Report Published August 19, 2015 · Updated August 19, 2015 · 23 minute read

Rethinking Medicare Enrollment: Make High-Value Health Coverage the Easy Choice

David Kendall & Elizabeth Quill

Author and baby boomer advocate Carol Osborn filled six large folders with hundreds of brochures about health insurance plan options before she enrolled in Medicare.1 Her research also involved dozens of calls to government offices, financial advisors, and public counseling services to determine the best plan for her. She says enrolling in Medicare is her second greatest late-in-life accomplishment. Getting a PhD in her 50s is her first.

Choosing the right Medicare plan should not be that hard. Millions of older Americans end up paying hundreds of dollars extra for health care because the choices overwhelm them. Those extra costs get multiplied in Medicare because it pays more for uncoordinated care that leads to unnecessary expenses. Beneficiaries should have a way to easily select a plan based on their needs and preferences. For beneficiaries who prefer to be completely passive about their choice, Medicare should no longer indiscriminately assign them to the original, fee-for-service Medicare plan without regard to the cost and quality of care under alternative private plans. Instead, the default choice should be the highest-value plan for beneficiaries in their area, which could be original Medicare or a private plan—and they would be free to change plans. Not only would new beneficiaries be happier because they would be saving an average of $1,704 in annual premiums, changing the enrollment process for new Medicare beneficiaries would save the federal government $57.3 billion over ten years.2

This idea brief is one of a series of Third Way proposals that cuts waste in health care by removing obstacles to quality patient care. This approach directly improves the patient experience—when patients stay healthy, or get better quicker, they need less care. Our proposals come from innovative ideas pioneered by health care professionals and organizations, and show how to scale successful pilots from red and blue states. Together, they make cutting waste a policy agenda instead of a mere slogan.

What Is Stopping Patients From Enrolling in High-Value Plans?

