Memo Published February 2, 2023 · 13 minute read

How a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism Can Strengthen US Competitiveness, Workers, and Climate Efforts

John Milko

Takeaways

- A US carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) that assesses fees on imported products based on their embodied carbon intensities would reduce emissions while generating billions of dollars for decarbonization investments in the US

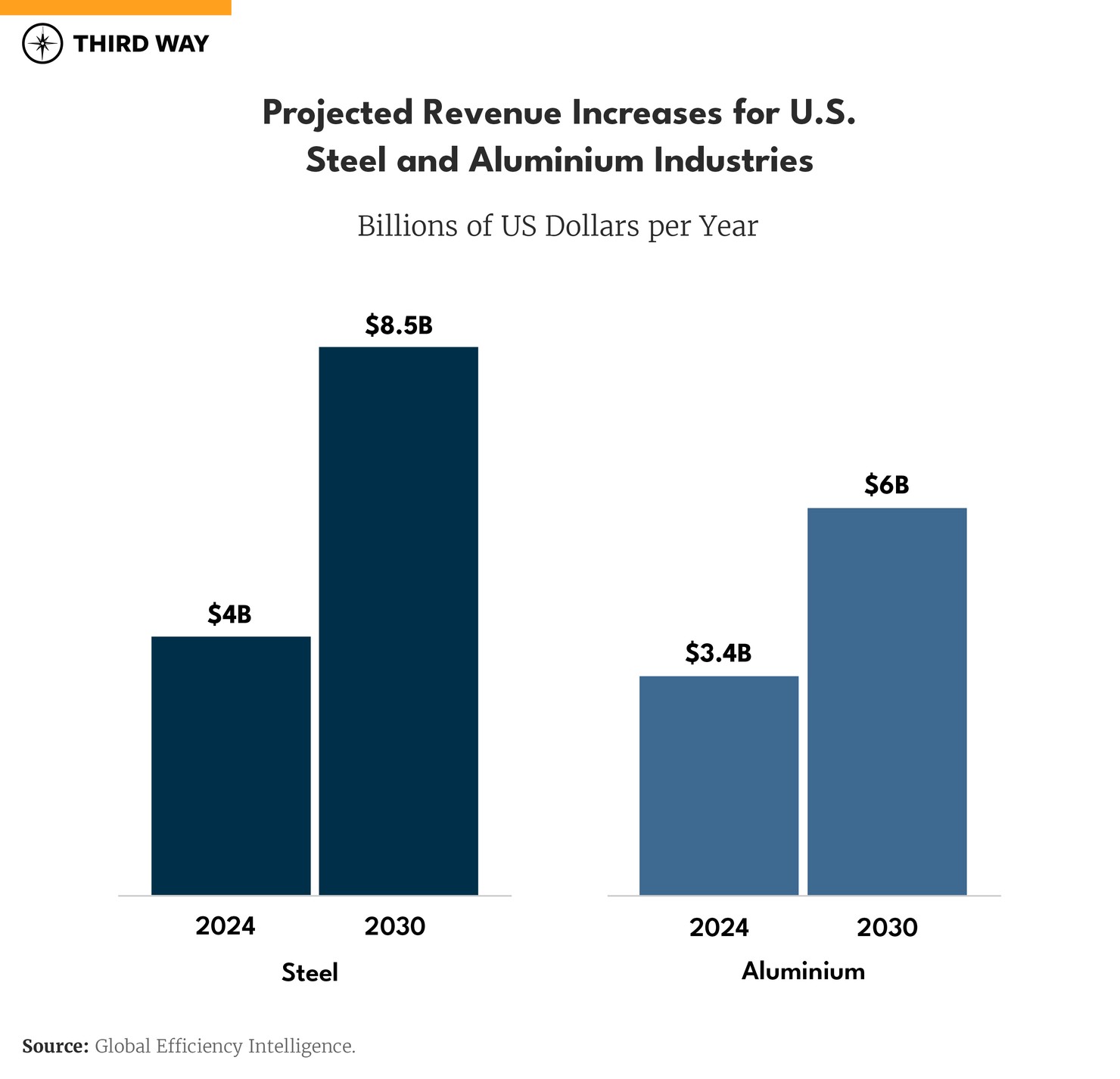

- Implementing a CBAM in the US would make domestic steel and aluminum more price competitive, reduce imports, and help American steel and aluminum producers capture an additional $8.5 billion and $6 billion of their markets, respectively, by 2030.

