Memo Published January 29, 2021 · 23 minute read

Unpacking US Cyber Sanctions

Allison Peters & Pierce MacConaghy

Takeaways

One of the authors of this brief, Allison Peters, has since departed Third Way. This brief was written and finalized prior to her departure.

Malicious cyber activity poses one of the greatest threats to America’s national, economic, and personal security. Yet, the perpetrators of these crimes largely operate with pure impunity and face little consequences for their actions. This is particularly the case for cybercriminals who cost the US economy anywhere from $57 billion to $109 billion in 2016 alone.1

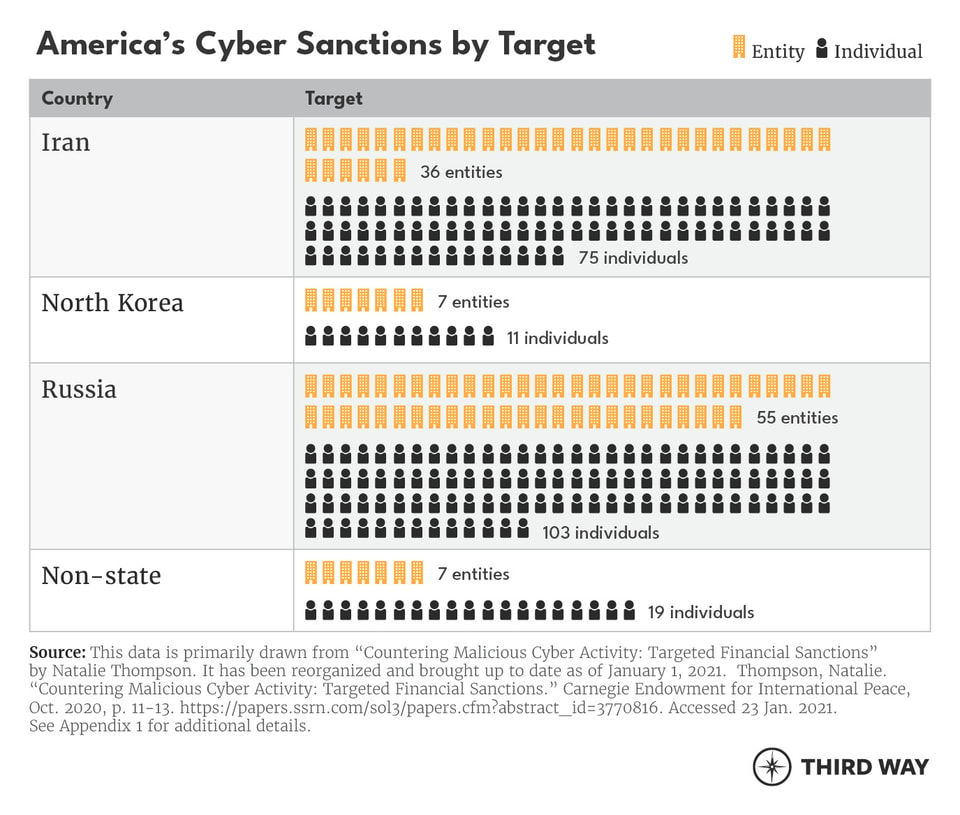

Since 2015, the United States has imposed targeted sanctions (e.g., asset freezes, travel bans) on over 300 individuals and entities in response to malicious cyber activity.2 Many of these sanctions were issued under the cyber-related sanctions program administered by the Department of Treasury and established by a series of Executive Orders under Presidents Obama and Trump and bills passed by Congress.3 Sanctions have largely been imposed on individuals with ties to Iran, Russia, and North Korea, and, in about half of these cases, sanctions have followed indictments. An overwhelming majority of these sanctions have targeted individuals with suspected links to government entities and, only recently, have cyber sanctions targeted cybercriminals.4

As targeted sanctions increasingly become a tool deployed by the US government to punish malicious cyber actors, it remains unclear whether they are having an impact in changing behavior. Research on the impact of sanctions more broadly indicates that sanctions can be an effective tool to impose consequences on bad actors and change their actions when employed multilaterally, as part of a coherent strategy, and effectively messaged.5 However, imposing sanctions on malicious cyber actors without continuously reassessing their impact and the expected reciprocal actions by the target(s), risks a number of potentially negative outcomes.

