Report Published July 17, 2024 · 28 minute read

Competing Values Will Shape US-China AI Race

Valerie Shen & Jim Kessler

President Biden’s AI executive order reflects a set of values recognizable to all Americans: Privacy, equal treatment and civil rights; free speech and expression; the rule of law; opportunity and free market capitalism; pluralism; and advancement of global leadership as the beacon of a free world.

President Xi Jinping’s government has also issued AI regulations with values recognizable to China: Collectivism and obedience to authority; social harmony and homogeneity; market authoritarianism and rule of state; and digital world hegemony to restore China’s rightful place as the Middle Kingdom.

The United States and China may share similar broad goals for “winning” AI along the lines of leading innovation and advancement, spurring broad-based economic growth and prosperity, achieving domestic social stability, and becoming the clear global influencer for the rest of the world—but they define those goals and seek to achieve those ends through very different values. Those values embedded in our respective AI policies and underlying technology carry high-stakes, long-term national and economic security implications as US and Chinese companies compete directly to become dominant in emerging global markets.

They also share similar fears that reflect each country’s values. China worries that AI could cause social unrest if information to a sheltered population is too real and unfiltered. America fears that AI could cause social unrest if information Americans receive is too fake. And that massive disinformation and algorithms that rile the population could threaten our democratic system.

Why do these value differences matter when it comes to the AI race? Below, we outline six contrasting values that we believe will be the most determinative in how the US-China AI competition plays out. We argue that understanding our different values-based approaches illuminates our respective advantages and disadvantages in this competition. It assesses who is currently set up to “win” across key metrics and determines how to lean into our democratic advantages or mitigate some practical disadvantages compared with the PRC, this will ultimately win the AI marathon.

Free Market vs. Market Authoritarianism

America has prospered over the nascent internet age, but not without troubling trends that could explode in the AI era. Over the 30 years since the Internet was released to the public, the US economy quadrupled in nominal size and per capita income tripled. However, wealth and opportunity concentration also multiplied. The richest American in 1993 would only be the 44th richest today in inflation-adjusted dollars. There are now 735 billionaires, more than double that of 1993 in today’s dollars. Eight of the 10 richest people in the US made their eleven-figure fortunes in tech, as did 69 of the Forbes 400 with a combined worth of $300 billion.

Meanwhile, the gains for the middle class were not so stellar. During the same 30 years, real median household income grew a middling 32%. One-third of US counties are economically distressed, according to a 2024 Brookings Institute report. More than half of US counties experienced a decline in the number of businesses up and running between 2000 and 2019, and nearly half of all counties had fewer people employed at the end of that same two decade stretch compared to its start.

MIT economist Daron Acemoglu estimated “50% to 70% of the changes in the US wage structure are intimately linked to automation, particularly digital automation.”1 Notably, most of the benefits in the US wage structure accrued to the two-fifths of working age America with a college degree, meaning the distribution of economic benefits was not a “rising tide lifts all boats” situation.

There are those who believe opportunity will spread on its own with a light touch from government. That seems improbable.

Without a concerted effort an AI technology revolution will further concentrate wealth and opportunity. A thoughtfully regulated free market to simultaneously grow the pie and level the economic playing field driven by AI is the core economic challenge for the US. Public policies must overtly steer AI to fulfill the promise of spreading economic opportunity across all socioeconomic statuses. Policies so people can earn a good living no matter where they live or what degree they hold—will be hotly debated topics in the halls of Congress, academia and the private sector. Tech companies will need to be intentional as well with their investments and how new discoveries increase or take away the ability for people to earn a good living where they call home. It will take myriad solutions that address place-, race-, and education-based disadvantages to keep America the land of opportunity in the AI era.

In China, winning the AI race is critical, but “information control is a central goal” of the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) generative AI measures implemented thus far, wrote Matt Sheehan in a Carnegie Endowment report. Information control and innovation are not naturally compatible. CAC officials emphasized in the guidelines themselves how AI software “should reflect the core values of socialism” indicating a core driver to keep AI in line with the government’s political values and status quo power structure.2

When Mao Zedong took power in 1949, China was one of the poorest countries in the world, with only 10 other countries having a lower per capita GDP. It was not until Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping enacted market reforms in 1978 that China began transforming from an impoverished nation to the second largest economy in the world. Using the World Bank’s standard, China’s national poverty rate fell from nearly 90% in 1981 to under 4% in 2016, with an estimated 800 million fewer Chinese people living in poverty.