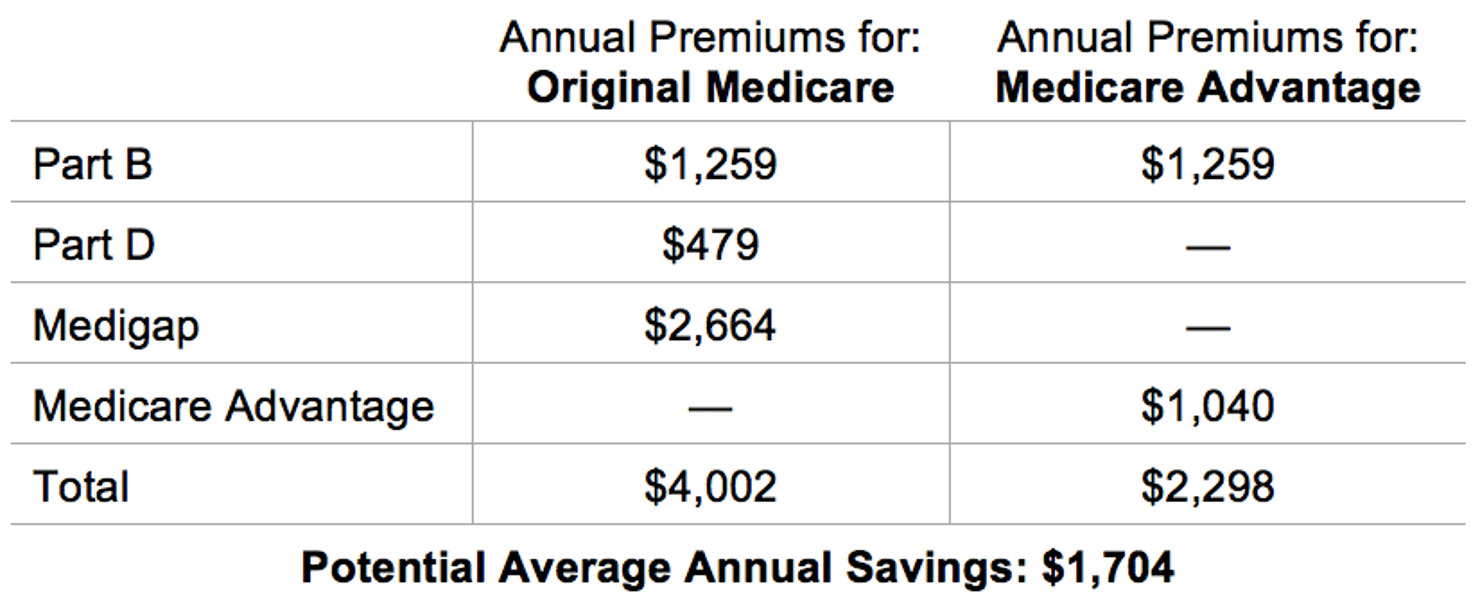

When Medicare beneficiaries have trouble shopping for a health plan, they can end up spending more and getting inadequate care. A beneficiary who keeps the automatic enrollment in original Medicare faces separate payments for Part D coverage (which covers prescription drugs) and Medigap (which covers out-of-pocket expenses that Medicare does not). Together with the Part B premium, beneficiaries currently pay an average of $4,002 a year (based on 2014 average premiums).3 But, a high quality Medicare Advantage plan that has a four or five star rating costs $1,704 less than coverage under original Medicare. The cost savings, as shown in the chart below, come from the fact that Medicare Advantage plans often include prescription drug and supplemental benefits, making the additional purchase of Part D and Medigap coverage unnecessary. While these savings do not include the differences in out-of-pocket costs between original Medicare and Medicare Advantage due to limited data, it is important to note that about half the Medigap plans currently do not have any cost-sharing, which could reduce the cost advantage of Medicare Advantage over Medigap (although starting in 2020, new Medicare beneficiaries will not no longer have the option of a Medigap plan without cost-sharing). However, this difference is not as big for new beneficiaries who might be healthier and require fewer medical services.

Beneficiaries' Premiums for Medicare Coverage Options

Note: premium amounts are for 2014 and do not include the cost of deductibles, copayments, coinsurance, and income-related premiums.

Why is it so hard to choose a good plan? One big problem is that beneficiaries do not have access to information about the quality of care in original Medicare for their area as they do for Medicare Advantage plans. National studies about the quality of care (based on current, but limited, research) indicate that beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans can receive better quality care, on average, than those in original Medicare.4 But original, fee-for-service Medicare does not regularly assess and report on its quality for each local area, leaving consumers in the dark. In contrast, Medicare Advantage plans are rated on the quality of their care and customer satisfaction, which the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services ranks using one to five stars. For a full discussion of the lack of quality rankings in original Medicare, see Third Way’s idea brief, “Give Medicare Beneficiaries Complete Information about their Plans.”5

Another big problem is the challenge that anyone faces when making a complex choice. Behavioral economists have broken down the challenge into a sequence of three separate issues: getting overwhelmed with the initial set of plan choices, getting stuck in making a new choice, and favoring a current plan over something better.

First, individuals can get easily overwhelmed by too much information and too many choices.

On average, beneficiaries have 18 Medicare Advantage plan choices plus original Medicare.6 Those choosing original Medicare have an additional 30 choices, on average, for Part D prescription drug plans and a multitude of choices for supplemental medical coverage.7

Choice overload, a term used by behavioral economists, explains how an individual can get overwhelmed with so many choices. This leads individuals to either make a poor choice—or no choice at all. Research has shown that after a certain point, an increase in options and information about those options in fact causes people to process a smaller fraction of the choices and information.8

This overload often results in random and uninformed choices, yet people are unaware that they’ve likely made a poor choice.9 One study examined Swiss health care consumers who have a health care system very similar to the ACA marketplaces, including the ability to choose many health plans. In fact, they have to choose between 30 to 75 health plans.10 Information on plans, including premium amounts, was widely available. Researchers anticipated that with increased plans, people would switch plans frequently resulting in substantial price competition.11 However, people who had more alternatives were less likely to switch plans because as the number of alternative plans increased, people became more overwhelmed by the number of choices.12 The result was greater price variation, which indicates weaker competitive forces.13 So why do individuals stick with a choice, even if it is a bad one?

Second, individuals can favor a previous choice over making a new choice.

Individuals are influenced substantially by their previous choices. The investment of money, effort, or time that has been put into old endeavors is sometimes given a more substantial weight and can prevent better decision-making.14 Known as the sunk cost effect, this problem explains why individuals continue a project or activity when, instead, they should abandon it.15

When considering whether to switch health plans, individuals may worry about issues likes changing physicians, co-pays, and deductibles. Dealing with their current health plan likely has become a part of the individual’s routine, and they know how to deal with problems that may arise. They often find these perceived costs of switching hard to ignore.16 The consequences of changing plans may seem to outweigh the benefits.17

Third, once a consumer chooses an initial health plan, they are more likely to stay in it even in the face of better options.

