Report Published January 14, 2022 · 24 minute read

Five Inequities in Health Care

Ladan Ahmadi & Kylie Murdock

Takeaways

Much has been written about cost and coverage issues in the American health care system, particularly since the onset of the pandemic. But there needs to be an equally loud clarion call to address massive inequities in health care. These disparities are unfortunately not a new phenomenon, but little progress has been made toward reaching a more equitable and just system. In this report, we analyze inequity throughout the health care system, breaking down the central issues into five core areas: access to care, cost of care, health outcomes, social factors, and the impact of COVID-19. Understanding these inequities is imperative to reforming health care so it provides the best possible care to all people.

In November of 2020, while wildfire smoke still coated the air of California’s agriculture capital, the San Joaquin Valley, Hardeep Singh got a text that his 63-year-old mother had tested positive for COVID-19.1 She was a line worker in a poultry packaging plant where more than 400 employees tested positive. They were among the many essential workers who had to keep working during the pandemic and, as a result, saw an increased risk of contracting COVID. Agricultural workers like Ms. Singh were especially susceptible because they have a higher prevalence of chronic conditions.2 They also experienced a number of other factors that exacerbated their health situation, including food insecurity, lack of access to health care, and exposure to wildfire smoke and water pollution. Like many other low-income service workers, Ms. Singh struggled with the decision to seek medical care or go back to work. She didn’t have paid sick leave or health insurance, and like many immigrant workers in the Valley, she didn’t speak English. Living paycheck to paycheck, she wasn’t sure if she’d be able to take time off work to quarantine and recover.

Twenty-one hundred miles away, in Chicago, Audrey LaBranche was pregnant with her fifth child.3 She ran a successful child care center in the city and had a side career as a singer. She also had thyroid disease and a history of blood clots and difficult pregnancies. She experienced significant discomfort during her fifth pregnancy, but the birth seemed to go smoothly. A couple days later, she complained of a headache and problems with her C-section incision. Her doctors chalked it up to sinus issues. When her headache continued to worsen, she was rushed to a hospital where she died from a massive brain hemorrhage, a common cause of postpartum deaths.4 If her doctors had further investigated her complaints, her death could’ve been avoided.

Ms. Singh and Ms. LaBranche are just two examples of the health disparities that people of color experience in this country. Ms. Singh lacked health insurance and affordable care options, had a language barrier, worked a job that increased her chances of contracting COVID, and lived in a poverty- and pollution-stricken community. Ms. LaBranche had a history of chronic health conditions and experienced structural racism within the health care system when seeking care after giving birth. In this report, we go beyond these two examples and look at inequities throughout the health care system in America. Specifically, we focus on five central inequities: access to care, cost of care, health outcomes, social factors, and the impact of communicable diseases like COVID.

#1: Access to Care

Many people of color and lower-income individuals in this country struggle to access health care services. For some, lack of insurance holds them back. Others may not physically be able to get to an appointment. We’ll explore three contributing factors:

Inadequate or No Health Insurance

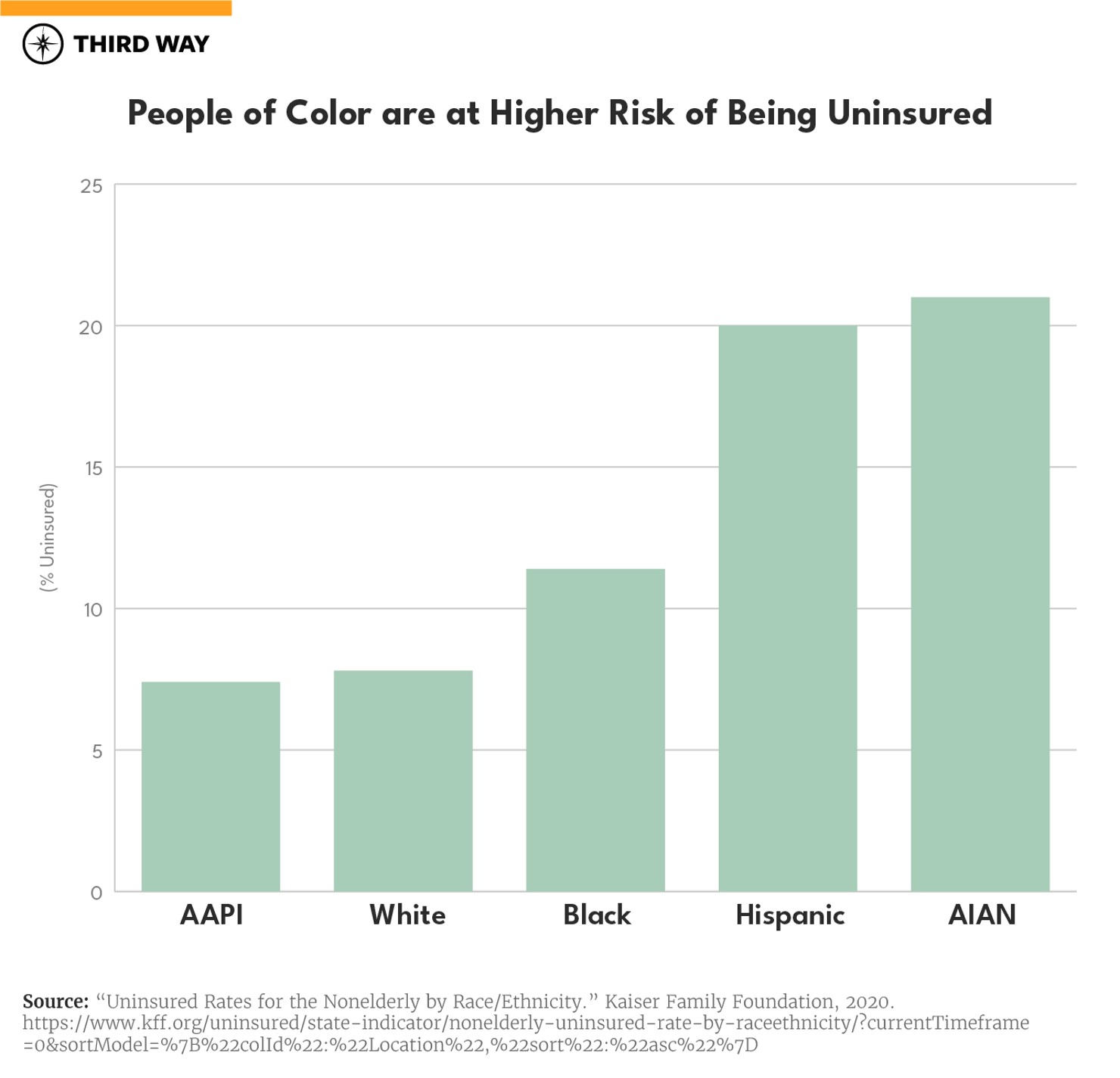

While 89% of people in the United States have health insurance, there are still about 29 million uninsured.5 And nearly 80 million have insurance, but it’s inadequate—their health insurance doesn’t provide financial protection from catastrophic health care expenses.6 People of color are at a much higher risk of being uninsured or underinsured compared to their white counterparts, with Hispanic and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) people at the highest risk of lacking coverage. In 2019, 7.8% of White people were uninsured compared to 11.4% of Black people, 20% of Hispanic people, 7.4% of Asian/Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander people, and 21% of AIAN people.7 Hispanic people accounted for over half (57%) of the increase in uninsured individuals in 2019, representing over 612,000 individuals. And among these uninsured Hispanic individuals, more than a third (35%) were children.