- The US can leverage new resources provided in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to establish an effective CBAM that bolsters US manufacturing while incentivizing other countries to cut their industrial emissions in kind.

Trade Policy as Climate Policy

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), signed into law by President Biden in August 2022, marked a major turning point in US policy efforts to stem the worst effects of climate change. The law will deploy public capital and attract substantial new private capital to scale up clean energy infrastructure and commercialize promising new technologies that will help decarbonize every sector of the economy, including industry.

The industrial sector accounts for 30% of total US emissions and is projected to soon pass transportation and power as the most carbon-intensive sector in the economy.1 While policies included in the IRA—including various industrial tax credits, direct federal investments, and low-carbon materials procurement programs—will curb emissions associated with the manufacturing of industrial products like steel and aluminum, there are additional actions the US can take to address these major sources of climate pollution.

In a new report, Global Efficiency Intelligence (GEI) looked at how the US can leverage trade policy to reduce emissions in the steel and aluminum sectors.2 Governments and trading blocs including the European Union (EU), United Kingdom (UK), and Canada are at various stages of developing trade policies that impose fees on imported materials that do not meet specified environmental standards. This framework, known as a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM),3 could effectively limit carbon-intensive imports while improving the cost-competitiveness of domestic, comparatively cleaner goods.

Both Democratic and Republican members of Congress have also supported the idea of implementing a CBAM in the US, but until now, we have not had an idea of its potential impact on major US industries, like steel and aluminum. GEI found that such a trade policy could mitigate the amount of carbon-intensive imports while raising significant revenue that can be reinvested to further decarbonize US manufactured goods. As global demand for cleaner steel and aluminum continues to grow, the US has an opportunity to capitalize on its recent decarbonization policies to bolster domestic industries while advancing its climate goals by implementing a CBAM framework.

Global Production and Trade of Steel and Aluminum

In order to better understand the impact of a CBAM framework on the US steel and aluminum industries, GEI cataloged the average embodied carbon of these materials, or the total amount of emissions associated with their manufacture and use, among industrialized countries across the world.4 The US ranked second lowest for average embodied carbon intensity among major steel producers, and ninth among primary aluminum producers. When secondary aluminum production is considered, the US aluminum industry ranks as one of the least carbon intensive because around 80% of the aluminum produced in the US is low-carbon secondary aluminum.5 Roughly all steel and 66% of aluminum products imported to the US originate from countries that, on average, produce these materials with higher embodied carbon intensity. Consequently, these US industries could benefit from a trade system that places a cost on embodied carbon and adjusts the price of imported goods accordingly.

There are both economic and environmental justifications for implementing a border carbon adjustment to reward low-emitting facilities. Manufacturers in advanced industrialized nations or trading blocs, like the US and E.U., are often subject to more stringent environmental regulations and ambitious emissions goals than competitors in other nations. Without a global price on carbon, manufacturers are not fairly rewarded for adhering to stricter pollution standards and making facility improvements that lower the embodied carbon of their products. Levying import fees on carbon-intensive products rewards sustainable production practices and incentivizes companies to make decarbonization investments in order to stay competitive in a global marketplace.

By making foreign manufacturers compete on the basis of both cost and climate impact, a CBAM can narrow the “carbon loophole” that threatens to delay global progress on tackling climate change. The carbon loophole refers to the practice of more developed countries with services-oriented economies importing goods to functionally offshore carbon-intensive manufacturing processes. This allows them to claim lower national emissions without addressing major sources of climate pollution.

For instance, the US carbon footprint is 16% higher if calculated on the basis of emissions consumption, which accounts for the emissions of imported goods, rather than production.6 And the US is hardly alone in this practice. An estimated 22% of global carbon emissions are embodied in imported goods.7 A CBAM can limit the extent to which countries can outsource their emissions by making carbon-intensive imports less cost-competitive than cleaner, domestically-produced options. This would help drive both domestic and foreign investment in manufacturing technologies that lower industrial emissions.

CBAM Impact

In GEI’s analysis, a CBAM covering steel and aluminum goods based on emissions-performance would cut US consumption emissions while raising significant revenue that can be largely reinvested back into those domestic industries for further decarbonization efforts, per the directive in Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s (D-RI) Clean Competition Act (S. 4355).8 The bill would also invest a smaller portion of the revenue to help industrial decarbonization in developing countries.

