Report Published October 5, 2015 · Updated October 5, 2015 · 11 minute read

Pound. Dollar. Renminbi? What China's Push to Globalize its Currency Means for the United States

Tanner Daniel & David Brown

Takeaways

- The dollar’s international predominance allows the U.S. to borrow cheaply and easily, boosting U.S. economic growth by 0.3% to 0.5% annually.

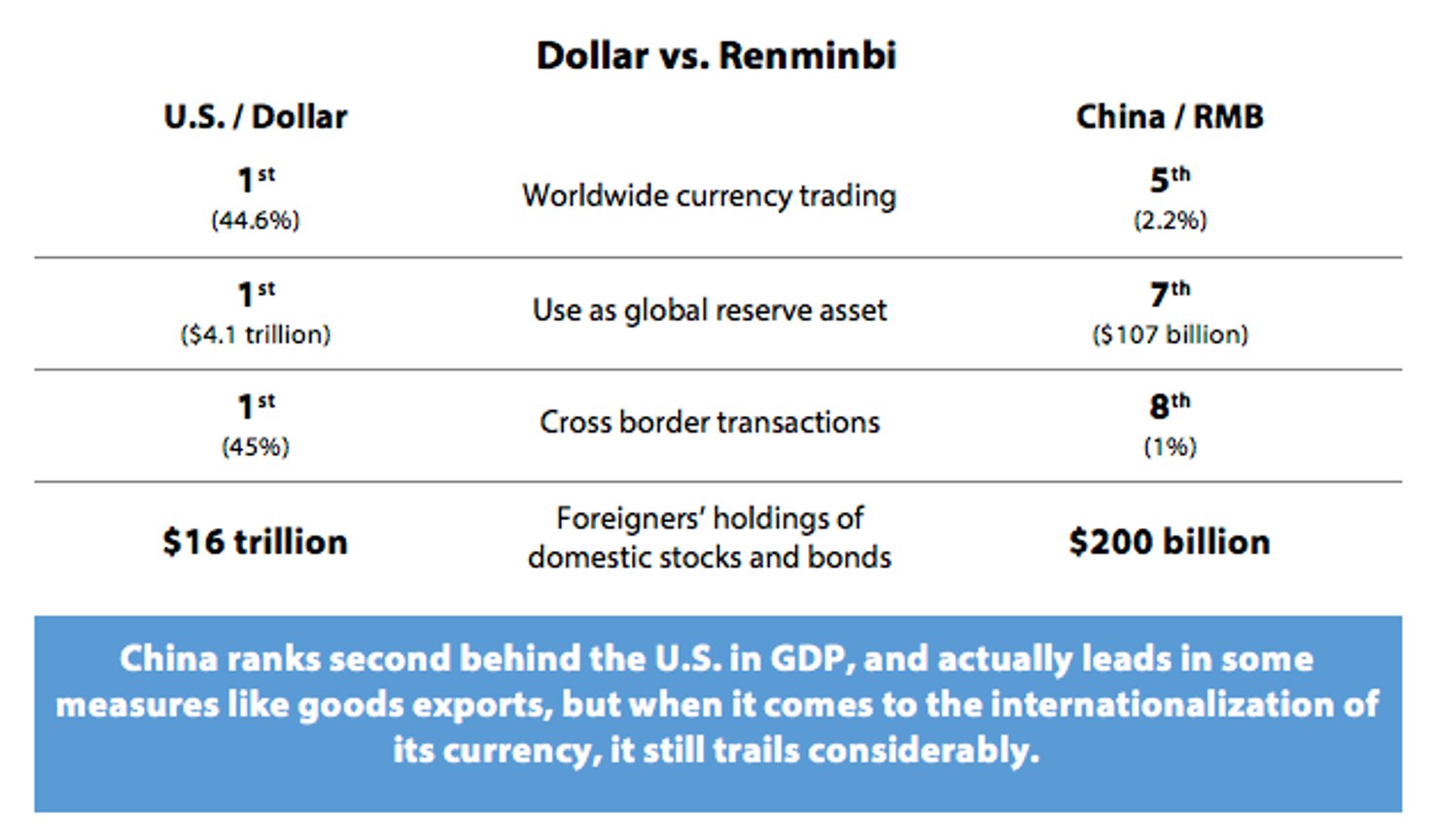

- China’s currency, the renminbi, is well behind the dollar internationally, but China wants to challenge the dollar’s top status in the coming decades.