Nevertheless, today’s Chinese government still uses “capitalism” as a bad word and economic success and artificial intelligence are twin-edged swords for Xi Jinping, who prizes regime preservation above all other goals. In 2021, Xi Jinping largely revived old anti-capitalist Maoist slogans on “common prosperity” and pledged to “regulate excessively high incomes” while promoting fairness and balance in China’s economic growth. A strong middle class didn’t exist in Mao’s China but does today. So when Xi revived the “common prosperity” phrase in 2021, it was because a capitalist-style period of growth created an affluent class in China that Mao could never have imagined. And along with it, threats of political polarization and social divisions that are anathema to the Party. The fear of unrest stemming from economic inequality is so great that China’s censors crack down on both evidence of the still widespread rural poverty and displays of the wealthy’s lifestyles deemed too hedonistic to the larger populace.

It is not a coincidence that the Chinese economy slowed under Xi Jinping. There are many factors—from mishandling COVID lockdowns to a massive debt overhang and greater global competition. Xi’s key impediment lies in the tension between the vast inefficiencies China’s market authoritarianism is doomed to make and regime preservation which is prized above all else. Xi wants to keep absolute power with he and his party maximizing its hold over private companies and citizens. Packaged with all of the opportunities AI presents for China is also the threat of AI to the party itself with the technology potentially loosening the government’s grip over society.

The Chinese government is making a conscious effort towards directing AI advancement in the private sector from undermining the near-total control of its military-civil fusion model and preventing any cracks in its overarching surveillance of the domestic population. This approach is certainly not without economic costs.

All told, fundamental differences in our respective economic systems define the US-China technology competition. The US has long-championed a free marketplace of ideas without heavy-handed government intervention as key to successful American innovation and progress. While China’s economic boom is rooted in the Chinese government embracing more capitalistic practices, they still deploy centralized, autocratic power in their market—sometimes contributing toward greater global competitiveness, but sometimes undermining this goal in pursuit of other national priorities.

The American free market system looks well-positioned to maintain a structural economic competition advantage over China. Looking forward, American policymakers should also focus on mitigating the social consequences that will accompany the inevitable cases of worsening opportunity inequality. To the extent there are fears American efforts to correct our free market in this way will slow down the AI economic boom, they should be tempered by knowing Xi Jinping and Chinese governments have generally shown a far greater willingness to be domineering over their private sector and society, even at the cost of hindering their own economic system in the global AI race.

Rule of Law and Checks & Balances vs. Rule of State and Top Down Authority

China’s centralized, top-down system has advantages in speed and for long-term planning as demonstrated by their many government initiatives from the Digital Silk Road Initiative to Made in China 2025. However, China’s approach has also undermined overall global competitiveness in favor of greater government control over its businesses and people.

In 2020, the Chinese government began a stunning wave of regulatory crackdowns wiping $1.1 trillion from its own Big Tech industry and shaking the confidence of foreign investors. The crackdown commenced when the 2020 IPO for Ant Group was pulled because of remarks by its CEO Jack Ma that Xi deemed too dismissive of the regime. Companies and entire industries were targeted for sins ranging from speaking out against CCP policies, listing their company overseas, or for a perception of contributing to social problems.

China’s quest for global data supremacy attempts to seal off the potential flow of its sensitive information to foreign governments and investors, but some foreign firms have been pulling out their business amidst harsh and seemingly arbitrary crackdowns. China’s intellectual property, data privacy, and counterespionage laws are by design vaguely worded to give Chinese officials broad discretion over when and how to use them. The foreign business community is also subject to unpredictable security checks, with Chinese officials questioning and even detaining employees without any explanation.

All of this means that Chinese AI regulations will move far quicker than in the US but carry far more ambiguity. Internal crackdowns on the tech, finance and real estate industries occur regularly and capriciously in China. Rule of law is less certain, generating the kind of instability for companies that a cohesive regulatory regime is supposed to avoid. Innovation may be perpetually held back as generative AI, at least initially, seems more suited to an uncensored world.

By contrast, America’s system for tackling cutting-edge, deeply complicated laws and regulations is a cacophony. Typically, it involves the entirety of key stakeholders—government, private sector, civic society, and more—and develops policies that check and balance against each stakeholders’ interests and concerns.