Status quo bias explains the tendency for people to accept things as they are and avoid making new decisions.18 A study that looked at retirement investments of university faculty nationwide found the faculty members overwhelmingly remained with their initial choice of investments regardless of better investment opportunities.19

Studies have shown that adult employees rarely switch from the health plan they chose at the start of employment.20 In 2010, less than 2.5% of adults under 65 with employer coverage switched their coverage with the goal of reducing their costs or switching to a better value plan.21 Another study examined the health plans offered to Harvard employees.22 The study found that once employees had made that initial health plan choice, only 3% of employees switched their plans in subsequent years.23

When Medicare beneficiaries have difficulty making an initial coverage choice and then with a poor choice, the consequences can be far reaching. It can impact the cost and quality of their health care potentially for the rest of their lives. For this reason, it is all the more important to provide Medicare beneficiaries with support in making their choice, as well as a safe default choice when they do not make their own choice.

Where Are Innovations Happening?

In recent years, lawmakers have developed policies that encourage the use of a safe default choice to help individuals save for retirement. When employers automatically enroll employees in a retirement policy, 86% will follow through and contribute money to the retirement account, but when employees must sign themselves up, the number of employees who save drops to 49%. This kind of research has led to retirement policies that encourage better default choices.24

Applying better default choices to health insurance choices is just getting started, but one area where defaults are currently in use is in the dual eligible Medicare and Medicaid population. Beneficiaries who are dually eligible for the Medicare and Medicaid programs account for a disproportionate amount of spending in each program. Dual eligibles face many problems due to their health conditions, low-incomes, or disabilities. The primary problem is that they receive coverage two very different and uncoordinated programs: Medicare and Medicaid. Moreover, when they try to navigate and select coverage from the dozens of choices available to them, they easily feel overwhelmed and refrain from making any choice at all. Their default enrollment is the unmanaged and uncoordinated fee-for-service programs in Medicare and Medicaid. The lack of coordination, which can have severe cost and quality consequences, has led many states to participate in a demonstration program with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and private health plans that integrates the Medicaid and Medicare benefits into one plan, which becomes the default plan for enrollment if beneficiaries do not make an active choice.

For example, Massachusetts is setting up an effective default mechanism for dual eligible beneficiaries. Called One Care: Mass Health plus Medicare, the state has set contracts with three different private plans to integrate Medicaid and Medicare financing and provide person-centered, comprehensive Medicaid and Medicare benefits.25 After a period of voluntary enrollment, Massachusetts automatically assigns beneficiaries to a default plan during one of three rounds throughout the first year of implementation.26 Beneficiaries can then choose a different One Care plan or retain their prior Medicare and Medicaid options.27 As of June 2015, 17,705 dual eligible beneficiaries were enrolled in one of three One Care plans.28 Approximately 115,000 full dual eligible adults age 21-64 are included in the target population.29

Another success comes from Picwell, a new company with leadership from professors and graduates at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. Picwell makes health plan recommendations using a sophisticated prediction of a person’s health care costs for the upcoming year based on an individual’s health insurance claims experience from previous years. It also takes into account personal preferences, such as a consumer’s preferences about the importance of customer satisfaction ratings and risk tolerance for high out-of-pocket costs.30 All told, it accounts for an incredible 900,000 variables involved in a health plan choice.31

Such tools have proven useful for employees whose employers are offering a broad array of choices. Aon Hewitt, a private health insurance exchange for employers, has found that 9 of every 10 employees use at least one of the decision support tools it offers to employees.32

How Can We Bring Solutions To Scale?

Policymakers should simplify automatic enrollment and comparison shopping for Medicare—which would lower costs for beneficiaries, give them quality care, and reduce unnecessary Medicare spending. The following three steps would accomplish this goal.

