Memo Published November 19, 2020 · 18 minute read

How a Biden Administration Can Guarantee Apprenticeships for All

Kelsey Berkowitz

As President-elect Joe Biden rightfully warned, “Because technology continues to change, American workers…will need opportunities to continue to learn and grow their skills for career success and increased wages in the 21st century economy.”1 The need for postsecondary skills was true before COVID-19 and is even more apt now. Over 11 million Americans are unemployed, and the country has lost over 10 million jobs.2 While some of those jobs could come back when the pandemic stabilizes, many won’t. And the jobs that do come back may look different than before the pandemic, since the coronavirus will likely lead companies to increase their use of technologies like automation and artificial intelligence.3

All of this suggests that workers may need to upgrade their skills or gain new ones to thrive in a post-COVID labor market. To help them do that, we need what President-elect Biden has called for: “education and training beyond high school that will give hard-working Americans the chance to join or maintain their place in the middle class, regardless of their parents’ income or the color of their skin.”4 A key part of that promise must be expanding apprenticeship opportunities to everyone who could benefit from them.

In this memo, we lay out why apprenticeships should be a significant part of a Biden Administration, what the Biden campaign has already called for, and how to expand that vision to guarantee apprenticeships for all.

The need for apprenticeships in a Biden era

President-elect Biden’s platform is built on the foundation that we must create more good jobs and “give America’s working families the tools, choices, and freedom they need to build back better.”5 That’s where apprenticeships come in. Apprenticeships are a proven workforce training model—one that lets people earn money while learning valuable, in-demand skills. Apprentices earn paychecks from Day 1, with wages increasing as apprentices progress through their training. Upon completing their program, apprentices earn a national, industry-recognized credential, and people who complete apprenticeships typically earn $70,000 a year.6

But while apprenticeship participation has increased over the last decade, they still have not caught on in the United States in the same way they have in European countries. In 2019, the United States had 633,476 active apprentices across nearly 25,000 programs—less than 1% percent of our population.7 By contrast, if we had the same apprenticeship participation rate as England or Germany, that number would rise to roughly 5 million. If we had the same participation rate as Switzerland, the United States would have over 8 million apprentices.

