Memo Published October 15, 2020 · 14 minute read

Voters Trust Science (Sort Of)

Jackie Toth & Jared DeWese

“We have watched for 40 years as, unfortunately, we have seen groups that have done their best to not simply tell us things that are untrue, but to weaken our faith in science, to weaken our faith in facts. We have watched from the highest levels of government this very false equivalence between propaganda and truth.”

Former Georgia House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams at Third Way’s Fastest Path to Zero Summit

Key Takeaways

Amid the worst pandemic to impact Americans in over a century, more than half of US voters in several battleground states are reporting changes in the level of trust they place in scientists and public health experts, according to public opinion research Third Way conducted this summer with ALG Research. While nearly a third of these voters have greater confidence in scientists since the start of the pandemic, 22% say their trust in scientists has weakened. Whether these changes in trust will endure is unclear, but voters’ confidence in science—and their sense of elected officials’ approach to it—has important implications for communicating scientific issues, from public health to climate change.

From this research, it’s evident that large majorities of these voters generally want policymakers to listen to experts and to admit what they don’t know; that Democrats and Republicans are split over the role scientists and their findings should play in policymaking; and that voters continue to discount the depth of the scientific consensus on a range of issues.

Introduction

As soon as President Donald Trump entered office in 2017, his administration began taking major steps to invalidate science and the scientific community. From erasing references to climate change on agency websites and falsely recreating the path of a hurricane to discrediting scientific analysis from his own administration, Trump has waged a constant war on science.

The administration’s posture toward science came to the fore in March of 2020, when Americans realized they faced the specter of the new coronavirus and much of the country closed down in an attempt to slow its spread. The population’s health and economic outcomes would depend on whether elected leaders sought and acted on the best available science. Americans, forced to stay at home, weighed a daily barrage of White House press briefings against conflicting remarks by the administration’s own public health officials and scientists.

Third Way, with ALG Research, undertook a two-part research project to examine and explore whether the COVID-19 global health pandemic and its handling had affected American voters’ trust in science, and what it could mean for communication and action on climate change. The research included a three-day online focus group from July 13-15, 2020, among 22 urban/suburban general election voters from nine battleground states, and a subsequent survey of 1,500 likely voters across seven battleground states from July 23-29, 2020, with oversamples of 100 Black Americans and 100 Latinos.

Trust in Scientists Is Up

Overall, US voters in the states that Third Way surveyed are generally quite trusting of scientists. We found that nearly half of voters (45%) trust scientists a great deal to act in the public’s best interests—slightly higher than the 39% of randomly selected US adults who said the same to Pew Research Center in April 2020. This deep level of trust has more than doubled from 21% in 2016. However, like Pew, Third Way found that most of that gain in trust is among Democrats, solidifying evidence that a partisan divide has developed over something as fundamental as science. All political affiliations have more deep trust in generic “scientists” than in experts from particular fields—whether public health scientists (34%) or climate scientists (35%).

Even among Democrats, however, there are differences. Democrats of color are more skeptical of scientists than white Democrats. While 72% of white Democrats said they place a great deal of trust in scientists, just 49% of Black Democrats and 47% of Latino Democrats said the same. This disparity in trust has important implications for the eventual success of a COVID-19 vaccine, as Third Way explained in a supplementary memo on voters’ trust in vaccines.

Democrats and Republicans are also split over the role science should play in the decisions of elected officials. A large majority of Democrats said they thought scientific experts are usually better at making good policy choices on the topics they study than others are, and 84% of Democrats wanted policymakers to listen to scientists more and to follow their advice, compared to 37% of Republicans. A majority of Republicans were more attracted to the idea that when scientists and an elected official’s gut feelings disagree, elected leaders should usually or always follow their gut or common sense (53%); only 13% of Democrats favored gut instinct over following the science.

Many QualBoard participants said they thought science should have more influence on government policy. “This virus is more than politics,” said one Democratic Black female from Michigan aged 60-64. “Politicians should be quiet and listen for once.”

