Memo Published June 25, 2014 · Updated June 25, 2014 · 15 minute read

Three Ways of Looking At Income Inequality

Alicia Mazzara & Jim Kessler

The President has turned a much needed eye to income inequality and the growing share of income accumulated by the top 1%. The government plays a key role in ensuring that the American economy works for everyone, and Democrats are rightly focused on building a post-recession agenda that addresses problems like low upward mobility among the poor and the fact that a middle class job no longer supports a middle class life. In order to respond most effectively to rising income inequality in America, it is useful for policymakers to understand how economists define the first part of that term: income. In this primer, we look at three commonly used—but very different—measures of income and show how each one impacts the share of total income captured by the top 1%.* All three measures show that inequality is on the rise, but how one defines income significantly affects both the level of income inequality and, most importantly, the actions policymakers can and should take to reduce it.

We refer to these as measures as “market income”, “market income and benefits”, and “after tax income.” Other authors may use different terminology to describe these concepts.

Measure #1: Market Income

Market income = money earned through work and investments before taxes

What is considered income? Income before taxes and government transfers is often referred to as “market income.” This measure is derived from gross income, a term used by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to record all sources of income on an individual’s tax return before deductions.1 Think of it as what each person earns from their jobs, businesses, private pensions, and investments.

What is not considered income? Income from government sources, such as Social Security and unemployment insurance, would not be counted under this definition. Additionally, this measurement does not include employer-provided health care or retirement benefits.

Under this definition, a person earning $50,000 a year with employer-provided healthcare and a defined-benefit pension plan would have the same income as a person earning $50,000 a year with no health or retirement benefits. Likewise, a retired couple receiving $30,000 a year in Social Security payments would not have that money counted toward their market income.

Market income includes—but is not limited to—income from an individual or married couple’s:

- wages and salary, including bonuses;

- realized capital gains;

- income from operating a business;

- pensions and annuities; and

- interest and dividends.2

Where does the data come from? The IRS publishes a large dataset of anonymized income tax returns. Economists have been mining this rich trove of data for years, but Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez are perhaps most famous for using tax returns to study income inequality in the U.S. and abroad. Piketty and Saez use a market definition of income.3 Along with other researchers, they have compiled the World Top Incomes Database which contains information on how much income the top 1% of earners makes. The statistics derived from this database are probably the most oft-cited by policymakers and the media.

What are the strengths and weaknesses of this data? Unlike other data sources, the IRS has detailed income information on very high earners. Since much of the rise in income has been among the top 1%, the IRS data is crucial to understanding recent trends in income inequality. IRS data is also available dating back to 1913, allowing researchers to track long-term trends. Moreover, tax returns are usually more accurate than surveys that ask people to report their income from memory.4

However, the IRS data does not include information on people who make too little money to file taxes. As a result, economists must estimate incomes for low-income persons if they are to calculate certain measures of income inequality. Tax returns may also underestimate incomes as some people engage in tax evasion or underreporting. Additionally, the IRS data does not include any capital gains income that is exempt from taxation, such as the sale of most homes.

How does this measure affect income inequality? Under this measurement, the top 1% of all earners captured 20% of all U.S. income in 2010 (the most recent year available for all three measures).5

Measure #2: Market Income and Benefits

Market income and benefits = market income + employer-provided benefits + government transfers

What is considered income? The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) uses this metric of income. It builds on Measure #1 (market income) by adding two more sources of income to the equation: government transfers and certain employer-provided benefits. This includes things like health insurance, 401K contributions, Social Security, and means-tested benefits like food stamps and public housing assistance. In other words, this measurement includes adjustments made by public policy regarding safety net benefits, as well as employer actions on non-wage benefits. Readers familiar with the differences between the official and supplemental poverty measure will likely recognize similarities to these income concepts.

This measure of income differs in one other important way from Piketty and Saez’s measure of market income. The CBO measures market income and benefits using households instead of tax filing units.* Households may consist of multiple tax filers and consequently tend to have higher incomes than tax filing units.6 Even so, a family of three making $90,000 arguably has less spending power as a single adult earning the equivalent salary. To better reflect the true spending power of households over time, the CBO adjusts market income and benefits by household size.*

A tax filing unit may consist of a married couple or a single individual, with or without dependents.

In order to adjust for household size, the CBO divides total income by the square root of the number of people in a household.

