Memo Published June 28, 2016 · Updated June 28, 2016 · 21 minute read

A Policymaker’s Guide to the On-Demand Economy

Paul Lapointe

Lately, it seems like Washington has been playing a game of Mad Libs. They were given the phrase “The ________ Economy” and have inserted words like Gig, Sharing, Platform, and On-Demand in a bid to label a new, innovative industry that has emerged in recent years. It doesn’t matter what policymakers call it, though. (For simplicity’s sake, we’ll refer to it as the On-Demand Economy.) What matters is that they understand the phenomenon before they legislate on it. In this report, we provide an overview of what lawmakers need to know about the On-Demand economy, who it impacts, and what ideas are out there to improve the experiences of the individuals and businesses that participate in it.

What types of players are in the On-Demand Economy?

Regardless of the moniker, the basic premise of the phenomenon is that technology platforms are connecting providers with consumers easier than ever before. Here’s what that means:

- Providers/Workers are the individuals performing a service or making a good. They include someone providing a ride home from a party (the Lyft driver), someone renting out their house (the owner of the Airbnb rental), someone who makes and sells art prints (the crafter on Etsy), or someone who fixes your backed-up sink (the plumber on Thumbtack).

- Consumers are the individuals (or companies) that are riding in the car, staying in the house, or purchasing the good.

- Platforms are the companies that create and manage the apps and websites to connect providers and consumers. The platform may also establish guidelines and rules for the transaction, facilitate the payment, or set prices.

What companies make up the On-Demand Economy?

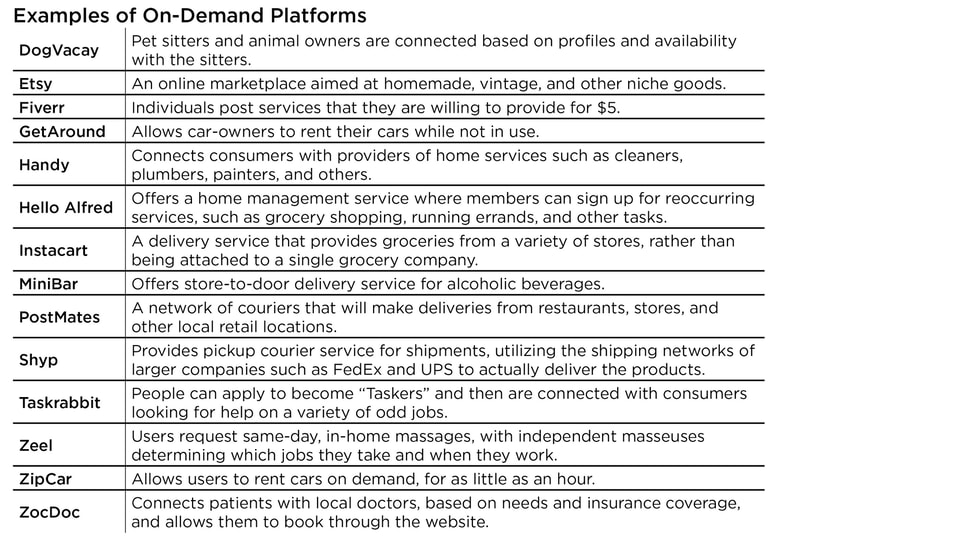

While most people have heard of Airbnb, Lyft, and Uber, there are actually dozens of On-Demand Economy platforms that take on a variety of forms—and new ones are popping up all the time. These platforms are operating in an assortment of industries and facilitate transactions in varying ways. The table below gives some examples of potentially lesser-known On-Demand companies.

It’s not just startups that are trying to find the next “Uber for X,” either. Large, established companies are wading into the On-Demand Economy and launching their own platforms. Daimler has been operating a car-sharing platform, car2go, since 2008.1 Just recently, General Motors launched their own car-sharing platform, GM Maven, and partnered with Lyft to let individuals rent cars for driving on the Lyft platform.2 And PriceWaterhouseCoopers recently announced that they are launching an online platform to connect freelance consultants with projects.3

While the constantly-growing number of companies in the On-Demand Economy might seem too disparate to identify, some organizations have suggested categorizing platforms based on key characteristics. For example, the JP Morgan Chase Institute released a report breaking On-Demand companies into two categories:4

- Labor platforms: Companies such as Uber and Handy match consumers with the labor needed to meet their demand (i.e. drivers or cleaners).

- Capital platforms: On the other hand, GetAround and Airbnb match consumers with capital assets that meet their demand (i.e. cars or places to sleep at night).

