Report Published April 26, 2017 · 29 minute read

Empowering Equality: 5 Challenges Faced by Women Entrepreneurs

Susan Coleman & Alicia Robb

WHAT’S NEXT?

The number of women-owned firms in the United States has grown dramatically in recent years, and yet they are fewer in number than firms owned by men, they are smaller, and they employ far fewer people. What holds them back? Why are women-owned firms less likely to also be growth-oriented firms?

Susan Coleman and Alicia Robb have been studying these questions for some time now, and they find that to understand the gap between male- and female-owned firms, we need to look at five factors: education, experience, social capital, financial capital, and confidence.

For instance, although women have made enormous strides in education in recent years, such as surpassing men in the number of degrees granted, they are still underrepresented in fields like engineering and computer science, which are the foundations for so much entrepreneurial activity. Similarly, while women have held more and more roles in corporations, Coleman and Robb find that they’ve been less represented in the kinds of positions that “involve senior-level strategic planning and priority setting.”

They also find that women do not tend to have the kinds of robust networks that are so essential to entrepreneurial success. In federal contracting, for instance, the Clinton Administration tried various strategies to increase the number of women contractors, and yet, despite owning more than 30% of all the firms in the United States, it took 15 years for women-owned firms to achieve a target of 5% of all federal contracts! They comment that this is “hardly a ringing endorsement for equal access.” Women are similarly underrepresented in incubator and accelerator programs.

“The dual challenges of experience and networks, both of which we have discussed, ‘spill over’ into the area of financial capital, exacerbating the challenges women entrepreneurs face in that area,” write Coleman and Robb. This results in the fact that women entrepreneurs “…on average, raise smaller amounts of financial capital than men and are more reliant on internal rather than external sources.”

Finally, Coleman and Robb argue that women have lower levels of self-efficacy and confidence than men, and that the paucity of female role models is a big problem for would-be entrepreneurs. While many of the challenges women face are structural in nature, “others come in the form of cultural or attitudinal barriers.”

The paper is a balanced and forward-looking analysis of the challenges facing women entrepreneurs. Any plan for increasing economic growth must focus on the important steps that can be taken to encourage and nurture more entrepreneurship. “Empowering Equality: 5 Challenges Facing Women Entrepreneurs” is the latest in a series of ahead-of-the-curve, groundbreaking pieces published through Third Way’s NEXT initiative. NEXT is made up of in-depth, commissioned academic research papers that look at trends that will shape policy over the coming decades. Each paper dives into one aspect of middle class prosperity—such as education, retirement, achievement, or the safety net. We seek to answer the central domestic policy challenge of the 21st century: how to ensure American middle class prosperity and individual success in an era of ever-intensifying globalization and technological upheaval. And by doing that, we’ll be able to help push the conversation towards a new, more modern understanding of America’s middle class challenges—and spur fresh ideas for a new era.

Jonathan Cowan

President, Third Way

Dr. Elaine C. Kamarck

Resident Scholar, Third Way

***

Introduction

Women have sprinted past men in educational attainment. They are earning more BAs, MAs, and PhDs than men. Why do they remain so far behind in entrepreneurship?

Sure, there’s good news. Women-owned firms have made great strides in recent years. The U.S. Census Bureau estimated that there were 9.9 million women-owned firms in the United States in 2012, representing 36% of all firms, a dramatic increase over 28.7% just five years earlier. In fact, the number of women-owned firms grew by 27% from 2007 to 2012, compared with a growth rate of 2% for firms overall1. These numbers suggest that a growing number of women are choosing entrepreneurship as a career path and as a means for putting their talents, creativity, and initiative to work.

In spite of these impressive statistics, women-owned firms are still in the minority, and there are roughly two male entrepreneurs for every woman entrepreneur in the United States. Similarly, for those women who do pursue the entrepreneurial path, the vast majority launch small rather than growth-oriented firms. The same 2012 U.S. Census data reveal that fewer than 20% of women-owned firms have any employees aside from the entrepreneur herself, and collectively, women employ only 7.5% of all employees. This is an important consideration in an economy that is still feeling the effects of the “Great Recession” and the ensuing focus on job creation.