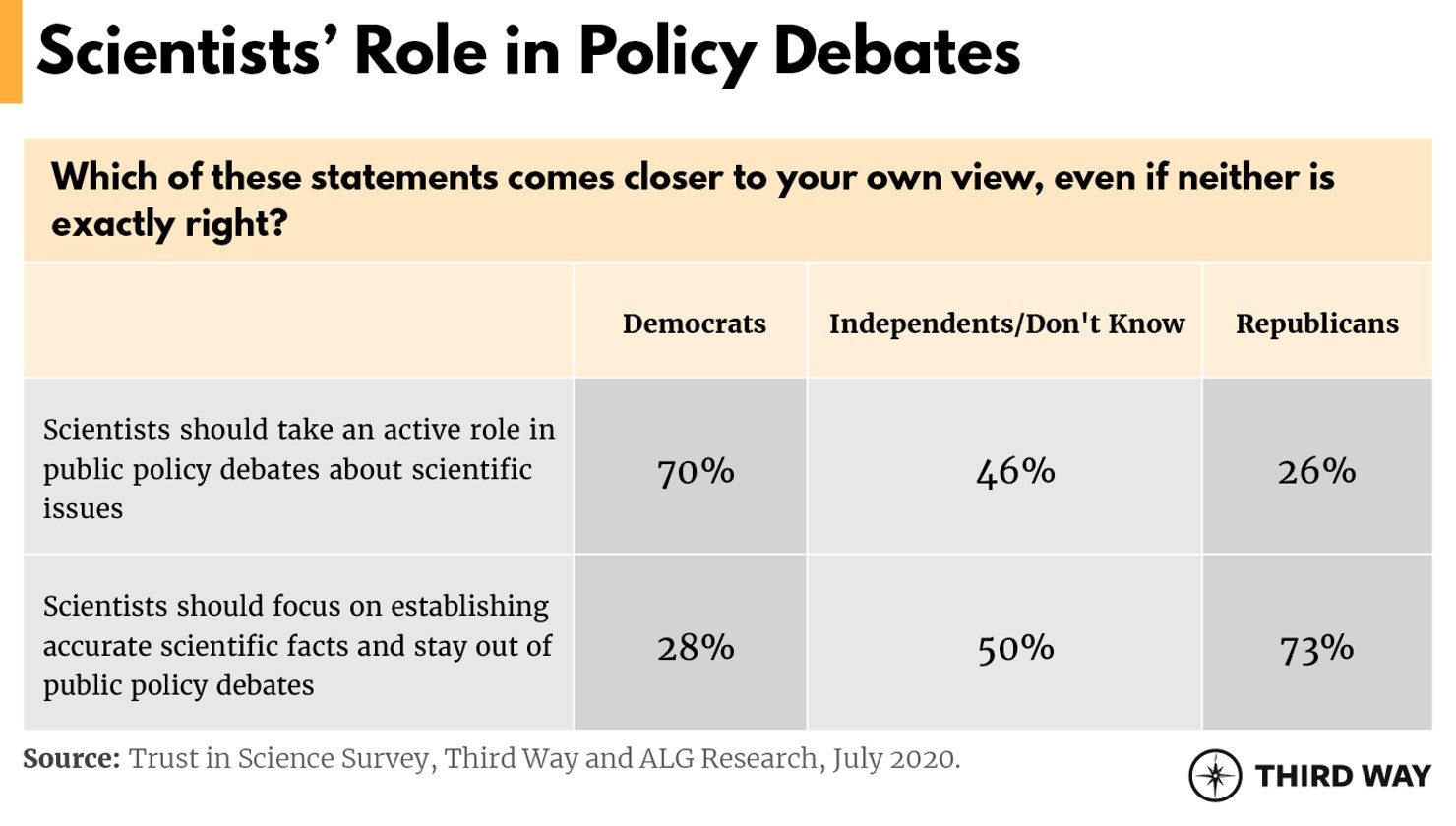

Republicans and Democrats disagreed over whether scientists should take an active role in public policy debates on scientific matters, versus focusing on their work and keeping out of these discussions. The partisan split was consistent with the results of a similar question that Pew has asked US adults.

