Report Published June 15, 2022 · 11 minute read

Preventive Care: How Do We Know What Works?

Jacqueline Garry Lampert & David Kendall

Ben Franklin famously wrote “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” in support of fire prevention.1 Fire, then as now, is an obvious threat, and fire prevention provides immediate benefits. Preventing disease is far less obvious, however, and requires scientific studies of patients over long periods. Evaluating the science behind prevention is the special responsibility of a small group of volunteers who make up the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF or ‘Task Force’). They grade the evidence on the effectiveness of preventive services that providers deliver. The grades then determine which services get covered at no cost to patients. Even though the work of the USPSTF is often behind the scenes and not well known in Washington, its recommendations have become increasingly important to the health of everyone in the United States. In this report, we explain how USPSTF works, who uses their ratings, and challenges they face. We also propose three ways for Congress to improve the work of the Task Force: 1) double the USPSTF budget to increase their capacity to evaluate an expanding set of services; 2) direct the Task Force to prioritize the evidence gaps it uncovers and identify how such gaps should be addressed; and 3) stop paying for preventive care that the Task Force recommends against.

What is the USPSTF?

The USPSTF is an all-volunteer panel of 16 nationally-recognized experts in prevention, evidence-based medicine, and primary care.2Established in 1984, the Task Force’s mission is “to improve the health of people nationwide by making evidence-based recommendations about clinical preventive services and health promotion.”3 Members are appointed to four-year terms by the Director of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). While AHRQ is authorized by Congress to convene and support the Task Force, the Task Force itself is an independent, nongovernmental entity.4

How does the USPSTF work?