We all know that women are just as smart, creative, and hard-working as men, so what’s holding them back from becoming entrepreneurs and growing their firms? That question sets the stage for our discussion of the five challenges faced by women entrepreneurs. These challenges fall into categories we have entitled human capital (education and experience), social capital (networks), financial capital (sources of funding), and the need for role models. Some of these challenges, such as education, experience, and sources of funding, are structural in nature, while others, such as networks and the lack of role models, emerge from various stereotypes and expectations. These challenges represent potential roadblocks, but, as we will show, there are ways to get around them as proven by the experience of a growing number of intrepid women entrepreneurs like those we profile in our recently published book, The Next Wave: Financing Women’s Growth-Oriented Firms2.

Challenge #1: Education

Our first challenge, education, is one kind of “human capital” that helps an entrepreneur build her skills and abilities while also preparing her for various tasks or careers. Nobel Prize winner Gary Becker highlighted the importance of education and its impact on earnings in his classic study on human capital first published in 19643. It may surprise you that we have chosen education as a challenge for women, since data indicate that women actually have higher levels of educational attainment than men. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, women were awarded 57.2% of undergraduate college degrees, 60.1% of master’s degrees, and 51.4% of doctorates in 2010-20114. In spite of these educational accomplishments, women and men tend to focus on different fields of study. In particular, men are more likely to have degrees in the STEM fields, which include science, technology, engineering, and math. Data gathered by the National Science Foundation shows that in 2010, 36.6% of all undergraduate degrees awarded to men were in the fields of science and engineering, compared with 27.7% for women5. These fields are important, because they are a source of entrepreneurial initiatives in key industries like computer science, technology, and bioscience.

