Memo Published September 26, 2017 · 7 minute read

GE by the Numbers: How Students Fared at Programs Covered Under the Gainful Employment Rule

Tamara Hiler & Wesley Whistle

Takeaways

According to data released earlier this year, more than 1.1 million students graduated from programs covered by the Department of Education’s gainful employment (GE) rule. This rule was finalized in 2014 to ensure that career education programs (like nursing, cosmetology, or welding, to name a few) and for-profit programs are worth their cost to the students who attend them. Like any student seeking a postsecondary education, students attending a GE-covered program do so primarily to better their chances of economic mobility and secure a better future for themselves and their families. But a new Third Way analysis of the gainful employment data collected and made publicly available for the first time earlier this year shows that for a shocking number of graduates from these programs, this goal was never realized.

- 1 in 10 graduates covered by the rule attended programs at schools that failed the gainful employment metric in 2015.

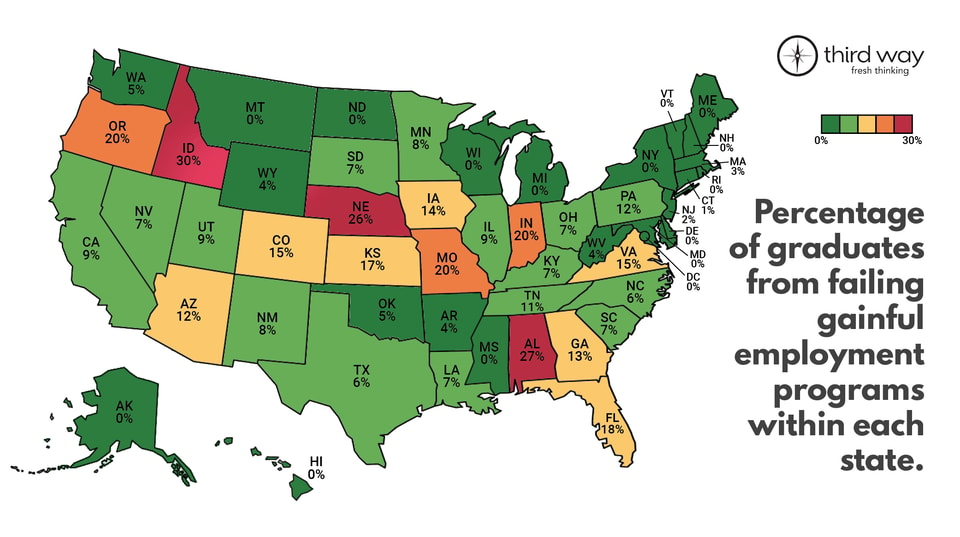

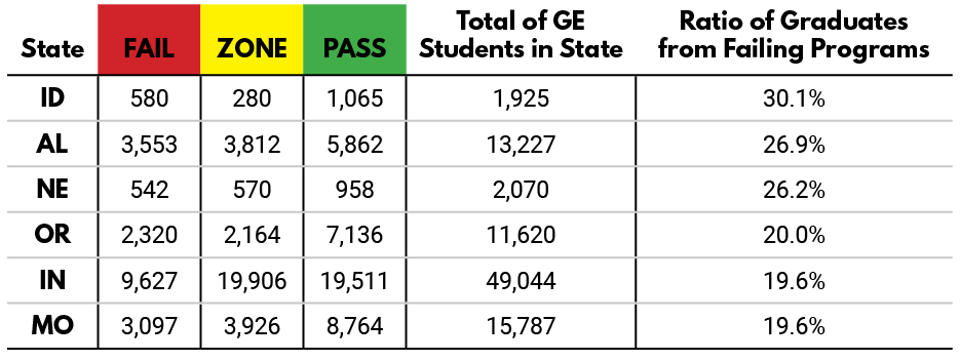

- In six states, 1 in 5 graduates attended programs that failed the gainful employment metric.