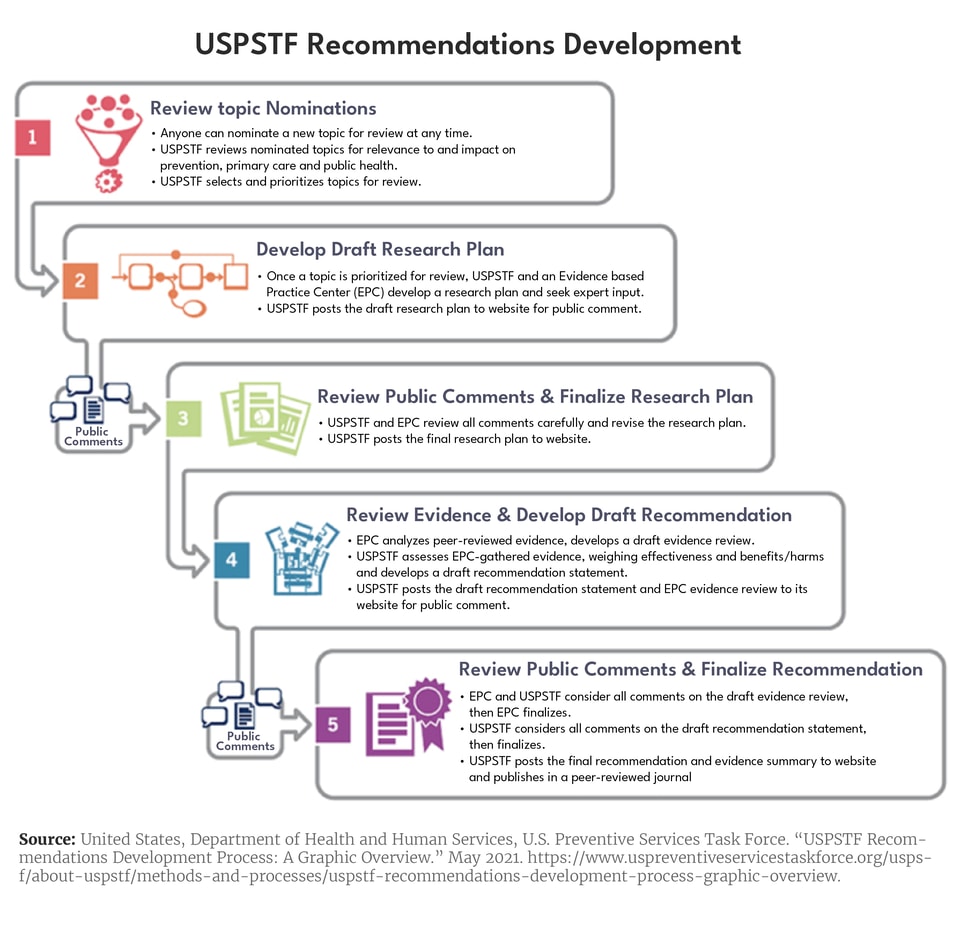

The Task Force uses a five-step process to develop recommendations regarding the effectiveness of clinical primary and secondary preventive services offered in a primary care setting.5Because recommendations focus on disease prevention, they apply only to individuals before symptoms occur. An overview of the recommendation development process, which takes three years on average, is provided in Figure 1.6The Task Force aims to update recommendations every five years, but is not always able to achieve this goal. In addition, the Task Force outlines a process for consideration of an early topic update due to the availability of new evidence.7

