Blog Published November 22, 2022 · 5 minute read

Democrats’ Path to 50% in Swing States & Districts

Aliza Astrow

After Democrats’ unexpectedly strong midterm showing, party leaders, advisors, and commentators are vigorously debating which voters carried them to victory in key races. Some point to youth voter turnout, which was high for a midterm election. Others point more broadly to a strong showing from the Democratic base.

Delving into the data, it is clear that while Democratic base turnout was not as depressed as it has been in some disastrous past midterms, it was still lower than Republican base turnout. In all competitive states, self-identified Republicans outnumbered self-identified Democrats. Democrats who won made up the difference in base turnout by winning Independent voters by wide margins, and even winning electorally significant shares of Republican voters in tough races. These results make clear that to win, Democrats cannot just appeal to their base but must persuade swing voters to support them over Republicans.

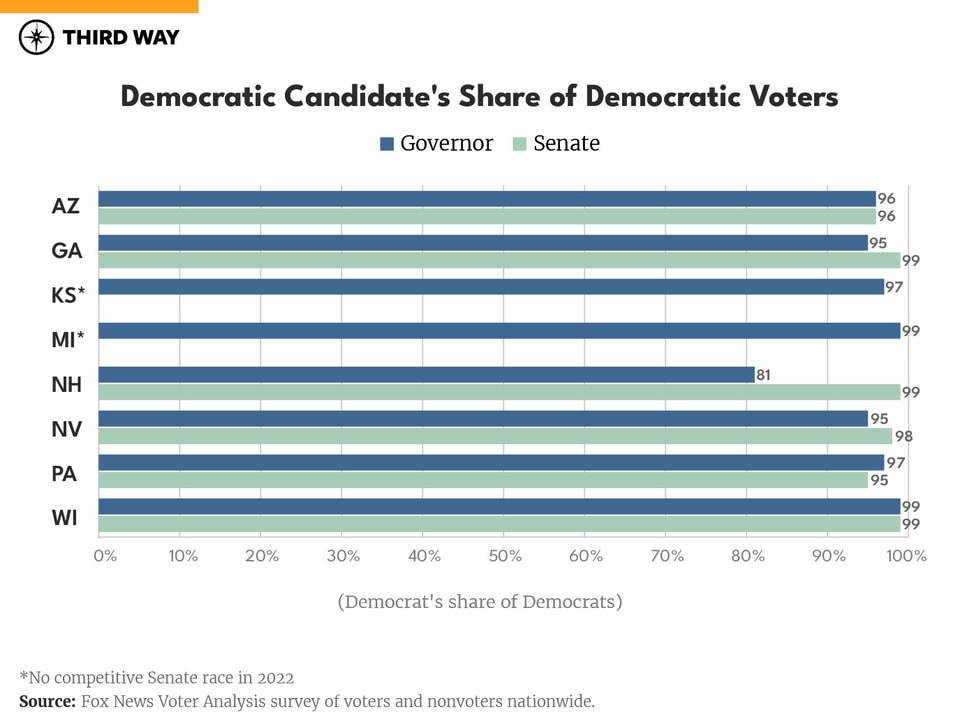

Democratic candidates cleaned up with Democratic voters.

Democratic candidates, unsurprisingly, won overwhelming shares of Democratic voters; consistently over 95% in competitive races. This was true among both Democrats who lost and won. Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer won 99% of Democratic voters, as did Senator Raphael Warnock, Governor Tony Evers, and Mandela Barnes. In Pennsylvania, Josh Shapiro won 97% of Democrats, while John Fetterman won 95%, along with Stacey Abrams in Georgia.

These candidates are demographically, ideologically, and stylistically diverse. The fact that Democratic voters remained similarly loyal to them indicates that Democratic voters were not wildly concerned with the specific ideological bents of their candidates, but rather would stand by Democrats against extremist Republicans in almost all cases.

Democrats who won were able to peel off some Republicans.

It might sound redundant to talk about Democrats’ high levels of support for Democratic candidates; in this era of high partisanship and low levels of ticket-splitting, it seems obvious that partisans would stand by their party. But looking at Democratic candidates’ shares of Republican voters, it is clear that in addition to consolidating their fellow partisans, Democrats wooed small shares of Republican voters to abandon their party’s candidates and cross the aisle.

This dynamic was particularly pronounced in competitive gubernatorial races. Laura Kelly won 19% of Republicans in Kansas and Josh Shapiro won 18% in Pennsylvania. Gretchen Whitmer and Katie Hobbs each won 11% of Republicans in their races. These relatively small shares of Republican voters were decisive in Kansas, Pennsylvania, and Arizona; had Republican voters stuck with the Republican candidates, Laura Kelly, Shapiro, and Hobbs would have lost (and infamous election-deniers Doug Mastriano and Kari Lake would be Governors-elect). Without these crossover voters, Whitmer would have hung on against Tudor Dixon by less than a point.

