Report Published July 1, 2015 · Updated July 1, 2015 · 17 minute read

Rethinking Career Pathways & Salary Structures for Teachers

Stephenie Johnson & Lanae Erickson

Takeaways

In order to recruit high-achieving young people to teach in our nation's classrooms, we must:

- Institute salary structures that pay and promote teachers for proven effectiveness;

- Create career ladders within the profession that offer the best teachers opportunities for greater responsibility, autonomy, and pay; and,

- Leverage private investment to pay for the transition costs of protecting veteran teachers while moving to new salary and promotion structures.

What was your first job fresh out of college? Are you still doing that exact same job today, carrying out identical tasks, receiving a similar salary? If not, you are not alone, as Americans today will have an average of 11 jobs over the course of their lives.1 Yet teachers remain in an antiquated rut, expected to maintain roughly the same level of responsibility, autonomy, and pay for the duration of their careers. If we are going to recruit the best and brightest Millennials to fill the 3 million open teaching positions our schools will have over the next decade, we have to rethink how teachers are promoted and paid as they advance through their careers.

The Problem

Teacher career pathways treat teachers like identical widgets.

Compensation structures ignore teacher performance and growth.

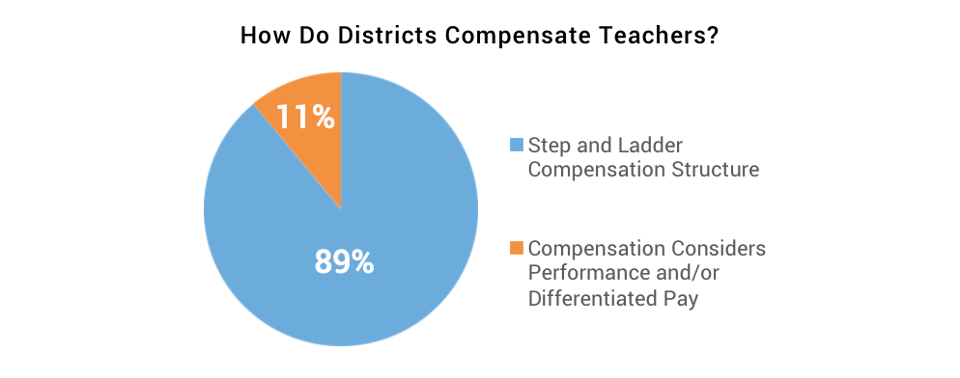

The majority of salary structures for teachers in this country disregard teacher performance in the classroom, as well as the time they spend out of the classroom helping other teachers develop their craft. In most circumstances, teachers are neither rewarded nor promoted based on their effectiveness as classroom educators or as teacher leaders. Instead, 89% of districts operate under a step-and-ladder salary schedule which offers pay increases only for the number of years spent in the classroom and additional higher education degrees.2 This means that many teachers only see a pay bump when they go back to school, which in many cases requires taking on more student loans. In fact, the average teacher holding a Master’s Degree in Education finishes with more than $50,000 in debt, nearly $8,000 more than their peers with MBAs.3 Not only does this outdated model make little financial sense for teachers, it makes little sense for districts, schools, and students given that studies show that there is no link between tacked-on teacher credentials and increased student achievement.4

This nonsensical pay-for-diploma system not only creates major problems for most teachers on the ground, but it also contributes to a public sense that the teaching profession is one that overlooks excellence. As evidenced in our most recent education poll, only 14% of voters think it is very likely for a teacher to be rewarded for excellent job performance, and a measly 10% think it is very likely for a teacher to get promoted for excellent job performance.5 So not only do we have an actual problem—teachers are still treated as indistinguishable widgets—we also have a perception problem.6 This negative image of the profession extends to the exact people we want filling our classrooms: high-achieving Millennials say that teaching is a profession for “average” people.7 A job that treats every person as an interchangeable cog clearly repels these young people who want their talent and hard work acknowledged, not ignored.8 Indeed, teacher turnover is highest among new teachers—a startling 40-50% leave teaching after just five years and the annual attrition rate for first-year teachers has increased by 40% over the past two decades.9 If we are going to recruit the best and brightest people into the classroom, we have to rethink how teachers are promoted and paid as they advance through their careers.