While Congress introduced legislation in the 116th Congress to impose new or codify existing cyber-related sanctions into law,6 it has not exercised the necessary oversight over the Executive Branch’s strategy in issuing cyber-related sanctions and determining their efficacy.

With other countries now following America’s lead in issuing these sanctions, the time is ripe for the new Congress to push for an inter-agency, holistic assessment of the impact of US cyber-related sanctions.7 And with cybercrime increasingly threatening all sectors of the US economy, Congress must call for an evaluation as to whether sanctions on non-state cybercriminals should increasingly be used.

This memo includes an explainer of cyber sanctions and recommendations for Congress to conduct more oversight in four sections:

- A brief analysis of the nature of cyber activity committed against the United States;

- An overview of the history of US cyber sanctions and an analysis of the actors they have targeted;

- An assessment of existing research on sanctions as a tool of US foreign policy and the implications of this research on cyber-related sanctions; and

- Recommendations for Congress to assess the impact of cyber-related sanctions and conduct proper oversight over the issuance of these sanctions.

Malicious cyber activity poses a direct threat to America’s national, economic, and human security, and sanctions have been deployed by the US government to impose consequences on the perpetrators.

Malicious cyber activity is surging in the United States, targeting its people, undermining its national security, and affecting nearly every sector of its economy. Nearly one in four American households have fallen victim to a cybercrime.8 Entire state and local governments have been held hostage by ransomware (a form of cybercrime), resulting in millions of dollars lost in recovery costs.9 And now, America’s hospitals and schools are being targeted in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.10 Foreign adversaries have also leveraged cybercrime tools and employed cybercriminals to steal America’s national security secrets and intellectual property.11