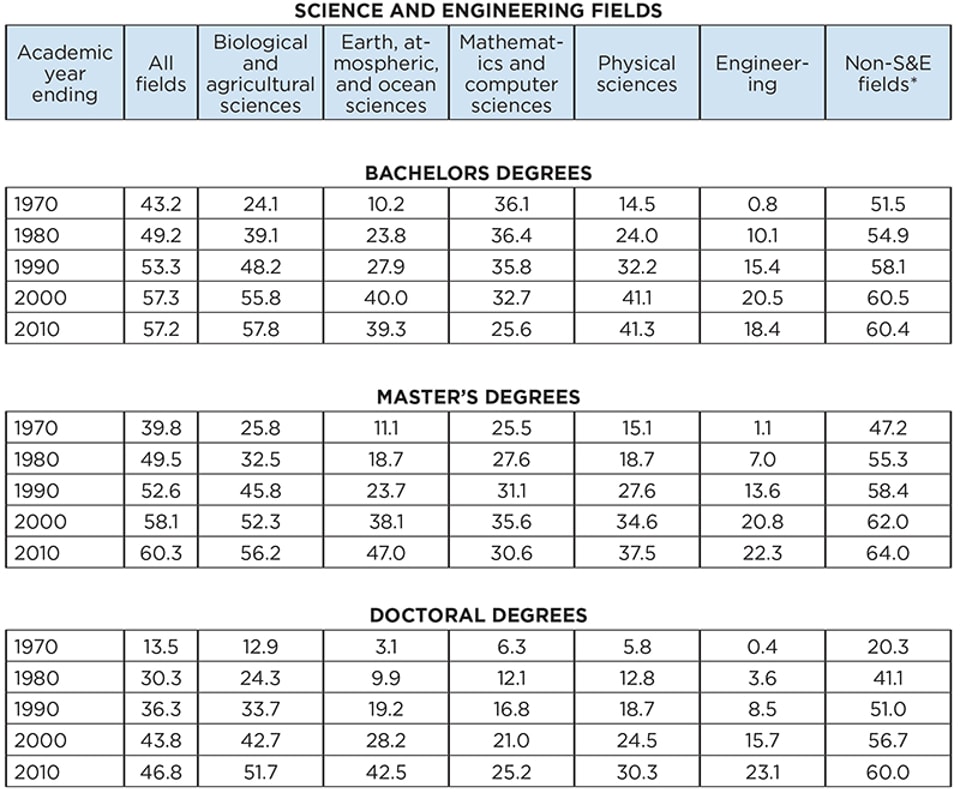

Within the STEM disciplines as well, many of the sub-fields, including mathematics, computer science, and engineering, continue to be dominated by men, and studies reveal that women who venture into them often face environments that are unwelcoming and even hostile6. Nevertheless, women are making important inroads in STEM at all levels of educational attainment. As Table 1 illustrates, the percentage of doctoral degrees awarded to women in all STEM fields increased from 13.5% in 1970 to 46.8% in 2010.

Table 1: Percentage of Degrees going to Women by Field, United States 2010

SOURCE: Tabulated by National Science Foundation/National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NSF/NCSES); data from Department of Education/National Center for Education Statistics: Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System Completions Survey. * S&E = science and engineering

What has led to the change over time in the types of degree programs women pursue? Many of these gains have come about thanks to educational initiatives focused on attracting girls and young women into the STEM fields at the local, state, and national levels. The National Science Foundation7, in particular, has been instrumental in encouraging and supporting programs designed to attract and engage female students and faculty in the fields of science and engineering. Other initiatives have targeted girls at an even earlier age in an attempt to combat gender stereotypes and raise the level of awareness by young girls of the full range of their educational and career opportunities.

A growing number of technology-based companies have also take steps designed to help them attract and retain more women employees, who currently make up only 30% of their workforce8. Initiatives include expanding parental leave (for both men and women), increasing flexibility in scheduling, establishing diversity goals in hiring, and advancing women to leadership positions. Similarly, firms are taking steps to retain talented women by highlighting potential career paths, creating support networks for women, and moving away from a “brogrammer” company culture9. Eventually, as more women enter the STEM fields, the power structure will change in ways that will enfranchise and empower the girls and women who follow. For now, however, these statistics reveal that we still have work to do in terms of removing the structural and cultural impediments that discourage girls and women from pursuing these fields and the careers that emerge from them.

Challenge #2: Experience

Along with education, previous experience is the other major type of human capital, and it serves as a major building block for entrepreneurial firms. Experience can come in the form of prior work experience in general, experience working in a particular industry, managerial experience, or previous experience in launching an entrepreneurial firm. As in the case of education, women have made impressive gains in the workplace, and the number of women working outside the home has increased dramatically since the World War II. As of 2014, 57% of all U.S women age 16 or older were participating in the workforce, compared to 43.3% in 197010. The percentage of women in the workforce during the prime working years of 25 to 54 was even higher, at 73.9%

Women have also made workplace gains by advancing into managerial roles and are well-represented in the middle-management ranks of most major corporations. In spite of these gains, women are still underrepresented at the most senior management levels. Similarly, women continue to be underrepresented on boards of directors. Thus, although women have acquired a tremendous amount of workplace, industry, and middle-management experience, they have gained less experience in making the types of decisions that involve senior-level strategic planning and priority setting. To illustrate this point, Catalyst, an organization devoted to expanding opportunities for women in business, reported that in 2015, women held only 4.2% of chief executive officer positions and 19.9% of board of director seats for Fortune 500 companies11.

There is some evidence that companies are taking steps to narrow the gender gap, given that Catalyst also found that 26.9% of new board positions were held by women. Similarly, 25.2% of executive/senior level manager positions were held by women, suggesting that a sizeable cohort of women are moving up the corporate ladder and acquiring the types of experience and skills necessary to launch and grow their own firms. Nevertheless, women’s progress toward reaching the top of the corporate pyramid is painfully slow, and significant gender inequities persist.

A recent report published by Leanin.Org in conjunction with McKinsey & Company noted:

“Women are still underrepresented at every level in the corporate pipeline. Many people assume this is because women are leaving companies at higher rates than men or due to difficulties balancing work and family. However, our analysis tells a more complex story: women face greater barriers to advancement and a steeper path to senior leadership.”12

What will it take for women to crack the C-Suite code? A growing number of research studies show that diverse teams lead to better decisions and better outcomes13. Articulating these research findings so that the corporate community really understands this will help to communicate the value of having women, as well as men, in senior management and board of director roles. This heightened understanding can be coupled with sustained efforts on the part of corporate leaders to identify and mentor women employees while also providing them with the types of experiences that will prepare them for executive roles.