As a result, when it comes to setting the global rules of the road with robust generative artificial intelligence legislation and regulations, the US is clearly behind China (as well as the European Union). There is currently nothing close to a primary agency for AI in the United States; China’s clear bureaucratic leader is the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). In the past few years, the CAC has passed major generative AI measures including regulating the use and misuse of AI recommendation algorithms in 2021, synthetically generated or “deepfake” content in 2022, and comprehensive generative AI regulations in 2023 targeting technological exports, global AI research, and AI products like ChatGPT.

The US is, thankfully, out of the starting gate. Last fall, President Biden released an exhaustive AI executive order. Senate Majority Leader Schumer is leading a bipartisan Senate effort to regulate AI legislatively. The House of Representatives is moving forward with its own legislation. Several states are moving ahead with laws and regulations. Lobbyists, think tanks, and civil society advocacy organizations are weighing in with thoughts, ideas, fears, and hopes. Yet, somehow this mess not only works, it is a key American value and advantage.

The US wants private industry to succeed and innovate and for America and its companies to unquestionably lead the way. Checks and balances and rule of law let us move forward with certainty and responsibly—albeit haltingly and argumentatively. Compared with the capriciousness with which China administers its laws, a predictable legal system is one of the great unsung assets America has to win the global AI competition. That is why the bipartisan efforts in the Senate and House to place guardrails on AI is not only important for the safety of artificial intelligence breakthroughs, but for the economic benefits as well.

America is clearly behind and should do whatever is practical to prioritize AI regulatory efforts that establish meaningful guardrails. With the right amount of motivation and pressure, Congress will at some point agree on a series of imperfect laws that the President will sign. Companies will complain, courts will weigh in, lawsuits will commence, regulations will be dissected and through it all billions, if not trillions, in investments will pour into the United States. America can’t be complacent in inevitable victory, but we should also have faith that our messy rule of law makes America the best place to take a risk and avoid cutting corners simply in the name of speed.

Privacy and Equal Treatment vs. Collectivism and Deference to Authority

AI innovation relies heavily on big data sets in the form of Large Language Models (LLMs), and this front in the AI race is fueled by drastically different values between the US and China toward protecting personal data and ensuring equal treatment of all individuals. Compared to Americans, Chinese nationals are far more willing to allow large-scale data collection, stemming in part from deep-seated cultural values of collectivism—prioritizing community goals over personal rights and interests, and a far greater willingness to submit to a big data surveillance state because they trust the authority running it.

Tech venture capitalist Kai-fu Lee argues China’s advantage is access to the most data possible, where China is the Saudi Arabia of data and its tech sector is well prepared to marshal whatever computing power is needed to out-train Western AIs by brute force.3 Much of this advantage stems from China’s tremendous mass surveillance state, enabled by a greater societal collectivist willingness to respect and obey authority. For centuries, China’s cultural and political attitudes have reflected Confucian ethics that emphasize self-sacrifice on behalf of a larger whole.