- In November 2015, the renminbi won the IMF's approval to join the SDR, the elite basket of global reserve currencies (previously only including the dollar, euro, yen, and pound).

- During Chinese President Xi Jinping’s September visit to Washington, the U.S. announced it would support China’s inclusion, so long as the renminbi meets IMF criteria.

The dominant dollar

The United States has a gross debt-to-GDP level (105%) that would throw some European economies into a debt crisis, yet America easily attracts lenders willing to buy treasuries for practically zero interest.1 China and Russia are critical of American power, yet banks from both countries have backed U.S. sanctions against Iran. What do these American feats have in common? They could not happen without the global supremacy of the U.S. dollar.

When businesses conduct trade overseas, when foreigners invest outside their home countries, and when central banks stock up on currency reserves, they overwhelmingly use the dollar. That preference creates stronger demand for U.S. government bonds.

The result? U.S. risk-free rates are lower than they otherwise would be. Thus, Americans borrow more cheaply, finding it less expensive to start a business, take out a home loan, or charge a credit card. For the federal government, it’s cheaper to finance an $18.1 trillion national debt.2 And since the U.S. government—unlike most others—borrows in its own currency, shifting exchange rates don’t threaten to make its debt more expensive. These benefits together well outweigh the downside: a stronger dollar, which makes our exports less competitive. According to The McKinsey Global Institute, the dollar’s reserve-currency status adds between 0.3% and 0.5% to our growth annually.3 In the realm of foreign policy, the dollar’s reserve status gives U.S. economic sanctions a larger bite: because we can exclude foreign banks from making the dollar transactions so necessary in international trade, such sanctions pose a powerful economic threat.4

The best option, for now

The dollar’s dominance began after World War II, when the world’s developed nations met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire and agreed to peg the value of their currencies to the dollar. The hope was to create stable currencies that would increase international trade and decrease war. The U.S. was the logical choice. It had the strongest economy and two-thirds of the world’s known gold stockpile. The U.S. pledged that any nation could forever exchange dollars at $35 per ounce of gold.

“Forever” lasted 25 years. The Great Society programs of the 1960s coupled with Vietnam War spending led the U.S. to rapidly expand the money supply. Suspecting the gold reserves couldn’t continue backing those dollars, several countries exchanged dollars for gold, depleting the U.S. gold stockpile by more than half.5 In 1971, President Nixon announced that dollars could no longer be exchanged for gold, and the dollar began to float. The Bretton Woods System collapsed.6

The demise of Bretton Woods only strengthened the position of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Many countries already had dollars in reserve and had a vested interest in maintaining the dollar as a reserve currency. Plus, the dollar had traits desired in a reserve currency that no other currency could match. The dollar was liquid, meaning it could be bought and sold at will. It had deepness, meaning large amounts could be traded without affecting the price. And it was predictable, meaning the U.S. economy backing the dollar was strong and stable.7 Those advantages remain today. The dollar now accounts for 63% of all central bank reserves; the euro accounts for 22%, and the pound and yen most of the rest.

But having the world’s premier reserve currency is not a right. Once, the British pound was king. While no currency stands to knock off the dollar in the next decade, there is a big challenge on the horizon: China’s currency, the renminbi.8

The renminbi’s challenge

It’s too soon to tell if China wants the renminbi to topple the dollar, but it certainly wants to challenge it. Some Chinese economists think the renminbi can rival the dollar in 15 to 20 years.9 The potential benefits to China are clear. An internationalized renminbi would drive demand for it, lower China’s borrowing costs, and boost growth. A globally pervasive renminbi would reduce the threat of America’s sanctions, and possibly increase that of China’s. A pervasive renminbi would reduce the power of the Federal Reserve in setting global monetary conditions—something China isn’t crazy about nowadays, as a looming Fed rate hike threatens to further draw capital to the U.S. and away from struggling emerging markets, like itself.

The renminbi has made significant progress by some measures. It is advancing quickly as a currency used in international trade. In 2009, only 0.02% of China’s trade was paid for using the renminbi; in 2014, it was 25%.10 In transactions between China and other Asian countries, the renminbi has an even larger share. Also, China will soon open a new system for processing cross-border renminbi payments—enabled by 15 offshore clearing centers—in hopes of competing with the U.S. payments system.11

See 12 for source information.