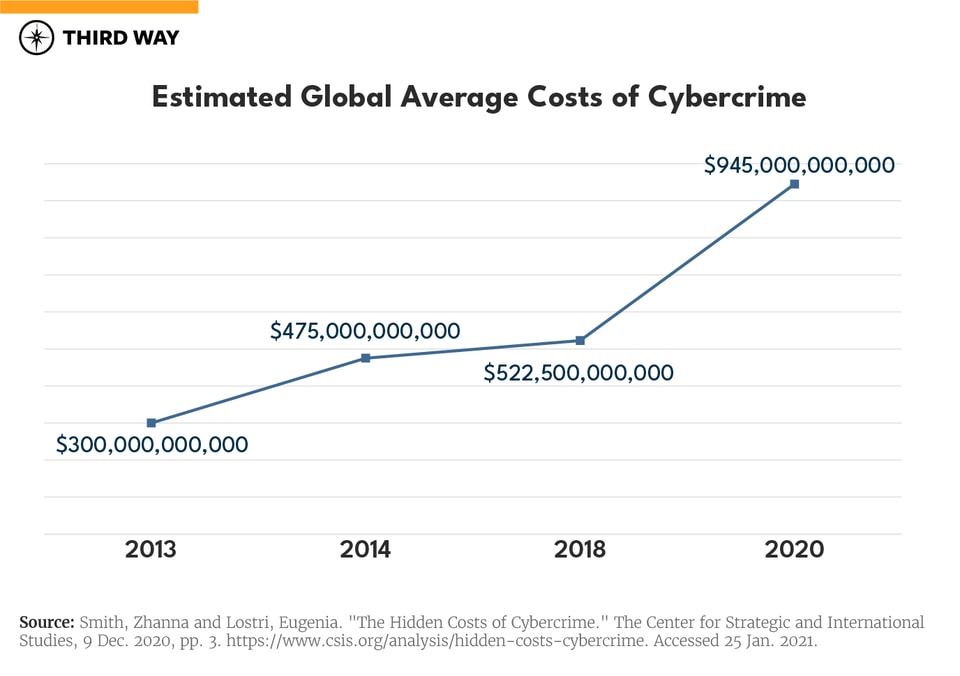

The economic losses resulting from cybercrime in the United States and globally are staggering. In 2016 alone, cybercriminals cost the US economy anywhere from $57 billion to $109 billion, according to the last White House Council on Economic Advisors assessment.12 Each year, the global impact also grows. In December 2020, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) reported the cost of cybercrime reached over $1 trillion globally, which was a 50% increase from their 2018 assessment.13In particular, the economic losses from ransomware have continued to surge during the COVID-19 pandemic. One recent report found a 311% increase in 2020 from 2019 in cryptocurrency received by criminal addresses from ransomware for a total of just under $350 million.14

The perpetrators of malicious cyber activity range from state-sponsored or -enabled actors, organized criminal groups, and lone actors. One study found non-state cybercriminals conducted 57% of the largest cyber loss events in the world between 2015 and 2019. The other 43% of these attacks were perpetrated by state-sponsored or -enabled actors.15 Some US assessments indicate cybercriminals are generally more motivated by financial reasons, while nation-state actors tend to be more focused on stealing, destroying, or compromising victim data.16The line between nation-state actors and non-state cybercriminals, however, has blurred as states abet and directly employ non-state cybercriminals and/or their tools.17

Despite the proliferation of a wide spectrum of cyber activity against the United States, the state and non-state actors committing it rarely face consequences. But sanctions have emerged as a tool increasingly used to deter and/or compel a change in their behavior. Yet compared to the number of incidents, few actors who engage in malicious cyber activity are sanctioned. Of those that are, they are largely nation-state-connected actors residing in countries that are particularly difficult for US authorities to reach.

The number of sanctions for malicious cyber activity remains comparatively low to the overall number of sanctions issued and questions remain about their effectiveness.

As the number of malicious cyber incidents in the United States has grown, so too has the number of cyber sanctions.18 US policymakers have used economic pressure to advance foreign policy goals and respond to threats against the nation since the dawn of the Republic, and sanctions have now increasingly, albeit sparingly, become a tool of response to malicious cyber activity. In 2015, then-President Barack Obama issued the first executive order (EO) to institute a sanctions regime targeting the individuals and entities behind “significant cyber-enabled activities.”19 These cyber sanctions along with sanctions programs established to deal with particular countries and security threats of concern, including terrorism, have been used to target the individuals and entities behind cyberattacks and other cyber activity against the United States.

The US government imposes sanctions broadly to alter the strategic decisions of state and non-state actors that threaten US interests or in response to particularly egregious behavior. A form of sanctions was first established in 1807 when Congress passed the “Embargo Act.”20 Over two centuries later, the globalization of economic markets and the desire for new tools to combat threats to national and global security has contributed to substantial innovation in the use of coercive economic measures such as sanctions. Sanctions programs have continued to grow in size and scope. They can either be comprehensive (i.e., restrictions on trade and commercial activity with an entire country) or targeted (i.e., restrictions on the activity of specific individuals and/or entities). Many federal government entities play a role in administering sanctions and tracking their implementation, including the Departments of Treasury (namely through its Office of Foreign Assets Control or OFAC), State, and Commerce.21 The Government Accountability Office (GAO) highlights that:

“Sanctions may place restrictions on a country’s entire economy, targeted sectors of the economy, or individuals or corporate entities. Reasons for sanctions range widely, including support for terrorism, narcotics trafficking, weapons proliferation, and human rights abuses. Economic restrictions can include, for example, denying a designated entity access to the U.S. financial system, freezing an entity’s assets under U.S. jurisdiction, or prohibiting the export of restricted items.”22

