Blog Published December 6, 2022 · 11 minute read

5 Things We Don’t Know About Graduate Student Debt

Chazz Robinson

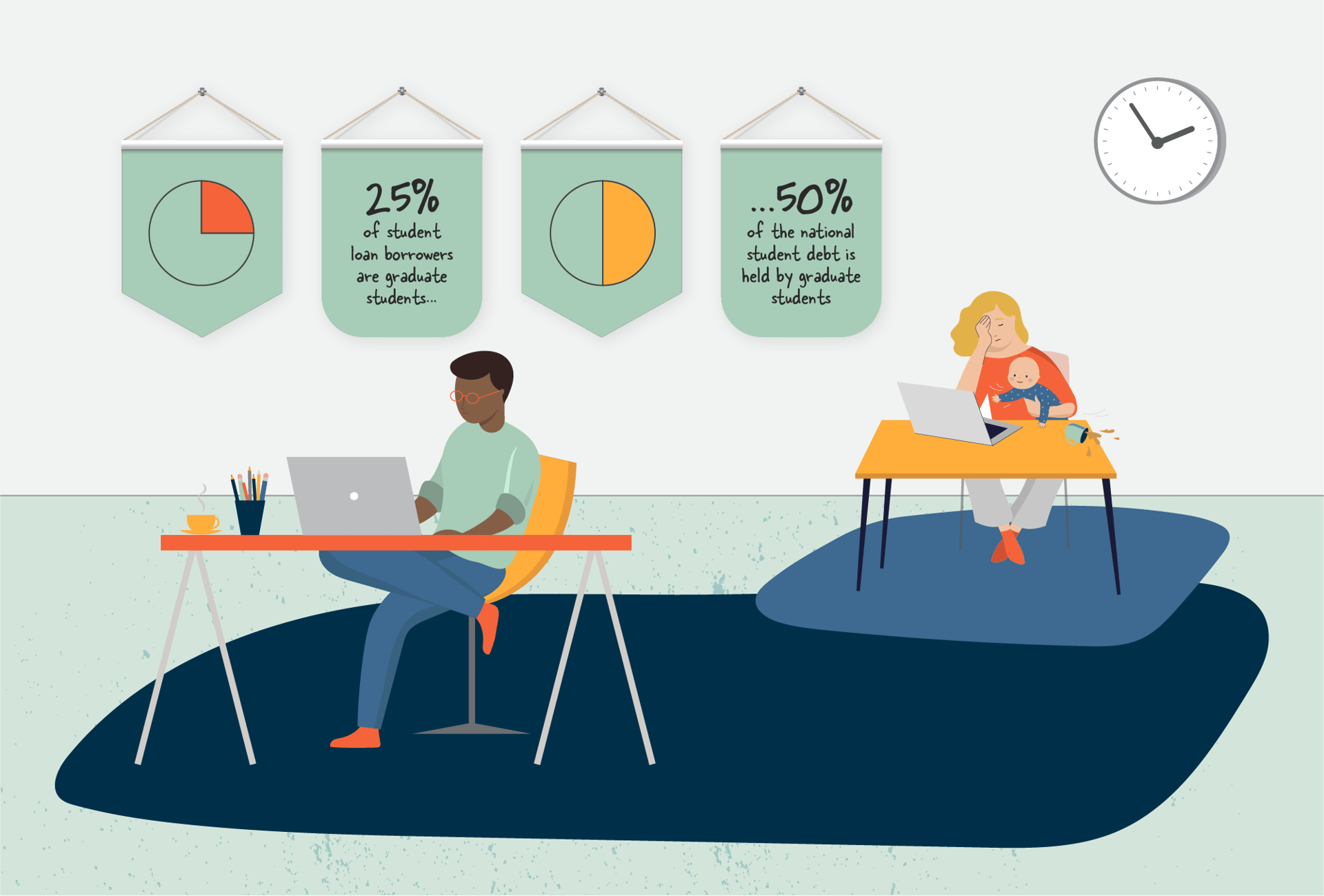

What if I told you there is a group of taxpayer-supported students larger than the populations of Chicago and Houston combined which we know minimal information about? Welcome to the conversation about the four million enrolled students attending graduate programs in the US. The Census Bureau reported that despite an overall decline in college enrollment, graduate school enrollment rose 8.1% between 2011 and 2018—and with enrollment steadily increasing, so has graduate student borrowing.1 Graduate students make up 25% of student loan borrowers, and hold 50% of the national student debt.2 Despite this outsized influence in the loan debate, graduate students have received a minuscule amount of policy attention compared to undergraduates, and graduate education continues to escape any federal accountability.

