Blog Published July 5, 2023 · Updated October 3, 2023 · 12 minute read

Q&A: What’s in the New Gainful Employment Rule?

Michelle Dimino

The Department of Education (Department) recently released its final Gainful Employment (GE) regulation. The GE rule addresses a requirement in the Higher Education Act that career education programs must “prepare students for gainful employment in a recognized occupation” to be eligible to accept federal student aid grants and loans.

The Department’s updated rule is the strongest yet, building on past iterations to ensure that federally-funded career training programs do not leave their students saddled with unaffordable debt or earning less than they could have without a postsecondary credential. It also introduces new financial transparency requirements that will apply to all institutional sectors and help more students understand the debt and earnings outcomes they can expect to see after attending a given higher education program. This memo addresses frequently asked questions about what’s in the new rule and how it will better protect the investment of students and taxpayers in postsecondary education.

Which college programs will be impacted by the GE regulation?

The GE rule applies to federally-supported career education programs—that means nearly all programs at for-profit institutions of higher education and non-degree programs, like certificates, at public and private non-profit institutions.

There are roughly 32,000 GE programs based on 2022 federal data. The majority (68%) of those programs are offered at public colleges, mainly community colleges, while 21% are offered at for-profit colleges and 11% at private non-profit institutions. Careers covered by GE programs include allied health fields like nursing and medical or dental assisting, cosmetology, massage therapy, welding, HVAC systems, and automotive technology, among others.

How does a program pass the GE thresholds?

To pass GE, career education programs must show that most of their graduates have affordable levels of student debt and receive a positive earnings premium from attending. The rule tests for this by examining two metrics: ratios of program graduates’ debt compared to their earnings, and a comparison of how program graduates’ earnings stack up against those of a typical high school graduate.