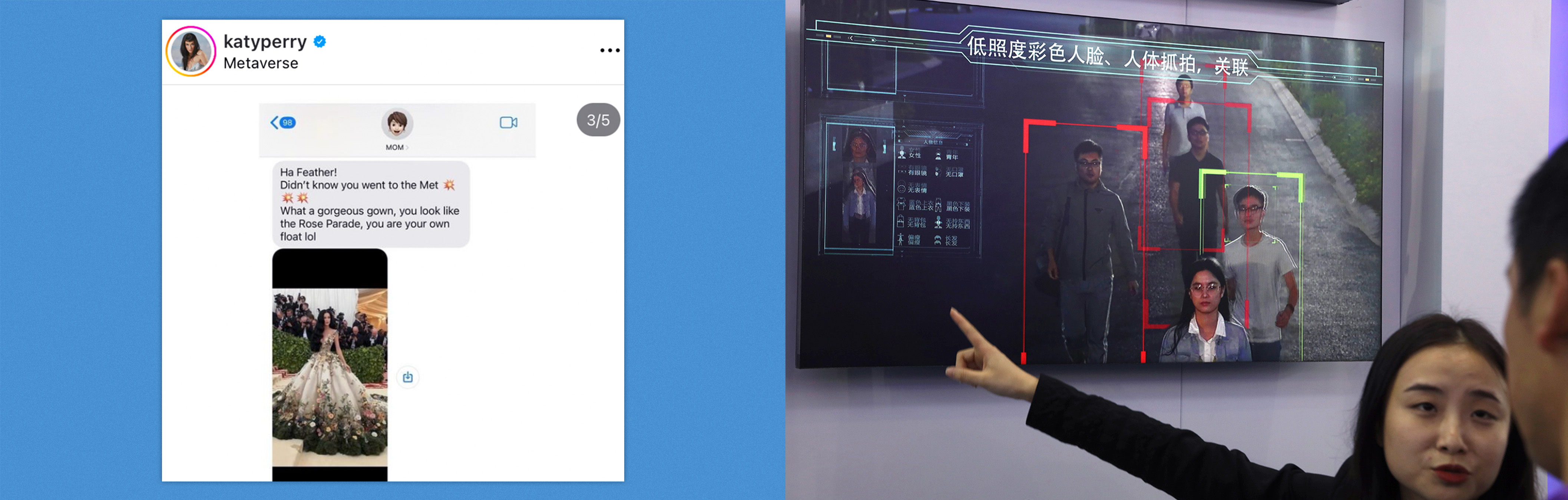

These attitudes persist today. The political consulting firm Edelman recorded a decade-high 91% trust in the China’s government amongst its citizens in 2022, compared to 37% in the United States. Despite the widespread Western reaction of China’s pervasive surveillance state and social credit system as a dystopian nightmare, there is high general support among Chinese citizens, correlated with higher political trust in the regime.

Chinese people have a weaker sense of individual, personal ownership when it comes to data—and are thus far more likely to give others control or access. In a 2022 survey of Chinese consumers, only 19% said they were unwilling to provide personal information in order to receive quality, personalized services. An Australian Strategic Policy Institute study found widespread acceptance and even expansion of existing surveillance and data collection measures such as DNA collection and facial recognition software. When asked specifically about surveillance cameras in their community, 39% supported the same number of cameras while 38% supported even more of them.

Americans will never accept the collection of personal data on the centralized, large-scale model the Chinese government employs: Constant online and offline data collection of smartphones tracking everything from iris, fingerprints, DNA, gait-analysis, and voice recognition to financial transactions, daily trips, social connections, installed apps, and more. And the risks of data collection extend beyond smartphones. As AI becomes more integrated into ubiquitous consumer technologies like connected and autonomous vehicles, the opportunities for pervasive surveillance and data collection from bad state actors will grow even more—something American consumers will consider alien to their values.

Americans highly value information privacy in the age of big data, with a 2015 survey finding over 90% of Americans thought it was “very” or “somewhat” important for them to control who had access to their data, and what information is collected about them. 70% of Americans also expressed distrust in leaders of both private sector companies and the government to handle their data responsibly in the context of AI. More data from more people gives China a comparative advantage in domestic users and sheer depth of detail into one individual user’s daily activities through their smartphone alone.

But the US has other advantages. It is uniquely diverse across racial, ethnic, religious, and sexual orientation dimensions so there is a richness in the quality of our data. The value of equality and civil rights presents significant but necessary complications when developing an AI regime with algorithmic fairness.

Handled as an afterthought, AI could further entrench discriminatory harm in employment, housing, education, criminal justice, and more. Many AI systems are notoriously error-prone based on sexism and racism – denying housing to renters who can afford rent, or falsely “predicting” crime upon innocent citizens. Just as it is illegal for companies to discriminate against customers, AI products will inevitably face government scrutiny to prevent discriminatory AI products from running rampant. The government in turn will need to meet the challenge of holding companies accountable by enforcing rules to ensure tech giants develop responsible AI without ultimately stifling competition and innovation.

By contrast, China has never championed equal treatment across its minority groups, instead pursuing forced assimilation and conformity as its stated public policy goal. Not only is the Chinese government merely uninterested in protecting vulnerable minority communities from disparate treatment in AI, they have notably used the Uyghur Muslim minority as an involuntary data source to hone its racial profiling technology and intentionally further entrench their discriminatory practices.

The Chinese government does not have to deal with the same American challenges of protecting individuals against misuse of data and collection, but America’s actual diversity in citizens also provides a comparative advantage against China’s relative lack thereof. It is not just volume, but quality of data collection that will help the US win the AI competition. As the old technology saying goes, “garbage in, garbage out” and nowhere is this more true than in AI data collection.

