Report Published November 20, 2012 · Updated November 20, 2012 · 20 minute read

Reframing the Case for Fixing Social Security and Medicare

Michelle Diggles, Ph.D. & Lanae Erickson

Takeaways

This memo offers 4 insights from our focus groups and recommendations to policymakers:

- Voters see inaction on Social Security and Medicare as far worse than action.

- Voters don’t want these programs reformed, they want them fixed.

- Voters perceive significant waste, fraud, and abuse in Social Security and Medicare.

- Voters see Social Security and Medicare as “earned benefit” programs—not “entitlements.”

Advocates of fixing Social Security and Medicare are engaged in a crucial policy battle, but our latest round of public opinion research reveals that the way most of them are speaking about the issue is making their job much harder than it needs to be. Today, if you listen to most responsible advocates of solutions, they frame the issue in terms of “including entitlement reform in a grand bargain to fix the deficit.” But our research shows that this framework alienates the very voters they need to win over.

Our recent focus groups with Democrats and Independents illustrate that Americans are deeply concerned about Social Security and Medicare, hungry for solutions, and willing to accept changes to the programs if framed consistently with their view of the problem.* And there is a dramatically more effective way to make the case to voters than the current eat-your-peas framework.

Peter Brodnitz of Benenson Strategy Group conducted two sets of two focus groups for Third Way, the first two on Long Island, New York, on August 21, 2012, and the second two in Minneapolis, MN, on August 23, 2012. Participants were self-described Independents or Democrats over 45, with 23 identifying as moderate, 6 as liberal, and 3 as conservative.

We recommend that advocates of solving the programs’ problems frame their plans as “fixing Social Security and Medicare so they are there for today’s and tomorrow’s retirees.” By doing so, they can expose those who oppose action as ones who believe the programs don’t need fixing—a notion that Americans simply don’t believe. And they can implicitly reject a radical overhaul, which Americans don’t want.

Finding #1

Voters see inaction on Social Security and Medicare as far worse than action.

Many on the left have argued that changes to Social Security and Medicare are not necessary for the future solvency of these programs. They believe that the programs are in good shape, assert that they are not driving up deficits, and argue that reformers are part of a right-wing conspiracy to end the social safety net. No one believes it. This view is diametrically opposed to what the majority of the public—including the Democrats and Independents in our research—think is true. Not a single participant thought that doing nothing would be helpful or sufficient.

Our focus group participants were more fearful that Congress would take no action to fix Social Security and Medicare than that Congress would take some kind of action that would affect the programs negatively or be viewed as too extreme. They uniformly expressed a dim view of Social Security and Medicare’s financial prospects, and they worried that without changes to the programs, Social Security and Medicare would be unlikely to be there for either themselves or their children. Crucially, rather than viewing this as an abstract threat, these voters believed that inaction would result in a loss of their own personal autonomy, resulting in retirees (including themselves) becoming a burden on their families.

The future is “bleak.”

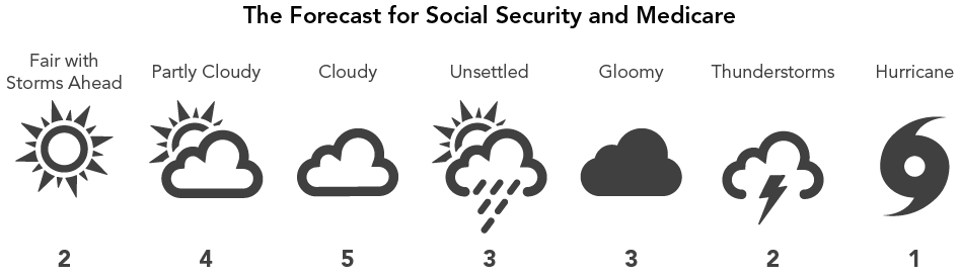

Voters’ concerns for the future of Social Security were vividly conveyed in an exercise where we asked them to describe the programs’ outlook as if they were giving a weather forecast. Most said the program was cloudy or hazy with “severe storms in the future.” Others described the forecast as “gloomy with rough seas” and “bleak.” Several believed the future of Social Security was unsure, reflected in projected forecasts like “unsettled,” “could go either way,” and “unstabilized.” And one woman compared Social Security specifically to Hurricane Katrina, saying “they kept warning and no one listened and they were taken by surprise.”

Their biggest concern is bankruptcy and insolvency of the programs—a worry that outweighed fear of any of the proposed changes. They said that these programs will run out of money and checks will literally start bouncing in the near future, with one participant plainly stating “the consequence of inaction is bankruptcy.” Another agreed, noting, “We do need something to get done because it can’t go on the way it is.” Not a single participant—including the liberal Democrats—argued that Social Security and Medicare were stable with clear skies or a sunny future.