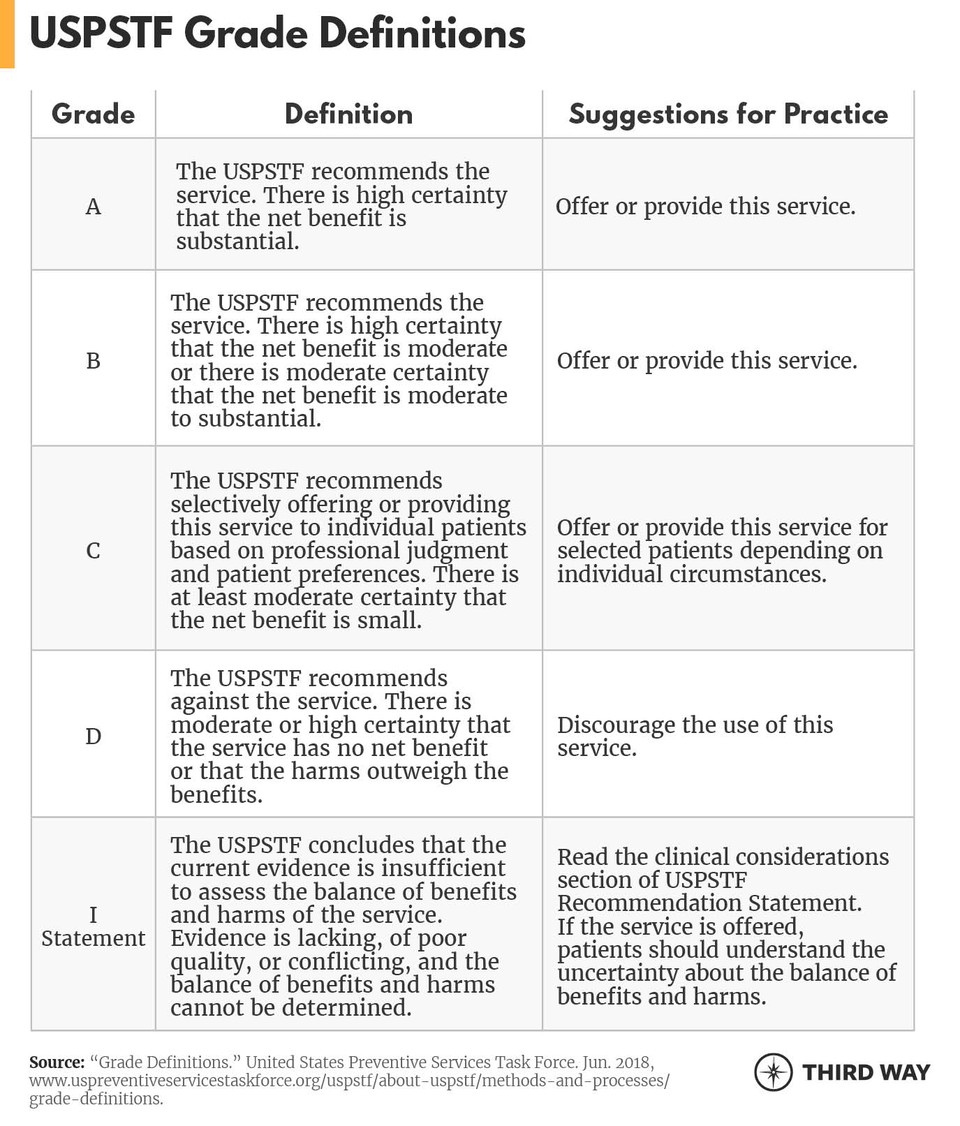

A key part of the Task Force’s process involves assessing the research on a particular topic (which is posted publicly), and determining where sufficient, high-quality evidence exists as well as where it does not. Recommendations are entirely based on the strength of the evidence and the “balance of benefits and harms of a preventive service.”8 The Task Force’s recommendations are distilled to a letter grade or an “I Statement” (indicating that insufficient evidence exists) as shown in Figure 2.9The assigned grade reflects the net benefit or harm of the service as well as the strength of the evidence, as defined in the chart below. For example, the Task Force gives screening for high blood pressure in all adults an “A” grade.10

It is not uncommon for the Task Force to determine that insufficient evidence exists to support a recommendation. In fact, 53 of the 86 recommendations issued by the Task Force have I Statements either for the service in general or for a specific patient subpopulation.11In both I Statements and letter recommendations, as well as in an annual report to Congress, the USPSTF identifies evidence gaps or research needs. However, these descriptions are not always specific and actionable and may not lead to the development of evidence that meets USPSTF’s inclusion criteria.12In addition, the Task Force does not have the resources or a framework to prioritize research gaps and describe the types of studies required to fill them.

Who uses the USPSTF ratings?

Congress has designated USPSTF recommendations for coverage requirements, which apply to private and public payers.13After many successful Task Force evaluations of evidence since its start in 1984, Congress included in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) a requirement that private health insurance plans (including those sold in the individual, small group, and large group markets) and self-insured plans governed by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) provide free coverage for all the preventive services that the Task Force rates “A” or “B.”14 The Internal Revenue Service subsequently clarified that high-deductible health plans may cover these services before the deductible is met.15The ACA also requires the waiver of beneficiary cost-sharing for "A" and "B" rated services covered by Medicare.16In addition, states that expanded Medicaid eligibility (as permitted by the ACA) are required to provide coverage of these preventive services without cost-sharing for the expansion population and enrollees in Alternative Benefit Plans, which some states use for setting benefits. In traditional Medicaid, states receive a one percentage point increase in the federal Medicaid match rate for preventive services provided without cost-sharing.17

USPSTF recommendations also inform the work of organizations such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance and others in their development of health care quality measures. Together, making preventive services free and measuring providers on their delivery of USPSTF-recommended preventive care has increased the use of preventive services so that today 231 million Americans have access to free prevention, which has increased the use of colon cancer screenings, vaccinations, contraception, and other services and reduced disparities across racial and other socioeconomic characteristics.18

More needs to be done to increase their use, although that challenge is outside the scope of the USPSTF. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused millions of Americans to skip or delay important health care, including preventive check-ups and screenings.19Moreover, in the years prior to 2020, just 50% of adults received preventive care recommended by the USPSTF.20

At the same time, not all preventive care is useful. Evidence sometimes reveals that a particular preventive service or screening does not offer a net benefit to patients and should not be used. For these interventions, the USPSTF also provides an invaluable service, systematically reviewing the evidence and recommending against their use. The ACA authorizes Medicare to exclude from coverage preventive services with a D rating from the USPSTF, but this authority has not been implemented.21

What challenges does the USPSTF face?

Science sometimes moves faster than the USPSTF can review and respond given current resources. This has serious implications for patient access to preventive screenings. Since the 1980s, when the USPSTF was established, medical knowledge has been growing rapidly.22 For example, the number of randomized clinical trials published each year has grown by 600% over this period.23 In the preventive health care space, new tools and services in development will make screenings more convenient for patients and may improve access to and utilization of preventive health care.

Since the 1980s, when the USPSTF was established, the number of randomized clinical trials published each year has grown by 600%.

Since the 1980s, when the USPSTF was established, the number of randomized clinical trials published each year has grown by 600%.