So despite China’s comparative advantages in quantity and depth of data for AI training, the US can and should continue to compete instead by focusing on data quality for more effective, open and transparent algorithmic data learning models.4 In the context of data, strong expectations of individual privacy limit the domestic ceiling on volume, but the industry can also pursue data collection from our international partners to mitigate this disadvantage. US diversity and commitment to protecting every individual’s rights cuts both ways from a pure competition perspective, but is also a defining, unchangeable aspect of US values that we should continue to champion in its own right.

Free Speech and Freedom of the Press vs. Social Harmony and Stability

The United States has the strongest free speech and press rights of any nation, but our First Amendment presents unique challenges in how to keep our media landscape based in reality and not in misinformation or nefarious influence operations. China’s infamous Great Firewall is the world’s most sophisticated, penetrating censorship regime and supported—or at least accepted in large part from the longstanding Chinese value of social harmony and stability.

Between the US and China, which content-moderation model will ultimately prove the most sustainable and successful in the AI competition? Both involve societal harms that risk to destabilize, delegitimize, and substantially weaken the power and influence of each respective system.

AI-generated content from deepfake photos and videos to new LLM-based chatbots pose novel misinformation and disinformation threats to the common reality that is at the foundation of a functioning democracy. AI could supercharge America’s struggle to reconcile powerful values such as free speech and political expression with preserving a shared sense of truth amidst ever-growing deepfakes and disinformation. Conspiracy theory communities like QAnon and the massive, ongoing election fraud disinformation campaign of former president Trump led to one of the darkest days in US democracy on January 6, 2021.

Because LLM-based chatbots are trained on texts that can include many forms of biases or may originate from conspiracy theories, this automates and increases the risk of propagating and entrenching that misinformation. Chatbots can also be weaponized to supercharge nefarious actors propagating disinformation by producing biased or fake news and narrative for sockpuppet social media accounts at massive scale. A 2019 OpenAI paper warned that the tool could fall into the wrong hands and “lower costs of disinformation campaigns” and aid in malicious pursuit of “a particular political agenda” or “to create chaos or confusion.”

Regulating content and social feeds have, and will continue to face political and legal challenges. In 2023, the Supreme Court sided with YouTube that they should not be legally liable for videos its algorithm recommends based upon the immunity Section 230 gives companies that host third-party content in the digital age.5 One year earlier, the Department of Homeland Security disbanded its Disinformation Governance Board over criticism that the US government has no business dictating the “truth.”6 In other words, the US government does not currently have strong legal or institutional capacity in place to combat disinformation at scale.

As a result, leading AI companies are trying to self-govern with serious research attempts to readily identify and expose deep fakes. Chatbot developers are also seeking to classify misinformation and extremist rhetoric as abusive behavior in their user policies and ban users who repeatedly violate it. Despite meaningful public-private sector cooperation and engagement, without a regulatory regime the US still has limited tools to ensure a core, shared truthful reality to stifle radicalization while protecting the free speech rights of Americans.

By contrast, the PRC has many censorship tools to enforce at least its version of government-backed truth. China’s rule of state and top-down regulatory model prioritizes civic harmony—accomplished by a synthetic information environment designed to protect and advance CCP ideological hegemony. One of the direct justifications for China’s censorship model is the pursuit of a “harmonious society” as championed by former Chinese President Hu Jintao. This political strategic goal emphasized stemming “social discontent” from rising inequality, resolving underlying “contradictions,” and maintaining social stability. In practice, this often manifested as the Chinese government suppressing and censoring media, voices, and dissent.

The concept of "harmony" is so closely tied to Chinese censorship that in Mandarin, the phrase “river crab” is used as slang for Internet censorship because it sounds similar to the Mandarin phrase for “harmony.” Chinese bloggers will often remark they “have been harmonized” when their posts have been deleted in Chinese cyberspace. Chinese regulations require that recommendation algorithms “uphold mainstream value orientations” and “actively transmit positive energy,” and companies maintaining these algorithms must intervene manually if their trending topics are harmful to the government’s interest.

As Matt Sheehan of the Carnegie Endowment points out, China’s first AI regulation came in 2021 as it intervened to assert government control over recommendation algorithms specifically.7 For its own goals, China’s censorship regime and top-down state media serve for better message control over society and collectivism. And nationalism leads to less risk of destabilizing protest.