Promotion options do not allow teachers to stay in the classroom.

Simply put, a career in teaching is not compatible with a modern workforce. That’s because opportunities to climb a well-developed teaching career ladder—one with increased pay for excellent performance and additional responsibilities—are few and far between. This is in contrast to nearly every other 21st century professional, who is able to grow within their careers according to the quality of and dedication to their work. The majority of teachers who stay in the profession either plateau by staying in the classroom at the same level for years with the same set of responsibilities, or they choose to leave the classroom to become a school leader or district-level administrator. Even if they do not want to leave teaching, they may do so in order to fulfill their desire for an increase in pay, responsibility, and autonomy. Meaningful advancement opportunities for teachers who want to stay in the classroom and become leaders among their peers are rare. And even though we know that this is not the type of system ambitious and talented young people want to enter, these outdated structures continue to carry the day.

The expertise of master teachers is a wasted resource.

When teachers can’t train their peers and teach kids, valuable resources are lost.

The outdated system that most teachers operate under today simply does not allow the highest performing educators to share their expertise among their peers without sacrificing their passion for instruction. Instead, it is a system that fails to leverage the best teachers by allowing them to lead and mentor their co-workers in professional development part time while still delivering excellent instruction to kids for the majority of the school day. Expert classroom teachers themselves are hardly ever responsible for leading professional development, even though they know the challenges that their schools face more than any outside consultant. Instead, teacher training most often comes in the form of one-size-fits-all workshops, which the majority of teachers say don’t work and do very little to improve student achievement.10 The failure to give teachers the opportunity to lead within their schools and districts is an absolute waste of time and valuable human resources.

The majority of professional development funding for teachers is spent on programs that are ineffective.

Because the majority of teacher career ladder structures do not allow educators to both teach students and lead their peers, teachers who want to take on more responsibilities often leave the classroom. The result is not only bad for kids and disheartening for teachers, but it also explains why the majority of Title II Part A funds are used for teacher professional development activities—when expert teachers leave the classroom, more money must be spent training the new teachers who are hired to replace them.11 Those expert teachers do not lead these novice teachers in professional development because they have gone on to positions that require them to provide the functions of a principal or district-wide leader. So, not only do we have excellent teachers exiting the classroom, but new teachers come in who must be trained—an endeavor that costs up to $2.2 billion annually.12

Worse still, most teachers receive professional development that does not extend to support for implementation, which teachers need in order to be effective.13 In other words, once the workshop-style trainings are over, teachers do not receive any instruction about how to apply what they’ve learned in their own classrooms. As a result, professional development programs for teachers very rarely lead to positive effects on students’ academic proficiency.14 Not only do the majority of professional development programs waste teachers’ time, they also require expending valuable resources that could be redirected towards meaningful career ladder structures for teachers. What we need is a system that allows the most expert teachers to mentor and teach their peers in the application of newly learned practices through classroom observations and feedback—not more day-long seminars that have little connection to the classroom.

The Solution

Expand systems that promote & pay teachers like professionals.

Move to career ladder models that provide greater pay for more responsibility.

In our modern economy, we cannot attract high-achieving young people into the teaching profession by offering them outdated step-and-ladder pay structures. When asked what’s important to them in a job post-graduation, 91% of college students with a 3.3 GPA or higher said “opportunities to advance within the profession” were important, with 57% saying this was “very important,” and 89% said “salary for those established in the career” was important, with 52% saying that was “very important” (fewer said starting salary at the beginning of a career was as important).15 What teachers deserve, and what the Millennials we need to staff our classrooms want, is a career pathway that recognizes and rewards excellence with additional responsibilities, increased pay, and more autonomy. But at the same time, we should not ask teachers to abandon their classrooms and the students who inspire them in order to move up the ladder.

