Memo Published March 22, 2012 · Updated March 22, 2012 · 6 minute read

Leaners Don’t Fall: The Myth of the Myth of the Independent Voter

Michelle Diggles, Ph.D. & Lanae Erickson

“Research by political scientists on the American electorate has consistently found that the large majority of self-identified independents are “closet partisans” who think and vote much like other partisans.”

-Alan Abramowitz1

Public opinion surveys confirm that approximately 40% of Americans consider themselves political Independents. Yet beltway wisdom often asserts that Independents don’t actually exist, positing that Independents really just lean towards one party or another and vote for that party’s candidate election after election. This view is often called the “Myth of the Independent Voter,” and, not coincidentally, it has frequently been adopted by strategists in both parties, who are quick to rely on it to persuade partisans that appealing to their own party members is sufficient to win elections.

New findings based on unique data reveal that Independents are distinct even from those who say they weakly identify with the Republican or Democratic parties. While analysts have often looked at Independents who lean one way or the other in a single election and concluded they are simply “closet” partisans, in reality those who label themselves Independent are much more likely to switch parties, and their votes, over time, from election to election. In this memo, we demonstrate that while some Independents may lean toward a certain party and vote for that party’s candidate in that same electoral cycle, when you follow the same people across multiple elections, a very different pattern emerges: these leaners don’t fall with their partisan friends.

In this memo we:

- Define partisans and Independents;

- Show that Independents who lean towards one party or another are more likely to defect from that party than partisans; and,

- Demonstrate that Independents are actual swing voters.

Most concerning for Democrats—Independents who lean towards the Democratic Party are even less reliable party voters than their Republican-leaning counterparts.

1) Partisans, Independents, and Independent Leaners

How do we define an “Independent voter”? Public opinion surveys, such as exit polls and Gallup surveys, often ask people to self-identify: “Are you a Democrat, Republican, or Independent?” Other surveys, such as the American National Election Studies (ANES),* asks two questions to come up with an answer. After first asking people to place themselves in one of the partisan categories, they then ask Democrats and Republicans if they are weak or strong partisans. This creates 4 categories of partisans—Strong Democrats, Weak Democrats, Strong Republicans, and Weak Republicans.

The American National Election Studies (ANES) conducts national surveys of the American electorate annually for use in academic study.

Independents, however, get a different follow-up question. Independents are asked if they lean towards one party or another. This results in 3 categories of Independents—pure Independents, Democratic-leaning Independents, and Republican-leaning Independents. We call the last 2 groups leaners—Independents who lean towards one party or the other—and distinguish them as Democratic Leaners and Republican Leaners.

The way we count and categorize voters has real implications. In 2008, ANES found that 34% of the electorate identified as Democratic, 26% as Republican, and 40% as Independent. But if we assume, as many do, that the leaners—Independents who say they lean towards either of the parties—are equivalent to partisans, the electorate looks very different. Democrats suddenly become 51% of the electorate, Republicans 38%, and Independents are 11%. Of course, if that were the case, Democrats would never lose!

Analysts lump leaners in with their respective partisans for good reason. As pollster Mark Mellman noted last fall, “In 2008, 90 percent of Democratic Leaners voted for Barack Obama and 82 percent of GOP Leaners supported John McCain.”2 But this conclusion rests on 2 assumptions about Independent Leaners over time:

- They are stable party-leaners; and,

- They are stable party voters.

2) Leaners’ Party Preferences Shift Over Time

Recently, St. Mary’s Professor Todd Eberly released an analysis with Third Way of a unique ANES panel study.3 ANES researchers followed the same people over 3 successive elections—2000, 2002, and 2004. The results revealed that Independent Leaners were significantly more likely to switch their party identification than were those who described themselves as Democrats or Republicans, or even weak Democrats and Republicans. And Democrats of all stripes—strong partisans, weak partisans, and leaners—were more likely to have left the party in subsequent elections than were Republicans.

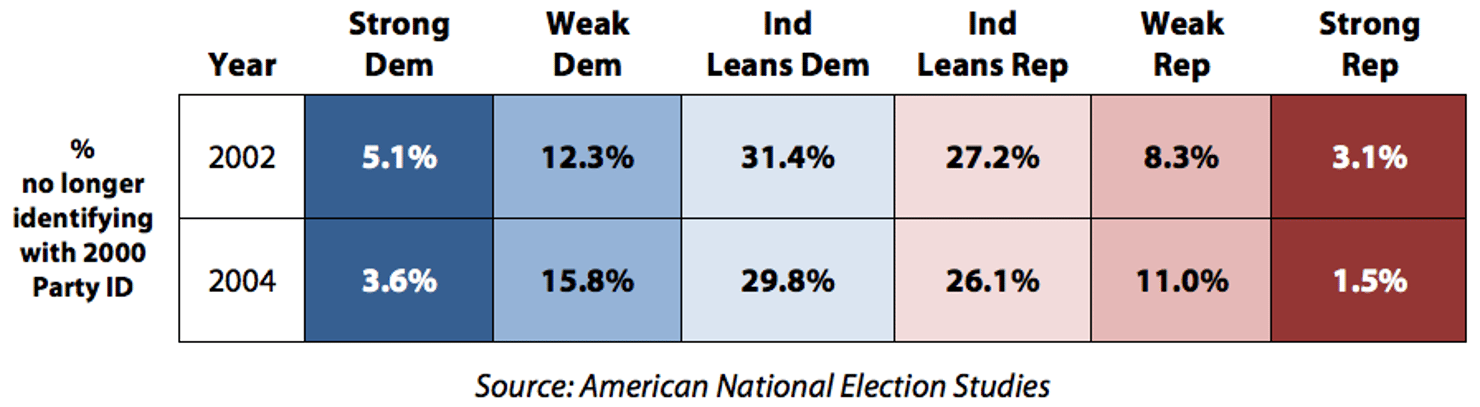

Table 1: Party Switching by Strength of Partisanship Following Voters from 2000 Party Identification through the 2004 Election

Leaners comprised one-third of the Democratic coalition in 2008 and 31.5% of Republican voters. Since Democratic Leaners were more prone to party defection in these elections than their Republican counterparts, the Democratic Party had less stable membership.