The Chinese government has pioneered some of the world’s most restrictive AI regulations for chatbots and other generative AI applications such as AI-generated deepfakes. The regime simultaneously weaponizes AI to turbocharge its own malign influence operations such as denying the Tiananmen Square massacre, claiming CCP sovereignty over Taiwan, and characterizing independence movements in Tibet and Hong Kong as terroristic.

Unlike the US, the PRC has a strong set of tools to target and combat dis- and mis-information. But they are only in the business of countering and enforcing against information that criticizes the Chinese state or threatens their propaganda narrative—regardless of where “truth” lies. For example, Chinese censors worked at the highest “emergency response” level during the crackdown of zero-COVID protestors in 2022 amidst widespread frustration of Xi Jinping’s signature domestic policy.

The protests themselves erupted in part due to the disconnect of Chinese censors and sunny state narratives trumpeting the success of the zero-COVID policy against the Chinese citizens’ dystopian reality of government lockdowns, food shortages, and 2 million preventable deaths from lack of medical care. Although the PRC did successfully crack down on the protests, it left the world gaping at the organic and explosive social anger that most did not think could happen in China’s controlled society—a true failure of the PRC’s stated goal of social harmony.

Dramatic social instability has plagued the US by arguably under-correcting for disinformation in the January 6, 2021 attack, and in China for over-correcting in censorship of inconvenient facts in the zero-COVID protests. While Americans justifiably value free speech and political expression, AI advancements have greatly lowered the barrier of entry for dangerous disinformation in society. The US should redouble its efforts to create government systems that dismantle and thwart malign operations—while maintaining transparency, accountability, and opportunity to review in the process. China will continue to promote narratives of “social harmony” over truth, but there are increasing signs that the backlash may generate the social instability and threat to their governing regime that they fear most.

Pluralism vs. Homogeneity

America has the Statue of Liberty; China has the Great Wall.

The United States and China are deeply characterized and influenced by America’s pluralistic, “nation of immigrants” society and China’s near-homogenous one. In the US, 45.3 million Americans living within its borders today were born in another country. That comes out to nearly one of every seven people living in the United States being born abroad. Just one of every 1,000 Chinese is an immigrant.

The implications of these differences are far-reaching in the AI competition for recruiting the world’s top generative AI research talent—where the United States is far ahead of China. Nearly 4 of 10 Silicon Valley residents are foreign born, and half of Silicon Valley startups named at least one immigrant as a founder. Not surprisingly, the US had 57% of the US global total of AI researchers compared to China’s 12%.8

Historically, the United States has successfully caused “brain drain” all over the world due to the attractiveness of our social, economic and political freedoms—from protecting individual privacy, freedom of expression, civil rights, and worker and consumer protections, to the ability to secure patents and profits from the ideas one creates. Even as China has increased its domestic tech talent, they are experiencing a negative brain drain of its own in the tech industry with talent seeking to live in a democratic system, citing China’s negative social and political environment.9 Despite the PRC boasting the largest proportion of top-tier AI researchers at 29%, over half of those researchers go on to live and work in the United States.

America has aspired to be a pluralistic and diverse country, generally accepting of immigrants—with notable periods of exception. China is 92% Han Chinese, has not and does not value immigration, and is overtly hostile to ethnic minorities within its borders as a matter of state policy. Muslim Uyghurs to Tibetan Buddhists have long-been subject to cultural genocide and forced assimilation. Whether it be state-endorsed oppression of ethnic, religious, or LGBT minorities, the advancement of Chinese AI regulations have not been slowed down by the civil rights-related concerns the US continues to grapple with. To the contrary, China’s AI development in facial recognition technology has been fueled in large part by the PRC’s desire to more effectively track and racially profile minority groups.

Immigration has never been an easy road for America, but it will always be a black hole for China. 4 million people visit the Statue of Liberty each year. One million green cards are issued annually. Thousands risk their lives on a daily basis trying to enter America to get a shot at the American Dream. We also gave birth to the racist and anti-immigrant Ku Klux Klan, passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, and are roiled by immigration politics to this day.

The 10 million tourists who visit the Great Wall each year marvel at an architecture structure set upon a magnificent landscape, but they also see a working symbol of China’s insular nature. No one is breaking down the door to get into China, except North Koreans. And after Mexico, China ranks second among émigré countries to the US. There is no scenario in which the US beats China in the AI race without functioning high-tech visa and immigration policies. During this period of xenophobia and isolationism, America must not forget that our clearest advantage over China in the AI race comes from the people who choose to live here.