To construct this analysis, GEI assumes that the US sets embodied carbon thresholds for specified sectors, based on the average intensity of domestically-produced materials and above which both imports and US-made materials are subject to fee.9 If implemented in 2024 with a $55 price per ton on carbon (increasing 5% each year through 2030), this CBAM policy could reduce total US steel imports by 26% in 2024 and 55% in 2030 by making cleaner, domestic steel more cost-competitive. As a result, US producers, who operated at only 82% capacity in 2021, can increase production to accommodate most of the new demand caused by a reduction in steel imports and increase revenue by a projected $4 billion in 2024 and $8.5 billion in 2030.

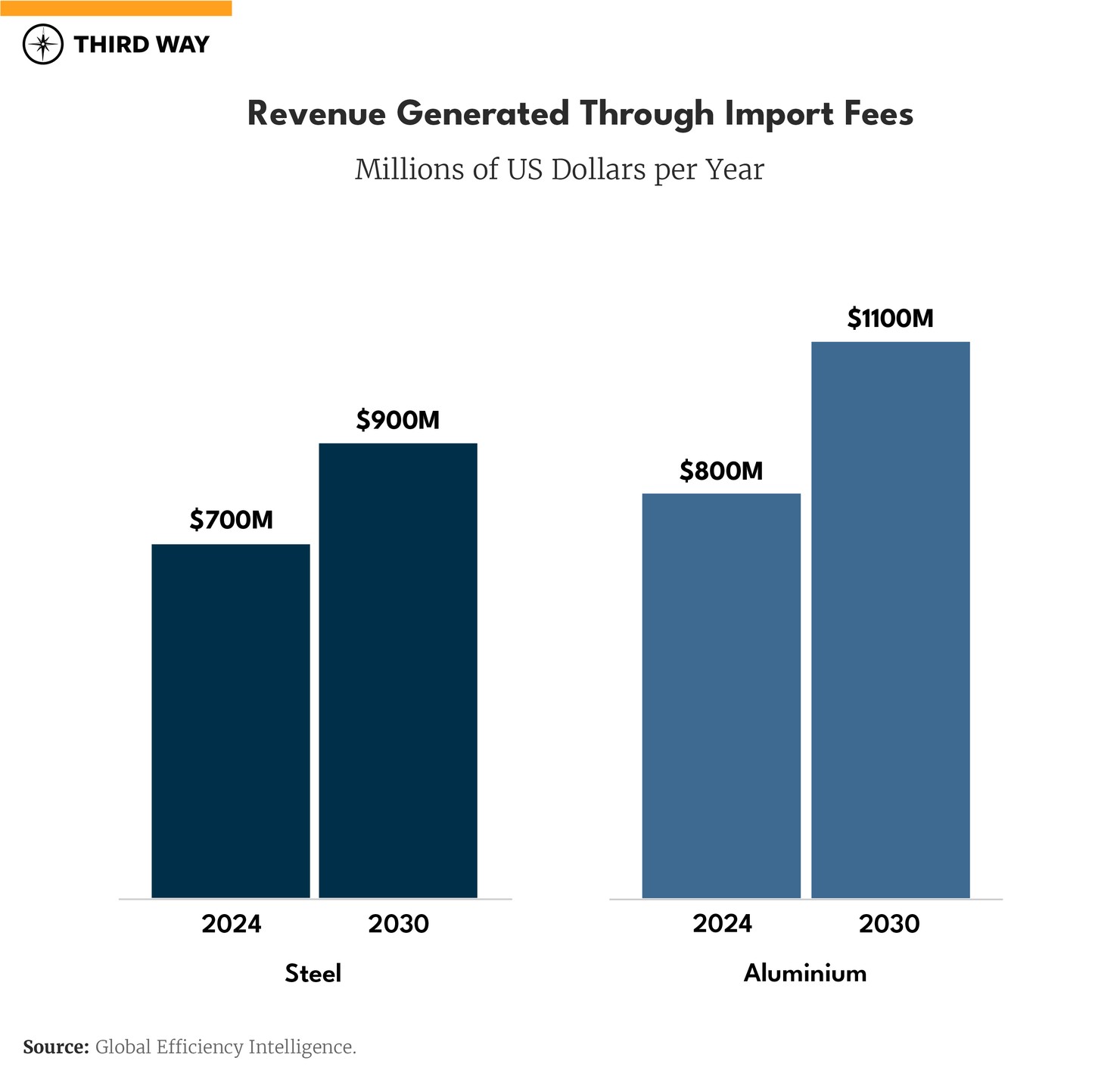

The resulting shift in demand for cleaner goods could also reduce the total embodied carbon of steel imports by 15% in 2024 and 27% in 2030. Furthermore, it could raise between $1.9 to 2.5 billion annually for further steel decarbonization investment over this timeframe, 37% of which would come from fees on imported steel and the remainder from US steel companies.10 In short, this policy would allow US companies11 to capture a greater share of the US market while raising more money for capital investment than it extracts from US companies, assuming 75% of total revenue is distributed among domestic companies for industrial decarbonization investment.12

For aluminum, the results are similarly beneficial to the competitiveness of US industry and overall industrial decarbonization efforts. Under the same CBAM framework, GEI estimates that aluminum imports could decrease by 31% in 2024 and 55% in 2030, reducing the total embodied carbon of aluminum imports by 44% in 2024 and 59% in 2030 and increasing revenue for US companies by a projected $3.4 to $6 billion annually between 2024 and 2030. It could also raise between $1 to 1.4 billion annually over this timeframe, 81% of which would come from fees on imports, providing an additional pool of funding for further decarbonization of US aluminum production.

This assumed framework, like the Clean Competition Act, assumes the provision of export rebates for US producers. Because the goal of a CBAM is to limit carbon leakage by taxing consumption emissions, materials manufactured but not consumed in the US should not be subject to the domestic fee, if applicable based on carbon intensity (i.e., domestic products with higher than average embodied carbon). Without export rebates, manufacturers could simply relocate to a jurisdiction without a carbon tax to avoid paying the domestic fee.