COVID-19 Impacting Some Voters’ Current Trust in Science

This year, Americans have had to process and weigh conflicting messages about COVID-19. It’s possible that the COVID-19 crisis has altered the extent of adults’ trust in different types of science, but it’s not clear whether these changes are permanent.

While 45% of voters reported having the same amount of confidence in scientists since the start of the pandemic, 31% said they have more confidence, and 22% said they have less. A larger share of Democrats have greater trust in scientists (42%) than do Republicans (23%) or independents (21%). QualBoard participants were similarly mixed in their reported levels of trust compared to six months prior. “I’ve become more confident because not following science has been a disaster,” said a white Democratic Texan male. Others suggested throughout the three day period that the variability of public information they had heard about the transmission, symptoms, and effective safety measures for COVID-19 had weakened their trust in science.

Participants were split over whether scientists’ handling of COVID-19 has increased their trust in the scientific community. An independent Hispanic male aged 50-54 from North Carolina said he “was more naive as to the benevolent nature of science prior to the COVID outbreak. I personally found how the WHO handled the outbreak at the beginning to be unacceptable and I am very happy President Trump cut them off.” Two other participants pushed back on his assertion, though one of them qualified that he thought “some of the so called leadership in the CDC and FDA are soft pedaling some of the science to keep their jobs.”

For a white female Arizonan aged 25-29 who leans Republican, her trust in scientists hasn’t necessarily changed in the last half year. But she added that “we are living in a time where a large number of people are more concerned about what they can gain from a situation, rather than how they can help.”

Comparatively, on climate science, a majority of voters (57%) said they have the same level of trust in climate scientists as they did pre-pandemic, while 23% and 18% say they have more or less trust in climate scientists, respectively. Many focus group participants said they trusted climate scientists because climate change is real or because climate scientists’ conclusions are observable in the real world, though some participants questioned these scientists’ accuracy.