Thumbtack proposed a different categorization:5

- Commoditized platforms: Users request a good or service and the platform matches them with a provider that meets their demand. Instacart and Minibar are examples of commoditized platforms, since consumers select the products that they want delivered and the app determines who will deliver it.

- Marketplaces: Consumers can identify the provider that best meets their needs and expectations. Thumbtack and ZocDoc are examples of marketplaces where users can look at reviews and profiles to determine the exact provider that they want to conduct the work.

Finally, the Department of Commerce also came out with a classification which they call Digital-Matching Firms. The classification has four criteria: using a web-based platform as a peer-to-peer market; including a user-based rating system; allowing workers flexibility to set their own schedule; and, relying on workers to provide their own tools or assets if needed.6

Is the nature of work changing?

In short, we don’t know yet.

The rise of these new apps and platforms have led some to speculate that the fundamental way businesses and labor interact is transforming into more flexible, task-based arrangements. Some wonder whether this trend will start permeating into more and more industries. In this narrative, the traditional employer-employee model of labor is shrinking, and more people will derive income from a variety of sources, rather than working for one company at a time.

Others contend, however, that these projections are overblown, and that On-Demand Economy companies simply represent new versions of traditional independent contractor relationships (or are misclassifying workers). This school of thought points out that the On-Demand Economy comprises only a small portion of the total labor force, and that national statistics show no evidence of substantial changes in how businesses and labor interact.

Whether or not the idea of work is fundamentally changing, however, the On-Demand Economy is seemingly here to stay. First, we know that tens of millions of Americans are already engaging in the sector as either workers or consumers and that billions of dollars are being invested in it. This is big enough to warrant attention and consideration even if the industry doesn’t grow further. Second, it’s driving important conversations around how work is changing which impacts everything from worker protections to benefits. Third, features of the On-Demand Economy (such as increased consumer choice and flexible employee schedules) could permeate other industries even if the current technology platforms morph or end.

Because of that, the On-Demand Economy is absolutely something that policymakers should be striving to understand and starting to think about.

How many people work in the On-Demand Economy?

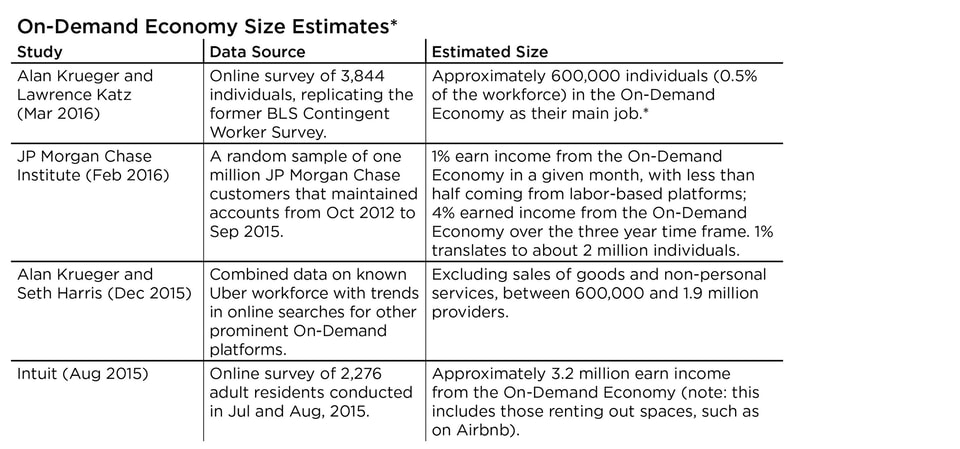

Precise counts are hard to come by because there is no comprehensive data looking at the industry and no consensus on exactly who should be included. The most common and robust federal government surveys on employment in the United States are just not tailored to get at the specifics of the On-Demand workforce. This leaves us with a series of privately administered surveys that give us estimates of the size of the On-Demand Economy workforce. (See table below.)

Overall, this data suggests that between 600,000 and 3 million Americans earn income from the On-Demand Economy. The lower end of that range encompasses those who primarily earn income from labor-based On-Demand platforms, and the higher end includes those that might earn income from multiple sources or from goods-selling platforms. The JP Morgan Chase data also implies that workers move in and out of the On-Demand Economy; thus, more workers may be impacted by it than just those working in it at any given time. It should be noted that sometimes higher figures are thrown out for these groups. These figures tend to also incorporate wider populations than this brief is looking at, such as traditional contractors and temporary workers not associated with On-Demand Economy platforms.