Thanks to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), more people are insured. But that uptake has not been equal across all communities. ACA subsidies are less likely to cover people of color than their white counterparts, and people of color are less likely to live in states that have expanded Medicaid under ACA.8 In the states that haven’t expanded Medicaid, Black people are more likely than white people to fall in the coverage gap—they make too much money to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to qualify for health insurance subsidies through the ACA. Uninsured Hispanic and Asian people are more likely to be ineligible for coverage due to immigration status.9 This was the case with disenfranchised communities in the San Joaquin Valley who are mostly immigrants without legal status and jobs that did not provide adequate health coverage to their employees. In fact, many who became ill with COVID-19 continued to work and handle produce, spreading the disease to their colleagues.10 They didn’t have health insurance and feared they would lose their jobs.

Studies have shown that those who lack health insurance coverage are less likely to seek out medical care, specifically preventative care for chronic illnesses like diabetes, cancer, asthma, and cardiovascular disease, which have higher rates in minority communities. Thirty percent of adults without coverage said that they went without needed care in the past year because of cost, compared to 5.3% of adults with private coverage and 9.5% of adults with public coverage.11 And many uninsured people do not obtain the treatments they need because of the cost of care. In 2019, uninsured adults were more than three times as likely as adults with private coverage to say that they delayed filling or didn’t get a needed prescription drug due to cost (19.8% vs. 6.0%).

For many, not seeing a doctor at the onset of illness or delaying necessary prescriptions means that their next interaction with the health care system will be when they have a more severe illness, resulting in higher costs and less optimistic outcomes. But if the choice is between losing your job, getting hit with an expensive bill—or just hoping you recover without seeing a doctor—many roll the dice.

Transportation and Language Barriers

Transportation and language barriers are also holding people back from accessing care. People of color are less likely to own a car, which causes them to rely on public transportation to reach medical care.12 And public transit is often inadequate and unreliable, resulting in long commutes and unpredictable challenges. This problem tends to be even more pronounced in rural areas where the nearest doctor’s office or medical facility can be hours away. On average, rural Americans live twice as far from a hospital as urban Americans—about 10.5 miles versus 4.4 miles.13 This commute can be harrowing, especially for residents without cars.14 For those who can’t take time off work, going in for a yearly checkup may not seem worth it. And many in these same communities who regularly need prescription medications, transportation can be a huge barrier, especially if they live in an area without a pharmacy.

Language barriers also hold people back from seeking health care, particularly for many immigrant communities. This was an issue for Ms. Singh and other agricultural workers in the San Joaquin Valley as most didn’t speak English. In fact, 67 million US residents speak a foreign language at home and nearly 26 million don’t speak English well or at all.15 People who are deaf and hard-of-hearing also struggle to access care.16 It’s nearly impossible to navigate our already convoluted health care system when you can’t communicate with your doctor.

Limited Health Care Resources

Many minority and low-income communities are more likely to have underfunded medical facilities and fewer resources and doctors.17 Hospitals and doctors avoid low-income communities because residents tend to be uninsured and unable to pay large bills.18 Often, people of color must rely on public or non-profit hospitals that have far fewer resources and worse outcomes. Rural communities experience similar issues: hospitals are far, resources are scarce, and capacity is small.

Public hospitals, community clinics, health centers, and local providers that serve underserved communities provide a crucial health care safety net for uninsured people. However, safety net providers have limited resources and service capacity, and not all uninsured people have geographic access to a safety net provider.19 High uninsured rates also contribute to rural hospital closures, leaving individuals living in rural areas at an even greater disadvantage to accessing care.20 Lack of access to these facilities can cause many adverse health issues. It’s also taken a toll on clinical trial diversity, particularly for new treatments where patients skew heavily white, in some cases, 80% or higher.21

Many of these issues have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic due to overcrowding and excess strain on the system. For example, there has been a dramatic decrease in access to necessary cancer screenings and care. Preventative cancer screenings plummeted by as much as 94% during the first four months of 2020, and the National Cancer Institute predicted almost 10,000 excess deaths over the next decade because of pandemic-related delays in diagnosing and treating breast cancer and colorectal cancer alone.22This will likely have a disproportionate impact on people of color for whom cancer screening rates are the lowest.

