Report Published February 2, 2024 · 6 minute read

Occupation Bifurcation: How Non-College Work Has Separated

Anthony Colavito

Takeaways

- Over the last 30 years, the work that non-college and college-educated workers do has bifurcated.

- The number of full-time workers in managerial and professional occupations has nearly doubled, but workers without a college degree accounted for just 13% of this gain.

- Non-college workers shifted away from stable jobs that supported a middle-class life to work now at the bottom end of the labor market. From 1992 to 2022, the number of non-college workers in service and transportation jobs surged by 25% to 18 million.

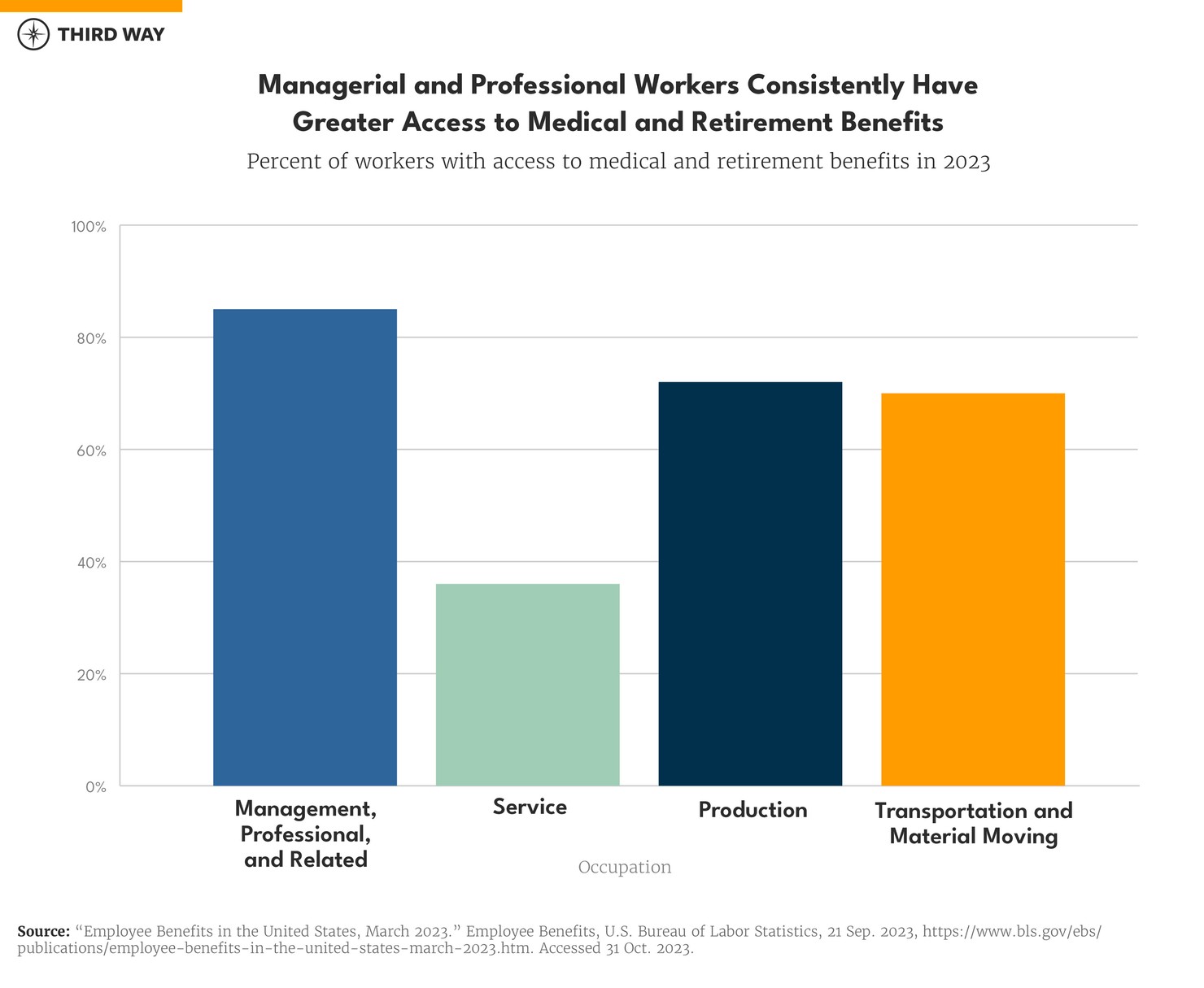

- The gap in pay between these types of jobs is growing. Today, the average hourly wage of professional class jobs is double that of service and transportation jobs. And professional jobs offer better benefits than service and transportation occupations.