* Katz and Krueger, Farrell and Greig, Harris and Krueger, and Chriss7

The good news is that more comprehensive data should be available in the near future. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) recently announced that they would be reviving an updated version of the Contingent Worker Survey, with a goal of measuring the On-Demand workforce. The Contingent Worker Survey was a supplemental survey that BLS used to conduct every few years, but was discontinued in 2005. The BLS is expecting to conduct the survey again in 2017, which should provide policymakers with sorely needed data showing who is participating in this emerging market.8

Who is participating in the On-Demand Economy?

These same surveys, along with some others, have given us a profile of workers in the On-Demand Economy. Here’s what we know:

First, most providers in the On-Demand Economy work part-time and get more income from other sources then they do from On-Demand platforms. An Intuit study found that, on average, workers in the On-Demand Economy have three income streams, with the On-Demand Economy making up 34% of their total income.9 A detailed study of Uber drivers (conducted by Uber and analyzed by Alan Krueger, former Chairman of President Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisers) found that only 19% of drivers worked more than 35 hours per week, and roughly half worked less than 15 hours per week on the app.10 JP Morgan Chase found that workers in labor-based platforms earned about a third of their income from the platforms in months in which they used them, while those on capital platforms earned about a fifth of their income from the platform. Further, earnings from labor-platforms are more likely to replace earnings from other sources, while earnings from capital platforms are more likely to be supplementing income from other sources.11

Second, On-Demand platforms are most popular in large urban areas on the West Coast. Unsurprisingly, platforms are more popular in large West Coast cities than the rest of the country. For instance, 5.1% of adults earned income from the On-Demand Economy in San Francisco and 4.2% in Los Angeles (between October 2014 and September 2015), compared to the national average of 3.1%. Part of this could be that many of the most popular platforms have gotten their starts on the West Coast, although cultural preferences may be factoring in as well.

Finally, On-Demand providers are not there for lack of other options. Although On-Demand gigs may seem like they would attract people that can’t find jobs elsewhere, data suggests that Americans are more likely to become providers for other reasons. Top reasons include that they value the flexibility to set their own schedule or that they are looking to supplement income from elsewhere.12

What are some of the benefits of the On-Demand Economy?

The On-Demand Economy is already driving value to more than just the platforms and their investors.

Consumers: The fact that so many Americans have participated in these markets (around 20% according to one survey13 shows that consumers are finding value from these markets:

- Consumers get convenient and customized access to goods and services. Customers can just open their smart phone, pick what they want (and compare providers in marketplace apps), and choose when to get it.

- Consumers have a direct and easy method to provide feedback. After the transaction is complete, customers often are asked to rate the service. This gives customers more input into making the service better.

- Lower prices. In some industries, On-Demand platforms have reduced the transaction costs and overhead associated with connecting workers and consumers, thereby leading to lower prices.14

Workers: Individuals looking for work are also finding advantages to the On-Demand Economy. While a small portion start working as providers due to a lack of opportunities elsewhere, studies show the vast majority are opting in for other reasons:15

- Becoming a provider often does not have the same barriers that a traditional job has. The application and interview processes are typically simpler than a traditional job, and there are often unlimited openings for qualified individuals. (There are other barriers that exist in some platforms that do not exist in traditional industries, though, such as access to a qualified vehicle to be a ride sharing driver.)

- Providers are able to set their own schedule. Working a traditional job typically means working a specific schedule set by the employer. On-Demand platforms, though, allow providers to work irregular schedules that meet their needs. This makes the On-Demand Economy an attractive source of supplemental income for individuals with other jobs or transitioning between jobs. It also provides an opportunity for people that are unable to work set schedules, such as full-time caregivers.

Even policymakers have found value in the On-Demand Economy:

- Ride sharing may help with “last-mile” transportation. The last-mile refers to getting people from their homes to public transportation—be it a bus stop or train station—and can often be a prohibitive barrier for low-income people in using public transportation. Governments teaming up with these apps may be able to form partnerships that can cheaply connect people with public transit, as has been recently suggested.16

- On-Demand goods and services can provide new revenue streams to local governments. Some cities have started working with Airbnb, for example, to tax room rentals, providing those cities with new sources of revenues (although some of it may be recouping lost revenue from hotel traffic shifting to Airbnb). The lower prices in some of these markets may lead to more transactions taking place overall, as well, which could increase revenues in taxed markets.

What should policymakers be thinking about?

The On-Demand Economy is a hot topic, and many are encouraging Congress and other policymakers to take big, bold steps. These policymakers, though, first need to think through the different issues that the On-Demand Economy presents.