When imagining a future where Social Security and Medicare were not fixed, every one of our participants imagined a bleak existence, not just for the country, but for themselves personally. They described that scenario as being one in which people “can’t get care,” “die earlier,” “are unhealthier,” and “work longer.” That was a future in which “our system has failed and there are no financial supports.” And how do they view people standing in the way of fixing these programs? As one Minnesota Democrat put it, “blissfully ignorant of the issues or too selfish to care about someone else to deal with these problems.”

It’s personal.

Even though our focus group participants were all over the age of 45, with some significantly older and already benefitting from Social Security and Medicare, they all worried that the programs’ financial problems would jeopardize their own benefits—not just those of future retirees. They felt personally threatened and feared a loss of control over their own lives in the absence of changes. One noted, “I don’t think it’s going to be around when I get it.” And another said, “We’ve been told for 30 years it [Social Security] won’t be there and we got into that mindset that we’re not going to get it.”

When asked to write a postcard to their grandchildren in a future where our country had not taken action to shore-up Social Security and Medicare, these participants revealed their deep fear of losing their homes and becoming a burden on their families. One participant wrote to his grandchildren, “You now are responsible for starting a new family while you must also care for your parents.” Another described the consequences to their grandchildren as “that’s why I live off Mom and Daddy. They have to take care of me.” Another said without fixing Social Security, “the payment I am receiving is not enough for me to live by myself so I would like to live with you.” A recurring theme with Medicare was the stability it afforded seniors to stay in their own homes and not burden their children. One woman noted that “you shouldn’t need to be rich to get a lawyer to protect your house” from medical bills. Another described the consequences of inaction more bluntly, “Grandpa and I live in a nursing home. [We] lost our house…and are getting abused.”

Yet our participants were not only focused on their own prospects. Many also referenced the impact on future retirees—in particular, their children and grandchildren. As one stated, “With inaction Social Security will go bankrupt…I feel sorry for future generations.” Another lamented the future they were leaving their children, saying, “I worry that my kids are under 55 and I don’t know what’s going to happen to them. My kids don’t have defined benefit plans, only 401Ks, only 2 legs on that stool so I worry…Social Security is likely to be less than what we have now and I worry about that.” Another put it bluntly: “We gotta start looking out for our kids and grandkids and we want them to be able to afford healthcare.”

Finding #2

Voters don’t want these programs reformed, they want them fixed.

Our participants were generally satisfied with the goals of Social Security and Medicare and do not want major changes to their core missions or functions. Their desire, instead, is to fix the programs (not significantly change their scope) for the future so current seniors and future generations can count on benefits being there. They identified problems with the programs that need fixing to guarantee that benefits for both current and future retirees will be around. They believe we need to act and make fixes to make Social Security stronger, not smaller. While they trust Democrats on these programs, they have no idea what Democrats plan to do to save Social Security and Medicare. And they fear that Republican reforms would shred the social safety net. (Remember, these were Democrats and Independents in our groups.)

Social Security and Medicare are basically good programs.

Our participants wanted to protect benefits for current retirees and ensure the programs are available in the future in mostly the same way they operate now. When asked to select amongst a series of goals for fixing the programs—reducing the costs, making sure everyone pays, making the wealthy pay more, and privatizing among the options—nearly every single participant selected the same 3 top priorities, which most viewed as interlocked:

- Make Social Security and Medicare permanently financially secure.

- Preserve all benefits for current seniors.

- Ensure adequate benefits will be available for future generations.

They favored long-term stability for Social Security and Medicare, but rather than a major overhaul, they don’t want politicians to “change the basic mission.” One of the men with direct experience with Medicare described it as “an excellent program. The way it works, it’s a godsend.”

To resonate with these voters, any plan to fix Social Security and Medicare must stress that it is about protecting and preserving the current programs for retirees and future generations. Our participants viewed these programs as savings accounts which they pay into and receive back later in life. As such, they want to be assured that any changes will not result in them receiving one dime less than they put in.

Times have changed, and the programs need updating.

Our participants did identify problems with Social Security and Medicare that needed fixing. Generally, they felt that certain changes had occurred since the programs were created, and the programs were never updated for future needs. The biggest issues they identified were increases in life expectancy and the cost of living.

Since people are living longer, most participants realized that meant more people receive benefits for longer. As one noted, “The facts are obvious. People are living longer.” And another echoed, “People are living so much longer. That has to be the number one priority.” They also recognized that the number of retirees is increasing as Baby Boomers begin to retire, and the number of workers contributing to the programs isn’t keeping up. One noted, “When it began, there were many, many more workers [supporting retirees].”