The Task Force’s budget in fiscal year (FY) 2022 was just $11,542,000, a level virtually unchanged since FY2012.24This level funding provides the Task Force with less purchasing power over time, reducing the number of evidence reviews the USPSTF can complete each year.25 Former Senator Max Baucus (D-MT) and former Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle (D-SD) have called for increased funding to help the Task Force expand its work.26The current funding level permits the Task Force to conduct evidence reviews and make recommendations on 10 to 12 topics per year and does not always permit timely review of recommendations in the face of compelling new evidence. For example, in 2014, the FDA approved the first human papillomavirus (HPV) test for primary screening for cervical cancer.27Shortly thereafter, the Society for Gynecologic Oncology and others issued interim guidance on use of the HPV test as primary screening, but the USPSTF recommendation was not updated until 2018, despite the test’s “equivalent or superior effectiveness” compared to cytology alone.28

This same problem may be on the horizon for colorectal cancer screening, which last saw its USPSTF recommendation updated in 2021. The Task Force typically reviews its recommendations every five years, so the colorectal cancer screening recommendation will be due for review in 2026. However, a blood-based screening test is likely to be available by 2023. This less invasive test could help close the colorectal cancer screening gap; about 30% of Americans are not up to date with the recommended types of screenings.29 While the Task Force details a process for considering an early topic update, it does not share the reasoning behind the decisions to take early action or not, and does not share the list of topics on its “review queue.”30Only the annual total number of requests from the public for reconsidering or updating topics is currently disclosed.31

Another challenge with updating guidelines is that the evidence base for equitable prevention is sorely lacking. As the Task Force has noted, participants in the clinical trials on prevention “have been predominantly white persons.”32 Nonetheless, the Task Force has developed a comprehensive plan for including equity in the development and dissemination of preventive measures.33

Finally, current payment incentives perpetuate the persistent use of services the Task Force has recommended against (a “D” rating). For example, since 1996, the USPSTF has recommended against routine screening for bacteriuria in asymptomatic, non-pregnant individuals.34 Yet a 2021 study found that Medicare paid for this test more than 14 million times annually (counting only office-based ambulatory care), resulting in nearly $170 million in annual spending. The testing can be harmful because it often leads to misdiagnosis as urinary tract infection and inappropriate antibiotic treatment, which in turn contributes to antibiotic overuse and the emergence of multidrug resistant organisms.35

Recommendations

Policymakers have been wise to utilize the Task Force’s work to increase access to evidence-based preventive care. Now they should increase investment in the Task Force while also more firmly implementing its recommendations.

First, Congress should double the Task Force’s $11.5 million budget. This will allow the USPSTF to expand its work on equity and accelerate its evidence review and recommendation processes to better keep pace with medical advancement. This is necessary to ensure timely, equitable patient access to highly-rated preventive services and to clearly identify preventive services with no benefit or insufficient evidence. Additional funding would also provide the Task Force with resources to show how it is responding to medical advancement by explaining its decisions on which topics to review or update early, including why topics were not chosen, and to disclose topics in the “review queue.”

Second, Congress should direct the Task Force to systematically describe and prioritize evidence gaps and specify the types of studies necessary to fill those gaps. A 2022 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine provides a series of recommendations that will help not only the Task Force but also researchers and funders identify the precise types of evidence that would fill gaps the Task Force identifies.36

Third, Congress should ensure that Medicare stops paying for preventive services the Task Force has assigned a “D” rating, which cause more harm than benefit. Ending this practice would readily pay for the increased investment in the Task Force called for above and provide additional funds for lawmakers to invest in other health care priorities. One 2021 study found that Medicare paid for just seven Grade D services 31.1 million times per year at a cost of more than $477 million.37 Despite having the authority under the ACA to end such payments, no administration has yet taken action. Congress needs to investigate why not or require the administration to do so.

Conclusion

The USPSTF provides an invaluable service by systematically reviewing evidence and recommending for or against the use of preventive services. In order to increase patient access to evidence-based preventive care that works, Congress must provide the Task Force with additional support to make timelier recommendations and prioritize evidence gaps to advance preventive health research. Congress must also stop paying for preventive care that the Task Force recommends against, both to protect patients and taxpayers.