As of December 2020, the United States has nearly 8,000 sanctions in place on individuals, companies, or entire countries.23 Of those 8,000, a little more than 300 are for malicious cyber activity.24

Debate continues as to the effectiveness of sanctions overall and their impact. Critics argue that sanctions are poorly designed and rarely successful in changing a target’s conduct.25 And there is growing recognition that comprehensive sanctions on entire countries have contributed to a number of humanitarian crises and corruption.26 However, others have argued that sanctions have become more effective in recent years as they have become more targeted in nature.27 And some research has given sanctions credit, at least in part, for changing the behavior of governments in Libya and South Africa in the past.28

Broadly, the authorities for US sanctions programs may originate through executive or legislative action. Pursuant to the “International Emergency Economic Powers Act” (IEEPA, P.L. 95-223), the President, upon declaring a state of emergency, can institute sanctions by EO against countries or individuals in response to an “unusual and extraordinary” threat.29 Congress, for its part, may also pass legislation imposing new sanctions or modifying existing ones.

Against this backdrop, the US government first started sanctioning actors accused of committing malicious cyber-enabled activity in 2012 under a number of different authorities.30 Subsequently, in 2015, then-President Obama issued EO 13694,31 later amended in 2016 to include election interference in EO 13757,32 establishing a dedicated sanctions program to respond to significant malicious cyber-enabled activities with asset freezes, travel restrictions, and property and interest blocks. Lawmakers codified portions of these EOs in 2017 with the passage of the “Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act” (CAATSA, P.L. 115-44), which provides for sanctions against individuals or entities that engage in “significant activities undermining cybersecurity” on behalf of Russia.33 Further, in 2018, then-President Trump also issued EO 13848, imposing sanctions for election interference.34 These EOs and CAATSA covered several categories of activity, including foreign election interference, infiltration and/or disruption of computer networks, and misappropriation of trade secrets stolen via cyber-enabled means.35

Using these and other authorities, the US government has instituted targeted sanctions on a number of individuals and entities for their malicious cyber activity. According to research by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and with more recent additions added since that research was finalized, the United States had imposed sanctions 35 times, targeting over 300 people and entities, in response to malicious cyber activity under several different authorities, including the cyber-related sanctions program.36 (See Appendix 1) The sanctioned activity has ranged from cyber-enabled espionage, election interference, design and distribution of destructive malware, exchanging currency gained from ransomware attacks, business email compromise, and other cyber activity.37 Preceding or simultaneous to the issuance of these sanctions, the Department of Justice has also indicted about half of these same individuals and entities, indicating that indictments can serve as an important tool allowing the US federal government to lay out the case against these actors for follow-up action such as sanctions.

The US government has predominantly deployed cyber sanctions against nation-state-connected individuals or entities in three countries: Iran, North Korea, and Russia.38 Cyber sanctions have also been issued against individuals in other countries in a few select cases.39 Some organizations have criticized the United States for failing to sanction Chinese cyber actors despite the tremendous amount of malicious cyber activity emanating from China.40 As of December 2020, some entities with business in China have been sanctioned but for facilitating individuals’ evasion of US cyber sanctions.41Additionally, while the Department of Justice has indicted several Chinese citizens for malicious cyber activity,42 only two with no suspected ties to the Chinese government have been the target of sanctions for conducting malicious cyber activity.43 In response to malicious cyber activity emanating from China, the US government has largely pursued other actions, including diplomatic negotiations.44