The first moving assembly line changed what it meant to build a car. It also allowed Ford Motor Company to sell automobiles at low prices and employ workers at high wages. A century later, new technologies are having equally as profound impacts on society—changing the landscape of American jobs and driving demand for new types of work. Over the past 30 years, the meaning of a good job has been redefined by the rise of the internet, information technology, and automation—just as Ford’s assembly line transformed work one hundred years ago. But as work has changed, career paths for workers bifurcated—further separating those with a degree from those without.

In order to explore how jobs have changed for those without a college degree, we tracked how the occupational mix of the full-time wage and salary workforce changed from 1992 to 2022. Two notable trends emerged. The professional classes—which include workers like engineers, lawyers, and physicians—saw explosive growth, providing opportunity for college grads over their non-college peers. And production and operations work declined, pushing non-college into lower-wage service work. Occupations bifurcated, and workers without 4-year degrees lost out everywhere.

Left Out of the Professional Classes

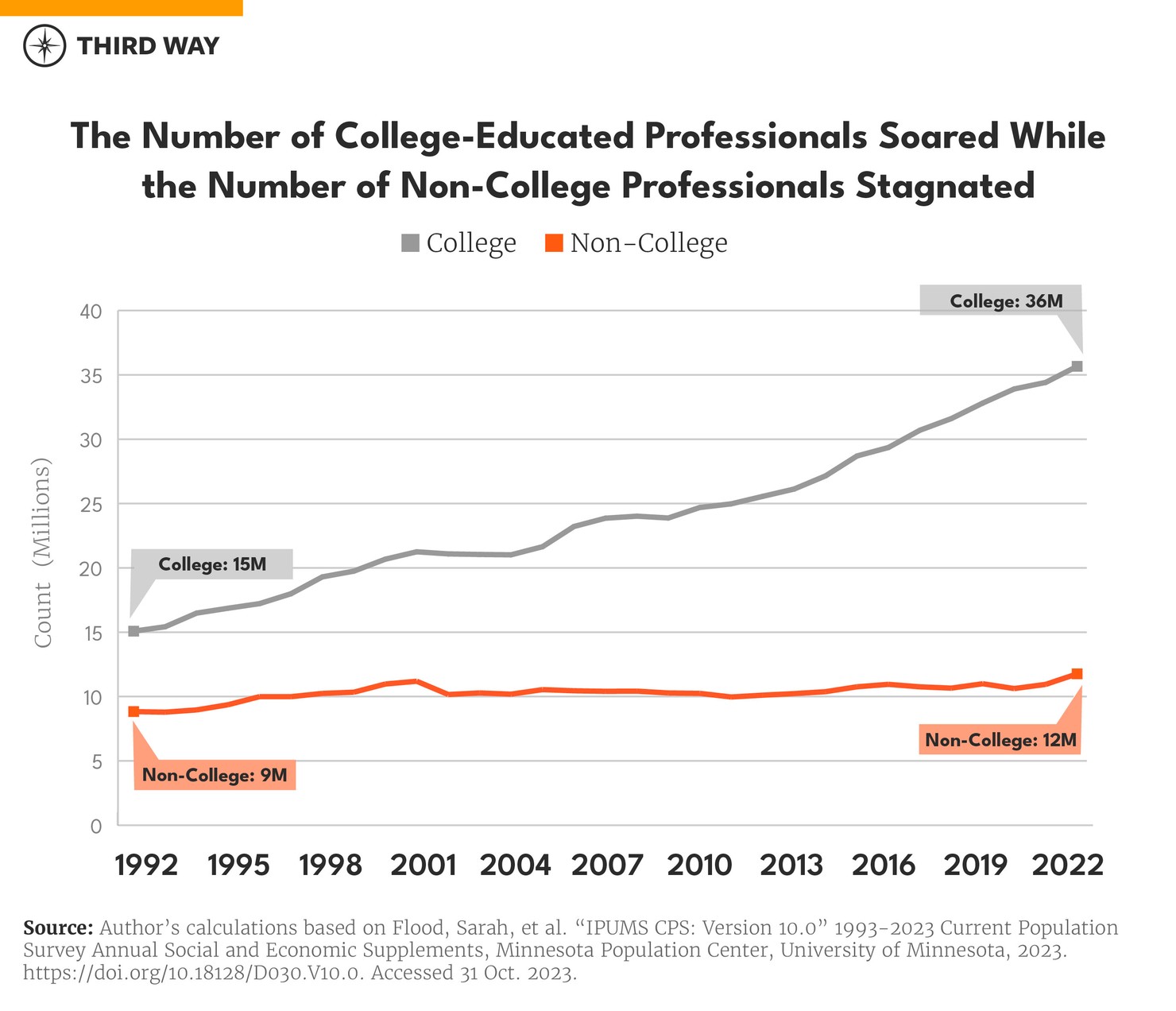

The total number of full-time workers in managerial and professional occupations nearly doubled over a 30-year period, but workers without a college degree accounted for just 13% of this gain. In 1992, 24 million people were in professional occupations. Of that number, 8.8 million didn’t have a college degree. But as the number of workers in these occupations grew to 47 million in 2022, the number of non-college workers in them only grew to 12 million.

These shifts mean non-college workers represent an ever-decreasing share of the professional classes. In 1992, workers without a degree accounted for 37% of managerial and professional workers. But by 2022, their share fell to 25%.1

What’s driving these shifts? New technologies, automation, and global trade fueled demand for more specialized professional jobs.2 Employers now demand workers like computer scientists, software developers, and consultants at higher rates than in the past. And with the rise of remote work, more workers can consult, advise, and provide specialty services from the comfort of their home. But all too often, these jobs require college degrees.3