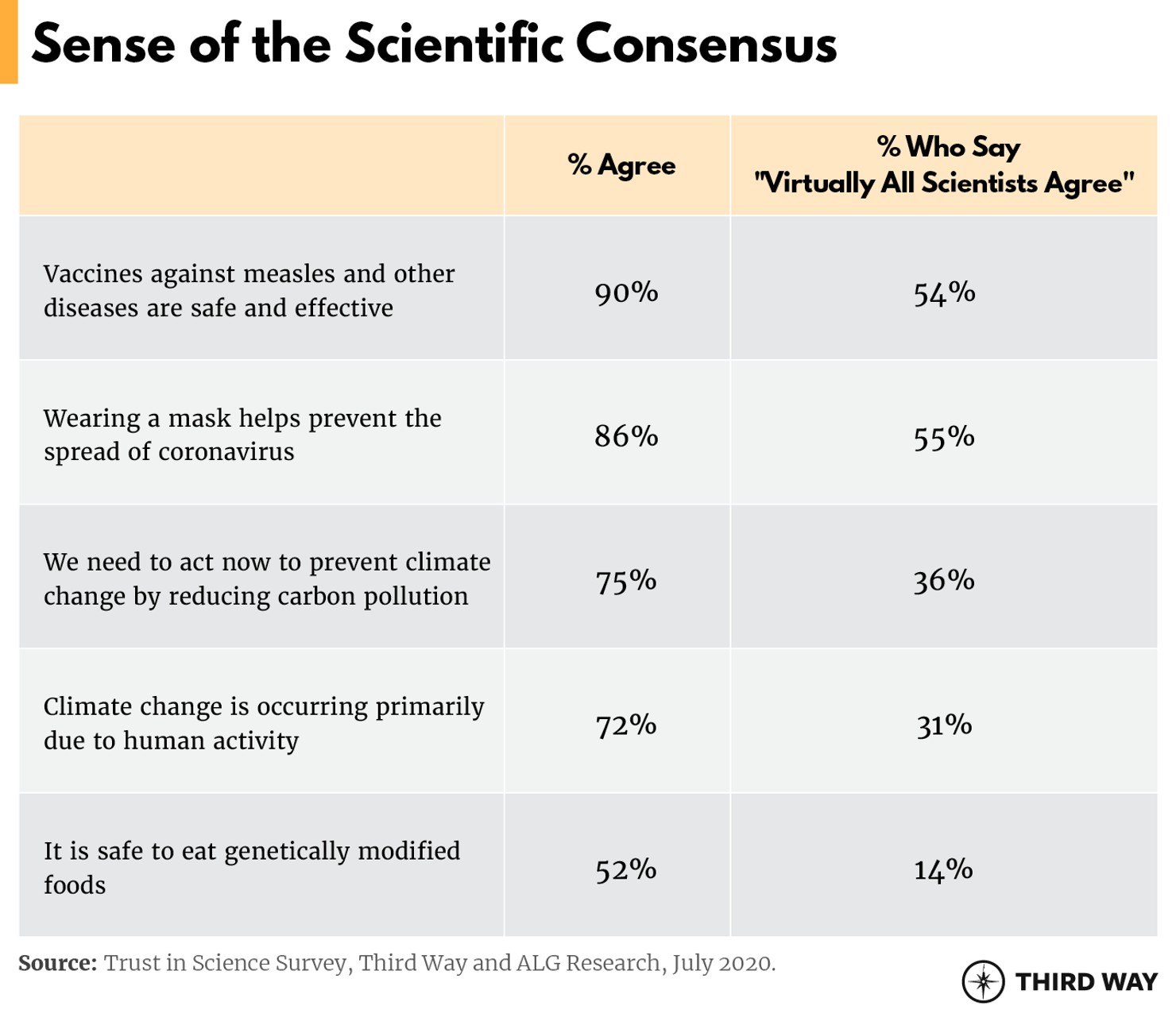

Voters Undercount Scientists’ Consensus

Critically, voters’ personal agreement with facts—from the effectiveness of vaccines and masks to the need for urgent action on climate change—significantly outpaced their sense of the scientific consensus on these issues. While nearly three in four voters (72%) agreed that climate change is primarily human-caused, just 31% of respondents thought that virtually all scientists agree that’s the case. That includes 41% of Democrats, 40% of people under 35, and 35% of college-educated Americans. The gap was similarly vast in voters’ sense of the virtual unanimity among scientists on vaccines, masks’ effectiveness, the causes of climate change, and the safety of genetically-modified foods.

Successful Science Messaging Is Humble, Focused on Expertise

An emphasis on expertise—and a bit of deference to experts—may benefit policymakers and advocates who talk about scientific issues. And while some voters shied away from messaging that drew links or comparisons between COVID-19 to climate change, other groups found these arguments apt.