Despite some estimates indicating non-state actors, mainly cybercriminals, accounted for over 50% of the largest cyber loss events in the world between 2015 and 2019,45 only 26 suspected non-state individuals or entities were sanctioned for cyber activity as of December 2020. (Though the increased blurring of the boundary between state and non-state actors, as states abetted and in some instances directly employed non-state cybercriminals and/or their tools to advance their objectives, makes such clear delineation difficult and should be kept in mind.)46 Research has shown that while sanctions on non-state actors may not change their calculus, they can have an impact on freezing these illicit actors out of legitimate financial systems in order to deny them resources.47 Sanctions can make it “costlier, riskier, [and] less efficient” for non-state actors to use and move funds.48 And they may also protect the integrity of the financial system.49

Overall, there is little to no publicly available information to indicate whether these cyber sanctions are or are not having an impact in achieving their goals. The objectives of sanctions go beyond just punishing a malicious actor and include disrupting the financing and recruiting efforts of would-be hackers and changing the long-term behavior of actors in cyberspace.50 There are no publicly available assessments to indicate whether these sanctions are meeting these objectives. Further, the 2018 National Cyber Strategy makes little mention of how economic sanctions fit into the US government’s broader strategic approach to dealing with malicious cyber actors.51 This Strategy also did not establish a framework as to how decisions are being made and which actors US cyber sanctions will target, leading to concerns over inconsistent applications.52 In a March 2020 hearing before a House Appropriations subcommittee, then-Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin did not directly answer a question as to whether cyber sanctions have been effective. Mnuchin responded, “I do think our sanctions programs work, and I do think we’re sanctioning the right people, and I do believe we have proper resources.”53

Five years after President Obama issued his first EO to establish an American cyber-related sanctions program, other countries are now following suit. Both the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK) have adopted cyber sanctions regimes closely mirroring that of the United States, though there are some noted differences.54 In July 2020, the EU imposed cyber sanctions for the first time on six individuals and three entities from North Korea, Russia, and China, who are suspected to be responsible for a number of different cyberattacks and cyber espionage.55 In October 2020, the Group of Seven (G7), a forum of the world’s seven leading industrial nations, stated it would explore opportunities to impose more coordinated, targeted financial sanctions in response to malicious cyber activity.56

As the US government works to advocate for other countries to establish cyber sanctions regimes and coordinates multilaterally to impose sanctions, it is critical that it can demonstrate the impact of these efforts. Research on sanctions broadly can offer some important insights.

It remains unclear whether cyber sanctions are having an impact in changing target behavior but research on sanctions broadly can offer some key insights.

Research on sanctions broadly as a US foreign policy tool indicates that these measures can have an impact when certain conditions are met. As the relevant federal entities work to determine whether sanctions should increasingly be used against malicious cyber actors, including non-state cybercriminals, this research can help guide a strategic approach for how to proceed.

The US government is using sanctions more than ever before.57 According to the GAO, there are now 20 country-based sanctions programs. Additional programs target individuals or entities regardless of their geographic location for their involvement in security threats like terrorism, narcotics trafficking, and malicious cyber activity.58 Even as more sanctions are imposed, and foreign governments adopt their own measures, however, assessing the effectiveness of these actions remains a difficult process. GAO found that may be, in part, because US government entities are not required to determine whether sanctions “work.”59In October 2019, GAO reported that the Departments of Treasury, State, and Commerce conduct assessments on sanctions’ impact on specific targets, but not their overall effectiveness in meeting US policy goals.60

Sanctions research sheds light on when these measures overall can be most effective. The US Cyberspace Solarium Commission rightfully highlighted in its final report that the “efficacy of sanctions depends heavily on a number of factors, including their target and timeline, the degree of international coordination, and the path to lifting them.”61 Some research has suggested that economic sanctions have resulted in some meaningful change in the sanctioned country about 40% of the time.62 However, scholars debate whether there is an actual causal relationship between sanctions and these behavioral changes in a number of cases. For example, some see South Africa’s repeal of the legal framework for apartheid as a direct result of sanctions. Others maintain it was unrelated.63 Libya’s decision to abandon its weapons of mass destruction programs and support for terrorism in 2003 has been held as a model for an effective sanctions regime, but others question whether other issues and actions had a greater influence on this decision.64