But instead of a major remodel, our participants favored incremental steps that would permanently secure the programs and existing levels of benefits for the future. The word “reform” signified big changes to them and implied that it would alter the basic way the programs work. These folks don’t want to restructure the programs; they just want to make minor tweaks to ensure the programs are solvent while maintaining their commitment to current and future retirees. For example, several participants supported a 1 year increase in the retirement age (especially when reminded that people are allowed to choose to retire early for slightly reduced benefits) but refused to consider a 3 year increase even for those currently under 10 years old. Three years just felt too big.

Minor changes weren’t viewed as kicking the can down the road or gutting our generational compact. Rather, they were viewed as solving the “natural causes” of the problems these programs face—as opposed to man-made problems stemming from Congressional inaction or irresponsible management of the programs. As one participant stated, “We owe it to future generations to fix the problem.”

A bipartisan solution is best.

Our participants were comforted by the idea of a bipartisan solution on Social Security and Medicare because each major party is seen to bring a different set of priorities when it comes to these programs. Republicans were seen as more willing to make necessary cuts in waste, but voters feared Republicans would gut the programs. While voters believed Democrats are more committed to ensuring that the programs continue to provide needed benefits, voters feared that Democrats don’t care about the bottom line. If a fix was bipartisan, Democratic support would signal to them that benefits were being protected, and Republican support would indicate that the solution was fiscally responsible.

Given their preconceived views of the two parties, our participants trusted Democrats more to protect Social Security and Medicare, but they worried that Democrats weren’t interested in fixing them. Most participants felt that Democrats would keep benefits where they were and maintain the existing programs, but no one knew of a Democratic plan to save and secure Social Security and Medicare. When asked about the Democratic plan, one man genuinely implored, “Good question. Where’s the plan? Tell me, tell me.” Another said, “The Democrats don’t want to do anything. They want to leave it alone.”

But both the Independents and Democrats to some extent feared Republicans plans for reforming Social Security and Medicare. Most participants believed that the Republicans would privatize Social Security and cut benefits. After the financial crisis and years of instability on Wall Street, there was little to no support for private accounts, except among a handful of younger, Independent men. One woman’s response to privatization? “The stock market, oh please, God no.” Securing their retirement was their goal, and privatization was seen as the opposite of security—forcing them to gamble their funds without the benefit of guidance or understanding of a volatile market.

Generally, Republican efforts to “fix” Social Security and Medicare were viewed as a step in a process of ending the programs. One participant guessed, “They would leave benefits the same for now but eventually privatize.” Most felt benefits would be cut, the retirement age would be significantly increased, and the very wealthy would be benefitted through a partisan Republican reform plan. However, unprompted, many participants mentioned Rep. Paul Ryan as honorable for at least trying to solve the problems and having a plan and would give similar kudos to anyone in Washington offering real solutions. As one noted, “We may not all agree with the Republican plan, but at least someone [Ryan] is standing up, willing to take the political hits, and putting something forth.” The specifics of the Ryan plan were well-received, though, only by a small number of the younger, Independent men, while most others strongly opposed them.

When it came down to it, participants wanted a bipartisan solution, because they could then feel confident that Democrats would ensure benefits would be protected and Republicans would ensure that the programs would be managed well and that we were not overspending. Everyone, including the self-identified Democrats, worried that Democratic politicians were too quick to spend money and not concerned enough about rooting out mismanagement. One participant voiced it this way, “I think they mean well, but they are terrible managers.” Another used a metaphor to describe it:

The difference between Republicans and Democrats is, the kids need shoes. The Republicans say, “ok, how are we going to pay for these shoes?” And, the Democrats say “let’s get the kids the shoes and we’ll worry about paying for it afterwards.” … The kids will either go without shoes with the Republicans…but the Democrats sometimes are more willing to endow these entitlement programs without the fiscal responsibility of figuring out how we’re all going to pay for it down the line.

Based on their characterizations of the parties, they believed that a deal involving both sides would be the best way to achieve the changes we need while protecting the benefits we have.

Finding #3

Voters perceive significant waste, fraud, and abuse in Social Security and Medicare.

Our participants identified waste, fraud, and abuse as significant threats to the programs as well. This issue came up despite the fact that we never raised it in the focus groups. When forced to choose between lists of priorities and policy options that didn’t include addressing waste, fraud, and abuse, every single group brought up the issue spontaneously and demanded it be included in the discussion. They singled out two major causes of insolvency in this vein: 1) undeserving people receiving benefits, and 2) Congress borrowing from the Social Security trust fund to pay for other spending. In their view, these were more significant threats than anything hospitals, doctors, or insurance companies were doing to game the system. They believe if we seriously dealt with waste, fraud, and abuse, many of the problems with the programs would be solved.

Undeserving beneficiaries are looting the pot.