Worker Classification. One of the most prominent questions being asked when it comes to the On-Demand Economy is whether or not workers should be classified as independent contractors (as most are now) or employees. Our current classification system relies on a blurry and subjective line between the two categories, and the classification carries big implications for both providers and companies.

In a lot of ways, workers are similar to what is typically considered an independent contractor—they set their own hours, often use their own equipment (like cars), and can come and go from the labor force fairly easily. On the other hand, though, some workers share qualities that are typically associated with employees—they have little say in the prices charged to customers, they operate under the platform’s brand, and they sometimes have to adhere to policies that address how they complete their work. It is easy to see why different courts may reach different conclusions when it comes to classifying workers in the same app.

The implications of whether providers are employees or independent contractors are not small, either. Employees, as opposed to independent contractors, have more labor protections, such as:

- Minimum wage and overtime protections;

- Eligibility for unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation and Family and Medical Leave; and,

- Only have to pay the employee share of payroll taxes (independent contractors must pay the full payroll tax).17

For platforms, moving workers to employees would carry massive implications as well. For starters, costs would undoubtedly increase as a result of the benefits and protections. Additionally, ride-sharing apps would be required to reimburse their drivers for their mileage and gas, substantially increasing their costs. Along with this, platforms would likely have to adjust their business models if providers are classified as employees. Platforms that allow open access would need to start a more formal application and hiring process—if workers are entitled to benefits, you can’t allow anyone to just opt-in to being an employee. They would also need to rethink compensation and hours. If a worker is entitled to minimum wage and overtime, platforms could be reluctant to allow them to choose how many hours to work or which jobs to take.

As a result of this debate, an uncertainty has arisen that may be further straining the platform-provider relationship. Platforms and others have claimed that this threat of their providers being classified as employees has resulted in them not providing services and resources that they otherwise would (e.g.: professional development, tax assistance, tax withholding, optional benefits packages, and insurance pooling) in order to prevent courts from being able to use it against them in proceedings.18

This worker classification battle is not new or unique to the On-Demand Economy. It is a debate that has been ongoing for decades, and it will continue to go for as long as the line between employees and independent contractors is blurry and carries substantial implications. The discussion being brought up now, though, presents a great opportunity for policymakers to rethink the system—and several proposals to retool it have been released (as discussed later).

Benefits and Protections. A related issue to worker classification is around the benefits that workers receive. For decades, there have been certain things that policymakers have decided every American should have: protection from racial discrimination, retirement income in the form of social security, and more recently health care through the Affordable Care Act. There may be other protections and benefits that lawmakers believe should be universal, or at least easier to access. These may include protection from gender and sexual orientation discrimination, other insurances such as disability, unemployment or wage, and workman’s compensation, private retirement contributions, and paid sick and family leave. For other benefits, policymakers may want to encourage, but not require them, such as paid vacation time, worker training, and advanced scheduling. The discussion around the On-Demand Economy and a more transient workforce presents an opportunity for lawmakers to ask this question and consider major changes to what all workers should receive—not just those in traditional forms of employment.

When policymakers start thinking about new benefits, there are some important questions to consider. Saying that workers, or all independent contractors, should have paid sick leave or disability insurance is one thing—figuring out how to implement it is a completely different question. Will the platforms be required to provide the benefits based on hours worked or jobs completed? Will the platforms or consumers be required to pay a fee that goes into an account that providers can use to purchase these benefits themselves? Will a tax be assessed on the transactions and the government will provide the benefits through a centralized administrative system? These are important questions that need to be considered, and the right answer may be a combination of different approaches for different benefits and protections.

Tax Filing. For an individual accustomed to working a typical job and filing taxes as a W2 employee, taking on a side gig with an On-Demand Economy platform brings with it a substantial increase in tax filing complexity. Many of these workers have little to no experience with self-employment taxes, quarterly filings, or understanding which of their work-related expenses are deductible. This complexity is compounded by the fact that many On-Demand workers do not earn enough to trigger a 1099, meaning they are responsible for tracking and reporting everything on their own. A recent report by the Kogod Tax Policy Center found that this leads to confusion, under-reporting, penalty payments for missing quarterly estimates, and a lack of proper recordkeeping.19

Local Regulations and Taxes. Some argue that the tech-based start-ups are achieving their success in part by avoiding state, city, or county regulations in areas like zoning, licensing, consumer safety, or local, industry-specific taxes. For instance, ride-sharing companies may not face the same regulations that taxi companies do in areas like licensing, insurance, and background checks. Similarly, home-sharing platforms may not face the same tax, health, and zoning requirements that traditional hotels must comply with. Applying substantially different regulations to competing businesses has the potential to distort markets and give some companies advantages over others. As policymakers think about whether specific regulations should be extended to On-Demand companies, an important consideration is whether the regulation actually furthers the public interest. If not, it may be better to roll the regulations back to create parity, rather than creating a roadblock to innovative companies.