Market income and benefits includes—but is not limited to—

income from a household’s:

- wages and salary, including bonuses;

- realized capital gains;

- income from operating a business;

- pensions and annuities;

- interest and dividends.

- 401K contributions;

- employer-paid health insurance premiums;

- employer’s share of payroll taxes; and

- estimated value of government cash transfers and in-kind benefits.7

What is not considered income? Most items that pertain to the tax code are not included. For example, benefits from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) would not show up as income under this measurement. Taxes paid are also not deducted from income.

Where does the data come from? The CBO relies on two sources to calculate market income and benefits: IRS income tax returns and the Current Population Survey, a monthly survey of 60,000 households administered by U.S. Census Bureau. The IRS tax returns are the same as those used to calculate market income. The survey data provides information on employer and government-provided benefits.

What are the strengths and weaknesses of this data? This measurement contains information on non-wage benefits, an important barometer of well-being not captured by market income alone. Additionally, the survey data contains information on persons who make too little money to file for federal taxes, unlike the IRS data. By combining both data sources, this measure provides a more complete picture of income in America. However, both data sources may underestimate incomes, either due to tax evasion or underreporting on the tax returns or from human error in the survey.

How does this measure affect income inequality? Under this measure, the top 1% of earners captured 15% of all U.S. income in 2010 (the most recent year available).8 The top 1% captured three times the income share of the bottom 20% and almost the same share of income as the entire middle 20% of earners (see Table 1).9

Measure #3: After Tax Income

After tax income = market income + employer-provided benefits + government transfers – federal taxes.

What is considered income? After tax income subtracts federal taxes from Measure #2 (market income and benefits). After tax income can be considered a measurement of “purchasing power” and answers the question: What does a household have once all wages, benefits, and government assistance are combined and federal taxes are removed? The CBO subtracts federal personal income, corporate, payroll, and excise taxes for their calculation of after tax income. Tax credits, including refundable credits like the EITC, are also included in this measure.

After tax income includes—but is not limited to—income from a household’s:

- wages and salary, including bonuses;

- realized capital gains;

- income from operating a business;

- pensions and annuities;

- 401K contributions;

- employer’s share of payroll taxes;

- employer-paid health insurance premiums;

- estimated value of government cash transfers and in-kind benefits; and

- federal tax refund and credits,

- minus the household’s federal tax liability.

What is not included in income? State and local taxes are the main item missing from this calculation. In high tax states like California, state and local taxes can surpass 10% of income for those at the top.10 Certain federal taxes—like the estate and gift tax—are also excluded from the CBO’s calculation of after-tax income. In addition, this measure does not include any capital gains income that is exempt from taxation, such as the sale of most homes.*

Although this is the most comprehensive income measure discussed in this paper, some economists use an even more inclusive definition of income. This measure would include things like the estimated income a homeowner would receive if they rented out their property; the value of in-kind employer benefits like a gym membership or company car; or any unrealized capital gains on investments.

Where does the data come from? The CBO uses this metric of after tax income. They rely on the same sources used to calculate market income and benefits—IRS income tax returns and the Current Population Survey.

What are the strengths and weaknesses of this data? Because it relies on the same data sources, the after tax income measure is subject to many of the same strengths and weaknesses as Measure #2 (market income and benefits).

In an ideal world, there would be data available to estimate all federal, state, and local taxes. In reality, many taxes are very difficult to estimate at this scale—especially state and local taxes. However, it is reasonable to expect that state and local taxes affect income inequality in ways that are not captured in the data. For example, 24 states plus the District of Columbia have their own Earned Income Tax Credit for the working poor.11 This is not included in these calculations. Additionally, the CBO does not include the federal estate tax in their calculations. This tax only affects very high earners, but some readers may want to know how estate taxes impact those in the top 1%.

How does this measure affect income inequality? Under this measure, the top 1% of earners captured 13% of all income in 2010. Using after tax income, the top 1% captured over twice the income share of the bottom 20% of earners and slightly less than the share captured by the middle 20% of earners (see Table 1).12

As shown in Table 1, the share of after tax income going to the top 1% in 2010 was a third smaller than the share measured using market income (20% vs 13%). Table 1 also illustrates the progressive effects of the tax code, with the middle and bottom 20% capturing a slightly larger share of all U.S. income after taxes.