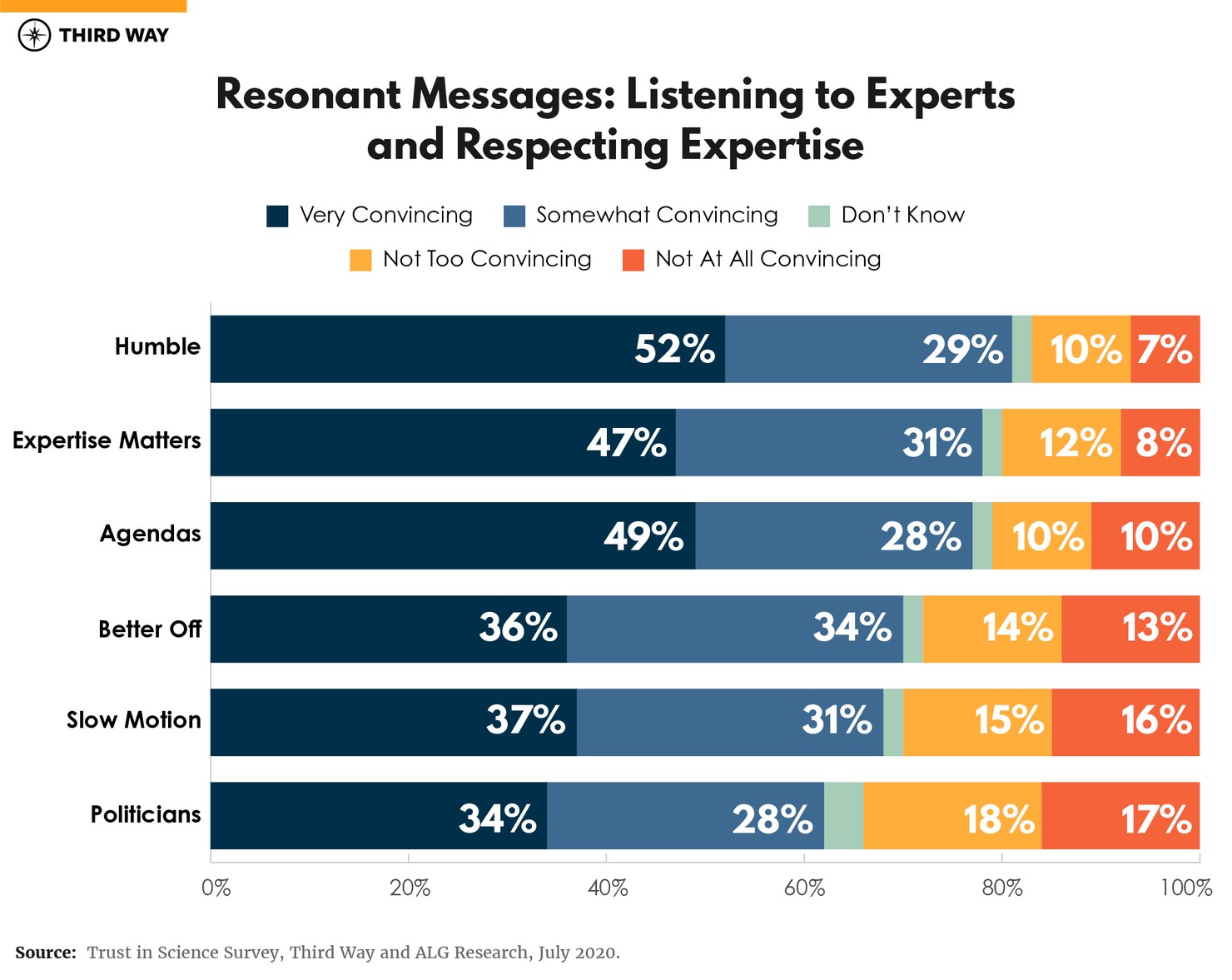

Appeals to humility were the most resonant messages both in the QualBoards and in the poll (see the toplines for full message text). Eighty-one percent of survey respondents found it convincing that the best leaders during COVID-19 have been humble, learning and acting on good advice. It was the message that the largest shares of people of color overall, Democrats, and Republicans, and people of color overall found convincing. “When politicians lead with their ego it's hard for them to admit they don't know,” said a Black female Democrat from Michigan.

Similarly resonant with more than three in four voters (78%) was the idea that expertise matters, and that people should heed those who study one issue their entire life. “They're paid to do their job. I'm paid to do mine. You have to trust the numbers because math is absolute,” shared one white male aged 40-44 in Texas, who identified as an independent closer to the Democratic Party.

Over three in four voters (77%) also responded favorably to a message supposing that those who fight against science have their own agendas to make money or further their political careers.