Additionally, if On-Demand transactions take business from traditional industries, the tax base for local governments may decrease, reducing funding for investments in areas like road infrastructure or tourism services. To address this, some municipalities have worked with companies like Airbnb to register and apply hotel taxes to transactions that take place on the platform.

Access. Although it is less talked about than other issues, an important consideration is who can access the opportunities created by the On-Demand Economy. Typically, participating as either a worker or consumer requires a smartphone or internet-connected device, meaning that the digital divide prevents millions of Americans from taking advantage of these new opportunities. While 85% of 18 to 29 year olds own a smartphone, only 27% of those older than 65 do. Of even more concern is the divide between different income levels. Only half of people with incomes lower than $30,000 a year own a smartphone, compared to 84% for those making more than $75,000 a year.20 While owning a smartphone may not be the only barrier to being employed through one of these platforms, increasing access to smartphones would both directly connect people to job opportunities through the platforms, and also provide them with the benefits of consuming these services (such as access to last-mile transportation).21

Recent Notable Events in the On-Demand Economy

Lyft and Uber lawsuits, arbitration hearings, and settlements. The disagreement over how On-Demand providers are classified has already made its way to courtrooms and arbitration hearings. This has led to the two companies coming to settlements with their drivers in specific areas. The companies have agreed to make financial and process concessions as part of these settlements, but have retained the independent contractor model in each.22

On-Demand companies switch to W2 labor. While the debate over classification has continued, some On-Demand companies have switched all or part of their provider pool to employee status, deciding that it was the right model for their companies. Platforms that have made the move include Hello Alfred, Luxe, Shyp, and Instacart.23

NYC Uber drivers partner with labor group. Uber drivers in New York City have formed the Independent Driver’s Guild under the International Association of Machinists. The new Guild will work with Uber to give drivers more of a voice in policies and decisions that affect them, although it will not engage in collective bargaining.24

Local ballot initiatives. Voters in San Francisco rejected a ballot initiative that would have placed stricter regulations on short-term rentals, and was commonly seen as aimed at On-Demand Economy platform Airbnb. More recently, voters in Austin, Texas rejected a ballot initiative that would have overturned regulations requiring ride-sharing drivers to undergo fingerprint-based background checks administered by the Austin Transportation Department. In response to the regulation being upheld, Uber and Lyft announced that they would no longer operate in the city.25

What are some of the proposals out there?

Over the past year, many organizations and individuals have proposed ideas on how to address the concerns of the On-Demand Economy, most of which have focused on worker classification and provider benefits. Below are short summaries of some of the more prominent proposals.

- In our Ready for the New Economy Report, Third Way called for a portable, privately-run accumulated benefits package in addition to a minimum pension. In this, providers would receive pro-rated contributions to an account which they could then use to purchase benefits on their own, based on their individual needs.

- Alan Krueger and Seth Harris, both noted academics and former Obama Administration officials, released a plan through the Hamilton Project calling for the creation of a new class of workers, the independent worker, which lies between an employee and independent contractor. The independent worker would receive some of the benefits and protections, but not all, that employees currently receive but independent contractors do not.

- The R Street Institute proposed the creation of a safe harbor that would encourage, but not mandate, companies to create safety nets for their independent contractors. To incentivize companies to do this, the burden of proof in employee classification cases would shift to the worker as long as the benefits plan met certain criteria.

- Nick Hanauer, of Second Avenue Partners, and David Rolf, of SEIU, proposed creating a shared security system. The proposal would require employers to provide prorated benefits to all workers, regardless of classification or status.

- President Obama included demonstration funding for portable retirement packages in his FY2017 budget.

- Sen. Mark Warner and Gov. Mitch Daniels are co-chairing a future of work commission, with the goal of understanding how to best support workers and companies in the 21st century economy. The commission will be working to cultivate ideas that address work in the On-Demand Economy.

Conclusion

Almost two-thirds of Americans own a smartphone26 —giving them the opportunity to request a ride, order a repairman, or rent an apartment virtually anytime and anywhere. This On-Demand Economy is obviously upending the traditional consumer experience—and it also has the potential to rethink how work is performed in America. Our hope is that policymakers can embrace this economic change, work to understand its implications, and continue to devise smart policy, when needed, that allows for continued innovation, all while protecting consumers and workers.