By other measures, like cross-border transactions, the renminbi is far behind. China imposes strict limits, which it is gradually loosening, on financial flows in and out of the country. In another key area—the use of the renminbi by central banks as a reserve currency—China is behind though showing progress, having moved from virtually nothing to 7th in the world over the last 5 years.13

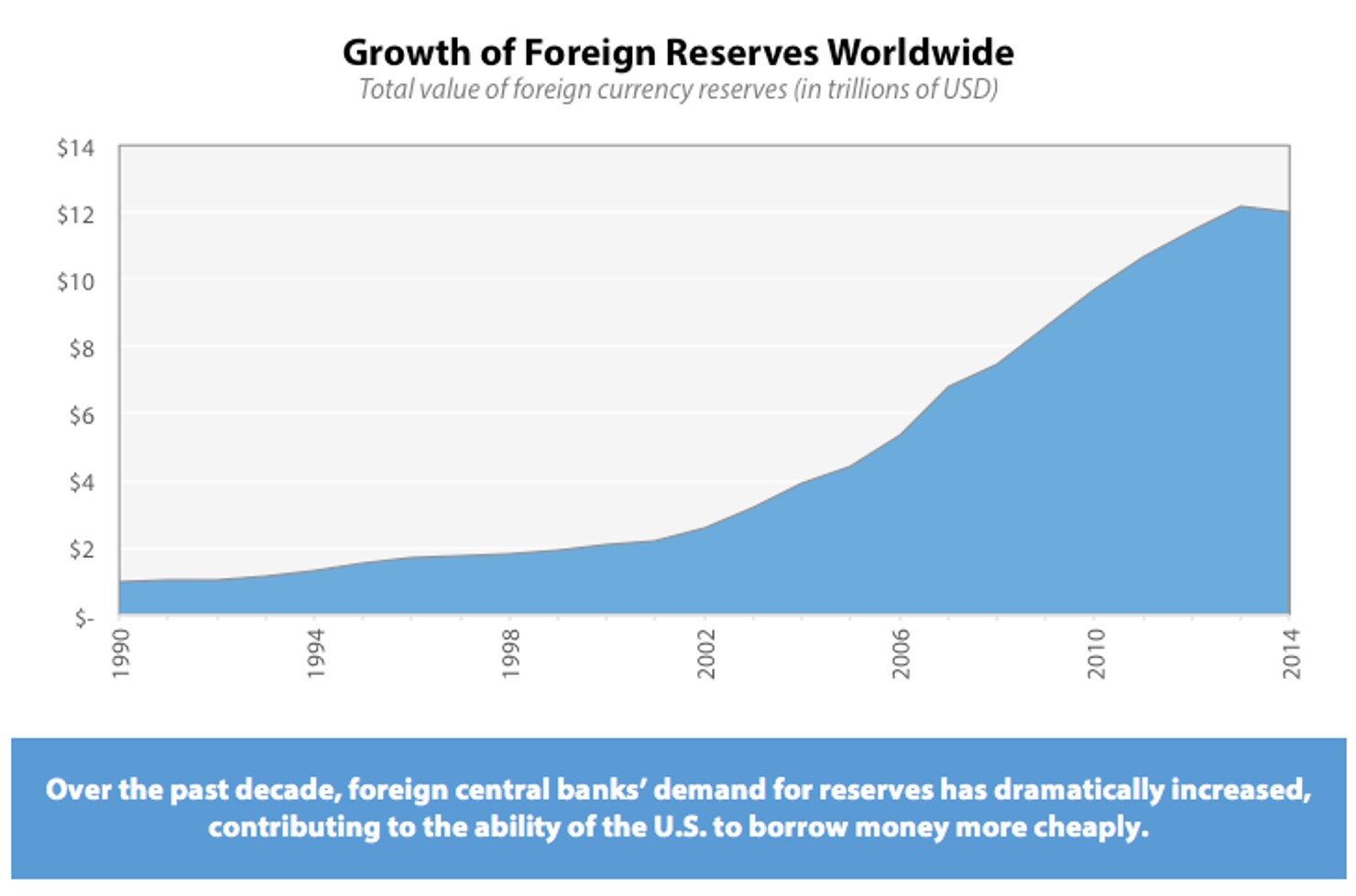

Having a true reserve currency would help China because it would create a huge demand for renminbi around the world. In recent decades, countries have acknowledged the importance of reserves and significantly ramped up their total holdings, from $1.4 trillion in 1995 to $10.2 trillion in 2011 (see chart).14 Countries accumulate foreign currency reserves for several reasons. First, reserves can be used in emergencies and help to manage exchange rates. If a country’s economy is hit with a shock and sees the value of its currency start to fall, it can use reserves to buy up its own currency on the market, reducing its supply and pushing up its value. Abundant reserves reduce the chance a country will need an emergency loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which in the past has come with painful preconditions.