3) Leaners Swing-Vote Between Parties Over Time

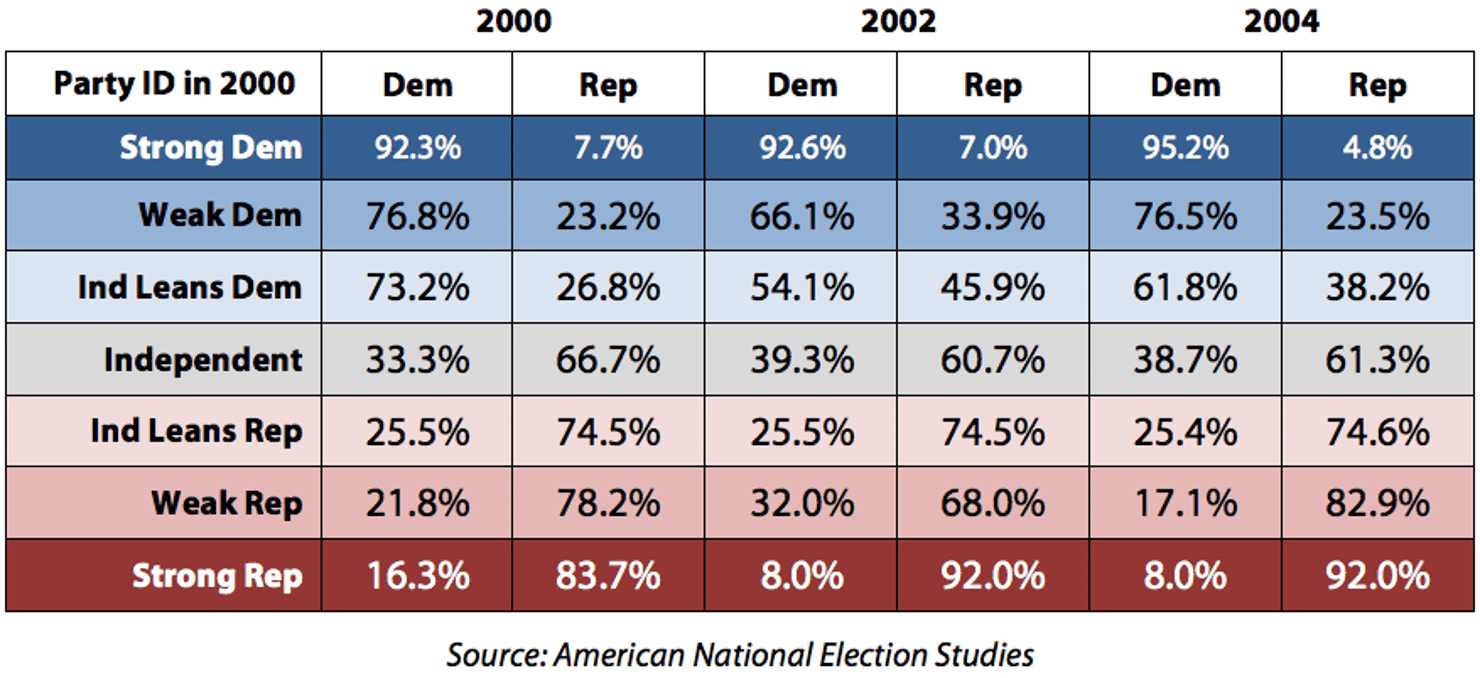

In 2000, 73% of Democratic-leaning Independents voted for a Democrat and only 27% for a Republican. This seems to confirm conventional wisdom—Independents largely vote for the party they lean towards. But by 2002, only 54% of Democratic Leaners were voting for the party and 46% had defected; by 2004, 38% of Democratic Leaners were GOP voters.4 When we follow the same voters across successive elections, the data clearly revealed that leaners are not party loyalists.

Table 2: Relation of Strength of Party ID to Partisan Regularity in Voting for the House of Representatives (2000, 2002, and 2004)—Based on 2000 Party ID*

Partisan vote choice was determined by calculating only the two party vote shares for each election. Respondents who indicated that they had not voted or did not indicate for whom they voted were excluded.

Compared to other Democratic-coalition voters, leaners were less reliable Democratic voters. Strong partisans voted for the party’s candidate over 90% of the time, and even weak partisans voted for Democratic candidates at super-majority levels. But the leaners were more prone to defect.

The trend with Democratic Leaners is especially problematic when comparing them with their counterparts across the aisle. In both 2002 and 2004, only one-quarter of Republican Leaners defected, while 75% remained loyal to the party. This means that Republican Leaners were more likely to pull the lever for their party’s candidate than Democratic Leaners over successive elections—although these were elections where the GOP was favored and future data may show this was an isolated phenomenon.

Conclusion

Independent voters are not a myth—they do exist, and even when they say they lean a certain way at one point in time, that allegiance is much less consistent than that of even weak partisans. But detecting those differences often requires data collected across multiple elections. In the 2000–2004 panel surveys—the only timeframe of this kind of data available—Democratic Leaners were swing voters and not reliable members of the big-tent Democratic Party—in sharp contrast to Republican Leaners, who voted for the GOP nominee nearly 75% of the time. If Democrats want to assemble a sustained majority, they will need to woo the leaners. But if they follow the party activists to the left, the tent will likely come crashing down.