Women themselves can play an active role in encouraging firms to hire qualified women and to provide them with career paths leading to senior level positions. According to IRS data, women represented 42.4% of top wealth holders in the United States in 200714. Thus, women are not only customers, but also investors and stockholders. As such, they have the power to influence the companies they buy from and invest in.

Challenge #3: Networks

Like human capital, social capital in the form of networks and key contacts is an essential resource for women entrepreneurs. Social capital refers to the people you know and the groups or organizations you are a part of. The importance of social capital lies in the fact that it serves as a means of helping entrepreneurs secure the resources they need to launch and grow their firms. This is particularly true for growth-oriented entrepreneurs who require substantial resources in the form of people, facilities, and funding. In this sense, social capital is an essential building block for success for growth-oriented entrepreneurs. Similarly, the entrepreneur’s networks and contacts can provide valuable information in addition to emotional and financial and managerial support15. Studies suggest that, although women entrepreneurs have made impressive human capital gains in the areas of education and workplace advancement, they still lag men in terms of developing the types of social capital needed to launch and grow firms that will achieve significant size. Stated simply, women entrepreneurs are less likely to know the “right people” or be a part of networks that would give them access to those individuals16. This challenge manifests itself in a variety of ways, but we would like to focus on just two examples in this article.

The first is in the area of federal contracting. Each year, the United States government spends billions of dollars on federal grants and contracts for products and services that meet its needs and priorities. For 2013, federal grants totaled $503 billion, and contracts totaled an additional $460 billion17. In 2000, during the Clinton administration, Congress passed the Women’s Equity in Contracting Act in response to evidence that women-owned firms did not have equal access to federal contracting opportunities. A final rule for the program was not issued until 2010—10 years later. Subsequently, in 2011, the SBA announced the launch of its Women-Owned Small Business Contract Program to provide greater access to federal contracting opportunities to women-owned firms. That year, a goal of awarding 5% of federal contracts to women-owned firms was established by statute, but not achieved. Two years later, under the National Defense Authorization Act of 2013, the SBA announced changes to the Women-Owned Small Business Federal Contract Program designed to provide further assistance to women-owned small businesses in order to help them secure more federal contracts. Finally, in March of 2016, it was announced that the 5% goal was achieved in 201518. This is certainly a noteworthy achievement and an important step forward. Given that women-owned firms represent more than 30% of all firms in the United States, however, the fact that it took 15 years to achieve a target of 5% is hardly a ringing endorsement for equal access.

Our second example pertains to the participation of women entrepreneurs in incubators and accelerators. Incubators have been in existence for some time, and they typically provide physical space for start-up companies. The majority of incubators are nonprofit entities, and they are often associated with universities, state or municipal governments, or research facilities. Early stage firms are housed within the incubator for a period of time, usually ranging from one to five years. In addition to having a physical space in which to operate, these firms have access to support services in the form of training and industry contacts, and access to professional service providers such as attorneys, accountants, consultants, marketing specialists, angel investors, venture capitalists, and volunteers.

In contrast to incubators, accelerators are a relatively recent phenomenon. The first accelerator was Y Combinator, established in Northern California in 2005. The accelerator model consists of a short-term and highly intensive program, typically lasting for 60 to 90 days, designed to help entrepreneurs bring their product to market and connect with potential funding sources. Entrepreneurs are given a rigorous program of training, mentoring, and technical assistance to help them grow their firms rapidly19. Participants move through the accelerator program as part of a cohort, thereby establishing lasting relationships with members of their group. The selection process is highly selective, with a focus on those firms most likely to succeed and grow in specific industries, such as software design or mobile application development.

