Primer Published March 7, 2019 · 17 minute read

Thematic Brief: US Cybersecurity Efforts

The National Security Program

Takeaways

Cybersecurity—ensuring malicious actors cannot harm us online—is a top national security issue for the United States. Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats highlighted the current cyber threats that the United States is facing, stating the “warning lights are blinking red.” A wide range of actors, including nation-states, terrorist and criminal groups, and lone actors, have launched cyberattacks and committed cybercrime over the Internet, causing devastating impacts to US national and economic security.

Unfortunately, the Trump Administration’s cybersecurity efforts lack cohesiveness and effectiveness, starting with President Trump’s refusal to acknowledge Russia’s interference in America’s 2016 presidential election, which utilized cyber tools to spread disinformation and hack into election infrastructure and Democratic Party accounts. While Congress has pushed for more legislation in recent years, these efforts do not reflect a comprehensive strategy to impose consequences on malicious actors.

To strengthen the US government’s efforts to combat malicious cyber activity, Congress must now take action to:

1. Improve the US government’s capabilities to identify, stop, and punish human cyber attackers in order to close the growing cyber enforcement gap: the number of cyberattacks launched per year in the United States versus the number of arrests of malicious cyber actors;

2. Invest in securing America’s election infrastructure and combating foreign disinformation efforts; and

3. Re-establish the United States as a global leader in setting policy around how different actors should behave in cyberspace and boost international cooperation and capacity around these issues.

Cybersecurity is a top national security issue for the United States, with cyber threats posed by a wide range of actors causing devastating national and economic security consequences.

Malicious cyber activity, including cybercrime, has caused devastating impacts to US national and economic security. This activity continues to grow and evolve. According to recent polling Americans view malicious cyber activity as their top security concern, ahead of the economy, nuclear threats, and ISIS.1

The cyber threat affects all sectors of the economy in the United States and globally. A single cyber incident can disrupt thousands of systems worldwide and cost millions of dollars. For example, the NotPetya cyberattack, the most damaging in history, caused over $10 billion in damage.2 The White House Council of Economic Advisors estimated in 2016 that malicious cyber activity costs the US economy between $57 billion and $109 billion per year.3 Other estimates put the number as high as $3 trillion for the global economy annually.4 Because of the borderless nature of cyberspace, a single cyber incident can impact victims in many different countries and can be committed by a perpetrator who is not in any of these locations.

Beyond financial harm, cyberattacks are a serious threat to US national security. Malicious cyber actors have attacked health care systems and critical infrastructure in the United States, such as Industrial Control Systems (ICS), the electric grid, and dams. A successful attack executed on these systems can threaten life and property, and cause large-scale destruction. Hostile nations have used cyberattacks to halt the operations of, and steal sensitive information from, critical US national security institutions and personnel.5 For example, in 2014 and 2015, the Office of Personnel Management suffered a massive data breach exposing the sensitive information of up to 22 million people, including personal information in their security clearance forms.6 Terrorists and illicit criminal networks have continued to use the Internet as a key operational tool, presenting a threat to US national security.

Perhaps most alarmingly, Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election—in which they used malicious cyber tools to spread disinformation and hack into election infrastructure and Democratic Party accounts in favor of then-candidate Donald Trump—demonstrates the grave danger cyber threats can pose to US national security and confidence in American democracy.7

Of particular concern, there is a burgeoning cybercrime wave in the United States. Cybercrime are crimes that use or target computer networks no matter the perpetrator, and can include such things as data theft, fraud, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, worms, ransomware, and viruses.8 The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) received more than 300,000 reports of cybercrime via its Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) last year.9 Since the FBI estimates that only 15% of victims report incidences of cybercrime, that number is probably a vast undercount.10 Cybercrime is a major concern to the US government because malicious cyber actors have been able to commit criminal activity, such as stealing assets from America’s largest financial institutions, over the Internet. Cybercriminals also benefit from the high demand for malicious cyber tools from nation-states like Russia, Iran, and North Korea, who use these tools to perpetrate attacks on US institutions and people.11

The Trump Administration’s cybersecurity efforts lack cohesiveness and effectiveness. Congress has done little to strengthen the US government’s response to cyber threats.

Despite the growth and evolution of cyber threats, the Trump Administration’s approach has lacked coherence. The Administration’s strategy to combat this threat has not matched with the president’s words and deeds.