However, there is some debate regarding whether such rebates constitute an illegal subsidy under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules and whether countries would respond to a US CBAM by enacting retaliatory tariffs on US exports.13 For steel and aluminum, the impact of potential countermeasures are likely negligible, in GEI’s estimation. Imports from Canada and Mexico would largely meet the embodied carbon threshold in this scenario, as established by the average carbon intensity of US materials, based on the average carbon intensity of its steel and aluminum industries. Canada and Mexico also collectively account for 90% of US steel exports and 84% of US aluminum exports. Therefore, this CBAM scenario is unlikely to trigger retaliatory actions that meaningfully disrupt these US industries.14 With regard to WTO compliance, the EU recently approved plans to implement a CBAM later in 2023, providing a broad template the US could use to establish its own policy, provided that imports and domestically-produced goods are subject to the same rules.

Absent Congressional action to limit carbon-intensive imports, the Biden Administration has been coordinating with EU policymakers to enact a Global Arrangement on Sustainable Steel and Aluminum based on its authority to address national security concerns via trade policy.15 While this represents an important first step in closing the carbon loophole, it could invite WTO scrutiny and cause other trading partners to enact retaliatory trade policies that affect unrelated US industries. Conversely, it may attract other countries to join the agreement, initiating a climate trade alliance that incentivizes broader adoption of clean manufacturing practices. For the moment, this potential trade arrangement is limited to steel and aluminum. But Congress can build on the Administration’s work to design a CBAM that expands the list of covered materials and addresses potential concerns.

Alternative Scenarios

In addition to its recommended framework,16 GEI also considered alternative CBAM frameworks to measure the economic and climate impact of different policy designs. One alternative distinguishes between primary and secondary steel and aluminum in setting carbon intensity thresholds rather than using the weighted average intensity as in the recommended framework.17 In previous reports, Third Way has advocated for disaggregating primary and secondary steel as different products given the inherent embodied carbon advantage of secondary steel production. As noted in our report Clean Steel: Policies to Help America Lead:

While secondary steel made from melting scrap in an electric arc furnace facility is less carbon intensive than primary steel made from converting iron ore to steel in a blast furnace facility, they are not direct substitutes. Large buyers in the building and automotive industries, for example, require higher-quality primary steel to meet regulatory requirements for their products.

