discounted prices to designated hospitals, clinics, and community health centers.2 Today, the 340B program accounts for $53.7 billion in annual discounted sales, a rapid increase from just $2.4 billion in 2005.3 The program is the second largest federal prescription drug program with more spending than Medicaid and Medicare Part B and lower than Medicare Part D.

340B discounts were originally intended to provide additional resources to low-income communities. Providers keep the “spread” of the discount, the difference between what the providers pay with the discounted price and the full amount reimbursed by public and private health plans. However, this creates a financial opportunity for hospitals to maximize the number of discounts they receive for their patients without necessarily providing benefits to vulnerable patients.

Below, we explore how the 340B program works, including how funding flows from manufacturers to health care providers. We also break down the unintended consequences in the program’s design, including how discounts encourage padding profits over expanding access to care in vulnerable communities. Finally, we offer a new solution where profits from 340B drug discounts follow patients, not hospitals.

This report is part of a series called Fixing America’s Broken Hospitals, which seeks to explore and modernize a foundation of our health care system. A raft of structural issues, including lack of competition, misaligned incentives, and outdated safety net policies, have led to unsustainable practices. The result is too many instances of hospitals charging unchecked prices, using questionable billing and aggressive debt collection practices, abusing public programs, and failing to identify and serve community needs. Our work will shed light on issues facing hospitals and advance proposals so they can have a financially and socially sustainable future.

What is 340B?

The 340B Drug Pricing Program was created in the early 1990s to deliver discounts on outpatient drugs to certain safety net health care providers serving large numbers of low-income and vulnerable patients. Here are the basics of the program:

- Covered Providers: The 340B program requires manufacturers to provide discounts on outpatient drugs to certain providers, the legal term being “covered entities.” These providers include black lung and HIV/AIDS clinics, community health centers, state or county hospitals, and private, nonprofit hospitals.4 Hospitals in the program are typically disproportionate share hospitals (DSH), which provide a larger portion of care to patients enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, and patients without insurance.5

- Qualified patients: Patients who qualify for 340B discounts include any patient of a covered provider with whom they have an established relationship regardless of the patient’s income.

- Incentive to Participate: Manufacturers who want their outpatient drugs covered under the Medicaid and Medicare Part B programs must also participate in 340B by providing mandated discounts—a huge incentive to join the program.

- Discount Size: Discounts range on average from 25-50% depending on the type of drug, the price, and how much the price has risen over the rate of inflation.6

- Discount Use: 340B providers receiving federal grants, such as community health centers, are required to use the spread from the 340B discounts for the benefit of their patients. For example, community health centers charge less to lower-income patients and offer them additional services like dental care, which are not available elsewhere.7 However, 340B hospitals do not have such requirements. Hospitals are allowed to use the spread from these discounts as they see fit, which typically does not include sharing discounts with low-income and vulnerable patients. 340B providers can get discounts on patients regardless of income—rich or poor—as long as there is a pre-existing relationship between the patient and provider.

