Memo Published February 25, 2015 · Updated February 25, 2015 · 6 minute read

States Gone Wild: What Happens Without Federal Guardrails on Education

Tamara Hiler & Lanae Erickson

Congress is currently knee-deep in its attempt to reauthorize the Elementary and Secondary Education Act—better known as No Child Left Behind (NCLB). While there is wide bipartisan agreement that some provisions of the law need to be updated in order to better serve the needs of students and relieve states from the uncertainty of the Administration’s current waiver system, Republicans have chosen to go all in on a proposal that would essentially eliminate the federal government’s role in holding states accountable for how they are educating our nation’s students.

Specifically, the proposed drafts from Chairman Kline (R-MN) and Chairman Alexander (R-TN) would essentially allow states to set their own goals, design their own accountability systems, and come up with their own interventions for improving performance when the goals are not met. The federal government would have no real ability to intervene, even in schools that fail to meet performance goals year after year.

So what happens when we leave states completely to their own devices on education? Unfortunately, the evidence of state-based accountability eras-past doesn’t paint a promising picture. When looking at three different time periods spanning from pre-NCLB, to the NCLB era, to the current waiver system, it is clear that without any federal oversight, states have too often opted to lower their standards, obscure crucial data, and sideline the needs of their most vulnerable students.

State Actions Before NCLB

Prior to the 2001 passage of NCLB and the accountability that went with it, states were already required to set targets for “continuous and substantial improvement” that moved all kids, especially low income and English Language Learner (ELL) students, towards proficiency. However, without sufficient federal oversight or measurement for those targets:

- In 48 states, the performance of specific groups of kids like low income students, students of color, or English Language Learners was not a factor in the accountability system.

- 17 states simply didn’t put into place a statewide accountability system at all.

- States were able to get away with nonsensical accountability goals such as in Mississippi, where their stated goal was to “decrease the percentage of students scoring in the lowest quarter on state assessments”—a mathematically impossible feat.1

State Actions Under NCLB

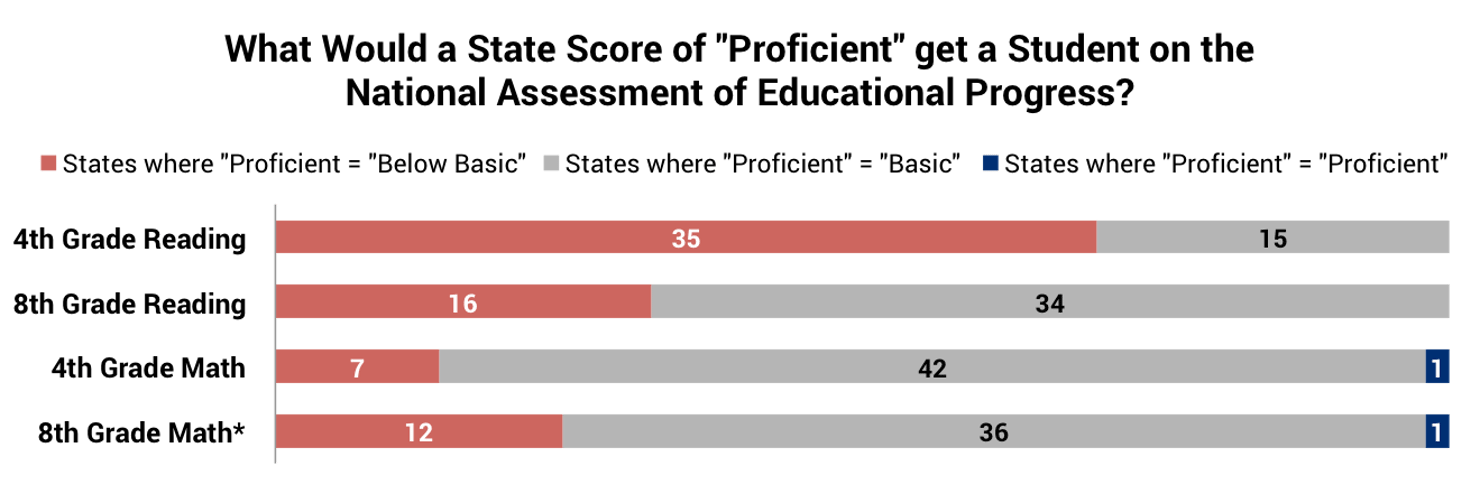

Even after NCLB was enacted, the flexibility built into the law allowed states to set their own bars for proficiency on state assessments. When given even this small allowance of flexibility, states attempted to inflate their students’ progress by both making their state assessments easier and by lowering the bar for proficiency on those tests. In fact, between 2005 and 2009, when states reported changes to their assessment systems, more than half of the reported changes were to make their standards less rigorous, while less than one-third of those changes actually increased the rigor of the standards. In addition, states consistently set the marker for proficiency at a level that was significantly lower than the proficiency marker of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a longstanding measure of academic progress for decades.2 In fact, 35 states awarded “proficient” marks for 4th grade reading performance at a level that would be considered “below basic” on the NAEP.

*8th grade math data is only available for 49 states.

But the flexibility around the definition of proficiency was not the only area in which states chose to use their discretion to lower expectations for students. As part of NCLB, states were required to use graduation rates to hold high schools accountable; however, the law also allowed states to set their own goals for what those graduation rates should be, as well as to create their own targets for moving towards those goals. Given this flexibility, the Education Trust found that:3

- Nearly 50% of states set their goals for graduation under 80% (the current national average), and six states set theirs below 60%; and,

- 28 states called it sufficient if they made any progress (including less than a point) towards their goals, and 2 states plus DC called it sufficient if they simply “didn’t get worse.”4

State Actions Under Post-NCLB Waivers

When Congress failed to rewrite the expiring NCLB in 2011, the Obama Administration began to administer waivers to states to relieve them of some of NCLB’s toughest provisions, including the demand that they demonstrate 100% proficiency in math and reading. Under the waivers, states were given the option to change their accountability systems in exchange for other Administration priorities. This loosening of prescriptions on accountability provided states with an out which some used to turn a blind eye to the performance of their most vulnerable students. A review by the Alliance for Excellent Education found that during this time period:5

- 9 states created systems in which low graduation rates for specific high-needs subgroups (i.e. students of color, students with disabilities, or ELL students) would not count toward identifying a school as one of the “focus” or “priority” schools in need of improvement.

- In 5 states, low graduation rates among those specific groups were not considered in the state’s accountability index—meaning a school could get top marks in the state even if its graduation rates for students of color or students with disabilities were abysmal.6

Conclusion

Given this storied history, it would be a mistake for Congress to once again blindly trust the states to hold their schools accountable, handing out $25 billion dollars in federal taxpayer money with no strings attached. When left to their own devices, some states have demonstrated time and time again that they are more than willing to relax their accountability standards, often at the expense of students who have been historically underserved, and often in an effort to produce a mirage of steady educational progress. Instead, the federal government has an important and necessary role to play in ensuring that states maintain rigorous accountability systems that protect and include all students, and that force action if schools are failing certain students or groups. Rather than completely abandoning the federal role in education, a new reauthorization of NCLB should permit states some flexibility to set their own goals and design interventions for failing schools. But it should also continue to provide reasonable federal guardrails and consequences if a state fails to meet its goals over and over again.