Offer Medicare beneficiaries decision support tools for choosing coverage. Computer-based decision aids help patients align their preferences and values to the insurance coverage that is right for them.33 It can eliminate choice overload through a strategic presentation of choices called “sequential elimination”, which improves decision-making without eliminating choices or overwhelming consumers. This involves a process of presenting consumers with a series of questions and eliminating the options that do not fit the consumers’ preferences. This process systematically narrows the choices to the ideal decisions for that person.34 In health care, this process would guide a patient through a series of questions and eliminate a few options at a time.35

Beneficiaries should have access to such tools directly through a website or through one of the many organizations that assist beneficiaries like insurance agents and State Health Insurance Assistance Programs. Such programs are critical for helping beneficiaries who do not have access to the Internet or simply need extra help with this challenging task. Beneficiaries also need a centralized source for enrolling in whatever Medicare Advantage plan, Medigap, or Part D plan they choose in order to make selecting a plan as easy as possible.

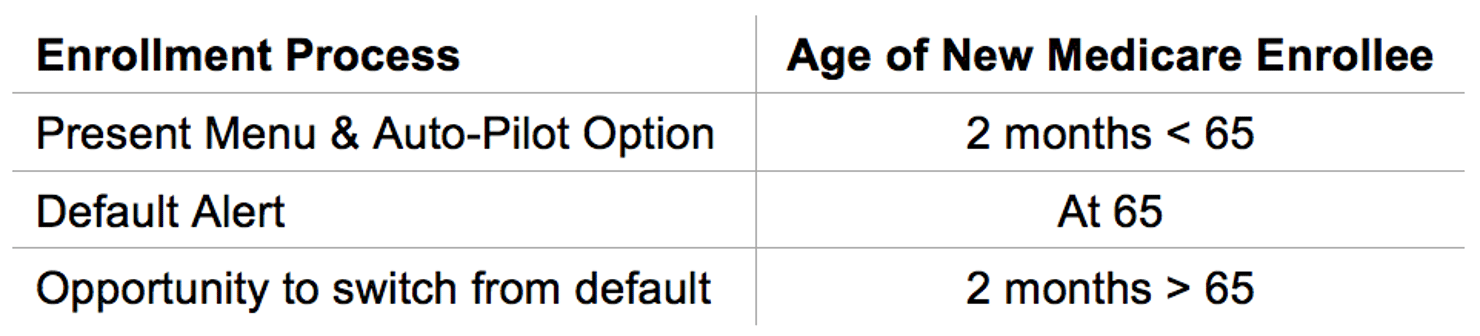

Allow all new and current beneficiaries to set their own default preferences for a plan choice. A better enrollment process for new Medicare beneficiaries would help current beneficiaries, too. All should have the opportunity to use the decision support tools to choose coverage themselves or to rely on the recommendations of a decision support tool.

Here’s how this could work: beneficiaries would enter their health plan preferences (e.g., do they prefer greater choice of doctors over lower costs) into the decision support tool, and their health plan enrollment would be automatically chosen based on their preferences. Initially, this “auto-pilot” feature would be based on simple information like whether the patient would prefer specific doctors to be in the network. Over time, beneficiaries could tap into more sophisticated information systems to guide their enrollment. For example, they could authorize access to a summary of their health insurance claims so that their specific health care problems and anticipated costs would guide them to plans with the best care at the lowest price for their needs. In developing an auto-pilot system, CMS would have to test different tools—public and private —at every step in their development in order to prevent unintended consequences.

The auto-pilot feature would also allow beneficiaries to set their choice of coverage to be the same as previously held. If they let the auto-pilot choose a plan for them, they would always have the opportunity to change once they saw what plan had been selected.

New beneficiaries who do not make a choice should be automatically enrolled into highest-value plan. After a period of open enrollment, new beneficiaries who do not choose a health plan should be automatically enrolled in a benchmark plan (defined in questions and answers below) that provides the highest value for their region.36 Beneficiaries would stay in their current health plan if it is one of the benchmark plans available through Medicare. If they did not like the plan, they could switch out of it before the coverage begins. The formula for determining benchmark plans would be based on premiums, out-of-pocket costs, and quality scores. The premium for traditional Medicare in each region should be based on the average premiums for the most popular Medigap and Part D plans in the area and should be adjusted up or down depending on Medicare Advantage plan benefits. All current beneficiaries should be encouraged to examine their choices annually with reminders and simple-to-use comparison tools.