In the Pennsylvania, Nevada, and Georgia Senate races, the Democratic candidate won 8%, 7%, and 6% of Republicans, respectively. In Arizona, Mark Kelly won an impressive 13% of Republicans, which is particularly notable as partisanship tends to be higher in Senate than in gubernatorial races.

In Democrats’ losing campaigns, those candidates won smaller shares of Republican voters: in the Georgia governor’s race, Stacey Abrams won 4% of Republicans (2 points lower than Senator Warnock), while in Wisconsin Mandela Barnes won 3% of Republicans (half that of Governor Evers in his winning reelect). While these differences might seem small, in Georgia the difference in Republican vote share between Warnock and Abrams totaled 78,000 votes, while Warnock’s lead over Walker was only 36,000 votes. In Wisconsin, the difference in Republican support was also 78,000 votes, while the Senate race was decided by 26,000.

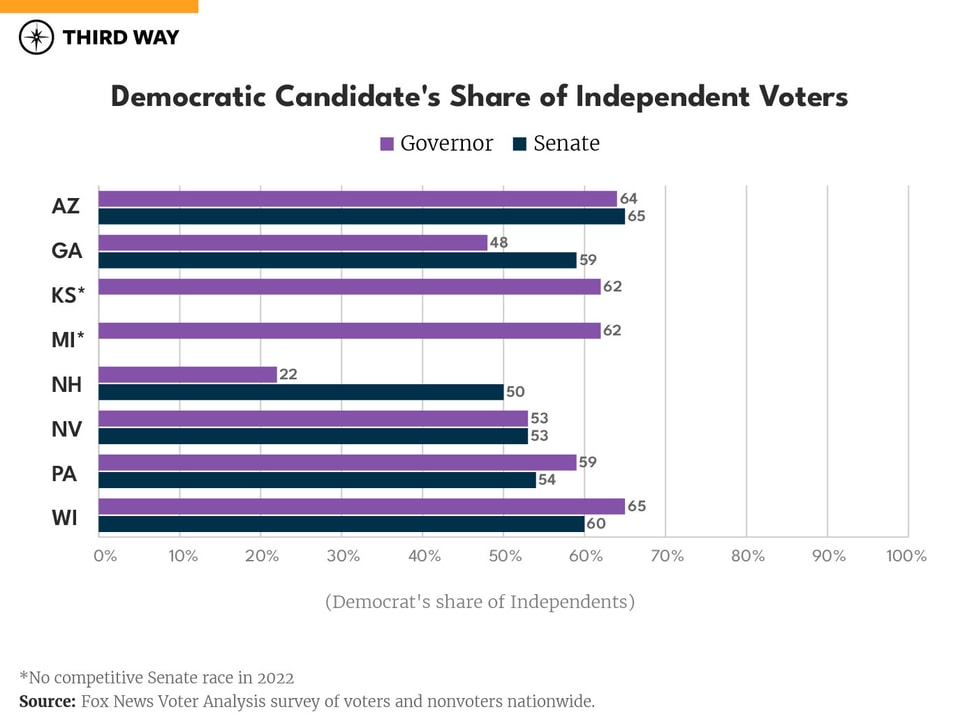

Independents’ support diverged between winning and losing campaigns.

Democratic campaigns that won and lost had significant gaps in levels of Independent voter support. Democrats won Independent voters in all competitive races, but their margins with these voters were key. The fact that Republicans could win even while losing Independent voters points to an important dynamic in this election; as mentioned above, self-identified Republican voters outnumbered Democratic voters. Democrats therefore had the tall order of needing to make up that difference by not just winning a majority of Independent voters, but by winning Independents by wide margins, while potentially peeling off some Republicans as well.

In the most glaring example of divergent fortunes, Abrams won Independent voters in Georgia by three points (48%-45%), while Warnock won them by 30 (59%-29%).

Other gaps were less pronounced but may have been decisive nonetheless; in Wisconsin, Tony Evers won Independent voters by 38 points (65%-27%). Mandela Barnes put up an impressive showing, winning these voters by 22 points (60%-38%). But had Barnes matched Evers’ margins with Independent and Republican voters, he would have finished the race at 51.7%, more than making up the difference needed to win a crucial Senate flip.

Conclusion

Democratic candidates’ success winning nearly all Democratic voters, as well as a majority of Independent voters, is a testament to the across-the-board strength of mainstream Democratic candidates this cycle. But what ultimately decided these races was not just Democrats’ ability to win a majority of Independent voters, but their ability to win these swing voters by wide margins, and to persuade some Republican voters to abandon Republican candidates.

These results have important implications for future Democratic campaigns. While it is important to celebrate and credit Democratic voters for turning out at solid rates in a midterm election, Democrats’ wins are primarily attributable to their ability to appeal to voters who do not always support Democrats. Winning these Republican-leaning and swing voters required Democrats to campaign in all parts of their states, not writing any voters off. It also required Democrats to craft appeals that kept their candidacies palatable to swing voters when Republican candidates were considered beyond the pale. In the end, mainstream Democratic candidates built a broad coalition to turn back their extreme right-wing opponents. If Democrats are to prevail in 2024, they will need to repeat this playbook.