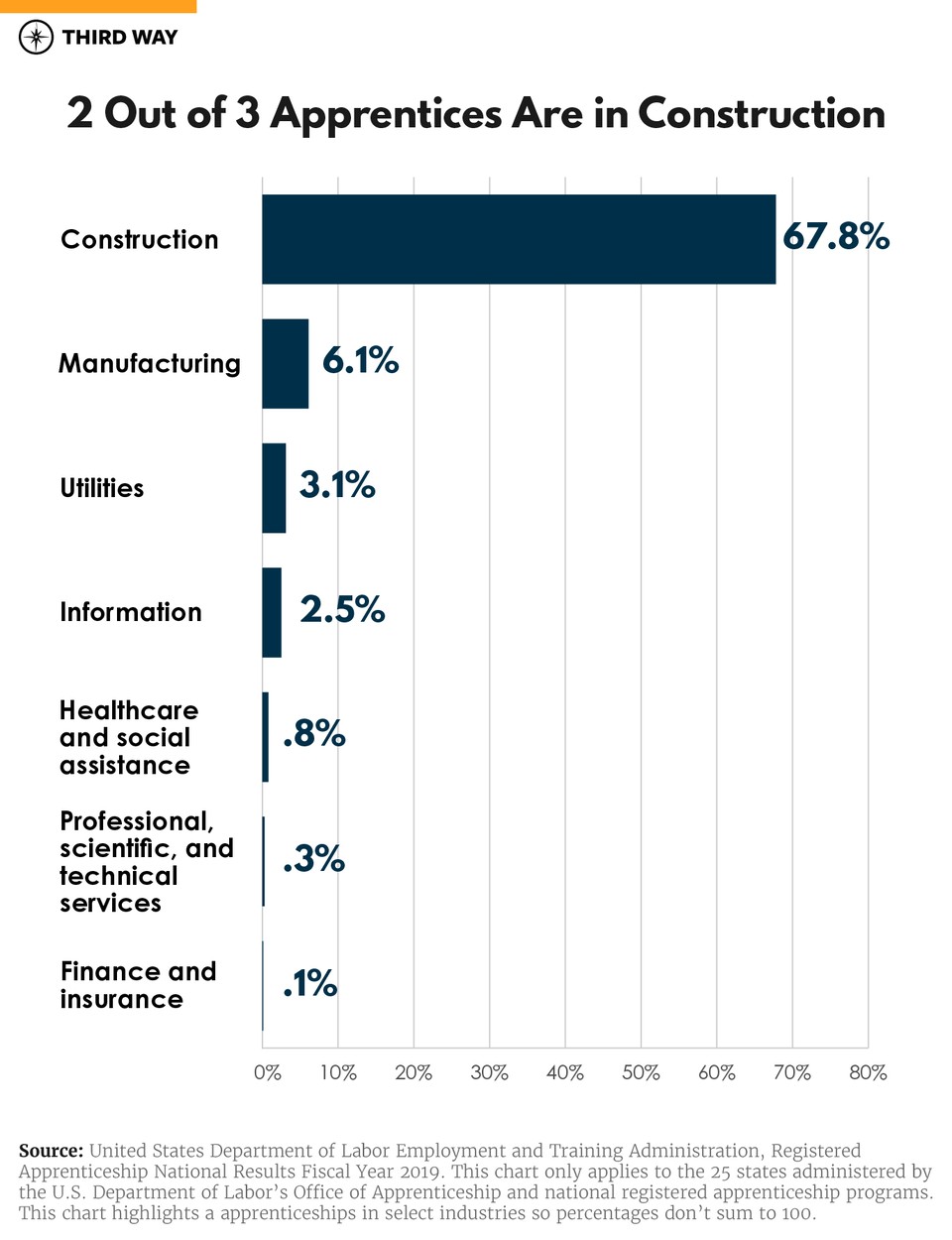

Apprenticeships also remain rare in new or growing industries such as information technology, health care, financial services, and utilities. This is despite efforts to boost apprenticeships in these industries, and despite projected worker shortages in them. Fewer apprenticeship programs in these industries mean fewer pathways for people looking to enter those fields. Even for traditional industries like the building trades, which have longstanding apprenticeship programs, applicants can be waitlisted for multiple years.8

There is also a severe lack of awareness in this country about the opportunity apprenticeships provide. Many workers don’t know about the benefits of apprenticeships, or that apprenticeship programs can exist in a range of industries. Many businesses don’t know how apprentices can help them create a source of skilled workers for the future or how to create a registered apprenticeship program. There are also funding issues—from financial and resource barriers for employers to lack of dedicated, long-term funding to bolster apprenticeship expansion efforts at the state level.

It should be no surprise then that this valuable tool isn’t available to enough people. In 2019, women made up roughly half the labor force but just 9% of active apprentices and 12% of new enrollments.9 On top of this, women apprentices are more concentrated in certain industries with low pay, such as childcare and hospitality. Black and Hispanic apprenticeship participation is similar to those groups’ share of the labor force, but people of color are often concentrated in certain industries. For example, Hispanics are underrepresented in STEM apprenticeships for occupations like engineering technicians and cybersecurity specialists.10 Black apprentices are paid less than other demographic groups, earning just $14.35 per hour upon completing their apprenticeships in FY 2017, compared to $26.14 per hour for white apprentices.11

Biden’s Plan for Education After High School

Over the past year, President-elect Biden pledged to provide two debt-free years of community college or high-quality training programs to all Americans looking to gain new skills, from recent high school graduates to mid-career workers. Importantly, this program would be a “first-dollar program” that would allow students to use other forms of aid, such as Pell grants, for other necessities like books or living expenses. To improve student retention and completion of credentials, Biden also proposed a new grant program to assist community colleges in using evidence-based practices like expanding career advising, smoothing transfer processes, and improving remedial education.

President-elect Biden also pledged to make a $50 billion investment in high-quality workforce training. These funds would go toward:

- Promoting community college-business partnerships that would identify skills that are in-demand in a community and create training programs that lead to industry-recognized credentials.

- Increasing the number of apprenticeships in the United States by strengthening the Registered Apprenticeship system and partnering with unions to expand apprenticeships in fields like technology and manufacturing.

Biden also aims to strengthen the registered apprenticeship system through the following steps:

- Creating a special Manufacturing Communities Tax Credit to encourage projects that revitalize manufacturing facilities, particularly projects that employ workers trained via registered apprenticeship programs; and

- Investing in pre-apprenticeship programs that are partnered with a registered apprenticeship program.

To help jobseekers and ease lifelong learning, Biden proposed:

- Making individual career services like one-on-one career coaching universally available to all workers;

- Providing Unemployment Insurance benefits for the duration of reskilling programs; and

- Increasing funding for community-based organizations that help women and people of color access high-quality training and job opportunities.