While it may seem difficult to implement a structure that honors both an expert teacher’s desire to teach his or her students and lead his or her peers, meaningful career ladders for teachers do exist that accomplish those goals—and they can be brought to scale. The Leadership Initiative For Teachers (LIFT) is just one example: the career ladder structure currently being implemented in District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS). LIFT is a career ladder with five-stages that provides high-performing teachers with opportunities to advance within the teaching profession through additional responsibilities, increased recognition, and better pay.16 IMPACTplus, developed by DCPS and the Washington Teachers Union, is the compensation system used in conjunction with LIFT.17 Teachers at the first two levels (“teacher” and “established teacher”) receive a normal base salary—a minimum of $54,975 with a Master's. That base salary increases substantially at each additional stage (“advanced teacher,” “distinguished teacher,” and “expert teacher”) if those teachers earn consistent effective and highly effective ratings.18 If they teach at high poverty schools, their increased earnings are even more substantial.19

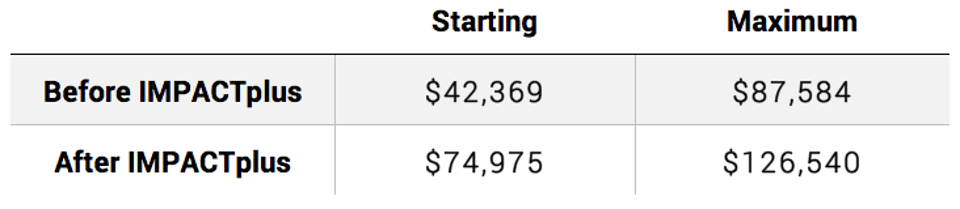

Under LIFT and IMPACTplus, a teacher who consistently earns “highly effective” observation ratings at a high-poverty school could possibly make up to $126,540 per year within nine years of teaching. Before the implementation of this system, the most a DCPS teacher could make was $87,584 per year—a pay out that wouldn’t be seen until after two decades of service. As teachers advance up the LIFT ladder, they also become eligible for a range of leadership opportunities, such as consulting teacher, instructional specialist, and master educator.20 And at no point are these teachers required to stop teaching in order to lead. To be sure, the most exceptional DCPS teachers are compensated at unprecedented and unparalleled levels, but this structure does not have to remain confined to urban areas like the District of Columbia. We have an opportunity now to expand meaningful career ladder structures like LIFT that challenge teachers to take on leadership roles and then recognize and reward them for doing so. Indeed, 85% of the high-achieving young people in our poll said opportunities to challenge themselves were either very or somewhat important when considering their career paths—but they also want to be recognized and rewarded for taking on those challenges.21 So if we want to recruit and retain the next generation of highly effective teachers, it is imperative that we prioritize the overhaul of outdated promotion and compensation systems.

Maximum Compensation in DCPS Before and After IMPACTplus22

Note: These compensation figures include the maximum amount of possible bonuses that can be earned through LIFT and IMPACTplus.

Continue and expand competitive grant programs to support and encourage this evolution.

The development of career ladder structures as a way to professionalize teaching and retain excellent teachers has received more serious attention since 2006, with the creation of the Teacher Incentive Fund (TIF)—a federal program that provides competitive grants to entities like districts and states to create and implement compensation structures for teachers that take student performance and classroom observations into account.23 Many of the recipients of these grants already have some sort of career ladder structure in place and use their awards to expand those existing systems. DCPS is one such recipient: in 2012, DCPS won a $62 million TIF grant to improve its teachers’ ratings on their evaluation scale, which has been in place since 2009.24 Evidence suggests that LIFT and IMPACTplus have improved the effectiveness of the DCPS teacher workforce, both through the attrition of low-performing teachers and the performance gains among those teachers who remained.25 One contributing factor to LIFT’s success is that it provides “exceptionally high-powered, individually-targeted incentives linked to performance as measured by multiple sources of data (rather than test scores alone).”26 Indeed, when incentives like increased pay and additional professional responsibilities are linked to multiple indicators of teacher performance, the teaching workforce overall improves.27 In order to continue successful programs like LIFT in the District of Columbia, bring other promising programs to scale, and gather more data on the effectiveness of different career ladder models, competitive grant programs like TIF must continue and expand.