In terms of women’s participation in incubator or accelerator programs, prior research suggests that women are even less-well represented than they are in entrepreneurship overall. In their study of more than 18,000 firms that had participated in incubators, Amezcua and McKelvie20 found that only 6% were owned by women. This gender imbalance has prompted some researchers to suggest that, rather than providing a protected and neutral environment, incubators perpetuate the masculine norm for what a successful entrepreneur looks like21. Thus, women participants simply swap a hostile external environment for an equally hostile internal one. Although we were not able to find a gender breakdown for accelerator participants nationwide, given their technology focus, it is very likely that women are in the minority in that environment as well22.

Both of these examples highlight in stark fashion the challenges women entrepreneurs face in gaining access to key networks that could provide them with skills, contacts, and access to economic opportunities. In response, a growing number of scholars and practitioners have called for the need for a women’s entrepreneurial ecosystem to address the unique challenges faced by women entrepreneurs and to help level the playing field in ways that will help not only women but the economy overall23. Although the United States tends to perform well in global studies of women’s entrepreneurship, reports consistently indicate that women are less likely to engage in entrepreneurial activity than men24. Similarly, research that we have conducted ourselves using the Kauffman Firm Survey shows that women are less likely to launch growth-oriented firms, the kind that create a substantial number of jobs25. This persistent gender gap in entrepreneurial activity prompted the Kauffman Foundation’s Lesa Mitchell to write:

With nearly half of the workforce and more than half of our college students now being women, their lag in building high-growth firms has become a major economic deficit. The nation has fewer jobs—and less strength in emerging industries—than it could if women’s entrepreneurship were on par with men’s. Women capable of starting growth companies may well be our greatest under-utilized economic resource.26.

Challenge #4: Financial Capital

A considerable amount of our research has focused on the financing strategies of women entrepreneurs27 and has consistently documented the fact that women, on average, raise smaller amounts of financial capital than men and are more reliant on internal rather than external sources. This is particularly true in the case of the external equity financing provided by venture capitalists and angel investors. Although internal sources of financing in the form of personal savings, funds from family and friends, and personal debt, often in the form of credit cards, may be sufficient for the launch of smaller lifestyle firms, these sources cannot typically furnish sufficient financial capital for growth-oriented firms. Thus, entrepreneurs who aspire to growth have to seek out and acquire external sources of financing, such as bank loans, angel investments, and venture capital.