Potential Savings

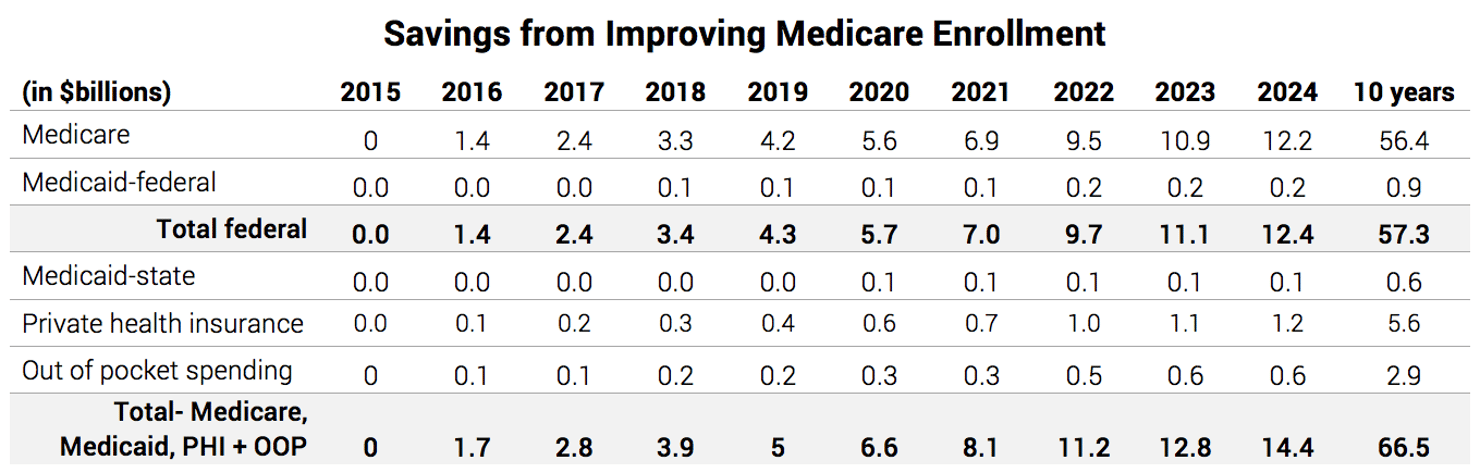

Changing the Medicare enrollment process by setting the default choice of health plan to the lowest-cost, highest-quality plan would save the federal government $57.3 billion over 10 years.37 And state governments would save a total $600 million in Medicaid costs because some Medicare beneficiaries receive financial assistance with their annual premiums from Medicaid. Total savings in national health expenditures would be $66.5 billion over ten years. The chart below shows the savings year-by-year.

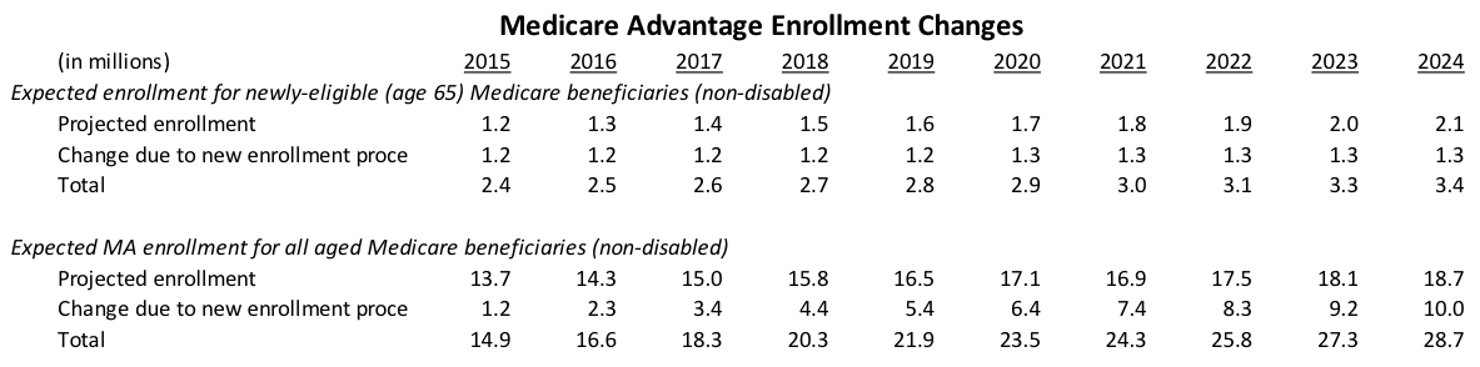

Savings for Medicare beneficiaries would also be significant. The average annual savings for new Medicare beneficiaries which, as previously stated, is $1,704 a year based on 2014 premiums. Each year, the increase in the number of Medicare Advantage enrollees due to the new enrollment process would be 1.2 to 1.3 million. By 2023, Medicare Advantage enrollment would increase from a projected level of 18.1 million to a total 27.3 million. The chart below show the yearly changes in Medicare Advantage enrollment.