Against state actors, sanctions have proved effective when implemented multilaterally, effectively messaged, and as part of a coherent strategy. GAO found that sanctions were successful in changing behavior when they were implemented in concert with other countries and “when targeted countries had some existing dependency on or relationship with the United States,” such as foreign aid or military support.65 GAO also found “strong evidence that the economic impact of sanctions has generally been greater when they were more comprehensive in scope or severity.”66 But there is also evidence to suggest that when sanctions are effectively messaged (i.e., when the sanctioned state understands what behavior the sanctions are targeting and what behavior is necessary to achieve a lifting in sanctions) sanctioned states are more likely to change their behavior.67

Research on sanctions against non-state actors has focused primarily on their impact on terrorism.68 The studies find that sanctions are not particularly effective at changing terrorists’ ideology but can effectively disrupt their access to financial markets, thereby limiting their ability to conduct attacks.69 The application of national and international sanctions, coupled with close cooperation with foreign partners and the private sector, and enhancements in international financial transparency have made it harder for “terrorist groups to raise, move, store, and use funds.”70 In particular, al-Qaeda’s financial network has been undermined through the use of targeted financial measures, sustained engagement in key areas, and the development of innovative systems by which to collect financial intelligence.”71 In the post-9/11 period, scholars have noted the success of the international community in “significantly hobbling terrorist groups by restricting access to legitimate financial channels.”72 Disrupting these sources has been a core component of the fight to destroy terrorist groups73 and could be similarly successful against transnational criminal organizations that rely on cybercrime for resources.

Lessons learned from this research indicate that coordinating cyber sanctions with foreign partners and the private sector and quickly identifying and seizing financial assets is essential when dealing with non-state cybercriminals. Cybercriminals with no ties to nation-states may have fewer links to the global financial system, which may mean targeted sanctions could be effective against these actors though they have been rarely used against them.74 This research also suggests effectively messaging what behavior the sanctions are targeting and what can be done by the targeted actor to reduce those sanctions may deter future cybercrime.75

However, the imposition of sanctions can have drawbacks. First, over time, international compliance with sanctions can diminish, particularly when the sanctioned activity has passed.76 Second, too many sanctions may limit the potency of sanctions in the future. Banks are subject to liability if they maintain accounts for illicit actors, even if they did not willfully violate sanctions regimes.77 To avoid incurring stiff penalties, they will often not open accounts with respect to certain activities. 78 Additionally, legitimate entities and people may seek out alternative financial systems to avoid liability concerns, driving them away from the US financial system. This may include the increased use of cryptocurrency.79 Paradoxically, this limits the reach of US sanctioning power by driving illicit activity to unregulated areas and pushing higher-risk clients to banks that may have fewer resources to detect illegal transactions.80 Finally, the overuse of sanctions may impugn the power of sanctions as a tool to advance US goals in the future if they do not result in the intended effect.81 A continual reassessment of how cyber sanctions fit into a broader strategic approach toward dealing with their targets and their impact is vital to mitigate these risks.

Nonetheless, sanctions can be a useful tool to impact a target’s behavior and impose consequences on those that may be out of reach for US law enforcement authorities. The US Cyberspace Solarium Commission found the use of sanctions as part of a layered deterrence strategy “will not eliminate state-sponsored cyber operations or cybercrime, but consistently enforced consequences and rewards can begin to erode the incentives for bad behavior.”82 Sanctions can also have other critical impacts such as cutting off financial flows, galvanizing global support for further actions against malicious cyber actors, and enforcing norms of responsible behavior in cyberspace. They may also serve an important signaling function by allowing the US government to detail the malicious cyber activity it is targeting in the public domain. This could, for example, signal to cybersecurity practitioners those actors they should be particularly focused on.83 Moving forward, Congress must now exercise its oversight role over US cyber-related sanctions to assess their impact.