Table 1. Income Inequality by Income Measure (2010)13

Share of all Income going to the… |

Top 1% |

Middle 20% |

Bottom 20% |

#1 Market Income |

20% |

N/A |

N/A |

#2 Market Income and Benefits |

15% |

14% |

5% |

#3 After Tax Income |

13% |

15% |

6% |

Note: Estimates of market income are not available for the middle and bottom 20%.

Source: Alvaredo et al 2013; Congressional Budget Office 2013.

How Do Different Measures of Income Affect Income Inequality?

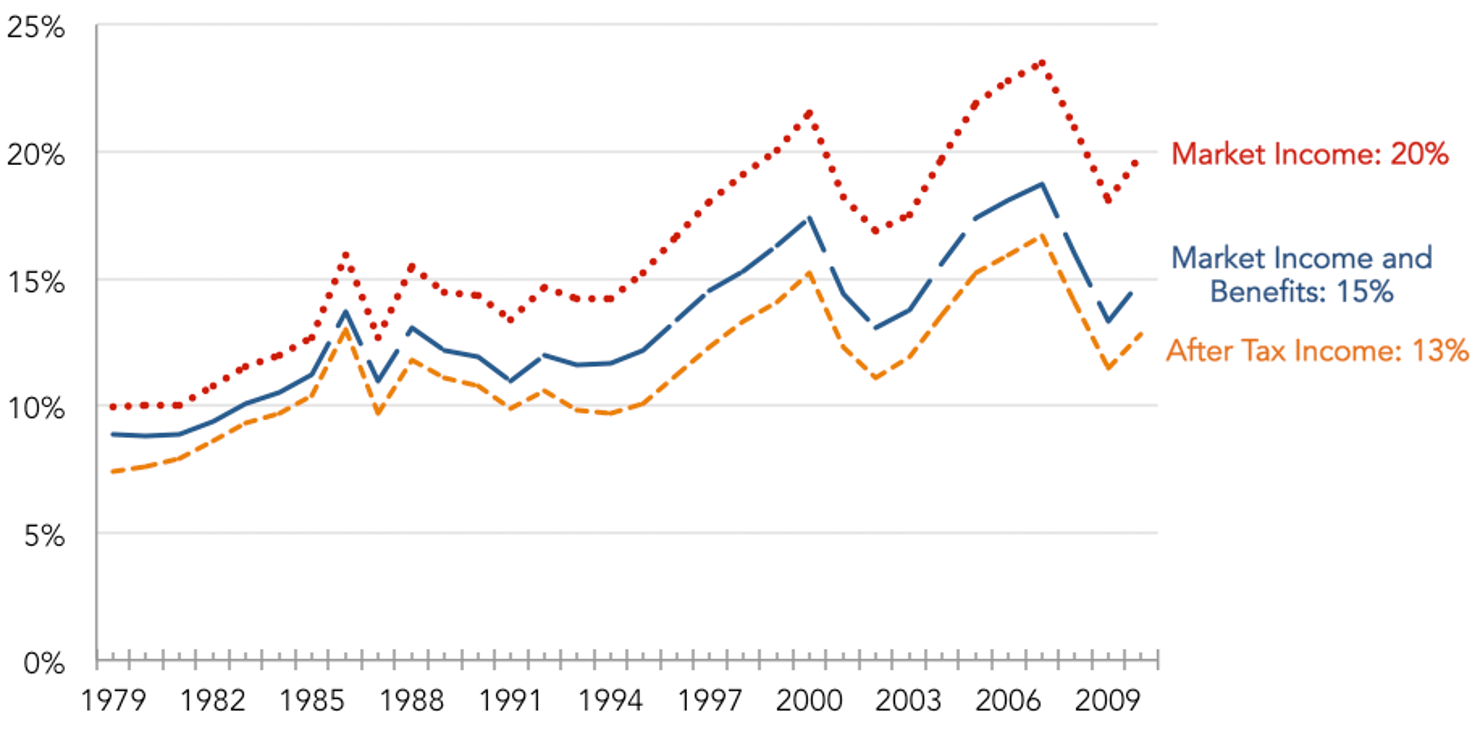

Figure 1. Share of Income Captured by the Top 1% (1979-2010)14

Source: Alvaredo et al 2013; Congressional Budget Office 2013.

Figure 1 shows the share of income captured by the top 1% of earners from 1979 to 2010, the most recent year available. The graph shows that there has been a clear rise in income inequality since 1980. The share of income accruing to the top 1% has nearly doubled since 1979, regardless of which income measure is used.