#2: Cost of Care

The high cost of health care is one of the leading reasons why people don’t seek out medical care. Insurance premiums and deductibles are often high and lab tests could run hundreds of dollars. We’ll explore two contributing factors of high health care costs:

High Out-Of-Pocket Costs

The high cost of care continues to be one of the biggest roadblocks to health equity. Insurance premiums and deductibles are often high, and health care products and services are expensive. In 2020, the average worker paid $5,588 for family health insurance coverage—not including actual medical costs.23 Depending on one’s plan, deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums can range from the thousands to the tens of thousands. And out-of-network services are even more costly and confusing for the patient. We detail in another report how our current health care system—which pays out doctors, hospitals, and other providers for every service they provide—hurts patients and drives up costs. Patients are charged for every band aid, IV push, aspirin, blood test, and scan, and there are no incentives for providing good outcomes. For example, Claire Lang-Ree, a college student in Colorado, received an itemized bill for her hospital stay. It ran her almost $10,000 for a CT scan, $722 for an IV push, over $6,100 for her ER stay, over $700 for lab tests, $6.50 for aspirin, and more.24 Since people of color are more likely to work lower-wage jobs, not receive health insurance through their employer, and not be eligible for ACA subsidies or Medicaid in their state, they are disproportionately impacted by the high cost of care.

Even under the ACA, many uninsured people cite the high cost of insurance as the main reason they lack coverage. In 2019, 73.7% of uninsured adults said that they were uninsured because the cost of coverage was too high.25 Cost of care can also be a deterrent from seeking medical care in the first place: nearly one in four Americans said they’ve avoided medical care due to the price.26 Most recently, this issue was common during COVID-19—during the first couple months the vaccine was widely available, about a third of people didn’t get vaccinated because they feared being charged for it.27

High out-of-pocket costs have also resulted in a medical debt crisis, especially for people of color. Two-thirds said a major health event in their household would bankrupt them.28 Forty percent of people of color said they would need to borrow money to pay a medical expense that cost more than $500.29 Black Americans were 2.6 times more likely to go into debt for their medical bills.30

Black Americans were 2.6 times more likely to go into debt for their medical bills.

High Cost to Treat Chronic Conditions

Almost 52% of Americans suffer from at least one chronic illness, and people of color are disproportionately affected.31 People of color are less likely to receive preventative services or go to routine appointments, often leaving chronic illnesses undiagnosed and untreated, resulting in worse health outcomes.32 People of color have higher rates of diabetes, obesity, stroke, heart disease, and cancer than white people.33 The risk of being diagnosed with diabetes is 77% higher for Black Americans and 66% higher for Hispanics than for whites. Living with a chronic illness means regular doctor’s appointments, tests, treatments, and medications, all of which can be very expensive. Chronic diseases account for nearly 75% of health care spending in the United States, which stands at $2 trillion.34 People with chronic illnesses will pay, on average, $6,032 a year for health care, and one hospital stay could cost them upwards of $6,000.35 Chronic illnesses sometimes require medication, which can be quite expensive, with one month of insulin potentially costing as much as $332.36

Aside from these costs, studies have found that the onset of a chronic disease reduces wages by 18%.37 Additionally, many chronic illnesses can make it difficult for people to maintain a job at all, particularly in communities of color where people are more likely to work low-wage and physically-taxing jobs. Agricultural workers in the San Joaquin Valley are on their feet all day, sometimes in 100+ degree heat. So not only could a chronic illness serve as a medical detriment, but it can also keep people from working up the socio-economic ladder.