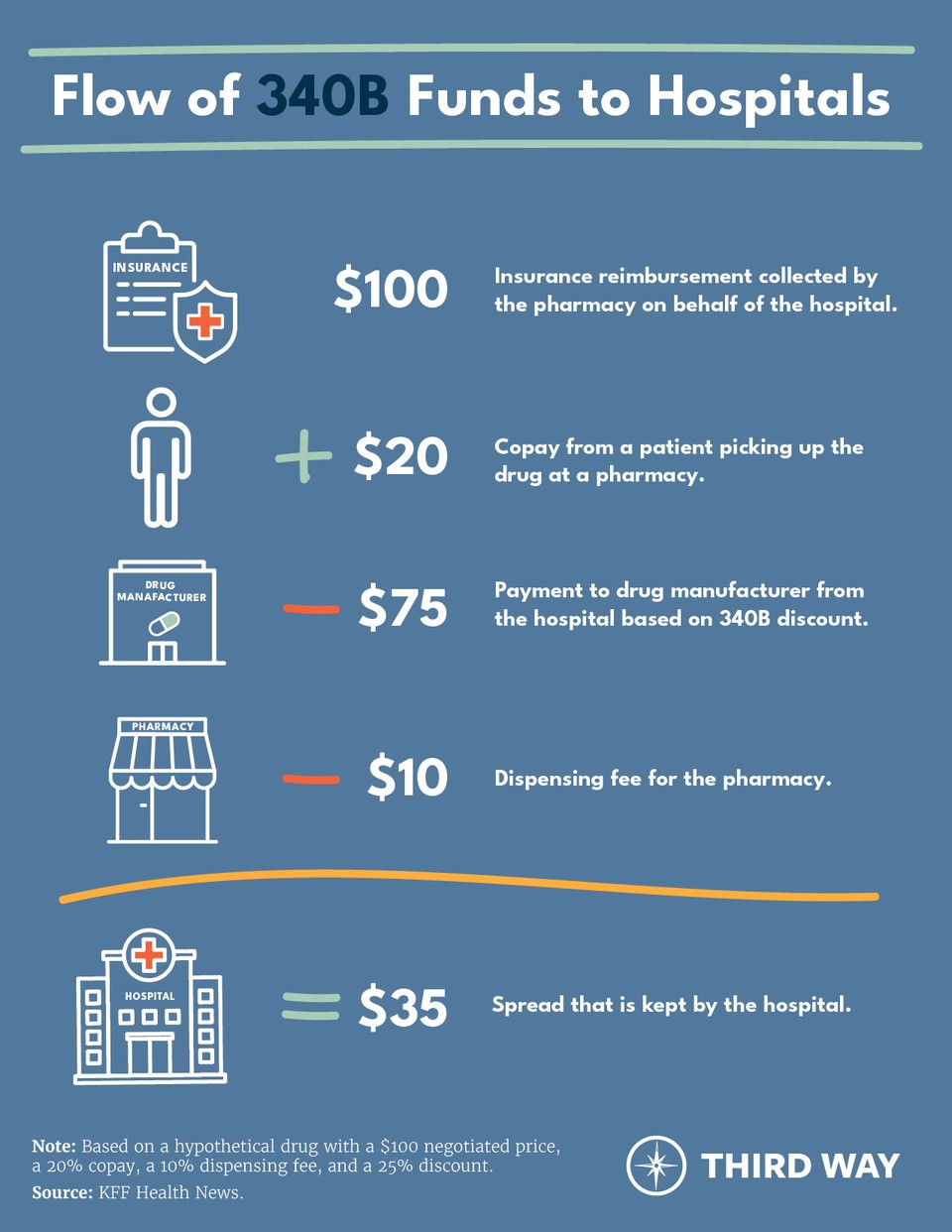

Funding flows from the manufacturer to the health care provider through the following six simplified steps:

- Prescription: A medical professional at a 340B provider prescribes or administers medication to a patient.

- Covered Provider Purchase: The provider purchases the drug at a discount from the manufacturer, which ships it to the pharmacy.

- Patient Purchase: The patient takes their prescription to a pharmacy to collect the medicine, paying their cost-sharing portion to the pharmacy or the full list price if uninsured.

- Insurance Pays Pharmacy: If the patient has coverage, either through private insurance or Medicare, their health plan will reimburse the pharmacy at the full negotiated price for the prescription.

- Pharmacy Pays Provider: The pharmacy then distributes the reimbursed funds to the provider and keeps a portion as a dispensing fee.

- Provider Keeps Discount: Finally, the provider now keeps the difference between the discounted acquisition price of the drug and the total reimbursement amount, minus the pharmacy dispensing fee. As noted above, this is called the “spread.”

The graphic below illustrates an example of how 340B funding flows to hospitals.

The Problem: Inadequate Assistance for Vulnerable Patients

The 340B Drug Pricing Program is failing to deliver lower costs for patients in vulnerable communities. Ideally, savings from the program would be reinvested to provide more and better care to the vulnerable populations these providers are supposed to serve. However, there is nothing preventing discounts from being converted into profits or redirected to other locations within the system the hospital is part of, as in the case of Richmond Community. Pharmacies contracted to dispense 340B-discounted drugs on behalf of covered entities are expanding into wealthier and less diverse areas. Furthermore, the growing trend of hospital consolidation and acquisitions to capture 340B discounts raises costs and reduces access to care for vulnerable patients.

“The idea is that in getting drugs for low cost or nearly for free, they [providers] can and should pass along the savings to these patients in the form of free or nearly free healthcare. When we evaluate the facts, we see where bad actors have taken a well-intended government program and created unintended negative consequences.” – Reverend Al Sharpton8

Discounts encourage padding profits over expanding care.