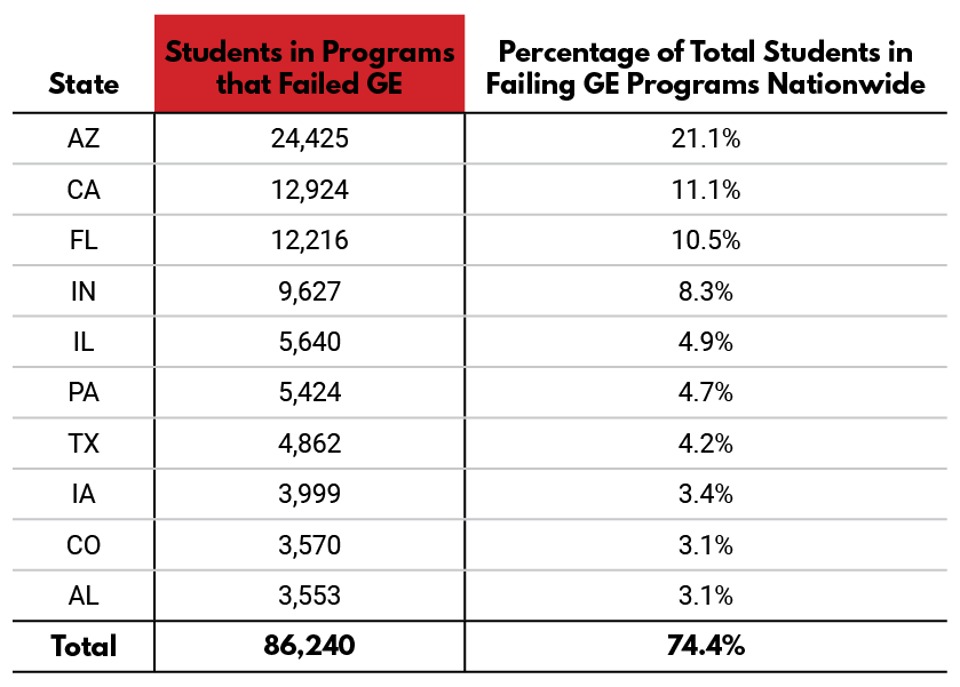

- Three-quarters of graduates from failing programs are concentrated in schools from just 10 states.

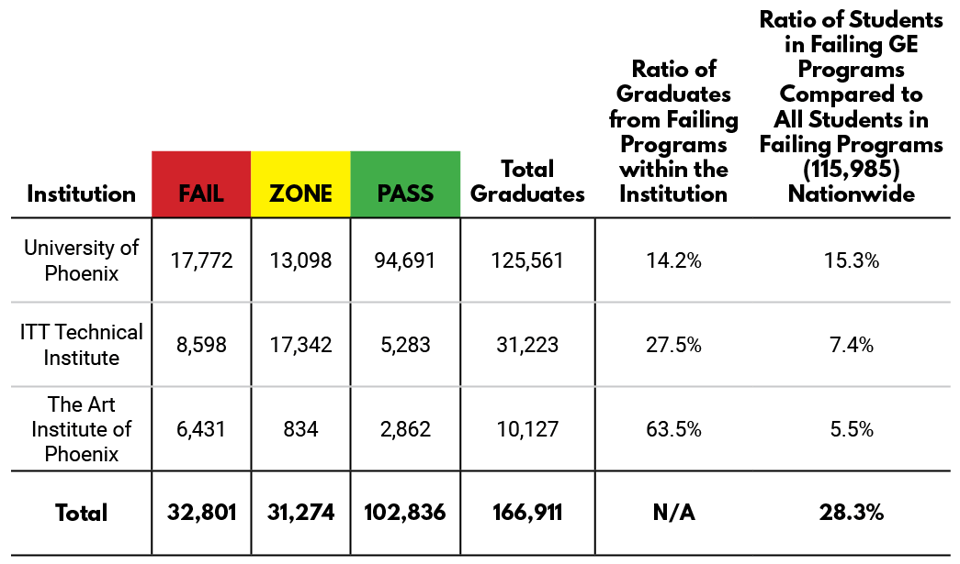

- Nearly 25% of students graduating from failing programs came from just three institutions.

Background: How Gainful Employment Operates

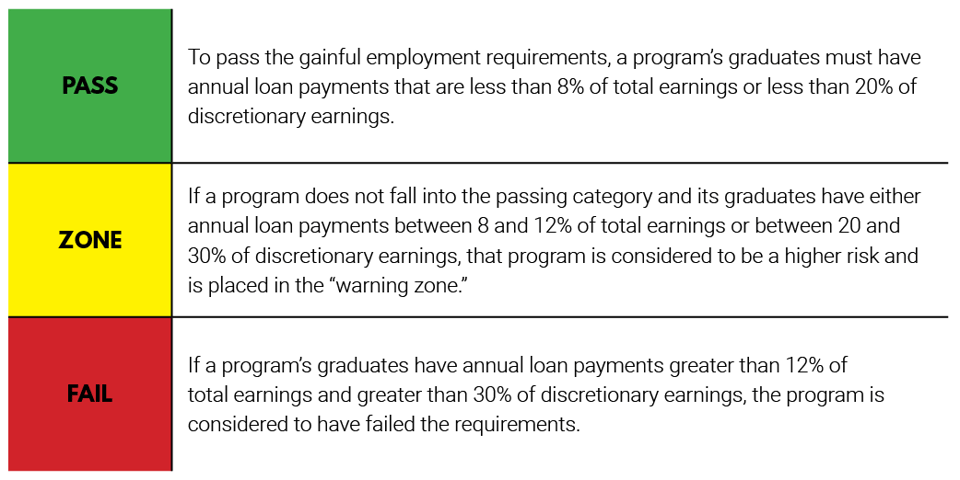

The gainful employment rule was put in place by the Department of Education in 2014 to enforce a requirement in the Higher Education Act that any program at a for-profit institution or certificate program at a public or private non-profit school, “prepare students for gainful employment in a recognized occupation.”1 To do this, the gainful employment rule measures the debt-to-income ratio of graduates using a tiered “fail,” “warning (zone)” and “pass” system to flag for students which programs may become ineligible for federal funding in the near future (See Appendix A for a full description of this breakdown). If most graduates from a certain program fail to make a high enough salary to sufficiently make payments on their loans in two out of three consecutive years, that program is supposed to lose access to Title IV federal student aid dollars (taxpayer-funded grants or loans). In essence, the gainful employment rule weeds out the programs that provide the least value to students by cutting off failing programs from federal funds—playing a crucial role in protecting both students and taxpayers from wasting money on degrees and credentials that fail to make students better off.