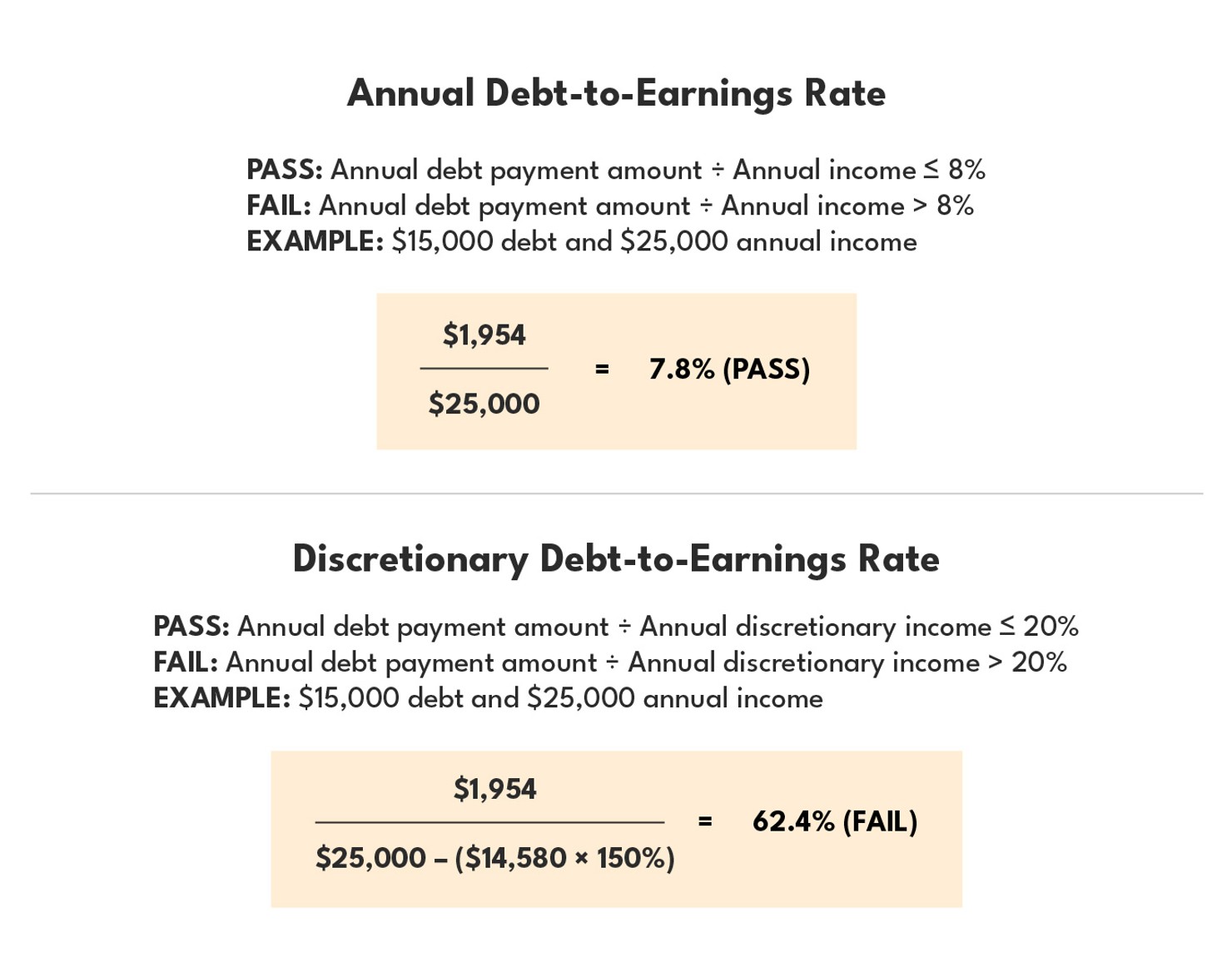

The two debt-to-earnings ratios in the rule zoom in on whether a program’s graduates can reasonably afford the annual debt payments associated with pursuing that credential. Programs pass when their graduates have an overall annual debt-to-earnings rate equal to or less than 8% or a discretionary debt-to-earnings rate equal to or less than 20% (meaning that of their income above 150% of the poverty guideline, less than one-fifth goes toward their debt payments).

Here's an example of what this would look like for a program where graduates took on $15,000 in student loans and earned $25,000 after completion. The annual loan payment amounts assume a standard 10-year amortization on a federal direct unsubsidized loan at a 5.5% interest rate. The federal poverty level in 2023 is $14,580. This example program passes the annual debt-to-earnings rate and fails the discretionary rate, but because failing both tests is the standard to fail GE, the program passes.

In a new provision to strengthen the rule, passing programs also need to demonstrate that at least half of their graduates experience an earnings boost from attending. This is assessed by comparing the median earnings of program graduates three years after completion to the median earnings of high school graduates aged 25 to 34 in the state where the program is located. A positive earnings premium indicates that the typical student could reasonably expect to make more by gaining this credential than they would if they never pursued postsecondary education in the first place, demonstrating that the program generally offers a financial return on investment to students and taxpayers.

What happens when a program doesn’t pass?

If a program fails both of the debt-to-earnings tests and/or the earnings premium for two of three consecutive years, it will lose access to federal student aid for a minimum of three years—meaning students will no longer be able to use Pell Grants or federal loans to attend that program. After three years of ineligibility, a program will be able to reestablish access if it has taken steps to improve program outcomes to acceptable levels.

GE is a program-level regulation, so other programs at the same institution that do pass (or that are not subject to GE) will not be affected and will maintain access to federal aid. Some schools may choose to voluntarily discontinue a program that is at risk of losing eligibility from failing the GE tests, which we saw under past versions of this rule. In that case, the school will also be subject to the three-year waiting period to reestablish eligibility for that discontinued program and will be prohibited from opening a similar program at the same credential level for a period of at least three years.

To be clear, an overwhelming majority of federally-funded career programs will pass GE. According to the Department’s data, about 1,800 of 32,000 eligible GE programs—just 5.6%—are estimated to fail one or both tests. Thus, the rule will concentrate on weeding out a relatively small number of bottom-of-the-barrel career programs that demonstrate persistently poor outcomes.

What happens to the students enrolled in impacted programs?

The Department anticipates that the new rule will protect 700,000 students who are enrolled in failing programs by ensuring they can connect to educational opportunities that will offer them stronger returns. Under the rule, schools that are at risk of losing their Title IV aid access the following year are required to notify their students to ensure that they are not blindsided and have an appropriate runway to make informed decisions. Since programs must fail two out of three consecutive years to face consequences, students whose programs are less than two years in length (like many career training certificates) are unlikely to experience any disruption to their education.

Students in longer-duration programs whose enrollment does overlap with their program’s failure will have several options. They can continue to enroll in that program without using federal aid (paying out of pocket or with employer benefits, for example) for as long as their school continues to operate it. They can also choose to use their student aid dollars to attend a different program in their field of study that passes the rule. The Department’s data indicate that more than 90% of students enrolled in failing programs have at least one other program that does pass GE within their field, credential level, and local geographic area into which they could transfer. Half of students attending failing programs have at least one alternative passing option in a related field of study at the same credential level within the same institution, and a quarter have more than one passing transfer option.

In its analysis of the rule’s anticipated impact, the Department also simulated how the enrollment of students receiving federal aid would likely shift due to students choosing to stay enrolled, drop out, or transfer from failing GE programs. After accounting for transfers to similar programs within the same institution or to similar programs at other nearby institutions, the Department estimates just a 1.2% decline in aggregate enrollment—but an increase in enrollment for certain sectors. The simulation anticipates that public community colleges stand to gain 27,000 students and Historically Black Colleges and Universities could gain 1,200 students from transfers to better-value programs at those institutions. While it is not ideal for a student to be attending a failing program in the first place, the rule would ensure that students have the information they need to make personal decisions about where they continue their studies—and that no new students spend their precious time and federal aid enrolling in them.

Which parts of this rule are new, and why were they added?