Fund more career ladder programs by thinking outside the box.

Recruit private investors with the promise of federal matching funds.

Competitive grant programs can certainly continue to help localities expand their career ladder systems, but the relatively small number of grants given to these entities won’t be sufficient to overhaul the way most teachers are paid and promoted. On the other hand, we cannot expect the federal government to be the only source of money for this transition, especially in a system that lacks the infrastructure to navigate the necessary major financial changes. An alternative financing solution could require districts and states to work with private philanthropic entities to fund their career ladder models, with the federal government providing a one-time, 50% match of those private dollars. Charitable organizations including the Buffet Early Childhood Fund, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Pritzker Family Foundation are already investing billions of dollars in education. Increasingly, corporations are funding local education programs through their philanthropies, recognizing that investing in the education of today’s children is good for business down the line. And if we are serious about changing the future of public education, we must invest in the people who have the most in-school impact on students—public school teachers. Leveraging federal dollars to encourage an influx of non-governmental support for this transition could significantly speed progress.

Craft these innovative funding structures to pay for themselves over time.

Of course, there will be those potential investors and philanthropies skeptical of ever seeing an end to their contributions, worrying that the districts they fund will come to rely on them to push their model forward years later. Participation in this matching program, however, could first require localities to craft a plan for moving past the transition period and carrying out their programs in a self-sustaining way after the first few years. An applicant for the program could be asked to meet the same or similar requirements for those receiving TIF grants. In this way, the initial funding provided by investors would only be necessary for a short transition period as districts phase in changes to ensure current and veteran teachers aren’t punished. Once a career ladder program becomes self-sustaining, the stratification of teachers’ salaries—with few teachers making high earnings, few making low earnings, and the majority making the base salary amount—will render the funds initially used on transition costs unnecessary moving forward. What’s more, costs would eventually be off-set by increased retention among teachers—with less teachers leaving the profession, fewer teachers will need new-hire training, amounting to billions of dollars in savings that could be reinvested into the career ladder structure.

In addition to this leveling out of salaries over time, the federal Title II money that has been historically spent on outsourced workshop-style professional development could be redirected toward these payment and promotion structures. Indeed, the benefit of a career ladder model is that teachers are able to stay in the classroom part time while advancing in their career, receiving more money for taking on increased responsibilities outside of their own classroom. The increased responsibilities of the most expert teachers—those at the top of the career ladder— would include providing targeted professional development, such as classroom visits, one-on-one mentoring, and meaningful feedback, to the more junior teachers who need help applying what they’ve learned in their classrooms. Over time, this would eliminate the need for outside groups to conduct generic, one-size-fits-all trainings and free up Title II funds for other needs, including the expansion and improvement of career ladder models.

Critiques & Responses

Teachers are already paid enough.

The average starting teacher salary in the United States is $36,141, and the average salary for teachers overall is $56,383.28 Some would argue that not only are teachers paid enough, but they are paid more than private-sector workers with similar skill sets, when taking other benefits into account.29 We disagree and think that these conclusions rest on weak, disjointed data points and a fundamental misunderstanding of the challenges that educators encounter as a part of their jobs. Yet even those who do not support raises for all teachers can see that the economy is changing, workers no longer stay in a single job for decades, and new generations of employees want to be rewarded for their performance on the job not simply for the number of years they have spent in it. Modernizing the teaching profession to make it align with those new expectations would help address our teacher retention crisis and fill the 3 million new teaching jobs we will have open over the next decade.

Private funding structures do not belong in public education.