How Biden can guarantee apprenticeships for all

The Biden Administration can expand economic opportunity and help everyone onto good-paying career paths by building on his campaign platform and adopting an Apprenticeship Guarantee—anyone who wants an apprenticeship should have access to one, and every apprentice should have access to the wraparound supports they need to complete their programs. To make the Apprenticeship Guarantee a reality, a Biden Administration can build on his existing platform with the following steps:

1. Expand apprenticeships in every state through Apprenticeship Institutes and new Apprenticeship Block Grants.

One of the challenges states have faced in expanding apprenticeships is the lack of consistent, dedicated, and to-scale funding from the federal government to support those efforts. While the US Department of Labor has provided grant funding to states to expand apprenticeship opportunities, this funding is at the discretion of the Department and states must submit competitive grant applications for it. There is currently no source of apprenticeship funding for states that is permanent and guaranteed every year.

Congress should provide states with greater consistency and certainty about the funding they will receive each year for apprenticeship expansion efforts so they can engage in longer-term planning and implement longer-term strategies. It should also boost funding levels to ensure apprenticeship opportunities exist for everyone who wants one, no matter who they are or where they live.

To accomplish this, the federal government should establish Apprenticeship Block Grants, an annual formula grant program to provide apprenticeship expansion funds to states. Part of this funding will go towards the creation of Apprenticeship Institutes in every state. These Institutes will function as hubs in each state’s apprenticeship system—proactively engaging employers, workers, technical colleges, unions, and other organizations that make apprenticeships work. They would market apprenticeships to employers, help employers register and launch new apprenticeship programs, match young people and mid-career workers to apprenticeship programs, and guide apprentices to success by connecting them to supports like childcare.

States would be able to use federal funding for other purposes as well. For example, the federal government could allow funds to be used for things like:

- Creating or expanding equity intermediaries focused on expanding apprenticeship opportunities for groups that have traditionally been underrepresented in apprenticeships;

- Boosting apprenticeships in nontraditional industries by creating or expanding industry intermediaries;

- Creating marketing campaigns on the benefits of apprenticeships targeted toward employers and potential apprentices.

- Funding third-party impact and cost-benefit evaluations of apprenticeship programs to learn what works in apprenticeships and to have more evidence of success when marketing apprenticeships to employers.

- Creating employer-to-employer apprenticeship ambassador programs for nontraditional industries;

- Expanding pre-apprenticeship or youth apprenticeship programs;

- Improving transitions from pre-apprenticeship programs to full apprenticeship programs or from youth apprenticeships to postsecondary institutions;

- Providing career exposure opportunities to help prospective apprentices select the apprenticeship pathway that’s right for them;

- Developing online related technical instruction for apprentices in rural areas;

- Aligning apprenticeships with 2- and 4-year college credit; or

- Other uses that the state deems necessary to expand apprenticeships.

A sustainable, flexible source of funding will help states expand apprenticeships to more people in more places. Each state’s economy and mix of industries differs, and each state may have unique needs when it comes to expanding apprenticeships. Governors, state workforce officials, and state legislators have the best understanding of what’s needed to expand apprenticeships in their states and are in the best position to engage with employers and industry associations.

Earlier this year, House Education and Workforce Committee Democrats proposed National Apprenticeship Act reauthorization legislation that would authorize formula funding for state apprenticeship agencies each year ($75 million in FY 2021, increasing by $10 million each year through FY 2025). The Biden Administration should make it a legislative priority to work with the Committee to reintroduce this legislation if it is not enacted this year, build support for it in both chambers, and shepherd it across the finish line. A Biden Administration could also start with an initial tranche of funding in its FY2022 budget request, and Congress should follow on with long-term dedicated funding.

2. Help workers complete their training with an Apprentice Support Voucher program.

Currently, apprentices often must cover expenses like childcare, transportation, work clothes, and sometimes work supplies in order to complete their programs. But not everyone can access and afford these expenses, presenting barriers especially to women, low-income workers, and people of color. For example, female apprentices report struggling to find and pay for childcare as a barrier to success.12

The Biden Administration should create an Apprentice Support Voucher program to help apprentices pay for necessary expenses, enabling everyone to complete their training. For example, small and medium-sized employers may not be able to help apprentices with transportation or work supplies, so the federal government could step in and provide assistance. Apprenticeship sponsors or intermediaries would apply to the Department of Labor’s Office of Apprenticeship on behalf of an apprentice or cohort of apprentices, specifying a dollar amount needed to cover eligible expenses. Apprentices could also be allowed to apply independently, and applications could be allowed on a rolling basis in the event emergency assistance is needed. Funding could be distributed to apprenticeship sponsors to purchase necessities on behalf of apprentices, or funds could be provided directly to apprentices through a flexible spending account debit card that would be approved to cover qualifying expenses.

