Memo Published March 9, 2023 · 9 minute read

What is Spyware and Why Should Policymakers Care?

Mike Sexton

A weakly regulated foreign commercial spyware industry poses a direct threat to US national security and contributes to staggering human rights abuses abroad. The most infamous company is NSO Group, which was blacklisted by the Commerce Department in 2021 and featured prominently in a 2022 House Intelligence Committee hearing on the rapidly evolving threat of foreign commercial spyware. NSO Group is in turmoil as it confronts a growing list of high-profile lawsuits and its brand has become toxic among governments and the private sector. However, the commercial spyware industry broadly goes far beyond NSO Group, is likely to persist, and will repeat similar patterns of abuse unless reined in through close and coordinated regulation.

This paper explains what spyware is, what it isn’t, who some of the players are, and why it should matter to policymakers. A barely regulated international spyware industry is a crisis waiting to happen.

What is “Spyware” Exactly?

Spyware refers to:

1. commercial malicious software;

2. installed on a computer or mobile device without the user’s consent or knowledge;

3. which remotely hacks, surveils, and surreptitiously collects data; and

4. forwards that data to a third-party.

NSO Group’s flagship product “Pegasus” is perhaps the most sophisticated form of spyware on the market. It can remotely collect any and all data on a target device, including photos and videos, files, texts, contacts, and call logs. It can commandeer a smartphone’s camera and microphone to see and listen to a target, as well as monitor location, log keystrokes, and eavesdrop on phone or video calls.1

Spyware should not be confused with other tools and practices that have raised privacy concerns, but have distinct capabilities:

- User data collection is a standard industry practice for consumer technology companies like Amazon and Meta. In these cases, a user elects to install an application like TikTok or use a service like Google, and they consent to the terms and conditions or give permission to access data like one’s contacts or geolocation. Unless the company collects data that a user has not authorized – which would be unlawful or even criminal – this practice poses fundamentally less risk than spyware, which by definition is unauthorized by the user.

- The Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED), developed by Cellebrite,2 is a physical tool commonly used by police to extract data from a suspect’s device with a warrant. It requires physical possession of the device, and so cannot be used remotely or for ongoing surveillance. UFEDs and similar products carry less risk at the level of individual targets.

National Security Vulnerabilities on a Global Scale

Commercial spyware poses a direct threat to US national security because it can allow malicious foreign actors ongoing and near-total access to an American’s device. Because it is so powerful, spyware is ostensibly meant to be limited to grave national security and law enforcement cases, such as counterterrorism and human trafficking. In practice, it is often abused to track and harm journalists, political dissidents, and peaceful activists. Governments tend to use spyware to track their own citizens, however it is often deployed to track foreign targets – including outside their borders. Pegasus spyware hacked and surveilled American journalists in Lebanon3 and El Salvador,4 and even State Department diplomats in Uganda.5

The most publicized target of spyware was Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist and Virginia resident at the time of his murder. Khashoggi’s associate Omar Abdulaziz6 and wife Hanan Elatr7 were hacked with Pegasus, likely to indirectly surveil Khashoggi before his killing. But even Khashoggi is not the most high-profile individual to fall victim to spyware. Then-Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos’ iPhone was hacked in 2018, likely by an infected file sent via WhatsApp by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.8 In 2015, a company called CyberPoint indirectly spied on First Lady Michelle Obama, who was emailing with their target, the Qatari Emir’s mother Sheikha Moza bint Nasser.9