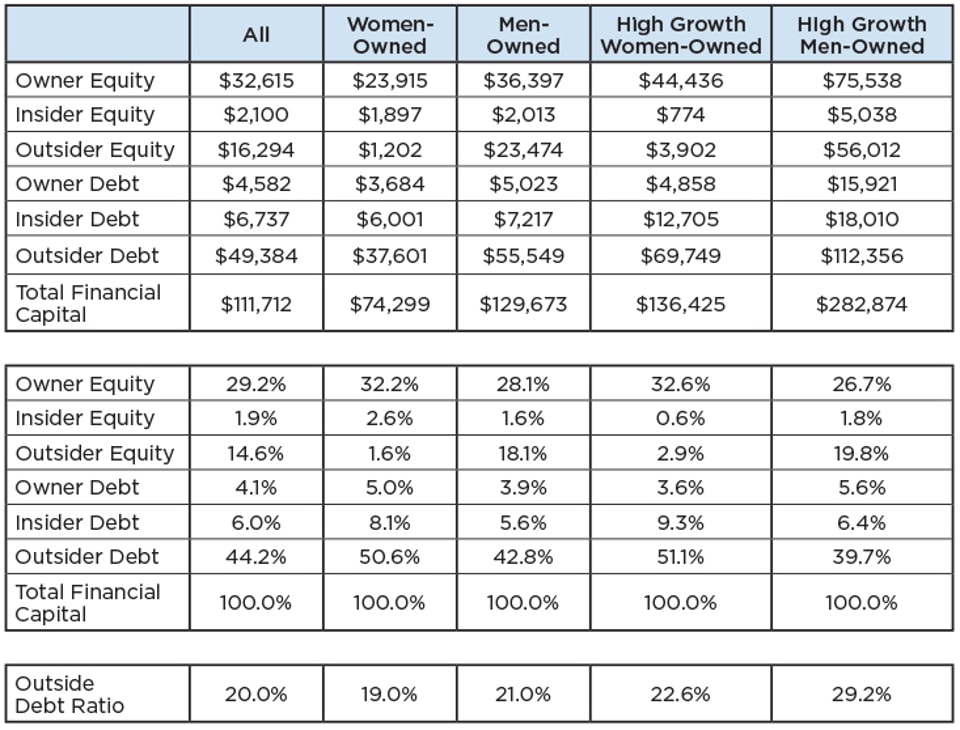

Table 2 provides a breakdown of financing sources by gender for new firms launched in 2004. These data are drawn from the Kauffman Firm Survey, a data set of more than 4,000 U.S firms launched in 2004 and tracked over an 8-year period. Table 2 shows that women started their firms with dramatically smaller amounts of financial capital than men. This was true for all firms as well as for growth-oriented firms. Similarly, women-owned firms were less reliant on both external debt and external equity than men. It is noteworthy that the gender gap in external equity was particularly large for all firms as well as for growth-oriented firms.

Table 2: Startup Capital by Gender (2004)

Source: KFS microdata

What accounts for the funding gap between female and male entrepreneurs? Several theories have been put forth attesting to the effects of gender differences in earnings, networks, and self-efficacy. In essence, the dual challenges of experience and networks, both of which we have discussed, “spill over” into the area of financial capital, exacerbating the challenges women entrepreneurs face in that area. From the standpoint of experience, women earn less than men, are less likely to reach the most senior highly compensated ranks of corporations, and are more likely to experience career interruptions frequently associated with the birth and care of children28. Thus, they have smaller amounts of personal capital that could be used to launch or grow a firm. Our own research using the Kauffman Firm Survey data reveals that although women are heavily reliant on owner-supplied financial capital to launch their firms (32.2%), they actually use less of it in actual dollar amounts than men (Table 2). The gap between the amounts of personal financial capital provided by women versus men launching growth-oriented firms is even larger ($44,436 vs. $75,538). This funding gap in owner equity highlights the importance of creating corporate career paths for women that will allow them to acquire not only senior-level decision-making experience, but higher levels of earnings and accumulated wealth as well.

A second theory, grounded in research conducted by the Diana Project team, is that angel and venture capital networks are heavily male-dominated with few women in decision-making roles29. Thus, it is more difficult for women entrepreneurs to penetrate these networks. Prior research also finds evidence of “homophily” or the tendency of likes to be attracted to likes30. According to this theory, angels and VCs who are primarily male are less likely to give serious consideration to firms launched by women. In response to these findings, a growing number of organizations and programs, including Springboard Enterprises and Astia have emerged to help women entrepreneurs acquire the skills, confidence, and access to networks that they need to raise external capital. Similarly, in response to the need to increase the number of women angels and VCs in decision-making roles, organizations such as Golden Seeds, Illuminate Ventures, Pipeline Angels, and Plum Alley are focusing specifically on funding women-owned firms. Several of these ventures, as well as our own Next Wave Ventures, founded by Alicia, also focus on identifying and developing women with the desire and financial means to become angel investors. These various measures will help us restructure private equity networks in ways that will recognize and value women entrepreneurs and their firms. Similarly, increasing the number of women investors will unharness some of the wealth held by women in the United States and allow those women to take a more active role in how it is invested.

A third theory is that women are more risk averse and have lower levels of “financial self-efficacy” than men31. Self-efficacy refers to the belief that one has the ability and skills to perform certain tasks. This theory contends that, if women are less confident in their financial skills, they will raise less financial capital and be less effective in dealing with providers of financial capital. To illustrate this point, recent research indicates that women entrepreneurs are just as likely to be approved for bank loans as men. Nevertheless, women are still less likely to apply for loans because they fear the will be denied, and when they do apply, they request smaller loan amounts32. How can women build confidence in their ability to deal with financial providers? In our first book, A Rising Tide33, we contend that the best defense is a strong offense. In other words, women who aspire to entrepreneurship need to develop their financial literacy and skills in order to protect their own best interests and those of their firm. There are a variety of ways to do that, including education, training, finding a mentor, becoming part of a network, or creating a management team that includes individuals who have those skills. If we are to increase the number of women entrepreneurs as well as the number of women who want to grow their firms, an entrepreneurial ecosystem that provides these types of opportunities is essential.