#3: Health Outcomes

People of color often get less, and worse, care for their health conditions. The result? Higher rates of infant and maternal mortality, more chronic conditions, and increased physical and mental health issues.38 We investigate three contributing factors that help explain why:

Insufficient Data

One barrier to health equity is an overall lack of information. Data on health and health outcomes often lacks demographic data—race, age, ethnicity, gender—making it hard to measure the scale of inequities in health care.39 Yet, there are important questions that need to be answered from who is affected to how they are affected. There is also no national standard for what data should be collected, how it should be collected, and to whom it should be reported.40 Currently, states report some data on a mostly voluntary basis, meaning there are many gaps in data and an incomplete picture of our inequity problem. This contributes to a lack of understanding of specific health issues that affect certain populations and the development of policy solutions to treat them.

This lack of demographic data also results in a lack of accountability for medical providers. Studies have shown that people of color receive lower-quality medical care.41 But without more health data showing these inequities, it’s hard to hold providers accountable for providing subpar care, and providers do not have incentives to improve outcomes equitably. For example, nonprofit hospitals receive tax exemptions to provide free health care to financially disadvantaged patients. Without comprehensive data, we don’t know if each of these hospitals are fulfilling their responsibilities and providing quality care—and more often than not, they aren’t.42

Medical Racism

People of color, especially Black people, often experience implicit and explicit racism when seeking medical care. This results in underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis, which can exacerbate chronic illnesses and even death. Studies have found that Black patients are consistently undertreated for pain relative to white patients.43 And people of color are significantly less likely than white patients to receive services and treatments, from pap smears and lab tests to life-saving surgeries.44 This continues to be a pervasive problem throughout the health care system because medical students are taught that Black bodies are physically different, and this is used to justify differences in testing and mistreatment.45 A 2016 survey published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that half of white medical students endorsed at least one myth about physiological differences between Black and white people, including that Black people’s nerve endings are less sensitive.46 There are too many stories of Black patients being prematurely sent home from the hospital despite their concerns and dying as a result.47

A 2020 poll found that seven out of ten Black Americans said they were treated unfairly by the health care system, and 55% said they distrust it.

Medical racism is also a deterrent to seeking out medical care. A 2020 poll found that seven out of ten Black Americans said they were treated unfairly by the health care system, and 55% said they distrust it.48 This discrimination and justified distrust make people of color less likely to seek out and receive medical care.

One result of this is that there is a maternal health crisis in this country. Black women are 3-4 times more likely to die during childbirth than white women.49 Several factors contribute to the problem: lack of access to prenatal and preventative care, social determinants such as pollution and poverty, and chronic illnesses. But the main factor is medical racism. Black women receive subpar care, and their pain is often dismissed.50 For example, after giving birth, Audrey LeBranche, whose story we told at the top, explained her headache and pain to her doctors, but they brushed it off. And like too many other Black women, she died as a result. Women of color also experience more postpartum complications. They are several times more likely to suffer from postpartum mental illness due to a number of factors such as socioeconomic status, lack of social support, and chronic illness incidence.51 And although they have higher rates of postpartum depression, they are less likely to receive treatment. This can be attributed to implicit and explicit racism, stigmatization of mental health, and underdiagnosis. Screening tools for mental health were developed based on mostly white research participants, so they often don’t work when diagnosing women of color.52 Different cultures talk about mental illness in different ways, so physicians often miss the signs of mental illness in women of color.

Lack of Workforce Diversity

Health outcomes are also negatively impacted by the lack of diverse and culturally-sensitive health professionals. The majority of physicians are white—only 11% of doctors are Black or Hispanic despite accounting for over 30% of the United States population.53 Increasing workforce diversity would help to address the widespread issues of medical racism and implicit bias in our health care system discussed above. A more diverse workforce would mean patients of color could find doctors of color who don’t necessarily have the same implicit and explicit biases some white doctors have. They would likely trust medical professionals more and have better interactions. Studies have shown that people of color see better health outcomes when they are treated by a doctor who looks like them; they feel more comfortable opening up and that their concerns are taken more seriously.54 For Audrey LaBranche, having a Black doctor could have meant taking her medical history more seriously and not brushing off her discomfort.