The earnings premium is arguably the biggest addition to the 2023 rule—previous iterations of GE only included the debt-to-earnings metrics. This additional test is important because it protects students from programs that leave their graduates making extremely low wages, no matter what level of debt they took on for the credential. As of 2017, over 1,700 career programs were leaving their graduates earning below the federal poverty line—but only 4% would have failed the original GE rule. Can a case really be made to say that taxpayer-funded programs are adequately “preparing students for gainful employment” if their graduates go on to earn less than they could have without that credential in hand, or struggling to put food on the table for their families?

Notably, the Department found that borrowers from programs that pass the debt-to-earnings tests but fail the earnings premium metric actually have higher odds of defaulting on their student loans than those from programs that fail only debt-to-earnings. Low-debt, low-earnings program borrowers have default rates that are 12.6% higher than borrowers who attended high-debt programs with passing earnings premiums. The high school earnings threshold adds a layer of critical nuance to the GE rule and works in concert with the debt-to-earnings measures to provide a balanced assessment of a program’s financial value to students and taxpayers.

The 2023 rule also includes new required financial disclosures for programs at all institutions, creating significantly greater transparency for the more than 16 million students attending over 123,000 non-GE programs. While the aid-eligibility consequences of failing GE will only apply to gainful employment programs, these new provisions will provide key information for prospective students on how all programs fare on the debt-to-earnings and earnings premium tests. The Department will set up a new website to house this information and other helpful data points, and schools will have to provide a link to the disclosure website to their prospective students. Students who are enrolled in or plan to enroll in non-GE certificate or graduate programs that fail the debt-to-earnings test will additionally be required to complete a form acknowledging that they have seen that information before their federal aid will be disbursed to the school. This new transparency component will empower prospective students and their families with better information on the cost and outcomes associated with the college options they are considering across the higher education system and provide useful data for institutions to pursue programmatic improvement—without any financial penalties for non-GE programs.

What about career fields that are notoriously low-paying, or that are dominated by women and people of color, who we know face discrimination in the labor market?

There are significant issues in how some professions are credentialed and compensated that disproportionately harm women, people of color, and women of color most acutely. These issues go beyond the scope of the GE rule, but they don’t negate the need for GE to ensure that graduates of federally-supported, career-focused training programs are not left earning poverty-level wages after attending. The worst possible outcome is for individuals and communities that face structural barriers and discrimination to be further harmed by predatory, low-quality GE programs that take advantage of students’ limited personal financial resources, squander their federal aid dollars, and leave them worse off than if they’d never enrolled. This rule creates a safeguard against that outcome.

Cosmetology is one frequently-cited example. As with prior iterations of the GE rule, taxpayer-funded cosmetology programs tend to fare poorly on the updated GE measures. But the field’s consistent underperformance on these financial value tests does not indicate a flaw in the rule—instead, it points to challenges in the industry that harm students and will require coordinated policy efforts to fix. Students looking to enter cosmetology fields have to meet state licensure requirements that typically include a high number of training hours, driving up their enrollment costs and debt. The jobs waiting for them on the other side often pay low wages, making repayment more difficult. But while it follows that many cosmetology programs will fail GE, the majority of cosmetology programs will not be affected by the new rule at all because they currently operate outside the federal financial aid system.

Research shows that graduates of non-federally-funded cosmetology programs typically pass required state licensure exams at similar rates but pay just a fraction in tuition, meaning that for many students, non-GE-eligible programs may present a better training option overall. To truly support students enrolled in cosmetology programs, many of whom are women of color, a strong GE rule is essential and should be complemented by the expansion of registered apprenticeships, investments in work-based cosmetology training programs, and state-level advocacy to prevent overinflation of the training hours required for licensure.

Doesn’t closing a program hurt students and schools?

Schools are not required to close a failing GE program—they just need to operate it without federal student aid for a minimum of three years. And the rule sets a clear ramp-up to that consequence, requiring programs to fail for two of three consecutive years before it takes effect. That means programs and schools will always have at least one year of advance warning, and they are required to notify their students if they are at risk of losing federal aid the following year. The limitation on access to student aid will not be sudden and should not come as a surprise to either schools or students.

Instead, GE can serve as an improvement mechanism for schools to consider the return on investment that students are getting from their programs. That’s what happened after the 2017 data release that showed how programs would have fared on the prior rule. Even with no consequences attached, schools voluntarily closed or altered hundreds of failing programs after examining the value proposition they were offering. GE gives schools another tool to assess the effectiveness of their career programs, and while that can lead to tough decisions about closing a program, it should absolutely lead to important conversations about how to improve training offerings to ensure they are aligned with workforce demand and are preparing graduates to succeed in their chosen career paths.

For their part, students will benefit from GE by experiencing reliably stronger outcomes from federally-funded career programs and having better information to select high-quality training pathways for their desired field. As a result, this new rule can help solidify and repair lagging public trust in higher education by making sure that all programs receiving taxpayer dollars are doing a good job serving both the students they enroll and the local labor markets those students enter once they graduate.

What’s next for the rule?

The Department received over 7,500 public comments on GE and the other proposed rules in the same package. After reviewing the submitted feedback, the Department released its final rule in September 2023, with implementation slated to begin on July 1, 2024.