A Biden Administration could start with an initial tranche of funding in its FY2022 budget request, and Congress should follow on with long-term dedicated funding. The federal government could also provide matching funds when states commit their own funding.

Further, as part of his Build Back Better plan, Biden pledged to cap child care costs for low- and middle-income families at 7% of income and to expand after-school, weekend, and summer programs for school-aged children. The Biden Administration can go a step further and make child care free for all parents enrolled in apprenticeships or other job training programs. Alternatively, the Biden Administration can boost funding for child care subsidies and guarantee subsidies for parents in apprenticeships or other training programs.

3. Make the registered apprenticeship system easier for employers to use.

Many employers lack experience setting up and administering apprenticeship programs. The process to register an apprenticeship is burdensome and bureaucratic, requiring employers to complete tedious paperwork. On top of this, employers often lack the flexibility to design apprenticeship programs to fit the way their industries work. For these reasons, many choose not to register their apprenticeship programs or choose not to set up any apprenticeship program at all.

A Biden Administration can partially address this through an executive order. To start, the Administration should call on the Department of Labor to do a top-to-bottom assessment of its apprenticeship registration process and reporting requirements to see where hurdles can be eliminated or streamlined, and where the Department can handle requirements that have up until now been placed on employers. For example, USDOL registers programs in half the states, and state governments register programs in the other half. The Biden Administration can direct USDOL to assess areas where it can improve federal-state coordination on registration and reporting requirements, which will help apprenticeship sponsors that operate programs in multiple states. The Biden Administration can also call on USDOL to assess its apprenticeship data infrastructure and identify areas where that infrastructure can be streamlined or improved so it’s easier for employers to use and better integrated with state data.

As part of this, USDOL should assess whether there are sufficient off-the-shelf resources for employers to take and customize for their needs—such as apprenticeship agreement templates, marketing materials, or sample curricula for particular occupations—and whether existing resources are accessible for employers. The Biden Administration could convene or survey industry associations and employers to gather input from a diverse array of industries, since concerns and experiences in nontraditional industries may differ from those in more traditional ones. The Administration could direct USDOL to create permanent Industry Apprenticeship Advisory Committees for industries like health care, advanced manufacturing, and energy so employers have an open line of communication with the Department.

Alternatively, the Biden Administration can work with Congress to pass legislation directing USDOL to undertake such a review, report to Congress within six months on areas where the Department can streamline registration and administrative requirements for employers, and develop a plan to do so. On top of this, the Biden Administration and Congress could direct USDOL to develop a “frequent flyer” program so employers that already have approved programs can go through a simpler, fast-tracked registration process.

4. Help small and medium-sized employers create more apprenticeship programs.

The costs of starting an apprenticeship program will differ for each company, but lack of capital can be a significant barrier to creating apprenticeship programs, particularly for smaller employers. These start-up costs can involve things like developing curricula and purchasing equipment. While large companies might be able to afford the upfront investment in apprenticeships, small- and medium-sized businesses may not be able to do so without some form of financial assistance.

Many states already provide employers with tax credits and other financial incentives to encourage them to hire apprentices. Creating a National Apprenticeship Tax Credit would ensure that this support is available to employers across the country. An alternative idea would be to provide low-interest Federal Apprenticeship Loans to small and medium-sized employers. Offering assistance in the form of loans would have the added benefit of reaching companies sooner than tax credits and, unlike grants, loan dollars can be recovered and reused.

Under a Federal Apprenticeship Loan, the Treasury Department and Department of Labor would partner to directly administer low-interest apprenticeship start-up loans to employers with fewer than 1,000 employees. Employers could receive loans of up to $10,000 for each new apprenticeship position the employer plans to create, repayable over four to eight years depending on the length of the apprenticeship. Loan rates could be tied to the federal funds rate. Additionally, loans could be partially or fully forgiven in certain circumstances—for example, for successful programs created in under-resourced areas or those that have good recruitment and completion rates for women and people of color.