Further, most health professionals aren’t trained in cultural competence, the ability to effectively deliver health care services that meet the social, cultural, and linguistic needs of the patients they serve.55 People of color are more likely to report that they were treated disrespectfully and that their doctor didn’t understand their background or values.56 This results in lower-quality care and patient dissatisfaction, which can result in worse health outcomes and deter people of color from seeking care, which we saw play out with COVID-19.

#4: Social Factors

Social factors, also referred to as social determinants of health, are the conditions in which people are born, grow up, and live. They include a wide variety of factors from housing to air and water quality, to employment, and more. While there are a number of social determinants, we’ll be focusing on three contributing factors:

Pollution and Environmental Degradation

The quality of air and water in a community can have an outsized and detrimental impact on the health of people residing there. Pollution levels tend to be higher in communities of color, resulting in higher rates of respiratory issues, cancer, and other chronic illnesses. It’s no wonder why:

- Power plants and highways are often built within communities of color. In Pennsylvania alone, 85% of power plants are located in Black communities.57 Power plants and cars release millions of tons of air pollution into these communities every day.

- Drinking water systems that constantly violate the law are 40% more likely to occur in communities of color.58 Flint, Michigan is the most well-known example of this. Due to government neglect, Flint, a majority Black community, was plagued with lead-contaminated water for more than five years, killing some people and making many more sick. Water pollution is also a big issue in agricultural communities like the San Joaquin Valley.

- People of color account for more than 50% of all residents living within five miles of a hazardous waste site.59 Hazardous waste can contaminate drinking water, waterways, and even the air.

Exposure to air and water pollution are definitively linked to higher rates of respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, cancer, developmental issues in children, reproductive issues, and premature death.60

Food Insecurity

An individual’s diet is one of the largest predictors of their health. And yet, many communities of color don’t have access to fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and unprocessed foods.

Supermarket redlining refers to the reluctance of chain supermarkets to build stores in impoverished neighborhoods. This has left many of these neighborhoods in “food deserts” where it is extremely difficult to find and buy affordable, quality fresh food. Low-income communities are more likely to have a handful of dollar stores than a grocery store.61 While dollar stores can provide affordable food, they mainly sell nonperishable items, like frozen and canned goods and highly processed foods. And the rise of these chain dollar stores contributes to the closure of local grocers, making it even more difficult to find fresh food.

This leads to what’s called “food insecurity,” where an individual lacks reliable access to enough affordable, nutritious food, including fruits and vegetables. In 2020, one in five Black people and one in four Black children experienced food insecurity, twice the rate of white households.62 Studies have found a strong connection between food insecurity and chronic illnesses like high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes, depression, and obesity.63

Poverty

Poverty decreases the quality of life and impacts both physical and mental health. Due to centuries of systemic racism and lack of equitable economic opportunities, people of color experience poverty at much higher rates than white people. The San Joaquin Valley, a primarily Latino county, has one of the highest poverty rates in the country. Twenty-one percent of Black people and 17% of Latino people experience poverty compared to the national average of 12%.64

Overall, socioeconomic status is the most powerful predictor of illness and mortality.65 Poverty affects health by limiting access to healthy food, safe shelter, medical care, clean air and water, and adequate utilities. It’s associated with various health issues including shorter life expectancy, higher infant mortality rates, and higher death rates. Studies have found that mental illness, chronic health conditions, and substance use disorders are more prevalent in populations with low incomes.66

#5: Impact of COVID-19

COVID-19 has had an immense impact on our society—tremendous loss of life, massive economic upheaval, isolation, an overloaded health care system. And while it’s affected every American, people of color were disproportionately impacted. We’ll explore three contributing factors:

Infection Rate

The COVID-19 infection rate is 1.1x higher for Black people, 1.7x higher for Native people, and 1.9x higher for Latino people than white people.67 People of color also get sicker from the virus—the hospitalization rate is 2.8x higher for Black and Latino people.68 We saw this disproportionate impact on people of color due to several structural barriers, from occupation to housing to comorbidities.