GEI found that both the emissions savings and revenue potential of a CBAM diminish significantly under the scenario that classifies primary and secondary steel and aluminum separately.18 Therefore, it will take nuanced policymaking to maximize the benefits of a CBAM while supporting the primary steel and aluminum making facilities in the US. Considering that this policy ultimately raises more revenue than it levies on US facilities, that money can be redirected for the development of low-carbon production using clean hydrogen direct reduced iron (DRI) or carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies, and primary steel and aluminum making facilities should be prioritized in order to bring them closer to embodied carbon parity with secondary facilities.

Another alternative framework GEI explores is using economy-wide carbon intensity for the evaluation of goods manufactured in developing countries with limited or questionable data reporting.19 While intended to incentivize greater transparency and punish inadequate or misleading carbon intensity disclosures, this approach proves ineffective at addressing those concerns, and in some cases, provides high-embodied carbon imports with unintended favorable treatment. For instance, manufacturers in countries such as India, China, and United Arab Emirates (UAE) would pay a smaller adjustment fee on their aluminum exports to the US than they would under a framework that considers average aluminum industry intensity by country, based on available data. Consequently, this scenario results in fewer emissions savings and less revenue while effectively rewarding high-polluting manufacturers. This obviously runs counter to the goal of a CBAM but does highlight the need for a standardized way to measure and disclose product embodied carbon. Luckily, there are useful tools that can help address this gap and policy developments underway to scale their use.

Complementary Policies

The disclosure and collection of sound data on product embodied carbon is foundational to a fair, effective CBAM framework. In order to realize the climate and economic benefits of this trade policy, the US needs robust, verified data to know how to set product standards and assess fees.

Environmental product declarations (EPDs) have emerged in recent years as the answer to this question of embodied carbon disclosure. An EPD is a third-party verified report that conveys the embodied carbon of a product, based on an underlying lifecycle assessment, and has allowed manufactures of common construction materials to report standardized data to inform sustainable building practices. Both public and private buyers, including the federal government, use EPDs to compare products and make more climate-friendly procurement decisions. And they’re about to become even more popular.

The IRA included over $5 billion in funding to drive increased demand for low-carbon construction materials, like steel and aluminum, including over $4 billion for cleaner procurement and $350 million for enhanced embodied carbon data transparency. These low-carbon procurement programs, as well as the Biden Administration’s broader Buy Clean procurement efforts, incentivize federal contractors to use low-carbon materials in certain federal and state infrastructure projects, as measured by EPDs. At the same time, states have also begun implementing their own Buy Clean procurement programs that require the submission of EPDs. Given these trends, manufacturers of all major construction materials will soon need to calculate and disclose the embodied carbon of their products via EPDs in order to compete for government infrastructure dollars.

Recognizing the need to scale the use of EPDs to implement effective low-carbon procurement programs, Congress provided $250 million to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to administer technical and financial assistance to manufacturers seeking to calculate and disclose the embodied carbon of their products. The EPD Assistance Program will provide the necessary resources to ensure EPDs are widely adopted. Congress also provided $100 million to EPA to develop a low-carbon labeling system to streamline product comparison.

Congress can leverage these resources to implement a CBAM framework that evaluates products based on EPD submissions. This would alleviate reliability concerns, because EPDs are third-party verified, and allow for product-specific evaluations that are more accurate than evaluations based on average carbon intensities of the wider company or even country. Furthermore, it supports Buy Clean procurement efforts by helping to proliferate the use of EPDs, driving further demand for low-carbon products.

US manufacturers are uniquely positioned to meet this demand by leveraging the suite of industrial decarbonization programs included in recently enacted laws. For instance, the IRA and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) provided Department of Energy has $6.3 billion to develop and deploy advanced industrial technologies to lower the carbon intensity of commonly-used materials like iron, steel, aluminum, cement, glass, paper, and chemicals.20 The IRA also enacted a number of tax provisions to lower the US’s industrial carbon footprint, including credits for cutting more than 20% of baseline emissions at manufacturing facilities (48C), installing CCUS technologies (45Q), and developing clean hydrogen (45V), which can be used to manufacture cleaner goods. These policies reflect the Biden Administration’s commitment to revitalizing a stronger, cleaner industrial base in the US, helping domestic manufacturers maintain their carbon advantage and capitalize on potential trade policies that incorporate the cost of embodied carbon.