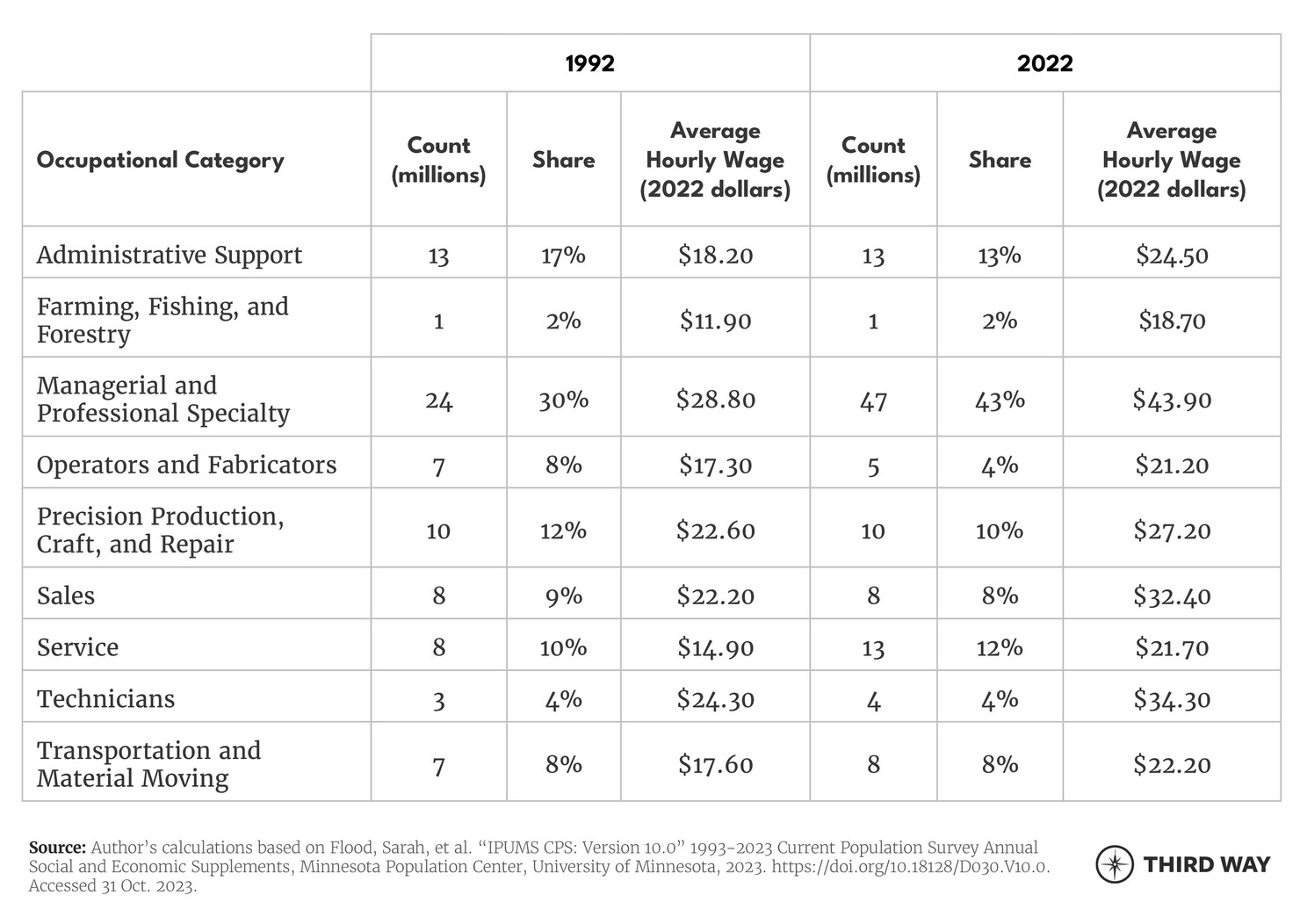

The shift of non-college workers away from the professional classes means they have often failed to benefit from the large wage gains that accompanied these more lucrative jobs. In 1992, the average hourly wage of workers in professional occupations was $28.80 in 2022 dollars, $5 higher than the average wage in the next highest paid group.4 By 2022, that lead widened to $10.5