Findings: Graduates from Failing Programs are Concentrated in a Handful of States and Institutions

The first set of gainful employment data released earlier this year has already proven to be a powerful consumer protection tool, and when analyzed together with enrollment data, it also reveals the number of students that have graduated from programs that fail to meet the rule’s debt-to-income thresholds.

1 in 10 graduates attended programs that failed the gainful employment metric.

Out of the more than 1.1 million students who graduated from GE-covered programs in data released earlier this year, 10%—or 115,985 students—graduated from programs that failed the gainful employment test, with another 20%--or 243,242 students—graduating from programs that fell in the warning zone. This means that nearly one-third of all graduates attended GE programs that were flagged as offering limited earnings potential and unmanageable debt.2 And it’s important to note that these are students who actually graduated from these programs—meaning they passed the requisite classes they needed to earn a credential or degree. If you added in the huge number of students who didn’t complete these programs, the earnings outcomes would likely look even worse.

In six states, 1 in 5 graduates from GE-covered programs earned degrees or credentials that failed the gainful employment test.

Six states appear to have a significantly higher proportion of students graduating from failing gainful employment programs than the nation overall. The data reveals that in Idaho, Alabama, Nebraska, Oregon, Indiana, and Missouri, 20% or more of the GE-graduating population finished programs that failed to meet the debt-to-earnings thresholds. At the top of that list sits Idaho, a state with less than 2,000 students graduating from career education programs. But a high number of those students are coming from cosmetology programs whose graduates are not earning enough to pay down their educational debt. Indiana also boasts high percentages of students in failing programs, as it served as home base for ITT Technical Institute, an institution that has since closed due to its abysmal outcomes for students.

Seeing such variation across states—both large and small—underscores the reality that our higher education system is a patchwork when it comes to quality. That is why we need federal rules like gainful employment to ensure that programs based out of any state are meeting a minimum threshold of quality for consumers and taxpayers alike.

Three-quarters of all graduates of failing programs are concentrated in just 10 states.

A closer look at the data also reveals that 86,240 of the 115,985 students (74%) that attended failing GE programs hailed from programs concentrated in just 10 states—Arizona, California, Florida, Indiana, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Texas, Iowa, Colorado, and Alabama. In large part this is due to large for-profit institutions being headquartered in one state but running satellite campuses or online programs in others—like behemoths University of Phoenix and Grand Canyon University both claiming Arizona as a home base. However, it is concerning to see how institutions from just a handful of states can have such a pervasive negative effect on the lives of students across the country. For example, Florida had only 5.8% of the country’s GE-covered graduates, but still boasted more than 10.5% of students from failing programs nationwide.

Three institutions accounted for a quarter of all graduates from failing GE programs.

Lastly, a more granular look at the data reveals that of the 115,985 graduates from programs that failed the gainful employment test in the first year of reported data, 32,801 of those students—or 28%--came from programs housed within just three institutions: The University of Phoenix, ITT Technical Institute, and The Art Institute of Phoenix. This is especially striking given the fact that the GE data is collected and measured at the level of each program (not the whole institution), so the concentration of failing programs within a few schools seems to indicate institution-wide failure to provide good outcomes to students.

Luckily, ITT Tech has since shuttered its doors after the federal government ended its ability to offer federal financial aid to new students based on the recommendation of ITT’s accreditor.3 And the University of Phoenix has already begun the process of closing down failing programs in light of their investors’ reactions to this publicized outcomes data.4 These examples illustrate how having transparency and accountability mechanisms like the gainful employment rule in place can convince accreditors and investors to shutter programs that are actively harming students’ chances at economic success.

Conclusion: Keep Gainful Employment Protections in Place

The first set of gainful employment data released earlier this year makes clear the powerful role this consumer protection tool can play in warning students away from the lowest-value programs on the market. Yet new attempts to delay implementation and loosen enforcement mechanisms are undermining the rule, harming the millions of students who continue to enroll in poorly-performing programs each year.5 With $130 billion in federal taxpayer funding going directly to institutions of higher education each year, the federal government must continue efforts to expand—not limit—the kind of transparency and accountability the gainful employment rule has already started to bring in its debut year. As we continue to encourage more students to earn a postsecondary credential or degree in order to compete in the 21st century economy, it is imperative that we ensure that the time and money they invest in order to do so will be well-spent.

Appendix A

For a more detailed description of the gainful employment rule, click here.

Download the Data

Download the data from this report.