Congress has not exercised the necessary oversight over the Executive Branch’s strategy to issue cyber-related sanctions and determine their efficacy.

Congress can play a key role in maintaining oversight of US cyber sanctions. As the 117th Congress and a new presidential administration begins, Members should prioritize pushing for assessments on the efficacy of existing sanctions and recommendations to ensure such sanctions are being issued in a strategic and coordinated manner across the US government. There are a number of actions Members can take to put this into action.

First, as Members of Congress conduct relevant hearings, the following questions are important for them to raise about cyber sanctions:

- What is the Administration’s view of how cyber sanctions fit into their overall strategic approach to dealing with malicious cyber threats?

- What role can these sanctions play in imposing consequences on cybercriminals, and should the US government increase the use of sanctions on these criminals? What impact might that have?

- Are the goals of the cyber sanctions issued so far clearly defined inside the US government?

- How are decisions being made as to when sanctions are issued against individuals and entities in different countries? What factors does the Administration consider when making those decisions?

- What are the criteria that will be used to determine whether any existing cyber sanctions should be lifted?

- How are intelligence assessments used in the process of issuing and reviewing the effectiveness of sanctions? How do these assessments factor into determinations of what any expected reciprocal actions might be and eventually whether they are having the intended impact?

- Is there a clear communication strategy about the precise behavior that cyber sanctions are targeting so the targets themselves understand what is being sought?

- How are cyber sanctions being coupled with other actions, including other forms of economic pressure, in order to develop a comprehensive and cohesive strategy toward the nation-states and/or organizations being targeted?

- What risks and rewards does the Executive Branch weigh in determining whether further sanctions on entities for malicious cyber activity are needed?

- What is the Administration’s strategy to expanding a more multilateral approach to the issuance of cyber sanctions? What have been the impediments to doing so?

- Do the Departments of Treasury, State, and Commerce have the adequate resources to meet the needs of the cyber-related sanctions programs and ensure these sanctions are being properly monitored and evaluated?

Second, Congress can push the Executive Branch to assess the impact of its approach to cyber-related sanctions to ensure they are issued strategically and consistently. To do so, Congress can require the Department of Treasury, in coordination with all relevant federal entities, including the Intelligence Community, to undertake an inter-agency assessment of the effectiveness of all existing cyber-related sanctions in halting or reducing malicious cyber activity. It has been over five years since President Obama issued the first Executive Order to establish a dedicated cyber sanctions regime in the United States. The time is ripe for an inter-agency, holistic assessment of the impact of such cyber-related sanctions. This assessment can be institutionalized every four years, in conjunction with the update of the State Department’s global cyber engagement strategy and the White House’s national cyber strategy. Recommendations on the specific components of this assessment can be found in Third Way’s “Roadmap to Strengthen US Cyber Enforcement.”84

Finally, Congress should provide support to the Departments of State and Treasury to boost resources to non-governmental research institutions that can conduct regular, independent assessments of the effectiveness of cyber sanctions and propose recommendations to improve the US’s cyber sanctions regime. As cyber sanctions have increasingly become a tool in America’s cyber diplomacy toolbox, agencies should invest resources in organizations outside of the government to study whether these sanctions are working and what impact they might be having on the US financial system.

Conclusion

In recent years, sanctions have emerged as a frequent tool of American foreign policy. Since the cyber-related sanctions program was formally established, these sanctions have increasingly, albeit sparingly, been used as a tool to impose consequences on malicious cyber actors. Yet, there is little publicly available data to assess whether these cyber sanctions have had an impact in changing their target(s) behavior or achieving other established goals. Research on sanctions broadly offers some guidance on how cyber sanctions can prove effective. Accounting for these insights, Congress should exercise its oversight function and raise a number of questions about the strategy and impact of cyber sanctions during budget and nomination hearings and meetings with the Executive Branch. This should include raising the question as to whether sanctions should be used more to target cybercriminals. Finally, Congress should push for a formal assessment on the impact of the US government’s cyber sanctions program and provide support for organizations to conduct independent research into these questions.