The US Intelligence Community (IC) has unanimously concluded that Russia launched malicious cyber operations to influence the outcome of the 2016 presidential election.12 Yet President Trump continues to deny their involvement, undermining the position of the IC and hindering our ability to work with international partners to combat this threat.13 The president has also resisted imposing sanctions on Russia for its meddling in the 2016 election, despite pressure from Congress. The “Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act” (PL 115-44) set a deadline to impose sanctions on Russia for their involvement in the 2016 election. The Administration missed the deadline by several weeks, but eventually bowed to the pressure and agreed to impose the sanctions.14

Further, while the Trump Administration has taken important steps to expand the US government’s cyber efforts—including by indicting a number of malicious cyber actors and creating new cyber threat information-sharing mechanisms for the private sector—the Administration’s recently released National Cyber Strategy lacks a comprehensive approach to addressing this threat and does not meet the benchmarks for an effective strategic approach that allows for proper oversight.15 While the National Cyber Strategy is an important first step, it centers heavily on cyber defense (i.e., trying to protect Americans from attacks) with only a few short sections committed to pursuing the attackers themselves. It proposes no advances in how the government will assess its progress in combating cyber threats and has few innovative, new solutions to address the number of tremendous challenges that exist in doing so.

The Trump Administration is actively undoing the progress made in recent years to establish such leadership. In particular, the Administration has eliminated two key positions on cybersecurity. First, it eliminated the White House Cyber Coordinator position within the National Security Council (NSC), leaving coordination to two senior director-level NSC officials.16 Second, it downgraded the State Department’s Coordinator for Cyber Issues.17 The Office of the Coordinator for Cyber Issues at the State Department was established by the Obama Administration as the first senior-level position and office at the State Department working to advance America’s diplomatic efforts on cyber issues and build the capacity of our nation’s diplomats to deal with these threats.

Congress must hold the Trump Administration accountable for its lack of clarity and consistency in its cyber approach, and push for an aggressive and comprehensive cybersecurity strategy for the United States. However, the 115th Congress fell short in these efforts. A Third Way analysis of over 200 pieces of cybersecurity-oriented legislation introduced in the last congressional session shows that more than 87% of the proposed bills focus on defensive measures like information sharing, breach notifications, and investing in better infrastructure. The Senate was too often an impediment to new legislation; 42 bills did not receive a vote in the Senate after passing the House.

Defensive-oriented efforts are critical and deserve much larger support. But they must be balanced with a focus on policies that also help the United States stop, identify, and punish malicious cyber actors and reduce the current level of impunity. Further, the few bills that were introduced in the 115th Congress that are designed to impose consequences on aggressors or boost international cooperation to this end—such as the Cyber Deterrence and Response Act (H. R. 5576) and the Cyber Diplomacy Act (H.R. 3776)—failed to make progress and deserve reconsideration in the 116th Congress.

Congress must now take action to strengthen the US government’s efforts to combat malicious cyber activity.

To strengthen the US government’s efforts to combat malicious cyber activity and create coherence and effectiveness in the government’s approach, Congress must now take action to:

1. Improve the US government’s capabilities to identify, stop, and punish human cyber attackers in order to close the cyber enforcement gap.

The United States is facing a rising and often unseen cybercrime wave. Yet Third Way’s research has found that cybercriminals operate with near impunity compared to their real-world counterparts. Right now, the United States is as far from a comprehensive strategy aimed at identifying, stopping, and punishing malicious cyber actors as the nation was from a strategic approach to countering terrorism in the weeks and months before 9/11. Congress must work to address this by putting in place the foundations for such a strategy.

Third Way has launched a new Cyber Enforcement Initiative to help Congress do just that.18 Our research estimates that for every 1,000 cyber incidents, only three ever see an arrest—what we call the cyber enforcement gap. That is an enforcement rate of 0.3%.19 By comparison, the clearance rate for property crimes was approximately 18% and for violent crimes 46%, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report (UCR) for 2016.20

The United States requires a rebalance in its cybersecurity policies: from a heavy focus on building better cyber defenses against intrusion to also waging a more robust effort to go after human attackers. Achieving this would require a more balanced approach that places much more emphasis on law enforcement and diplomacy, while preventing the overreliance on the military that currently exists. Rather than responding to cyber threats that come into the United States with military operations, the US government should and can use its Title XVIII authorities to bring law enforcement to bear against the attacker at any time. Unfortunately, the current prioritization undervalues and underinvests in that response. We can only stop the cybercrime wave and close the cyber enforcement gap by transforming law enforcement, enabled by diplomacy, to go after the human beings perpetrating or ordering attacks.