Questions and Responses

How do you calculate the highest-value plan?

The highest-value plan is calculated by creating a formula with a value rating system between 0 and 100. This is calculated by multiplying the quality rating by the price of the coverage, then indexing to 100. One hundred would be the top score. Plans that tie each other, because their index level is statistically within the same range, would have new beneficiaries assigned to them on an alternating basis so that no single plan gets all the new beneficiaries. The price of coverage would include premiums and average out-of-pocket expenses.

What if the highest-value plan filled up with new enrollees?

When the highest-value plans are at capacity, the consumer will be put in the next highest-value plan. For example, in Medicare, the default enrollment of beneficiaries in a benchmark plan would depend on how many people the plan had the capacity to enroll. Plans would state their capacity limits upfront, and CMS would have to assess each month whether the default enrollments were going to exceed the capacity. If the benchmark plan’s enrollment was going to exceed its capacity, then Medicare administrators would choose the next highest ranked plan as the new benchmark plan. An exception would be made for new beneficiaries who are already enrolled in the primary benchmark plan. They would always be placed in that benchmark plan by default.

Is there a danger that the intense competition among plans to be the highest value would produce unintended consequences?

Yes. For example, a plan might overstate its capacity to accept new enrollees in order to get more business. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will need some regulatory flexibility in designating the number of plans that will accept the default enrollment. Should it determine that the beneficiaries’ interests would be best served by designating a slightly broader range of plans at the highest value, then it would alternate assigning beneficiaries to those plans for the default enrollment.

How would consumers switch out of a health plan they don’t like?

Switching plans would be easy during the open enrollment period. For Medicare, beneficiaries could make one call to a toll-free phone number or go to a website through Medicare.gov. New retirees who were automatically enrolled in the highest-quality, lowest-cost plan would be able to switch out of that plan up to one month after turning 65. After the first year, they could switch plans during an annual open enrollment period that just occurs today with the private, Medicare Advantage plans.

Would Medicare beneficiaries still be guaranteed the same Medicare benefits they receive today?

Yes, all Medicare beneficiaries, regardless of whether they are in a public or private health plan, would be guaranteed all Medicare Part A and B benefits. The only major change is that new beneficiaries would no longer be automatically enrolled in traditional Medicare in regions where it is not the highest-quality, lowest-cost plan. Instead they would start in the lowest-cost, highest-quality plan and could switch to another plan if they wished.

Would the new default enrollment affect people qualifying for Medicare due to a disability?

No, disabled Americans who qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance and Medicare have very different needs from the typical older American. They do need much better information to make a good decision about their coverage, and defining a good default plan would require additional experience and research on the quality of care they need and receive. Lastly, if they were automatically enrolled in Medicare Advantage plan, they would lose the opportunity to switch to a Medigap plan used in conjunction with original Medicare. While Medigap enrollment restrictions very greatly from state to state, disabled Americans cannot switch back to a Medigap policy after their initial enrollment period in Medicare ends.

How would the new enrollment process affect the current information beneficiaries receive about their plans and plan changes?

Each year, Medicare beneficiaries with Part D prescription drug coverage receive an annual notice of change and evidence of coverage documents by mail. These lengthy documents (evidence of coverage can be hundreds of pages) provide thorough and reliable information, but can be overwhelming because they don’t address the specific circumstances of each beneficiary. CMS could streamline the current communications with beneficiaries by allowing for electronic delivery of the important, but voluminous, information and, instead, prioritize information customized to a beneficiary’s situation. CMS could customize its communication with beneficiaries using the same kinds of data about health care needs that should also be available directly to beneficiaries to help them choose a plan.

How does Medicare measure the quality of private health plans?