Challenge #5: Role Models, Mentors, the Media, and the Message

We don’t have to look very far to find evidence of the gendered nature of entrepreneurship in the United States. Who are our entrepreneurial role models and icons of entrepreneurial success? Several names, all male, come to mind including Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Larry Ellison, Elon Musk; shall we go on? In contrast, successful women entrepreneurs are much less visible, particularly in the types of male-dominated high-tech fields that the media tends to focus on. This focus on male entrepreneurs and male-dominated industries perpetuates the notion that entrepreneurship is not a viable career option for women or that women are not “good at” being entrepreneurs. One of us (Susan) has been teaching entrepreneurial finance for years using case studies. When she started, it was virtually impossible to find case studies featuring women entrepreneurs. What kind of message does it send to women students when 10 case studies featuring 10 male entrepreneurs are taught over the course of a semester? Fortunately, more recent case studies feature greater diversity, although male entrepreneurs or all male entrepreneurial teams still predominate.

Why are role models so important? To answer this question we need to draw upon our earlier discussion of “self-efficacy” which refers to one’s belief that she has the skills and abilities to perform a given task34. A number of studies have found that women have lower levels of self-efficacy than men. If women entrepreneurs have less confidence in their abilities, they may be less willing to take the types of risks that accompany launching or growing a firm. One study of teens and MBA students found that differences in entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) emerge at an early age. Results from both groups revealed that females had lower levels of ESE than males and were less likely to consider entrepreneurship as a career path35. Consistent with this theme, a second study found that women had less confidence in their entrepreneurial abilities than men, and were even reluctant to call themselves entrepreneurs36.

In light of these findings, it should not surprise us that women’s beliefs about their own capabilities may be tied to their willingness (or lack thereof) to pursue entrepreneurship as a career option. Research has shown that female students perceived the task of launching a firm to be more difficult, less rewarding, and, thus, less desirable than men37. Further, these types of attitudinal challenges are not unique to the United States. Using Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) data from 17 countries, including the United States, one group of scholars found that women were significantly less likely to believe that they had the skills necessary to launch a firm and had a higher fear of failure38. Similarly, a study involving graduate students from the U.S., India, and Turkey found that both women and men viewed entrepreneurship as a masculine field with the gender stereotypes and biases that such a viewpoint produces39.

One way to tackle the problem of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in women is to provide more role models of successful women entrepreneurs. We find that the problem is not so much that there aren’t any women role models, but rather that the media, for whatever reason, does not devote the same amount of attention to them that it does to men. In our recent book, The Next Wave: Financing Women’s Growth-Oriented Firms, we highlight three highly successful growth-oriented women entrepreneurs: Oprah Winfrey, Tory Burch, and Sarah Blakely (Spanx), each of whom launched firms with annual sales in excess of $1 billion40. We also highlight women entrepreneurs such as Helen Greiner (iRobot), Sue Washer (AGTC), and Manon Cox (Protein Sciences) who have achieved success in fields traditionally dominated by men. In other words, the stories are out there; we just have to do a better job of telling them and making sure that those examples filter down to girls and young women. The good news is that, increasingly, girls and their parents are seeking and demanding role models who highlight the brains, skills, and initiative of women. Think Dora the Explorer, GoldieBlox, and Rey (Star Wars: The Force Awakens). These media-driven role models pave the way for women’s entrepreneurial role models, including those we have mentioned and others, capable of inspiring the next generation of women entrepreneurs.

Another approach for addressing the confidence gap that we espoused in our first book is mentoring. Mentors can be a valuable source of knowledge and contacts. Equally important, mentors can provide moral support and other affective benefits, such as a great sense of self-efficacy and confidence for new entrepreneurs41. In light of these benefits, if you are an aspiring woman entrepreneur, find a mentor or mentors who have launched successful firms and know the ropes. These individuals have experienced the types of stresses, strains, and dark moments that you may also encounter, and they have found ways to get through them. Conversely, if you are a successful woman entrepreneur, pay it forward by mentoring those who are inspired by your example. No one knows entrepreneurship from the inside out like you do, and you have valuable lessons to share with those who are following in your footsteps.