Appendix 1

The following chart documents the sanctions that have been issued by the US government for malicious cyber activity under a number of authorities, including but not limited to the cyber-enabled sanctions program. It lists the country or non-state actor linked to the malicious cyber activity (though it should be noted that those listed as non-state actors may have some linkages to state entities), the number of individuals or entities sanctioned, the authority under which the sanctions were issued, and the date of issuance.85

|

Country |

Target |

Authority |

Date |

|

Iran |

1 entity |

Terrorism (EO 13224) |

|

|

Iran |

1 individual; 6 entities |

Human Rights (EO 13606) |

|

|

Iran |

3 individuals; 6 entities |

Iran (EO 13628) |

|

|

Iran |

1 individual; 4 entities |

Iran Threat Reduction and Syrian Human Rights Act (P.L. 112-158) |

|

|

Iran |

2 entities |

Iran (EO 13628) |

|

|

Iran |

2 entities |

Iran (EO 13628), Human Rights (EO 13553) |

|

|

Iran |

7 individuals; 1 entity |

Cyber (EO 13694) |

|

|

Iran |

3 entities |

Iran (EO 13606, 13628) |

|

|

Iran |

10 individuals; 1 entity |

Cyber (EO 13694) |

|

|

Iran |

2 individuals; 1 entity |

Iran (EO 13606, 13628) |

|

|

Iran |

6 individuals; 1 entity |

Iran (EO 13606) |

|

|

Iran |

1 entity |

Weapons of Mass Destruction (EO 13382) |

|

|

Iran |

45 individuals; 2 entities |

Human Rights (EO 13553, 13572), Terrorism (EO 13224) |

|

|

Iran |

5 entities |

Election Interference (EO 13848) |

|

|

North Korea |

10 individuals; 3 entities |

North Korea (EO 13687) |

|

|

North Korea |

1 individual; 1 entity |

North Korea (EO 13722) |

|

|

North Korea |

3 entities |

North Korea (EO 13722) |

|

|

Russia |

4 individuals; 5 entities |

Cyber (EO 13757) |

|

|

Russia |

19 individuals; 5 entities |

Cyber (EO 13694), CAATSA |

|

|

Russia |

24 individuals, 14 entities |

Ukraine (EO 13661, 13662), Syria (EO 13582), CAATSA |

|

|

Russia |

3 individuals; 5 entities |

Cyber (EO 13694), CAATSA |

|

|

Russia |

2 individuals; 2 entities |

Cyber (EO 13694), CAATSA |

|

|

Russia |

15 individuals; 4 entities |

Cyber (EO 13694), CAATSA |

|

|

Russia |

7 individuals; 8 entities |

Election Interference (EO 13848) |

|

|

Russia |

17 individuals; 4 entities |

Cyber (EO 13694), CAATSA |

|

|

Russia |

4 individuals |

Cyber (EO 13694), Election Interference (EO 13848) |

|

|

Russia |

8 individuals; 7 entities |

Election Interference (EO 13848), Cyber (EO 13694), Ukraine (EO 13661) |

|

|

Russia |

1 entity |

CAATSA |

|

|

Non-state |

2 individuals |

Cyber (EO 13694) |

|

|

Non-state |

2 individuals; 2 entities |

Transnational Criminal Organizations (EO 13581) |

|

|

Non-state |

2 individuals |

Cyber (EO 13694) |

|

|

Non-state |

2 individuals |

Cyber (EO 13694) |

|

|

Non-state |

6 individuals |

Cyber (EO 13694) |

|

|

Non-state |

3 individuals, 5 entities |

Cyber (EO 13694) |

|

|

Non-state |

2 individuals |

Cyber (EO 13694, 13757) |