Graduate programs have primarily operated with little to no oversight by the federal government—despite being funded by federal loans. Institutions participating in federal student aid programs are required to complete over a dozen comprehensive surveys within the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), but the only publicly available data on graduate education focuses on enrollment figures—and no IPEDS surveys report graduation rates for graduate programs.3 The absence of available graduate program data on the federal level has led many to blindly assume that all graduate schools are equitably serving students and setting them on a track to success. However, questions about the outcomes of graduate students in specific programs and institutions have begun to percolate.

Whether graduate programs are genuinely improving students' outcomes is a question that deserves ample attention and policy response. This memo highlights five major unknowns around graduate students and debt for graduate school that are helping hide its complications from the national conversation.

1. Who completes graduate school?

Applications for graduate admission rose by 7.3% between 2019 and 2021.4 That increase indicates that there is high interest in various graduate programs—even in a time of declining undergraduate enrollment. However, despite that growth, information on who completes graduate education is not readily available on the national level and graduate programs are not required to report any information on non-completers to the public. This data is crucial because non-completers do not get the benefit of having the degree or credential they sought on their resume, and we see at the undergraduate level that non-completers are much less likely to be able to repay their loans and more likely to default. This dynamic likely extends to graduate borrowers and could potentially be even more pronounced given that they often hold larger cumulative debt loads. Yet where collected, detailed graduate program completion data are often kept within institutions, and publicly available data are often suppressed, ostensibly to protect student privacy. What little is known about the completion of graduate education at the federal level comes largely from the IPEDS completion survey and national longitudinal surveys conducted periodically—essentially polls of graduate students, not hard data.

Nationally representative sample surveys such as the National Postsecondary Student Aid Survey (NPSAS) and the Baccalaureate & Beyond (B&B) survey provide some useful information on graduate education. However, specific program-level data is not collected and institutions are not required to submit data on their student outcomes to these surveys, which makes it difficult to compare completion rates across institutions. Also, these available surveys focus on different issues within graduate education, which limits the applicability of the results on a national level. In comparison, undergraduate institutions’ program-level graduation rates are federally-collected and published annually. In fact, there are three IPEDS surveys that focus on undergraduate graduation rates.5 To make this data useful and accessible for researchers, policymakers, and potential students alike, federal undergraduate data collected through IPEDS contribute to widely used public data tools such as the College Scorecard.

It is important to note that undergraduate-level student outcomes data are not without shortcomings. The federal ban on a student unit record system makes current data insufficient for fully understanding how students fare in higher education, and there is a clear need for robust transparency improvements across the board, including overturning the ban through the passing of the College Transparency Act. However, prospective undergraduate students do at least have access to tools like the College Scorecard, which incorporates federal reporting from institutions, data on federal financial aid, and tax information to provide a baseline level of transparency around student outcomes. Graduate students do not have any comparable platform, leaving them in the dark about the outcomes they might expect from programs they are considering. Student borrowers and the wider public cannot determine what graduate programs have strong completion rates. Underinformed decisions increase the likelihood of students taking on a staggering amount of debt for a program that struggles with getting students across the finish line to degrees. Without consistent data reporting, students will continue to be left to operate on poor information, allowing underperforming graduate schools to continue to escape scrutiny.

2. How are taxpayer dollars used to fund graduate education?

There are two federal loan programs that graduate students use to fund their education: Direct Unsubsidized Loans and Graduate PLUS (Grad PLUS) Loans. Graduate students can receive $20,500 annually through a Direct Unsubsidized Loan, capped at $138,500 total.6 However, once students reach that dollar cap, they can still take on a Grad PLUS loan to cover up to the “cost of attendance,” including living expenses (which are calculated by schools with no oversight). The scope of the Grad PLUS loan is significant—1.5 million borrowers hold an outstanding $83 billion in Grad PLUS loans to date.7 That’s a lot of taxpayer dollars that have gone largely untracked by the federal government to fund just one graduate loan program.

High debt totals for graduate programs are often considered just a part of the journey to a post-baccalaureate degree. Some argue that the students racking up very high amounts of debt are those in degree programs that will yield high returns on that investment, such as medical school or law school. Yet, in a recent report by the Urban Institute, researchers found that lower-earning fields like social work, clinical counseling and applied psychology, and mental and social health services are also leaving students with high graduate debt.8 Despite this potential for financial catastrophe, the federal government doesn’t require graduate programs to submit data on student borrowing. Much of the available data on graduate loans is collected via surveys, which do not allow us to pinpoint schools that could be recruiting graduate students to programs with little to no return on investment. This puts taxpayer dollars at risk by allowing nearly unlimited lending to attend graduate programs that are not held accountable in any way for students’ debt outcomes.