340B providers are not only allowed to purchase drugs with the average 25-50% discount, but they may also charge the patient’s insurance—whether it be private insurance or Medicare—what the drug would’ve cost without the discount. Yet patients must pay the full cost-sharing amount for the drug determined by their coverage. If the patient has not yet met their deductible or lacks coverage, hospitals often charge these patients for the total undiscounted charges for the drug. And if a patient does not have health insurance, they often receive a bill from the hospital for the hospital’s full charges for the drug. With no requirement that patients benefit from the 340B discounts in most cases, only 340B providers benefit from the flow of these discounts.

In Medicare Part B, outpatient drugs are generally reimbursed at 106% of the average sales price, despite 340B hospitals receiving an average 25-50% discount on the acquisition cost of the drug through the 340B program. Together, Medicare and beneficiaries are responsible for paying the full reimbursement amount for the drug (i.e., generally 106% of average sales price). Beneficiaries pay up to their deductible (if it has not already been satisfied) plus 20% of the reimbursement amount through Medicare’s coinsurance. The rest comes from Medicare Part B. Because 340B hospitals are not required to extend discounted prices on 340B-eligible drugs to their patients, beneficiaries and taxpayers often pay the full cost of the drug.9 For 340B drugs in Medicare Part D, payments made by Part D drug plans work like they do with private insurance.

Between 2018 and 2022, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) attempted to address Medicare’s overpayments for 340B drugs by decreasing reimbursements from 106% to 77.5%. But the Supreme Court reversed those cuts after finding CMS failed to adhere to procedural requirements before instituting these reductions.

Moreover, the 340B program drives up the use of drugs, especially those that are high-priced. A Government Accountability Office study found that prescription drug spending in Medicare Part B was “substantially higher” at 340B disproportionate share hospitals compared to non-340B hospitals.10 The report found that patients at these hospitals are either prescribed more drugs or higher-priced drugs. The 340B program is intended to help low-income, vulnerable patients and operates in a way that drives up costs for patients because warped incentives encourage hospitals to prescribe more and higher priced drugs to capture the spread. Additionally, one study found that 69% of 340B disproportionate share hospitals provide less charity care than the national average.11 Meanwhile, the program is not helping to improve the quality of treatment of low-income and other vulnerable groups, as one study found for patients with asthma.12

Pharmacies for 340B are expanding into wealthier and less diverse areas.

After a patient receives a prescription from their 340B provider, they might take the prescription to a retail pharmacy contracted with the provider to dispense 340B drugs, often called a contract pharmacy. Following the pharmacy receiving reimbursement for a 340B-discounted prescription acquired by a provider, the pharmacy provides the reimbursement amount to the 340B provider, minus a cut for the pharmacy in the form of a dispensing fee.

Before 2010, 340B providers were only permitted to contract with a single pharmacy if they lacked an on-site location for dispensing prescriptions. However, the Department of Health and Human Services issued guidance in 2010 reversing that longstanding policy.13 This allowed for 340B providers to contract with as many pharmacies as they like. Since 2010, the number of contract pharmacies increased from fewer than 1,300 to more than 30,000 in 2023.14

As the number of contract pharmacies has grown, vulnerable communities are often left out. That’s because contract pharmacies are often located in wealthier and less diverse areas.15 The presence of contract pharmacies in wealthier areas contradicts the intention of the 340B program: to help vulnerable communities. Furthermore, a GAO report found only around 50% of contract pharmacies pass along discounts to patients at their contract pharmacies.16

In January 2023, the US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ruled in a dispute between drug manufacturers and the federal government that manufacturers are not required to ship 340B-discounted drugs to an unlimited number of pharmacies contracted with 340B providers. However, two other federal circuit courts are expected to decide similar cases involving other manufacturers.17

Consolidation is rampant within 340B, leading to higher prices.

Due to the high profit margins associated with 340B discounts, hospitals are incentivized to extend their reach. This may occur in one of two ways.