Closing Thoughts

We love talking to and talking about women entrepreneurs because they represent what we refer to as a “story of happy beginnings.” The good news is that women-owned firms are increasing in both number and economic impact, which has made a lot of folks (including us) sit up and take notice. In spite of that, however, a fairly considerable body of research, as well as anecdotal data, suggest that women continue to face disproportionate challenges when they attempt to launch or grow their firms. As we have noted, some of those challenges, such as women’s lack of senior management experience and the male-dominated nature of the venture capital industry, are structural in nature, while others come in the form of cultural or attitudinal barriers. Whatever the source, collectively these challenges act as impediments to our nation’s economic well-being. If women are discouraged from pursuing an entrepreneurial path, they are less likely to produce innovative products and services, jobs, and wealth for themselves and others. In light of that, our task is not only to identify these challenges but also to design strategies for minimizing or eliminating them.

In his landmark article, “How to Start an Entrepreneurial Revolution” Harvard’s Daniel Isenberg lays out the components of a strong entrepreneurial ecosystem, noting that when these various elements work together, they have the potential to “turbocharge venture creation and growth”42. Significantly, Isenberg positions public leaders and governments at the top of his list. He notes that public leaders need to advocate for and “open their doors to entrepreneurs,” while governments need to create effective institutions to promote entrepreneurs and remove structural barriers43. Other scholars caution that there is no “one size fits all” approach for developing effective ecosystems and urge leaders and decision-makers to design entrepreneurial ecosystems that do a better job of addressing the constraints faced by women in order to accelerate many of the positive changes that are already underway44. We add our voice to theirs. Although we have made great strides in women’s entrepreneurship in recent years, our work is not yet done. Nevertheless, we see The Next Wave as a celebration of what determined women entrepreneurs can achieve. They are “the next wave,” and we can all learn from their example, experience, and success.

About the Authors

Dr. Susan Coleman is the Ansley Chair of Finance at the University of Hartford’s Barney School of Business, teaching courses in entrepreneurial and corporate finance at the undergraduate and graduate levels. A widely published scholar, Coleman is frequently quoted in the business press, and her work has been cited in hundreds of peer-reviewed journals, books, and presentations.

The success of her co-authored book A Rising Tide: Financing Strategies for Women-Owned Firms (Stanford University Press, 2012) led to a follow-up book, The Next Wave: Financing Women’s Growth-Oriented Firms (2016) which examines the experience of women entrepreneurs in high-growth sectors. Coleman is also the co-author of a book on social entrepreneurship titled Creating the Social Venture (Routledge, 2016). Dr. Coleman’s most current research, with co-author Alicia Robb, involves identifying strategies for increasing the number of women angel investors in the United States and abroad.

Dr. Alicia Robb is a Senior Fellow with the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. She is the Founder and CEO of Next Wave Ventures, which has launched two angel funds and training programs in the United States and Europe that are focused on bringing more women into angel investing. She is also a Visiting Scholar with the University of California in Berkeley and the University of Colorado at Boulder. She is the Founder and past Executive Director and Board Chair of the Foundation for Sustainable Development, an international development organization working in Latin America, Africa, and India. (www.fsdinternational.org). Dr. Robb received her M.S. and Ph.D. in Economics from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has previously worked with the Office of Economic Research in the Small Business Administration and the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. She is also a prolific author on the topic of entrepreneurship. In addition to numerous journal articles and book chapters, she is the co-author of Race and Entrepreneurial Success published by MIT Press and A Rising Tide: Financing Strategies for Women-Owned Businesses and The Next Wave by Stanford University Press. She serves on the Board of the National Advisory Council for Minority Business Enterprise, the Advisory Board for Global Entrepreneurship Week, the Deming Center Venture Fund, and is a guest contributor to outlets such as Huffington Post and Forbes.