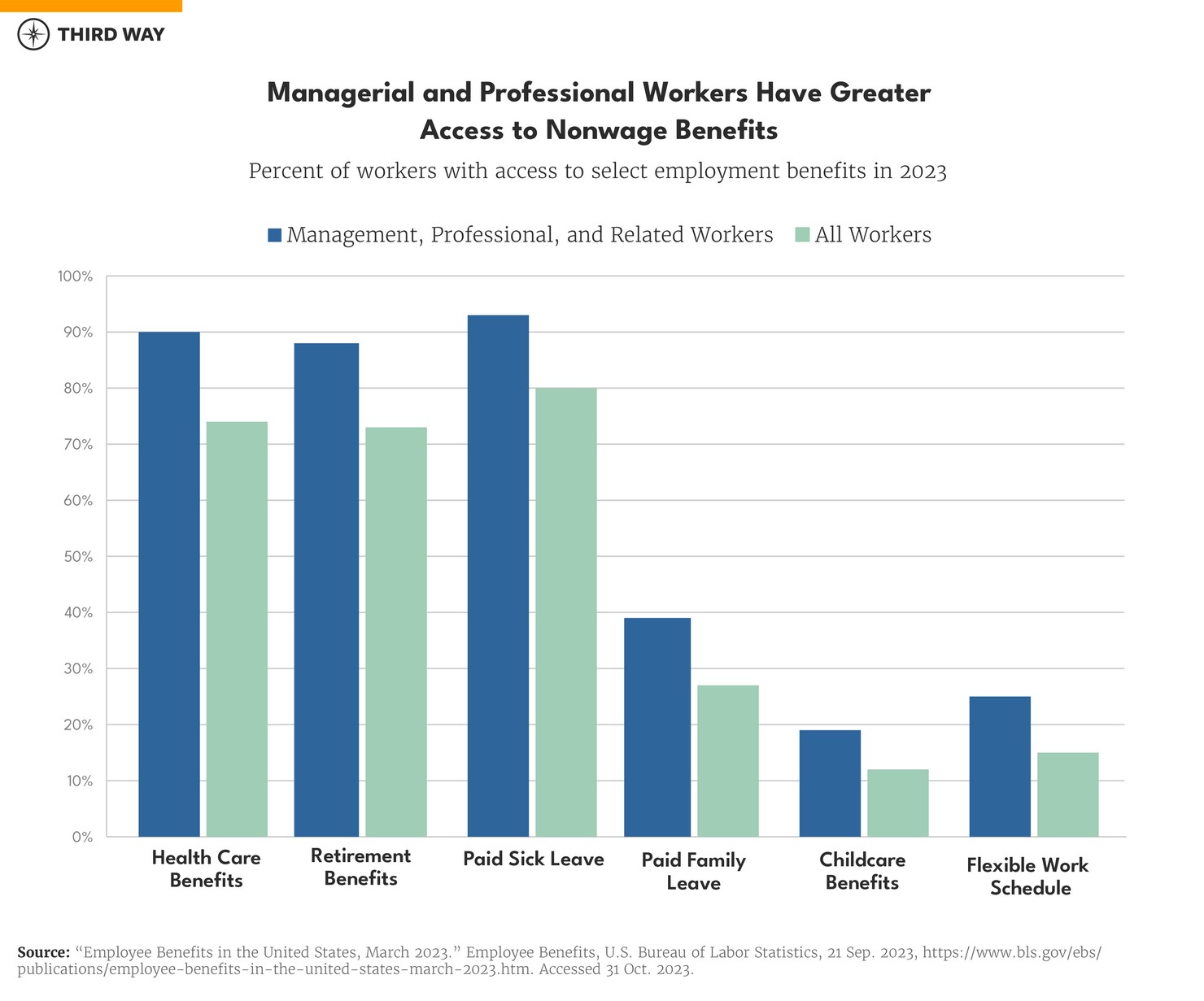

Non-college workers are also increasingly missing out on the noncash benefits of professional jobs. Ninety percent of workers in management, professional, and related occupations have access to health care benefits, 88% have some kind of retirement plan, and 93% have paid sick leave.6 These levels are 13-16 percentage points higher than the average for all workers.7