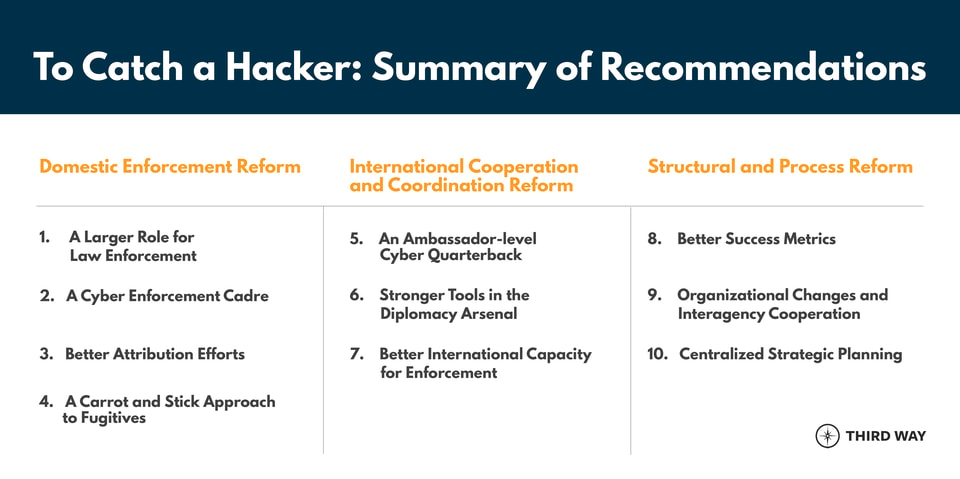

Third Way has established 10 policy areas that require urgent attention from Congress in order to reduce the cyber enforcement gap:

As a first step, Congress must work to establish a baseline to understand the scope of the cyber enforcement problem. This will lay the foundation for a comprehensive strategy aimed at closing the cyber enforcement gap. There must be a comprehensive assessment of current government efforts across all agencies with a role in cyber enforcement to determine what is working, what might need to be amplified, and what might need to change. Establishing a baseline would include requiring a government-wide assessment of the current levels of US law enforcement actions, as well as an analysis of the amount and effectiveness of support provided to other countries by the US State Department to build their capacity around cyber investigations. Without baseline statistics, it is difficult to measure government efforts, develop budget estimates for current levels of effort, or make an informed case for budget increases necessary to support increased enforcement levels. Congress can address this by mandating these baseline assessments and pushing for cyber enforcement agencies to establish better metrics to measure the extent of the problem.

2. Invest in securing America’s election infrastructure and combating foreign disinformation efforts.

As America’s adversaries have utilized malicious cyber tools and information warfare to attack the United States, undermine its institutions, and sow discord, Congress needs to forcefully push back and invest in securing America’s election infrastructure and combating disinformation efforts at all costs.

In 2016, the IC concluded that Russia attempted to not only influence the outcome of the US presidential election, but also inject public distrust in our democratic institutions and electoral systems. Russia took a series of actions aimed at boosting the candidacy of Donald Trump, who was seen as more likely to serve Russia’s interests. The indictments from the investigation led by Special Counsel Robert Mueller demonstrate how Russian agents hacked the Clinton campaign, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, and the Democratic National Committee in multiple operations.21 The emails stolen from these hacks were then published on the website WikiLeaks in an effort to publicly undermine the candidacy of Hillary Clinton.22

While the leaked emails received plenty of press coverage, Russian operatives also targeted election infrastructure. They breached the voter databases and websites of seven states in the run up to the 2016 election.23 There is no evidence these databases were manipulated, but the Russians clearly showed they have the capability to do so. Congress must take action to protect US election infrastructure from future interference and disruption.

Despite a renewed focus on election security before the 2018 midterms, US election infrastructure and mechanisms remain woefully inadequate. Russia’s hacking into state election databases shows the vulnerability of election security systems to manipulation. Further, most information security experts agree that paper backups for ballots are crucial for election integrity and the ability to perform accurate and trustworthy audits; yet five states in the United States do not use paper backups.24 The technology used to vote in some states is also often outdated and unreliable.25 Congress has only allocated $380 million to help states strengthen and modernize their election security systems after the 2016 election. After the voting irregularities of 2000, Congress had allocated an amount 10 times greater.26

Unfortunately, congressional Republicans have stymied efforts to provide more funds for election security and give states the critical resources they need to protect future elections.27 House Democrats have now introduced the “For the People Act” (H.R.1), which contains substantial funding for election security and makes paper backups compulsory for all federal elections.28 The bill is an important first step to ensuring safe, secure, and reliable American elections and instilling public confidence in US democratic institutions.