Comfortable but smaller majorities of voters said they were swayed by messages that made rhetorical connections between COVID-19 and climate change, indicating that drawing such a link may not serve policymakers as well with all audiences. A distinction between the impacts of bold actions to stem COVID-19 causing economic pain versus efforts to address climate change making us better off resonated with 70% of voters. But to an independent Black female participant from Pennsylvania, the statement unduly downplayed the pandemic and suggests that “climate change is THE most pressing issue. Not true when we have people dying by the thousands.”

A message explaining how and why experts have described climate change as “coronavirus in slow motion” did not resonate with as large a share of the full voter population (68%) as other statements. While 57% of Democrats said the message was very convincing, only 17% of Republicans said the same: For one white Democratic male Texan, “[s]low motion coronavirus is perfect,” but a white female Republican Mainer said it seemed like “fear mongering” to compare COVID-19 to climate change. An independent North Carolinian male who expressed skepticism toward climate change suggested it was a decades-old tactic to convey urgency “by making the imminent drop-dead date in the very near future.”

Despite documented overlap among the individuals who have publicly cast doubt on climate change and COVID-19, fewer voters found convincing the proposition that politicians skeptical of COVID-19 are the same ones skeptical of climate change, vaccines, and other issues where they consider themselves smarter than the experts (62%). Here, it is possible that the direct mention of climate change or other scientific areas weighed down a message that is otherwise similar in concept to the more popular sentiment on humility.

Minor Movement on Climate Action

The poll found no evidence that voters are more likely to agree that climate change is primarily human-caused if the scientific consensus, evidence, and findings of a respected scientific body (in this case the American Meteorological Society) are explicitly identified. A split-sample message test showed that 77% of voters who saw a statement with references to the AMA and to consensus agreed that climate change is primarily due to human activity, as did 75% of those who did not see those references.

However, with important caveats, the survey did suggest some movement on climate belief and urgency after respondents read certain messages.

After presenting respondents with one of the two above statements, the percentage of respondents who strongly agreed that climate change is primarily human-caused rose by 6 points, from 41% to 47%. Similarly, overall agreement (strong plus tempered agreement) with the need to act now to prevent climate change by reducing carbon pollution increased 5 points (from an initial 75% to 80%) following those statements. Much of that gain was among Republicans, whose overall agreement increased 8 points (from 55% to 63%), and independents, whose agreement increased 6 points (up 73% to 79%).

Key Messengers

Specifically on climate change, the poll suggests that generic “scientists” are the most trusted messengers on the issue, with 83% of voters saying scientists’ opinion matters to them personally either a great deal or somewhat on climate. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s climate change views were important to 79% of respondents. Smaller but sizable majorities of voters still cared about the opinions of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (76%), the American Meteorological Society (76%), and the Environmental Protection Agency (72%), but slightly less about those of local environmental groups (68%). For each of these climate messengers, a larger share of Black and Latino voters said these entities’ opinions mattered to them than did white voters.

Methodology

Third Way partnered with ALG Research on a two-part public opinion research project in July 2020. The first stage was an online focus group run through QualBoard from July 13-15. Twenty-two urban/suburban general election voters participated, hailing from Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Maine, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Wisconsin. The participant pool included a mix of males and females, age groups, races, self-identified party affiliations, and belief in the causes of climate change. A breakdown of the demographics is available here.

The second stage surveyed 1,500 likely November 2020 voters (those who said they were “almost certain” or “will probably” vote in the election) from July 23-29, 2020 (800 online and 700 by phone) in the battleground states of Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, with oversamples of 100 Black Americans and 100 Latinos. The poll uses a 95% confidence interval. The split samples referenced in the messaging section each include half of the total respondents. All results are weighted to the likely 2020 voter population in the above states by age, gender, race, education, and other demographics. Percent totals may not all add up to 100% due to rounding. Toplines and full survey results are downloadable at the top of this page.