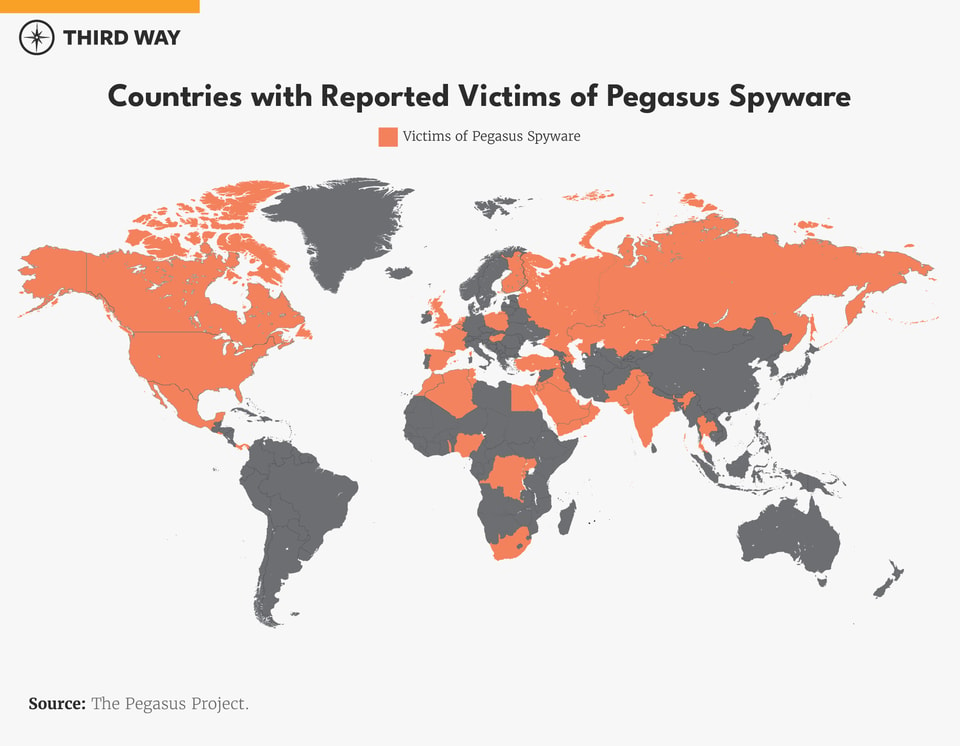

NSO Group is not the only provider of commercial spyware, but it is by far the best documented. And that is because they got caught. In 2021, a global consortium of journalists and advocates launched the Pegasus Project after poring over a leaked list of 50,000 phone numbers selected by NSO customers for surveillance. This revealed potential targets in over 50 countries.10 The consortium reached out to many of these possible targets and offered to perform a digital forensic analysis to confirm or deny if their phones were hacked. Many potential targets – especially government officials – were understandably unwilling or unable to surrender their phones to journalists. So how many of these 50,000 were actually hacked and on behalf of which client, we do not know. But this list of 50,000 is insightful to understand the massive scope of the problem: not all these people were necessarily hacked by spyware, but all of them were in the crosshairs.

NSO Group has tried not to expose the United States to its spyware by restricting Pegasus from infecting devices with an American +1 country code. However, many Americans own mobile phones with foreign country codes – and have been targeted with Pegasus as a result.11 Even if an American only has a domestic country code phone number, they can be surveilled indirectly through their contacts, as in the cases of Jamal Khashoggi and Michelle Obama. Furthermore, this restriction is merely an arbitrary decision by NSO Group, not some protection inherent to American phone networks – there is nothing stopping NSO Group’s competitors from foregoing this policy as they fill the vacuum left by its shrinking market share. Indeed, this is most likely how Jeff Bezos’s iPhone was compromised.

Filling the NSO Group Void

NSO Group’s ongoing crises may be fatal. The company was blacklisted by the Commerce Department, prohibiting it from doing any business whatsoever with American companies – including so much as purchasing smartphones from Apple or Google to test on. Soon after, the Israeli government sharply cut the list of foreign governments NSO was permitted to export to from 102 to 37.12 Facing the risk of defaulting on an estimated half-billion dollars in debt, the company has laid off one eighth of its staff and replaced its CEO and cofounder, Shalev Hulio.13

However, declaring “mission accomplished” at NSO’s demise would be premature. Several competitors with comparable advanced spyware are waiting in the wings to capture its lost market share, and there is little reason to expect them to all police themselves voluntarily. Since no one has comprehensively documented all these competitors’ tools and what exactly they can collect, assessing the counterintelligence threat is often limited to looking at the origin and location of each company, the documented hacks they’ve carried out, and whether it was based in a US ally or adversary.

Intellexa

Intellexa is a spyware firm and the parent company of Cytrox and WiSpear.14 While its founder, Tal Dilian, is an Israeli citizen and the company employs staff in Tel Aviv, Israel, the company is based in Athens, Greece, and opaquely structured with subsidiaries across Europe and the Caribbean to export its tools beyond the reach of the Israeli government. Cytrox’s flagship spyware product, Predator, is considered roughly equivalent to Pegasus in capability and has already been detected on a smartphone belonging to an Egyptian politician living in exile in Turkey.15

Candiru

Candiru is an Israel-based spyware company that was blacklisted by the US Commerce Department along with NSO Group in 2021. Whereas Intellexa and NSO evidently specialize in spyware for mobile devices, Candiru primarily offers spyware for Mac and Windows PCs.16 Microsoft’s Threat Intelligence Center has uncovered Candiru’s spyware deployed against over a hundred victims, including activists, journalists, dissidents, and politicians, in several countries in the Middle East as well as Spain, the UK, and Singapore.17

Paragon

Paragon is a secretive but apparently well-established spyware outfit. The company has no public website, but it is financially backed by the prominent American private equity firm Battery Ventures, and former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak serves on its board.18 Paragon seems intent on distinguishing itself in the field by limiting its customers to governments that respect international law and human rights. While practically every spyware company pays lip service to this principle, Paragon might not be bluffing: so far, its only publicly known customer is the US’s Drug Enforcement Agency.19 This evidently indicates that Paragon clears the bar set by Biden’s White House to ban spyware that is also used to target dissidents, civil society, or American government personnel, like Pegasus.

DarkMatter

DarkMatter is an Emirati company that specializes in cyber surveillance and functions as an arm of the Emirati government. DarkMatter grew out of an American company called CyberPoint International, staffed largely with NSA veterans, that secured US government approval to take on contracts with the UAE government. In 2015, the UAE established DarkMatter to carry on CyberPoint’s mission beyond the reach of American oversight, giving CyberPoint staff the choice to change companies or leave the UAE as it terminated its original contract. In 2021, three American ex-intelligence officials employed by DarkMatter pleaded guilty in US court to hacking crimes and violations of export law, which govern proliferation of hacking tools.20

Positive Technologies

Positive Technologies is a spyware firm and Russian government contractor blacklisted by the Commerce Department. The company has stated that 97% of its revenue comes from Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States – an association of former Soviet states that remain politically aligned with Russia. Ensconced thusly within Russia and its geopolitical periphery, the company has dismissed the importance of the blacklisting on its continued business.21

Conclusion

Spyware epitomizes the dilemma of “dual-use” technologies – it can be a breakthrough for law enforcement and intelligence for maintaining wiretap capabilities in a digitized world with ubiquitous encryption, but presently – without regulatory guardrails – it primarily acts as a superweapon wielded by authoritarians and corrupted democracies to surveil, harass, intimidate, and even kill their critics. A wider understanding of this technology and market – beyond NSO Group – is necessary to sustainably prevent these abuses.