Additionally, Congress must work to combat foreign disinformation campaigns aimed at sowing division among the American public and injecting doubts in voters’ minds about their democratic systems. Russia’s efforts to interfere in the 2016 US presidential election included exploiting social and traditional media platforms, including widely utilized platforms such as Facebook and Google, to promote propaganda and spread false or misleading information through the use of fraudulent accounts and advertisements.29 The IC has concluded that Russia’s disinformation campaigns were aimed at supporting the candidacy of Donald Trump.30 However, Russian operatives often did so by talking less about the election itself. Instead, they focused on issues that have prominence in current US political debates, such as gun rights and support for veterans, with the goal of dividing the American public against each other and promoting Donald Trump’s positions on these issues.31

Countering foreign election interference efforts will require dedicated action from policymakers, working in coordination with private sector companies whose platforms are used to spread disinformation. Members of Congress must educate the public about Russian disinformation efforts and condemn President Trump’s attempts to ignore or downplay them. Congress must also work to assess whether the US government has all of the tools it can possibly use to combat foreign meddling in America’s elections. The Department of Defense has expanded its cyber operations targeting Russian hackers and agents with “digital alerts,” letting them know that the US government can see what they are doing. Congress must evaluate whether these efforts are having enough impact in deterring Russia and other foreign actors from using malicious cyber tools to interfere in US elections.32

Action is also required from technology companies to shore up their defenses against foreign influence operations and protect against the spread of disinformation. These companies have a responsibility to protect their users from these efforts and to crack down on malicious cyber actors that use their platforms to meddle in democratic elections and divide societies. Bills such as the “Honest Ads Act” (S. 1989), demanding more transparency for election-related advertising on online platforms, are a step in the right direction.33 That act is now a part of H.R. 1, along with a number of other election security and voting measures that should be made into law.34 Congress needs to ensure that social media companies are stringent in enforcing policies that prevent the spread of disinformation and use of fraudulent accounts on their platforms.

3. Reestablish the United States as a global leader in setting policies on behavior in cyberspace and boost international cooperation and capacity on this issue.

The global nature of the cyber threat requires dedicated and deliberate leadership and coordination at the highest echelons of the US government. Given the scope of countries that are impacted by cyber threats, little progress can be made in America’s cybersecurity efforts if our cyber diplomatic and development efforts are not expanded and ties to partner nations around the globe are not strengthened. To catch international cybercriminals, America needs a coordinated international effort and cooperation on cyber investigations.

A congressional authorization to elevate the Office of the Coordinator for Cyber Issues at the State Department is a good first step, but it is not enough. The office must also be provided with a clear mandate that includes a focus on closing the enforcement gap, strengthening its efforts to identify the perpetrators of cyberattacks, and implementing diplomatic training programs. It must also be provided by Congress with the necessary resources and personnel to be able to implement those initiatives. This is critical to drive forward a rebalance in America’s cybersecurity approach to one that puts the State Department front and center as a key entity for progress.

Additionally, Congress must provide adequate resources to global cyber capacity-building efforts. Currently, the United States provides capacity-building assistance to countries on cybersecurity and cybercrime through US diplomatic, development, and international judicial programs. It is clear that the current levels of funding and manning for capacity-building efforts are not adequate to meet the challenge. To strengthen the capability of partner nations, the US government must assess and expand its support of global cyber enforcement capacity building. It must help foreign authorities understand and address cyber threats as it also works to strengthen its own cybersecurity efforts.

Conclusion

The United States is facing a burgeoning cybercrime wave, and we do not have a cohesive strategy to combat it. Malicious cyber activity costs the United States between $57 billion and $109 billion each year, and may cost trillions of dollars globally. It poses a serious national security threat—we have already seen attacks not only against private technology companies, but also the electrical grid, election systems, health care systems, and government agencies. Still, only three in 1,000 cyber incidents result in an enforcement action. We must do more to identify, stop, and punish malicious cyber actors.

While the Administration has made a number of indictments through the Department of Justice, their approach to this threat remains incoherent and inadequate, starting with the president’s refusal to acknowledge Russia’s attempt to influence the 2016 presidential elections. The Administration has eliminated critical positions from the White House and the State Department, undoing the progress made in previous administrations. Congressional Republicans, along with the White House, have impeded substantial investment to secure our elections.

Congress has an opportunity to assert its authority and act in our national security interest by taking these three steps: 1. improve the US government’s capability to identify, stop, and punish malicious cyber actors; 2. invest in election security and combatting foreign influence operations; and 3. reestablish the US as a global leader in cyberspace.