Although the data sources are not quite comparable,* the graph also indicates that government programs and the tax code have played a role in mitigating some, but not all, of the rising income inequality over the last 30 years. To understand why inequality was not reduced further, we must examine changes in federal taxes and government transfers during this period. Between 1979 and 2010, the growth of universal programs like Social Security and Medicare meant that low-income Americans received a proportionally smaller share of government transfers in 2010 because middle and upper income retirees receive these benefits as well.15 Meanwhile, the average rate for the individual income tax—the most progressive component of our tax system—fell between 1979 and 2010 (though it has risen since 2010 based on new taxes in the Affordable Care Act and the 2012 fiscal cliff deal).16

This is because market income is measured using individual tax returns while the other lines are measured using household tax and survey data.

Policy Implications

Each of these measures has very different public policy implications. If policymakers want to reduce income inequality based on a measure of market income (Measure #1), they might pursue proposals like raising the minimum wage or placing limits on the incomes of top earners. This is because market income only captures a person’s earnings from working and investments and does not include government and employer-provided benefits or taxes.

If policymakers are concerned with income inequality based on a measure of market income and benefits (Measure #2), they may wish to focus on interventions that increase non-wage benefits. Some examples include strengthening safety net programs like TANF, SNAP, or housing assistance; increasing Pell grants; expanding Medicaid eligibility; or creating employer mandates for health insurance and retirement.

And if policymakers are concerned with income inequality based on a measure of after tax income (Measure #3), in addition to the policies listed above, they may propose raising taxes for the wealthy; boosting the Earned Income Tax Credit for the working poor; or increasing subsidies for people purchasing insurance through the healthcare exchanges.

Table 2. Income Measures Affect Policy Choices

Will This Policy Lower Income Inequality? |

Market Income |

Market Income + Benefits |

After Tax Income |

Raise the minimum wage |

X |

X |

X |

Place limits on the incomes of top earners |

X |

X |

X |

Strengthen safety net programs |

|

X |

X |

Create employer mandates for health insurance and retirement |

|

X |

X |

Increase Pell Grants |

|

X |

X |

Expand Medicaid eligibility |

|

X |

X |

Raise taxes on the wealthy |

|

|

X |

Increase the Earned Income Tax Credit |

|

|

X |

Increase Affordable Care Act insurance subsidies |

|

|

X |

While beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to note that income is just one facet of inequality that policymakers should consider. None of the measures discussed in this paper consider the value of an individual’s or household’s wealth. Wealth is another important indicator of economic well-being, and the level of wealth disparity and wealth concentration in the U.S. is also shaped by an array of government policies.*

Demographics are another factor that may influence how policymakers understand and respond to income inequality. For instance, households have become smaller over time, meaning that incomes are also supporting smaller families. Additionally, an increase the number of retired Baby Boomers means a growing number of households that no long earn income from work.

Conclusion

Over the last 100 years, the U.S. has come to recognize the problems that can be created by unfettered capitalism. Our government plays an important role in the economy by correcting markets so they may function more efficiently and equitably. In the United States, we have tried to correct for capitalism’s failings principally through public policies that redistribute income after people have earned it, rather than limit what people can earn. This broad national consensus has given rise to historic government programs like the adoption of the income tax in 1913; Social Security in the 1930s; the Great Society anti-poverty efforts of the 1960s; and the passage of Affordable Care Act in 2010.

If one wants to understand the full effect of progressive taxation and other critical government programs of the last century, one must use the after tax income measure (Measure #3). Important policy interventions—such as increasing the Earned Income Tax Credit or expanding the number of housing vouchers—will affect income disparities under certain measures but won’t register on others. For example, the return to the Clinton-era tax rates and the new taxes on the wealthy from the Affordable Care Act would only affect income inequality under the after tax income measure; using either of the other two measures would mask the impact of these and similar crucial policy interventions.

Progressives have engaged in ongoing efforts to combat income inequality over the last 100 years. Many leading economists, journalists, and the White House have rightly expressed serious concern over a recent rise in income inequality. But if policymakers do not use the after tax and transfer income measure (Measure #3) as a tool to analyze inequality, they will be left with few options to meet this urgent national challenge. While each measure of income discussed in this memo is legitimate, for the purposes of public policy we view the after tax measure of income (Measure #3) as the most fertile. Progressives should be proud of their accomplishments—both in practice and, arguably, in their measurements.