Our participants consistently highlighted fraud as a significant threat—and by fraud they meant people who hadn’t paid in receiving benefits. Many cited specific examples of fraud in their families or communities that they were aware of. Fraud by beneficiaries was viewed as a bigger threat than fraud or abuse by insurance companies, doctors, or hospitals. Since these voters viewed the money in these programs as their money—not federal dollars but the people’s dollars—they were livid about the notion that people who haven’t paid into the system were stealing their benefits. This is their money, and they don’t want it wasted or pilfered.

- “The funding isn’t going into the right channels. People are getting it who don’t really deserve it.”

- “Riddled with fraud.”

- “My number one irritant is trying to eliminate fraud.”

A big reason for this concern was our participants’ general understanding of Social Security as a “savings account.” They believed that there must be fraud, waste, and abuse occurring, because they paid into the program, so if the money isn’t there, someone must have taken it. One noted, “I’m feeling like if I put my money in, I should get my money.”

Congress is borrowing from the trust fund to pay for other programs.

Another result of the “savings account” metaphor was that participants assumed there must be serious Congressional mismanagement of Social Security funds. Many participants argued that if the programs are in as much trouble as some policymakers say, it must be because Congress was raiding the trust fund to pay for other budget items. Social Security funds should be sacrosanct in their view, and they have already paid in for their own benefits, so most of the funding problems must be due to the government borrowing their retirement money for other programs.

They openly pondered what had happened to Vice President Gore’s lockbox. One noted, “If it was managed correctly [it would be fine].” And another lamented, “You keep hearing about the government borrowing from this fund to pay that fund.” And another said, “Social Security is supposed to be sacred.”

This idea of Congress raiding their retirement money to pay for other programs cast doubt on politicians’ motives for reform. That meant that when the issue was framed as needing to reform Social Security and Medicare to fix the deficit, they balked. One argued, “These programs shouldn’t have anything to do with the deficit.” They even pushed back against the idea of talking about the programs as part of the “federal budget.” When we posed an argument about Social Security and Medicare costs rising to take up 70% of the federal dollar in the future, they became angry and insisted, “It’s not a federal dollar. It wasn’t supposed to be theirs to spend.” They were very clear that when we talk about Social Security, in particular, we are talking about their money—not federal dollars.

Finding #4

Voters see Social Security and Medicare as “earned benefit” programs—not “entitlements.

Even the term “entitlement program” rubbed our participants the wrong way. When asked to which programs that term referred, they were confused and could not agree on an answer in any of the four group discussions. To some, the word “entitlements” was negative and included a host of welfare and other programs. Others said “entitlement” meant you’re entitled to something so you must have paid in for it, but then they mentioned veterans benefits and other programs for which Americans pay (monetarily or otherwise).

One participant noted: “Social Security is not an entitlement…because it is something we paid for.” Some said Social Security and Medicare were entitlement programs but upon further discussion thought there should be a better way to describe them. One participant suggested calling them “earned benefits,” since it avoided the negative connotation of the word “entitlement” and indicated that beneficiaries had paid into the system and earned the benefits they received.

The language of “entitlements” raised all sorts of sirens—from the “entitled” wealthy who expect privilege to lazy and undeserving people who haven’t contributed receiving benefits. To these voters, Social Security and Medicare were better described as “earned benefits”—money they had earned and that was put aside for their use.

Recommendations

These insights may spur many thoughts about how to more effectively present Social Security and Medicare changes to these voters. But we have one overarching recommendation: frame your plan as fixing Social Security and Medicare so they are there for today’s and tomorrow’s retirees. That means:

- It’s about fixing the programs, not reducing the deficit.

- Proposed changes are modest but necessary;*

- The fix will solve the problem for good;

- Americans will continue to get out of these programs what they pay in;

- The solution includes a major anti-fraud effort; and,

- It has bipartisan support.

Where possible, it may be wise to suggest incremental and self-adjusting changes, e.g. raising the retirement age one year and then pegging it to life expectancy rather than spelling out how many years it would increase now even for the very young.

This issue will never be politically easy, and voters know that, too. Our participants recognized the risk for politicians who try and fix Social Security and Medicare. But they described policymakers who are willing to champion the cause valiantly—as “brave,” “courageous,” “making tough decisions,” and “setting aside their own interests.” Several voters were hopeful that “the general populace would probably reward them [for action].” Another noted, “If they try to solve it…I am going to give those people a lot of credit.” In contrast, they described those who stand in the way of fixing the problems as cowardly and self-interested, saying: “Everybody is worried about getting re-elected”; “They are kicking the can down the road”; “It is easier not to make the tough choices”; and “They have forgotten that it says we the people in the Constitution, not me the Senator.”

If a Social Security and Medicare proposal is responsive to the problems they see and conveys a desire to secure the programs for the future rather than paying for other governmental budget priorities, these voters would be open to incremental changes that will make the programs solvent for the long term.