Report Published August 3, 2023 · 11 minute read

Supply Chains and Value Chains, Explained

Joshua Kendall, Gabe Horwitz, & Zach Moller

Americans spent a whopping $5.9 trillion last year on everything from dishwashers and dog beds to trampolines and TVs.1 Each of those products went on a unique journey—from creative ideas to raw materials, to a finished product shipped by air, sea, or land. That journey has been under increasing scrutiny as the pandemic ground supply chains to a halt, visible in spontaneously empty shelves that formerly contained toilet paper or specific brands of cereal. While many of those issues have now been resolved, new supply chain issues have emerged as a result of the war in Ukraine and complicated issues with China. One example is beyond the war’s human cost, countries and products that depended on Ukraine and Russia’s combined 24% of global wheat exports are feeling a supply chain strain.2

To help policymakers understand the intricate steps that go into making a product—and the implication that journey has on jobs and the broader economy—we dig into supply chains and their close sibling value chains below. Specifically, we examine how products are made and brought to consumers, the impact on jobs, and questions over how much should be made in America.

Concept to Constituent: How products are made and brought to consumers

A product’s journey from an inventor’s mind to a consumer’s hand involves numerous steps. The different parts of that process can be broken down into a supply chain and value chain.

Supply Chains

A supply chain details the steps by which raw materials are turned into finished products.3 A supply chain can exist entirely within one country or could stretch across many different borders. For example, Wilson’s “The Duke” American football has its entire supply chain in the United States.4 It’s made from leather crafted in an American factory from cows that are processed in American slaughterhouses and fed on American grass and corn.5 Conversely, automotive vehicles are extremely complex machines that often include parts from all over the world.

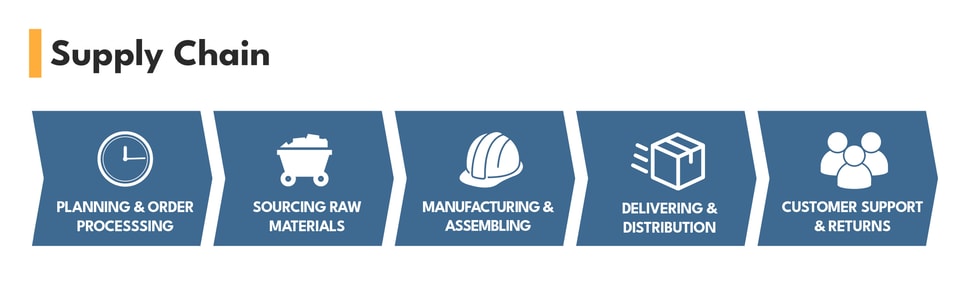

While each product has its own unique supply chain, the general steps include:6

- YETI personnel in the United States forecast demand and process orders for drinkware.

- Third-party manufacturers located in China, Malaysia, Mexico, and Thailand create the mugs from materials including polyethylene, polyurethane, and stainless steel, to name a few.8

- YETI works closely with manufacturers to connect them with raw and intermediate materials suppliers, direct production, and ensure product quality and manufacturing efficiency.

- International shipping companies such as Germany-based Deutsche Post AG transport the finished mugs to distribution centers in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands.

By examining a product’s supply chain, one can understand the multinational effort to supply the global economy.

Value Chains

Rather than focusing solely on a good’s physical production, a value chain represents how each step in a product’s lifecycle contributes to its eventual value.9 While a value chain could exist entirely within a single nation, it is usually applied to internationally traded goods.10 By tracing a product’s value chain, we can see how some of the dollars we spend on foreign goods end up back in our domestic pockets.

There are numerous steps in a value chain, but these can be boiled down to the following:11

Returning to YETI, examining the product through its value chain provides an understanding of its value beyond its physical components.13

- YETI marketers in the United States study industry trends and consumer preferences.

- American development staff create and test prototypes. Designs are shared with brand ambassadors in the United States and a handful of international markets to ensure the product is usable.

- YETI development staff distribute product molds and machinery to manufacturing partners. This begins the production process which includes technical operations, quality assurance, and manufacturing.

- YETI markets the product through traditional, digital, and social media, product ambassadors, and original short films. This activity is focused in the United States, but also exists in Europe, the English-speaking Pacific, and Japan.

- In the United States, mugs journey from distribution centers in Memphis, Tennessee and Salt Lake City, Utah to the stores in which they will be sold. In international markets, distribution centers are housed in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and the Netherlands.

- Consumers purchase the product either from retailers, one of YETI’s 13 owned and operated stores, or from an online marketplace.

- Support staff are available for customers to contact with questions and concerns.

The sale of each mug pays for this entire process. When someone purchases a brand-new YETI tumbler, a portion of that $38 goes to Thai manufacturers, American designers, German logistics companies, Dutch warehousing staff, and a litany of other people that contributed value to the product.

Jobs: How many, where are they, and what are they doing

Making a product evokes images of workers clad in protective gear on an assembly line, and shipping a product conjures up a port worker or truck driver. But that overlooks the complexity of 21st century production. With global value chains and supply chains, American exports and imports both have an effect on US jobs. The global interconnectedness supports American exports and the requisite jobs—while simultaneously broadening the array of raw materials and intermediate goods used in American manufacturing. Imports also support American jobs as the value chain demonstrates how a portion of the sales price of imported items is often paid to American workers.