First, like Richmond Community Hospital, large health care delivery systems may acquire 340B hospitals and take advantage of the discounts while cutting services to the patients they serve and redirecting those funds to expand access in wealthier communities where more patients may be insured.18 This incentive for consolidation fuels hospital acquisitions, translating into overall higher costs across the health care system.19

Second, hospitals may acquire clinics and register them under the 340B program, sometimes called “child sites.” For example, 340B hospitals may acquire providers such as cancer practices to expand their margins without demonstrating any benefits for low-income patients.20 These child sites are permitted to receive 340B discounts on prescriptions dispensed or administered to eligible patients, however these sites are often located in higher-income and less diverse areas.21 This allows the spread from 340B to flow into affluent communities.22 Hospital acquisition of physician practices also leads to an average price increase of 14%.23

The Solution: A Patient-Centered 340B Program

The 340B program is an essential tool for uninsured and vulnerable patients to access lifesaving medicines. But program discounts should improve patient access and lower costs—not pad hospital profits and incentivize further consolidation in the health care system.

To address these issues, policymakers should reform the 340B program to include accountability to patients so they benefit rather than profitable hospitals. A good illustration of this can be found with community health centers that provide care to vulnerable populations. They rely on the 340B program to maintain their operations and pass discounts onto their patients through lower prices and free care. The community health centers are a prime model for how all 340B providers should operate: through a patient-centered 340B program. This kind of accountability would be sufficient to exempt existing safety net providers including community health centers, rural hospitals, and safety net hospitals from changes to 340B.

Reforming 340B program would require three structural changes:

First, ensure patients benefit from the discounted drugs. Patients must be front and center of any meaningful reform to 340B. Low-income and uninsured patients should receive discounts when they purchase their prescription at the pharmacy counter.

Patients must be front and center of any meaningful reform to 340B.

When an insured patient purchases their prescription at the pharmacy counter, a percentage of the discount should be directly applied to their total cost-sharing. Specifically, Congress should require 340B hospitals to distribute discounts to patients on a sliding scale based on patients’ income. Of note, other 340B providers (like federally qualified community health clinics) already have that requirement. Congress should also require that financial benefits from 340B discounts stay within the site of service when the discount is provided to a hospital. This would ensure gains from the program serve the patients in those communities.

Second, reform Medicare’s reimbursement for 340B drugs. Medicare should not overpay hospitals for 340B-discounted drugs. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services attempted to lower Medicare’s reimbursement for outpatient Part B drugs from 106% of the average sales price to 77.5% of the average sales price; however, the Supreme Court overturned this adjustment on procedural grounds. The Administration should again lower Medicare’s reimbursement for 340B drugs through Part B—and use the correct administrative procedures the government must follow under the Medicare statute. This would save taxpayers $1.6 billion annually and lower costs for Medicare beneficiaries.24 Addressing Medicare’s reimbursement for 340B drugs would limit hospital incentives for prescribing more or higher-cost drugs that increase costs for patients and the taxpayer. Rural and safety net hospitals would be exempt from these adjustments to preserve access to hospital care for those communities.

Reducing Medicare’s payment for discounted drugs would decrease the spread 340B hospitals generate with respect to outpatient drugs prescribed to Medicare Part B beneficiaries. These savings to Medicare should be reinvested into hospitals that need it most. In an accompanying report, we will propose to improve targeting for safety net hospitals that provide essential care to America’s vulnerable populations, closing coverage gaps leading to larger amounts of uncompensated care, and investing in our health care workforce.

Third, require hospitals’ off-site clinics and contract pharmacies to meet a 340B standard. Congress should require outpatient clinics and pharmacies owned by or contracted with 340B providers to meet enforceable standards for being part of the program, such as serving vulnerable populations or being located in medically underserved or rural areas. For providers that do not have access to nearby pharmacies that fit those standards, additional contract pharmacies should be permitted. For example, if a 340B provider is in an area with no pharmacies reasonably nearby, it may request to contract with a pharmacy outside of their geographical area.

Conclusion

The purpose of the 340B program is to improve patients’ access to affordable medicines; however, that has not been the case. The reforms listed above would vastly improve the program by lowering costs for patients, decreasing incentives for further consolidation, and preventing the program from being a piggy bank for large hospital and pharmacy systems.

In addition to policies such as site-neutral payments reducing high prices in hospital outpatient departments compared to physician offices and bolstering competition in the health care system, reforming 340B is another step in achieving the ultimate goal of lowering out-of-pocket costs for patients and reducing perverse incentives for consolidation.