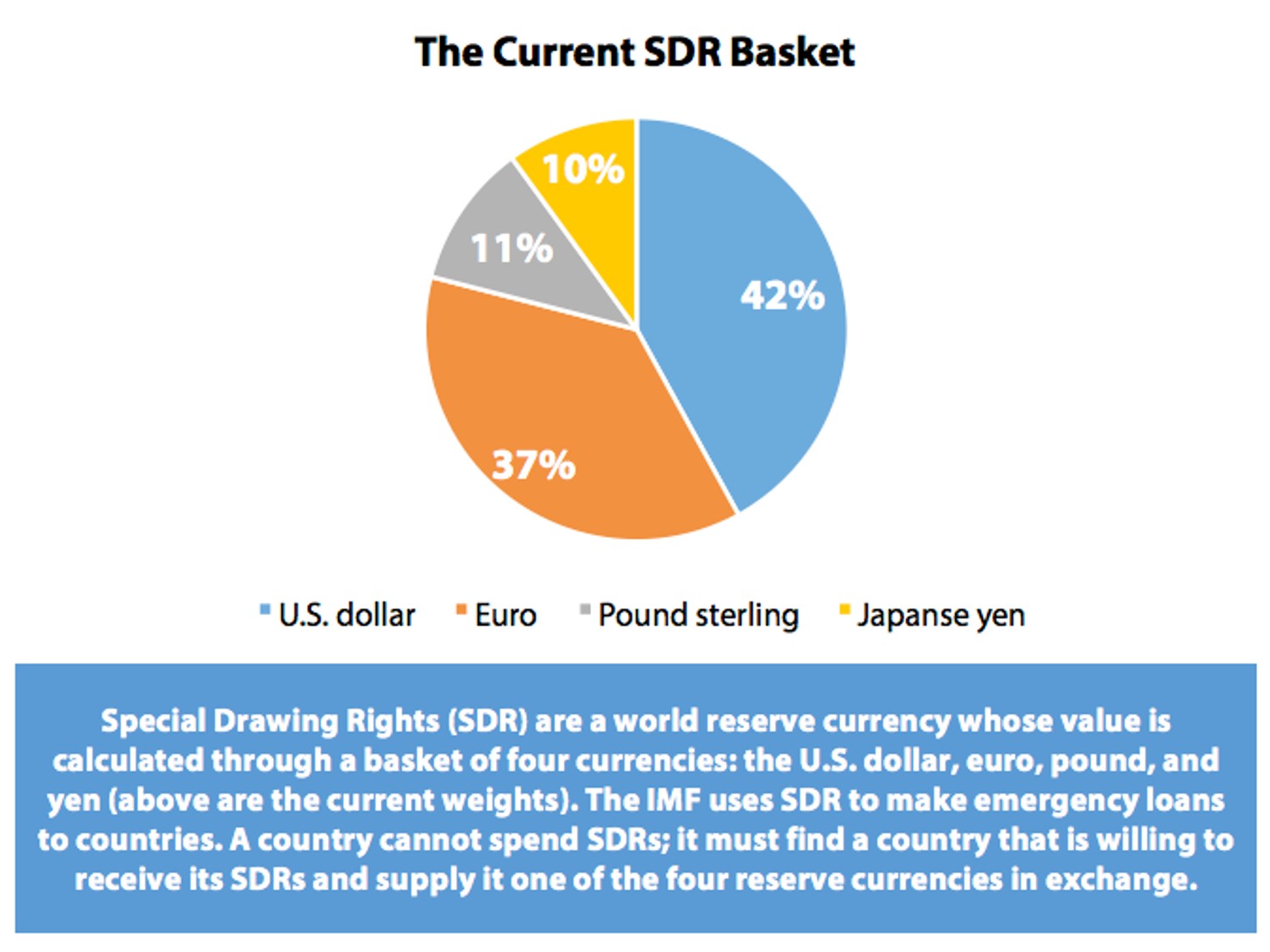

That’s where the current IMF review of China’s petition to become a “Special Drawing Rights” currency comes in. With the IMF approving China’s application at the end of November 2015, it has provided a seal of approval that the renminbi is competent as a reserve currency—along with the dollar, euro, yen, and pound.