Export Jobs

According to the Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration, exports support 9 million jobs in the United States, roughly 6% of the nation’s workforce.14 A quarter of these jobs are in manufacturing, but other value-adding types of jobs such as professional services, finance, and transportation feature prominently.

For the manufacturing and transportation/warehousing industries, exports are particularly important. Respectively, exports support 20% and 13% of all jobs in those sectors.15 Further, exports are pivotal to the goods-producing parts of the American economy. Exports support 20% of the nation’s goods-producing jobs.16

Import Jobs

Given varying definitions of what constitutes an “import-supported job” and the mathematical approach to estimating them, it is challenging to approximate how many jobs imports support. Some estimates range as high as 21 million jobs, about 16% of national employment.17 This includes jobs ranging from retail salespeople to manufacturing firms that import parts and materials and often overlap with export-supported jobs. For example, a dock worker is equally supported by imports and exports. Roughly 40% of all US employees work at firms that import goods or services, even if their specific jobs don’t rely on imports.18

Jobs by Geography and Industry

There is significant variation in trade’s impact on employment based on geography and industry. For example, in Texas, exports support 7.7% of the state’s workforce, while they underpin only 1.3% of Wyoming workers.19 Geographic diversity is due in large part to a state’s proximity to borders, as it is much easier for California to have a thriving port industry relative to South Dakota. Conversely, industrial variation in exports stems mostly from the kinds of products they produce. It is much easier to export Harley Davidsons than haircuts.20 Further, any given industry may have specialized jobs beyond the production process, such as HAZMAT-qualified drivers for transporting certain chemicals and other raw materials.

The Global Question: To trade or not to trade?

Even though the vast majority of supply chains are global, there is a longstanding debate over whether Americans can and should make everything ourselves. At its core, this is a balancing act—between reliability, variety, available labor, and a host of other decisions. Both perspectives have economic benefits and ramifications, and wise trade policy balances the two.

Here or there?

Over the years, the United States has at times pursued targeted policies to promote self-sufficiency and limited trade (also known as autarky in its extreme). For example, the CHIPS Act acknowledges that semiconductors are too important to the American economy to rely predominantly on international suppliers.21 The act has incentivized billions of investment dollars to build factories and hire Americans. Further, the recent Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act included a provision which preferences American materials and manufactured products.22 These bills had clear tradeoffs on cost, security, and promotion of local jobs.

However, there are some goods or materials we simply cannot produce here. Americans love coffee, but the nation’s climate prohibits us from growing enough to satisfy our habit.23 Devoting all of Hawaii’s land to coffee cultivation wouldn’t come close.

Further, trade gives the US economy flexibility—in what we consume, produce, and prioritize in the sectors and skills at which we are comparatively skilled.24 Our workforce has exceptionally skilled scientists, engineers, and managers, which allows many Americans to focus on those jobs while other countries focus on different parts of the production process. The value chain demonstrates how these indirectly related fields contribute to trade-supported jobs, as they provide some of the value that makes trade efficient enough to employ longshoremen, truck drivers, and factory workers.

Policymakers must also recognize how trade can sometimes lead to job loss for domestic workers. Programs like Trade Adjustment Assistance are key aspects of trade policy that support the entire US workforce, and even more can be done to help workers with job and skill training before economic change happens.25

Friend/Near shoring

In the debate over where to make things, there is a push by some to do more “friend-shoring” and “nearshoring.” These phrases refer to prioritizing trade with neighboring countries (nearshoring) or our formal or informal allies (friend-shoring). Both efforts are responses to some of the vulnerabilities found in international trade—from COVID-induced shipping snarls to war.

Friend-shoring helps our supply/value chains be more transparent and, hopefully, reliable. The United States’ existing relationship with friendly nations enables better communication on trade issues and lets investors from both nations feel comfortable financing new ventures. Further, friend-shoring ensures that the value chain rewards our allies instead of our geopolitical and economic competitors.

Alternatively, nearshoring can spur bilateral trade that will employ Americans in both import- and export-heavy sectors.26 The proximity lowers transportation costs and potential disruptions while simultaneously encouraging cooperation in border regions. For example, Texas exports more than any other state, with Mexico being its primary recipient. Both border regions invest billions in each other’s productive capacity and pursue complementary parts of the value chain (aircraft parts, computer parts, and semiconductors in Texas, and trucks, automotive parts, and finished computers in Mexico).27

Of course, policies that change existing supply chains have some tradeoffs along with their benefits. Our friends and neighbors have the capacity to satisfy much of our demands, but they do not have the same competitive advantages as others. A YETI tumbler made in Sweden or Canada would be much more expensive than one made in Thailand.

Trade Policy in Action

The best example of both friend-shoring and nearshoring is the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). The policy has been largely successful as the two nations are our biggest trading partners—doubling US-Chinese trade—and are our largest export markets.28

Beyond the numeric volume of North American trade, what we import and export between each country illustrates the value chain’s symbiotic nature. Looking at US-Mexico trade numbers, we often trade the same products back and forth (machinery, fuel, vehicles, etc.).29 However, each partner imports and exports specific kinds of goods, enabling each economy to specialize in how they add value. We export machinery like integrated circuits, office machinery, and engines, while we import machinery such as computers, video screens, and broadcasting equipment.30 American intermediate manufacturers, designers, and raw material extractors contribute their expertise to the products we export to Mexico, and the more finished goods we import enable our workforce to utilize their skills. Put simply, we export materials to Mexico, who builds them into productive products, which lets us add value and create more materials we can export.