Medicare rates health plans from one to five stars. The ratings come from 32 measures of clinical quality, patient experience, and contract performance for Medicare Advantage plans and 15 measures for Part D plans.38 Of the beneficiaries in a Medicare Advantage plan, about one-third are enrolled in a four or five star plan.39 Traditional Medicare should be required to report on its quality of care.40 This would be similar to the quality reporting that Medicare Advantage plans do currently. That would give beneficiaries access to complete information to compare their options before they enroll. Collecting and reporting quality information will take time and investment, but the result will be a new level of accountability in traditional Medicare.

How could Medicare measure the quality in the original public plan?

Although Medicare collects an increasing amount of quality information about providers, ranging from physicians to nursing homes, this information does not show how well the traditional Medicare plan functions as a plan or as compared with Medicare Advantage plans. One entity that could collect the necessary information in a manner similar to private Medicare Advantage plans are the Quality Improvement Organizations (QIOs). QIOs contract with Medicare to review medical claims, help beneficiaries with complaints about their quality of care, and improve overall quality of care. They have the experience to review the medical charts and insurance claims to measure the quality of care.

Why would more enrollment in high-quality health plans save money?

Medicare Advantage health plans with four to five star quality ratings, on average, save Medicare money. Like high-quality manufacturing that reduces wasteful mistakes, high-quality health plans eliminate waste from preventable health care problems (e.g. hospital-acquired infections). Through the focused efforts of health professionals and health plan administrators, such problems can be dramatically reduced or even eliminated.

Do the savings estimates account for changes in Medicare payments to health plans?

Yes. The Affordable Care Act made several changes to payments to Medicare Advantage plans. These changes are phased-in through 2017. The savings estimates are based on the changes in payment rates by county.

How would a Medicare default choice program affect similar programs for dual eligible and Part D beneficiaries?

Medicare has approved demonstration programs in several states that allow beneficiaries who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid to be automatically enrolled in a single health plan that covers all of their needs.41 The purpose is to align the financial incentives under Medicare and Medicaid so that patients end up with the care that is the best for them, not the care that is the least expensive for one program or the other. Nonetheless, automatically changing a plan for beneficiaries with many health care needs can disrupt existing arrangements for their care. A Medicare default choice program would affect only newly eligible beneficiaries who have fewer established relationships with providers.

Medicare Part D automatically enrolls beneficiaries in a low-income program if they are already enrolled in other low-income programs like Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for seniors. As part of this simple and effective enrollment method, low-income beneficiaries are automatically assigned to a Part D plan if they do not select one. One problem is that low-income beneficiaries can be automatically reassigned annually to another Part D plan if their plan loses its eligibility for the low-income program. 42 For the Medicare default choice program, beneficiaries would not be reassigned after the initial default enrollment. If a default plan’s costs rose or quality declined, however, Medicare could actively encourage those default enrollees to consider other options or change their enrollment if they did not choose themselves.

With all automatic enrollment programs, Medicare should minimize disruption and provide good choices and support to beneficiaries about their choices. That is important to prevent beneficiaries who are automatically assigned to a plan from being confused or even resentful about it.

How would the geographic regions for benchmark plans be defined?

In order to make meaningful comparisons about costs and quality, beneficiaries need results that are relevant to where they live. Aggregating this information at the state level would be too broad and not account for local differences. County-level data would not necessarily correspond to provider service areas. Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) might be a suitable set of boundaries. For assessing Medicare Advantage plans, MSAs also make sense except where they cross state lines because health plans are state-regulated and their operations are often state-based. Only within the District of Columbia MSA would a cross-MSA region be fully justifiable due to the tradition of health plans’ operations crossing state boundaries. Of course, quality measures aggregated at the MSA level would require changes in reporting procedures as well as tests to ensure statistically reliable results.

The Medicare Advantage five-star rating system would also require some adjustments to account for regional boundaries. Star ratings today correspond to health plans’ contracts with Medicare, which can be multi-state. The reporting by contract would have to be changed to reporting by a MSA or any other regional boundary. Similar changes would need to occur Medicare Part D plans.

How could other care options like Accountable Care Organizations be offered as choices for beneficiaries?

The advantage of a single menu of all plan options for Medicare beneficiaries is that new choices are easy to add. For example, Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) has proposed Better Care Plans that combine elements of accountable care organizations and chronic care management.43 The Bipartisan Policy Center has proposed a similar idea called Medicare Networks.44 These new options could be offered side-by-side with existing coverage options. They could also receive star ratings for their quality just as Medicare Advantage plans already do.