See 15 for source information.

The SDR battleground

Special Drawing Rights (SDR) are a form of currency—sort of. There are no SDR coins or bills. Unlike as is the case with bitcoin, there’s no way to buy goods or services with SDRs… anywhere. That’s because the only entities allowed to hold SDRs are the central banks of IMF member countries. The IMF doles out SDRs to each country, based on its voting share with the IMF (which is based on the size of its economy). The central banks then hold SDRs as a reserve of last resort. If they run low on reserves, they can swap SDRs with another central bank for dollars, euros, pounds, or yen. Originally, one SDR was equal to one dollar, but today its value is set based on a weighted average of those four currencies, with the dollar carrying the largest weight, at 42%.

See 16 for source information.

During the financial crisis in 2009, a number of countries tapped their SDR reserves. For example, Bosnia and Herzegovina that year sold SDRs to finance its budget deficit. And Ukraine sold SDRs, because it needed cash to pay natural gas suppliers.17 Once a country dips below its allotted number of SDRs, it has to make interest payments on that deficit. Conversely, countries that build up a surplus of SDRs receive interest. Overall, SDRs make up a fairly small portion of central bank reserves worldwide, only 2%.18 They aren’t a part of day-to-day monetary policymaking. But SDRs do serve as a helpful backstop, providing liquidity to the global economy, especially in times of crisis. With the renminbi's admission to the SDR in November 2015 comes prestige for China as it continues to increase its role in international finance.

But it’s only a first step. Leading up to the decision, analysts predicted that the renminbi will make up only about 5% of the basket–a sliver of the total.19 Central banks around the world still have to choose to hold renminbi. And when facing that choice, they’ll still see a currency with problems for international use, most notably the restrictions on financial transactions moving in and out of China. And while the IMF now calls the renminbi fairly valued, it was only a few years ago when China was being widely accused of holding its currency artificially low to pump up its exports.

Also, China faces a near term risk of currency devaluation. In recent months, foreign investors have fled China, selling renminbi on the market. The People’s Bank of China (China’s central bank, PBOC for short) maintains the renminbi’s value in a 2% band in relation to the dollar, so it has had to use reserves to buy up extra renminbi to hold up its value. That’s why in August, it announced a 2% devaluation, to ease the downward pressure the market was putting on the renminbi. If foreign investors continue pulling money out of China and selling renminbi, the PBOC may have to let the renminbi drop even further—as other Asian currencies have already done.20

What’s at stake

For the U.S., China’s status as a reserve currency means little in the immediate term. After all, we already face competition from other reserve currencies and manage nicely. But, if the U.S. loses major reserve market share to the renminbi, it could weaken our influence, raise our borrowing costs, and hurt our economy. Over the next two decades, the status of a dominant dollar would be hugely valuable to hold onto, as the aging of the baby boomers pressures the federal budget with growing obligations for health care and retirement spending.

Now that the renminbi has joined the SDR, an important experiment has begun. Never has a country with such a state-run economy been included in the SDR. Yet during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s first official visit to the U.S., the Obama administration signaled it is outwardly positive about SDR inclusion.21 This, in part, may be because it realizes it can’t stop China—European allies have been more supportive of the renminbi’s inclusion. The U.S. may not want to risk losing after having embarrassingly failed to block China’s launch of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank earlier this year.22 IMF Managing Director and former French finance minister Christine Lagarde said in March, “It’s not a question of if, it’s a question of when.”23

On the other hand, allowing China in, some say, might lead to a renminbi with a more market-determined exchange rate—and a further opening of the Chinese financial system—something the White House and many in Congress have long demanded. Because China is expected to remain an engine of growth in years ahead, opening up its capital markets can benefit the global economy.

But as in other policy areas, China’s actions can’t be easily predicted. For the United States, that means the challenge is to carefully allow China’s integration into the international system, while also maintaining the traits that led to the dollar’s preeminence in the first place. Although it is unlikely to be reached in the near future, there is some debt-to-GDP level at which lenders would look at the U.S. economy and decide it’s safer to invest elsewhere. The sooner America gets its long-term debt on a sustainable course, the more likely it will be to retain that top-dollar status for decades to come.