Total K-12 public school spending amounts to nearly $700 billion every year, with per pupil costs increasing an average of 2.3% per year.30 With costs continuing to soar, we cannot afford to rely solely on taxpayer dollars. To be sure, several private corporations already invest in innovative programs through their philanthropies. In fact, J.B. Pritzker partnered with Goldman Sachs in 2013 to fund the very first social impact bond for an early childhood education program—an endeavor that provided United Way of Salt Lake City with $7 million.31 These types of investments do not give the private sector control over the operations of any publicly-run system. Instead, they provide an opportunity for businesses to invest in the future workforce without costing the public a single penny if the investment fails to yield cost savings.32

Overhauling teacher compensation structures is just another way to attack public employee unions.

The teachers that we need to fill our classrooms over the next decade will in large part come from the Millennial generation. These young people value opportunities to advance within their careers, and they want to be rewarded for a job well done.33 Expanding career ladder structures would achieve these two goals, and for that reason it is a policy idea that folks across the political spectrum should be able to get behind. Implementing career ladders for teachers would not necessitate an end to tenure nor would it eliminate the need for collective bargaining agreements—in fact many of the current models have been negotiated with local teachers’ unions. The bottom line is this: we must rethink the way we pay and promote teachers, and if we do so with the input of teachers, we will end up with a system that works better for everyone.

Appendix

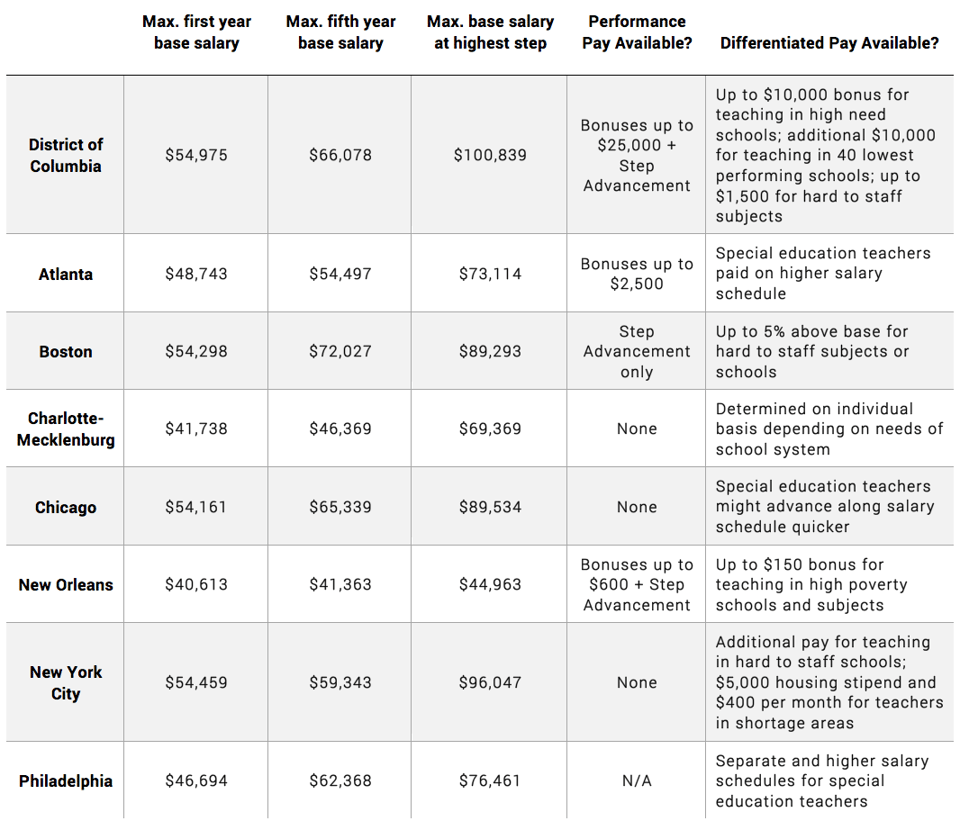

Maximum Base Salary in DCPS versus other major districts (based on data from the National Council on Teacher Quality)34