Beacon of Democracy vs. The Middle Kingdom

Both nations share a mythology that places them at the center of world leadership. America is the “beacon of democracy,” the “city on a hill,” the “leader of the free world,” “the reluctant warrior” who “walks softly but with a big stick.” China translates to the “Middle Kingdom” at its most literal—the core, central part of the world that other nations revolve around. The race for global AI supremacy will depend on each nation’s strength in global leadership, but also which style and approach will prove the most successful and attractive in the 21st century.

After World War II, the US became the clear diplomatic leader in multilateral institutions including the United Nations, NATO, and G20, among other others. They are all designed to promote global peace and prosperity. The US helped develop the concept and structure for a rules-based international order, where spreading democratic values, promoting human rights, and increasing economic mobility was meant to triumph over military conflict and coercion by illiberal states. In this new world order, American leadership has long-provided a competitive edge through building diverse foreign coalitions to share information and develop global rules of the road that reflect America’s shared interests with western-style democracies.

This world order is under challenge by China which chafes under western rules that does not respect the seat China wants at the table. China views the current domination by democracies in global institutions as contrary to its national interest and intent on thwarting its rise to the world’s top superpower. Part of the Middle Kingdom mythology is the century of humiliation from 1842 to 1949, where China was subjugated often at the hands of Western powers. China had previously been an undisputed top power in the international order throughout thousands of years of history. The related concept “Tianxia” (天下)—literally means under the sky but connotates how all of the world under Heaven—the physical, geophysical space of all nations—is under the political sovereignty of the Middle Kingdom in a hierarchical fashion.

In practice, China under Xi Jinping has been pursuing a rival and replacement of the liberal rules-based order—where multilateral rules and values are subordinate to simple power and coercion. At face value, the PRC’s pitch to other nations resembles late 20th century Chinese foreign policy pillars emphasizing “non-interference in each other’s internal affairs,” along with “peaceful co-existence.” The subtext is that China is offering a version of peace and prosperity without the burdensome expectations of first adopting democratic liberal values or respect for human rights—a standard many nations cannot meet. Ultimately the PRC places Chinese national interest over how a country behaves internally—including oppression or persecution of its minority populations, as China systemically does domestically. This model may prove an advantageous and attractive pitch to leaders who already lean authoritarian, and where AI-powered technologies are especially well-positioned to deepen control over the domestic populations.

In reality, China’s AI global strategy is more complicated than the innocuous pitch of “non-interference” and mutual benefit. China’s far-reaching Belt and Road Initiative has appeared predatory in many instances, with recipients accusing China of “debt-trap diplomacy.” An Associated Press analysis of over a dozen countries most indebted to China found countries with as much as 50% of their foreign loans from China and devoting more than a third of their government revenue to pay China back—draining tax revenues needed to keep electricity on and schools open amidst financial default.

China has leaned into obtaining global influence through a proliferation-first approach of its AI technologies so that other nations are dependent on China. They use this for economic coercion, as China successfully did with mass deployment of cheap telecommunications tech worldwide. More than 140 cities around the world are “smart cities” powered by Chinese, AI-driven surveillance technology. This is despite China’s supposed agreement to endorse international UNESCO standards explicitly barring mass surveillance in AI as a legitimate use.

The US is now attempting to set AI norms and standards through existing international infrastructure but frankly needs to redouble its efforts to catch up on its own AI frameworks to successfully lead the rest of the world. Despite the American opportunity for greater global legitimacy, every day the United States is not leading AI advancement through the rules-based order is a day China is one step closer to the Middle Kingdom by proliferating its own AI technologies and creating economic dependencies in nations across the world.

Conclusion

“China’s digital authoritarianism has been described as ‘one giant QAnon’ and is ubiquitous among the 1.4 billion inhabitants of the country. Moreover, one of the greatest threats to American national security interests is if China prevails in exporting and normalizing its model of digital supremacy.”

We wrote those words in June 2022 for the launch of Third Way’s US-China Digital World Order Initiative, in which we warned that “China is executing a detailed plan to become the world’s digital superpower.” There may be no tech sector where these stakes are higher than in the rapidly developing race of generative AI, where the world is still in the early stages of seeing powerful AI tools transforming our daily experiences.