Women and people of color make up a disparate share of essential workers, from grocery store staff and farm workers to restaurant and health care workers. If they didn’t lose their jobs due to the shutdown of the economy, many were required to go into work every day, possibly exposing themselves to hundreds of people who might be infected with COVID, just like the poultry plant workers in the San Joaquin Valley. And those working in health care—care workers, nurses, hospital staff—are often face-to-face with dozens of COVID patients every day.

People of color may also be exposed to more COVID-positive people where they live. Due to redlining and economic inequality, people of color are more likely to live in densely-packed areas and multigenerational housing situations, which creates a higher risk for spread of communicable diseases like COVID.69

As explained above, due to social determinants like poverty and pollution, people of color are more likely to have chronic illnesses such as diabetes, heart disease, and respiratory diseases. Those who are immunocompromised are at a higher risk of contracting, being hospitalized, and dying from COVID.

Death Rate

Along with higher infection rates among people of color, these communities also saw more COVID deaths. The COVID death rate is 2x higher for Black people, 2.3x higher for Latino people, and 2.4x higher for Native people.70

To this day, we see de-facto segregation where Black neighborhoods aren’t given the same resources as white neighborhoods, further perpetuating the racial wealth gap. This extends to hospitals as well. De-facto hospital segregation refers to the placement of prestigious hospitals in high-income and white communities.71Hospitals in communities of color are often underfunded, understaffed, and lack vital equipment. We saw this during the pandemic where hospitals in communities of color ran out of ventilators and beds. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania found that the most direct link to who ended up dying was where they were hospitalized.72 Black patients were more likely to find themselves in hospitals that had worse outcomes overall. Death rates were also higher among people of color due to comorbidities and medical racism as mentioned earlier.

Mental Health Impact

The pandemic has affected many peoples’ mental health in a myriad of ways—grief for lost family and friends, depression from isolation, hardship from job loss, anxiety, and substance use. But it’s been especially troubling for communities of color.

People of color were more likely to be infected and hospitalized with COVID-19. Studies have shown that following a COVID-19 hospitalization, as many as half of the patients reported symptoms of psychiatric distress such as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder.73 And the mental health impacts are even worse for those with long COVID who will be living with side effects for years. With higher death rates, people of color were more likely to lose a parent, a sibling, a family member, a close friend, or a child. One in three Black Americans lost someone to COVID-19.74 More than 120,000 children lost at least one parent or caregiver during the pandemic, with more than half of those children being Black or Hispanic.75 The loss of a parent can have catastrophic consequences for the development and mental health of children. And with strict protocols in place in hospitals, many weren’t able to be with their loved ones and say goodbye before they passed.

One in three Black Americans lost someone to COVID-19.

People of color were also more likely to lose their jobs and source of income, resulting in higher rates of depression and anxiety from not knowing how they’ll pay rent or where their next meal will come from.76 But they were also more likely to have to continue working in person, often leading to anxiety over getting sick and potentially infecting their family. And for many health care workers, seeing dozens of patients die every day certainly contributed to depression and burnout.

Conclusion

Health care inequities have persisted for decades, and recent studies have shown that despite being aware of them, little progress has been made to reaching a more equitable and just system.77 The five inequities covered above—access to care, cost of care, health outcomes, social factors, and the impact of COVID-19—all disproportionately impact people of color and vulnerable communities. Whether it’s a farm worker in the San Joaquin Valley like Mrs. Singh or a Black expectant mother like Mrs. LaBranche, we need a health care system that provides the best possible care to all people.

Our nation’s health care will not succeed until it offers care and prevention to everyone. A multi-faceted approach is required to address these far-reaching systemic problems, which means we need policy addressing medical racism, poverty, care coverage and costs, pollution, housing, and much more. In future reports, we will dig into some of the solutions more thoroughly.