If the Biden Administration wanted to offer a National Apprenticeship Tax Credit instead, it could offer eligible employers (those with fewer than 1,000 employees) a $1,000 tax credit for each registered apprentice on its payroll for at least the majority of the calendar year. Similar legislation, the Leveraging and Energizing America's Apprenticeship Programs (LEAP) Act (H.R. 1660), has been introduced in Congress by Rep. Frederica Wilson (D-FL).

5. Expand equity in apprenticeships.

We need to do more to ensure apprenticeships are accessible for groups that have been historically underrepresented as well as people who face barriers to employment, including women, people of color, returning citizens, older workers, military members and spouses, veterans, and people with disabilities.

The Women in Apprenticeship and Nontraditional Occupations (WANTO) program is a US Department of Labor program that awards federal funding to community-based organizations that help increase women's employment in apprenticeship programs and nontraditional occupations, like advanced manufacturing and energy. This funding helps organizations develop pre-apprenticeship, apprenticeship, and skills-training programs as well as provide supportive services to women to help them succeed and remain in apprenticeship programs and nontraditional occupations. Funding for the program was $4 million in 2020, an increase from $1.5 million in previous years.

The Biden Administration should increase funding for the program to at least $40 million as part of its FY2022 budget request and should award grants to more organizations across the country—at least one in each state and territory. The Women in Apprenticeship and Nontraditional Occupations Amendment Act (H.R. 4933), sponsored by Reps. Marc Veasey (D-TX) and Brendan Boyle (D-PA), would expand the WANTO program to do just that. The bill would also allow grantees to use the funds to help pay for transportation and childcare costs. In expanding the WANTO program, the Biden Administration should also award more funding to organizations that will help women enter nontraditional industries such as information technology and financial services.

The Biden Administration can also make smaller grants available to community-based organizations that don’t currently assist women apprentices but want to build their capacity to do so. The WANTO program typically provides grants to only a handful of community-based organizations each year. Increasing the number of organizations capable of doing this work could help address the stark gender gap in apprenticeship participation.

The Biden Administration should also issue an executive order directing the Department of Labor to do a rigorous assessment of equal opportunity regulations to identify areas where those regulations can be improved or where enforcement can be strengthened. As part of this process, the Biden Administration should direct USDOL to seek input from organizations that have focused on and advocated for increasing the participation of marginalized groups in apprenticeships. The Biden Administration should also provide USDOL with sufficient resources and staff to ensure employers are following equal opportunity regulations.

More effort is also needed to ensure people of color and people who face barriers to employment have access to apprenticeship programs in diverse industries. The Department of Labor has previously awarded grant funding to the states to expand industry intermediaries, which focus on boosting apprenticeships in nontraditional industries, and equity intermediaries, which focus on boosting apprenticeship participation among underrepresented groups. In addition to providing formula funding to the states that will allow them to create and expand equity and industry intermediaries, the Biden Administration can take the following steps to boost diversity in apprenticeships:

- Provide bonuses to states that hit equity benchmarks on top of their Apprenticeship Block Grant allocations. For example, states would receive bonuses when they have apprenticeship participation and completion rates that mirror the diversity of their state populations or workforces, when racial, ethnic, and gender wage gaps have been closed, and when within-industry demographic gaps have been closed or at least narrowed.

- Require employers in industries where women and people of color are concentrated, such as childcare, to pay apprentices a living wage.

- Create a grant program similar to WANTO that will provide funding to community-based organizations (CBOs) working to help marginalized groups succeed in apprenticeships, such as people of color, returning citizens, and people with disabilities. These CBOs would partner with state Apprenticeship Institutes, equity intermediaries, and other stakeholders to connect these groups to apprenticeships through outreach, pre-apprenticeships, and supportive services.

- Ensure people in pre-apprenticeship and youth apprenticeship programs have access to wraparound supports and financial assistance for things like rent and utilities if needed.

- Provide apprenticeship funding to the states based on factors like minority share of the state population, number of low-income residents, share of population living in poverty, and share of state population without postsecondary credentials. Provide additional funding to states with greater racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in apprenticeship participation or completion, and require this additional funding to go toward efforts to boost equity and diversity in apprenticeships.

Conclusion

The pandemic has left millions of Americans out of work, and many will need help regaining their footing in the job market. President-elect Biden has recognized the valuable role apprenticeships can play in helping Americans access high-quality skills training and economic opportunity. Through an Apprenticeship Guarantee, the Biden Administration can extend the promise of apprenticeships to everyone.