3. How much do low-income graduate students borrow?

Low-income students are more likely to take on higher debt levels as a general matter, which makes the lack of data on these students borrowing in graduate programs especially dangerous. On the undergraduate level, the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) requires undergraduate students to input personal and parental information that identifies a student's expected family contribution and whether they qualify for need-based aid, such as the Pell Grant. Receiving a Pell Grant can then be used as a proxy for identifying low-income students in undergraduate institutions and programs. This data is annually collected and rooted in IRS tax forms, ensuring a level of accuracy and transparency. Data on Pell recipients allows researchers and policymakers to identify where low-income students enroll and analyze their educational outcomes and return on investment across different institutions and programs.9

Graduate students fill out the FAFSA when they seek to receive federal loans, but they do not have to report parental income because they are not considered dependents. That means the low-income identity markers like Pell Grant eligibility are nonexistent for graduate students, and consequently the amount of low-income graduate students borrowing is not reported at the federal level. While no graduate students can receive Pell Grants, the Council for Graduate Schools reports that 46% of first-year graduate and professional students were recipients of the grant in their undergraduate studies, which indicates that low-income undergraduate students go on to enroll in graduate school in large numbers and may be taking on significant debt to do so.10 By not requiring schools to report comparable information across program levels, the current system of data reporting assumes that once students enroll in a graduate program, their previously documented income barriers are no longer an issue.

With data showing that low-income students are taking on higher amounts of debt for their undergraduate education, it's critical to know whether this same borrowing behavior exists in graduate education and how well institutions and programs are serving their low-income students. Greater data transparency will contribute to more accurate reporting on low-income graduate students and allow students to see which schools are likely to put them in a better position post-graduation. It would also allow a more accurate view of where taxpayers’ dollars are going, how they are being used to serve those needing help the most, and how their hard-earned dollars contribute to a better society.

4. How do race and gender interact with graduate student debt?

Research has shown that female, Latino, and Black students need to attain higher levels of schooling to receive earnings on the same level as white men with fewer credentials.11 The pursuit of those higher degrees has led to rising debt totals for many traditionally underserved students, and when looking at the intersection of race and gender, debt totals are even more pronounced. Black women on average accumulate $97,052 in total debt between undergraduate and graduate schooling—the highest of any group.12 Second to Black women are women of more than one race with $72,612 in debt, followed by Latina women at $66,112 in debt.13 Even with the limited information available, race and gender have major impacts on graduate student debt totals, particularly for women and borrowers of color. Yet federal data falls appallingly short in collecting and breaking down information on borrowing outcomes across demographics.

Without disaggregated data, it is impossible to fully identify, let alone rectify, disparities in student outcomes. Putting taxpayer dollars towards graduate programs that recruit and enroll underserved populations without a mechanism for understanding whether they provide true value or holding them accountable for how well they serve those students risks reproducing structural barriers these groups already face daily.

5. What are the repayment outcomes for graduate students?

One indicator of whether an institution or program is serving students well is loan default rate of past attendees. While flawed, the federal Cohort Default Rate intends to cut off taxpayer funding to undergraduate institutions that regularly leave large portions of their student population in default.14 A Brookings Institution report highlights that there is no official source that compiles graduate borrower outcomes, but past data collected showed that the default rate for graduate programs was 5% in 2009.15 But the low default rate may be misleading when exploring repayment outcomes due to a lack of publicly available data.

A Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report found that graduate borrowers not only have larger loan balances than undergrads, but they are also more likely to enroll in income-driven repayment (IDR) plans.16 IDR plans are available to students when their debt is high compared to their income. Borrowers enrolled in IDR plans have much lower default rates than students in the standard repayment plan, which could contribute to the lower default rates on graduate loans. And while graduate borrowers may boast a lower default rate, default is not the only negative outcome they may experience in repayment. In an IDR plan, the required payment amount might be lower than the accrued interest on the loan. This means that even if the payments are being made, the balance that a student owes can continue to rise. Graduate students borrowing more overall and enrolling in IDR plans create a perfect recipe for disaster if these students have high debt and low earnings—especially given what we know about borrowing patterns across race and gender lines. This does not make IDR a bad program for borrowers, but it can be a bad deal for taxpayers investing in graduate programs with poor outcomes and allowing new students to take out loans to enroll there. Additionally, these findings highlight that a lower default rate does not mean great outcomes from a program.

Despite these risks, no publicly accessible source for data on the repayment outcomes of graduate students exists. Improving transparency by providing annual disaggregated data collected by the federal government to the public would shed more answers to questions surrounding default, IDR enrollment, and repayment rates among graduate borrowers and demonstrate whether institutions are leaving graduate students with enough earnings to repay their student loans.

Conclusion

A federal data collection system with glaring gaps obscures the reality of graduate student borrowing and repayment outcomes. Disinterest in monitoring graduate education creates a system that gambles with taxpayer dollars, leaves the public without pertinent information to make informed decisions, allows graduate schools to escape accountability, and puts students at risk. We must do more to evaluate higher education in its entirety, including graduate programs, and ensure graduate students are getting a return on their educational investments.