Serving, Not Making Things

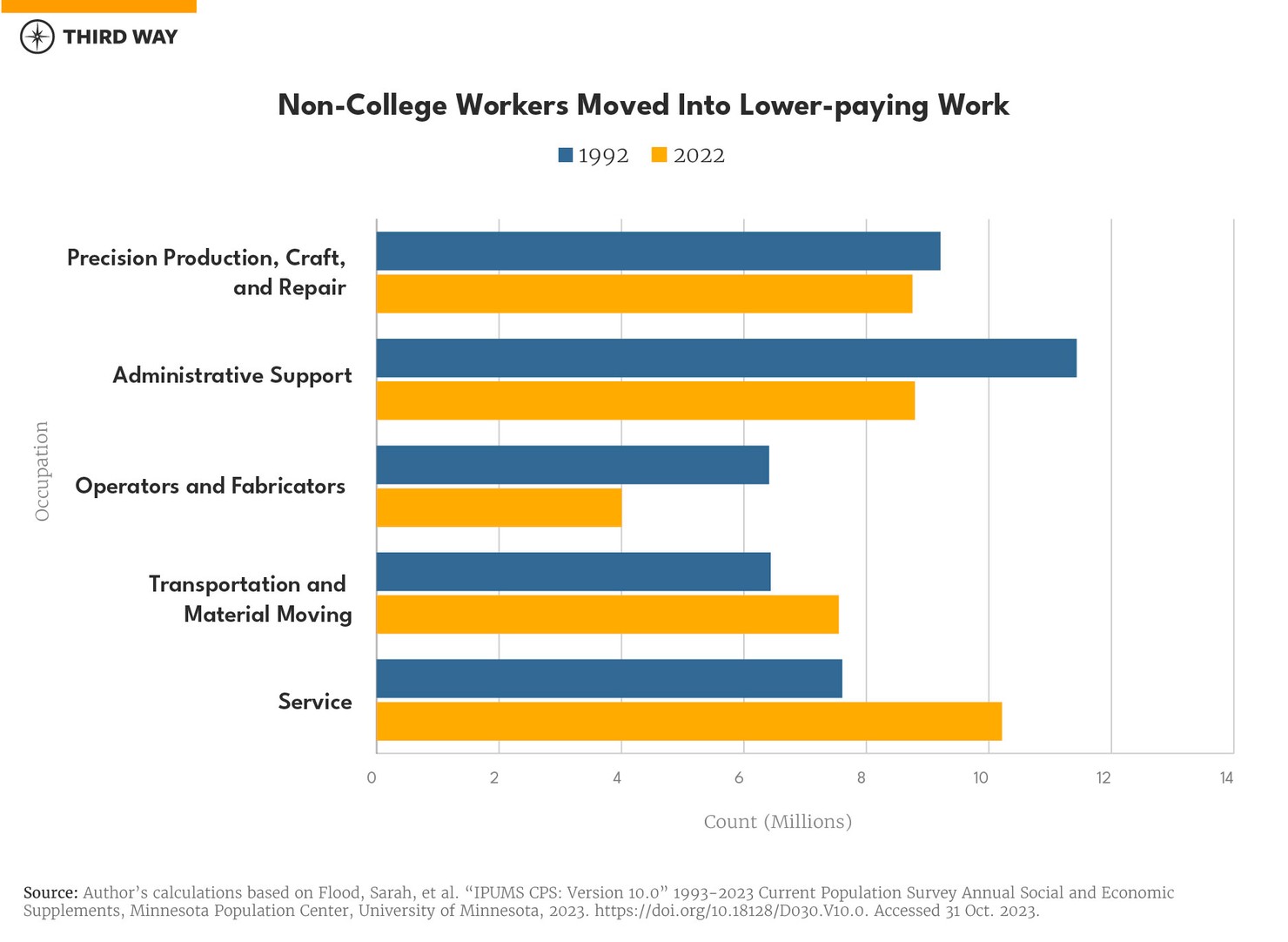

Non-college workers have also seen a shift away from jobs previously viewed as stable and supporting a middle-class life to those now at the bottom end of the labor market. In 1992, there were 27 million non-college workers in production, operative, and clerical occupations—jobs like autoworkers, mechanics, clerks, and office assistants.8 By 2022, there were 21.5 million, a 20% decline.9 Meanwhile, the number of non-college workers in service occupations and transportation surged, rising from 14 million in 1992 to 18 million in 2022, a 25% increase.10 Now, many more non-college workers are working jobs like bartending, nursing aides, and warehousing than 30 years ago.

While service and transportation and material moving occupations experienced wage gains over the 1992-2022 period, their earnings growth was outpaced by those in managerial and professional jobs. The average hourly wage of workers in service occupations and transportation occupations rose by 46% and 26% respectively.11 In comparison, the average hourly wage of managerial and professional workers increased by 52%.12 Now, the hourly wage of professional class jobs is double that of service and transportation jobs.13

On top of that, the average wages in occupations non-college workers are entering are lower than those of the occupations from which they are exiting. For example, the average hourly wage in service occupations is $21.70, about $6 less than the average wage in production occupations.14 These new jobs are also less likely to offer important benefits. Since 2013, only around 40% of service jobs provided medical and retirement benefits.15 In comparison, 72% of production jobs provide them.16 And the types of jobs accruing to the college-educated offer the best benefits of all—85% of managerial and professional jobs offer medical and retirement benefits.17

The combination of non-college workers falling out of middle-pay, good-benefits occupations into low-pay, small-benefit ones mean those without a degree are falling further behind their college-educated peers.

Conclusion

Non-college workers are falling into low-pay work. The college-educated are rising into the professional classes. In light of that, there needs to be a rethinking of what credential is truly necessary to join the professional classes. For example, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro eliminated college degree requirements for most state jobs, and other states have followed suit.18 While these are great first steps, there needs to be a nationwide commitment to rethinking what credentials are needed on the job. And while we open career pathways to all, we must continue searching for ways to make all work pay better. There’s no reason a college degree should be the only key to economic success and a middle-class life.

Appendix

This analysis was conducted using the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) for all years between 1992 and 2022. Our sample was limited to full-time wage and salary workers between the ages of 25 and 64. Occupations were classified using the 1990 Census Bureau occupational classification system and grouped into nine major Census-defined occupational categories. Summary statistics for these occupations are presented in the table below.