Report Published January 19, 2023 · 30 minute read

Ten Questions for a New Paid Leave Plan

Curran McSwigan & Anthony Colavito

Takeaways

In the United States, fewer than half of private-sector workers have access to paid medical leave, and only one in four workers has access to paid family leave. Too many workers wake up each morning with the impossible choice of either taking care of their loved ones or losing their jobs.

While many companies and states offer paid leave to workers, access is not universal. As a result, there is an urgent need for federal policymakers to work together to pass a comprehensive paid leave program that helps America’s working families. In the following report, we break down ten questions policymakers should consider when creating a paid leave program and examine what programs or proposals already exist.

No one should have to sacrifice their ability to earn a living to recover from an illness, spend time with their newborn child, or care for an aging parent. Yet too many Americans face the painful choice between losing their livelihood or being unable to care for themselves or their families.

The pandemic revealed deep cracks in our country’s systems of care and just how much Americans are struggling to balance the demands of work and family life.1 Over 70% of mothers with children under 18 are in the workforce, and yet a quarter of new moms have to return to work less than two weeks after giving birth.2 One-in-five Americans provide some form of care to a family member, but without support many are burdened with additional costs and fewer available hours to work at their jobs.3 In the absence of a federal paid family and medical leave program, American families face greater barriers to financial security, the US economy falls short of its potential, and communities of color encounter even bigger hurdles to economic opportunity.4

While an increasing number of states are stepping up to pass legislation that provides paid leave benefits for workers, there is an urgent need for federal policymakers to pursue a comprehensive paid leave program that supports all of America’s working families. In the following report, we look at the state of paid family and medical leave in the United States, break down the decisions policymakers need to consider when constructing a paid leave program, and finally dive deeper into the variety of different paid leave programs and legislative proposals already out there.

Ten Dimensions of a Paid Leave Program

Paid family and medical leave policies have many moving pieces. No two policy proposals are alike, and they may not appear to address the same problems.

When evaluating and designing a program, policymakers need to consider trade-offs, make tough choices, and determine which objectives are most important to them. Specifically, there are ten important questions policymakers should ask themselves when designing a paid leave program—and a range of answers for each. These include:

- Which types of leave are covered?

- How does money get into workers’ pockets?

- Who runs the program?

- How is leave tied to work?

- Who is eligible for leave?

- How much are benefits worth and when do workers receive them?

- How is length of leave determined?

- How is paid leave paid for?

- Does the program offer job protection?

- How does the program interact with other state, local, and employer policies?

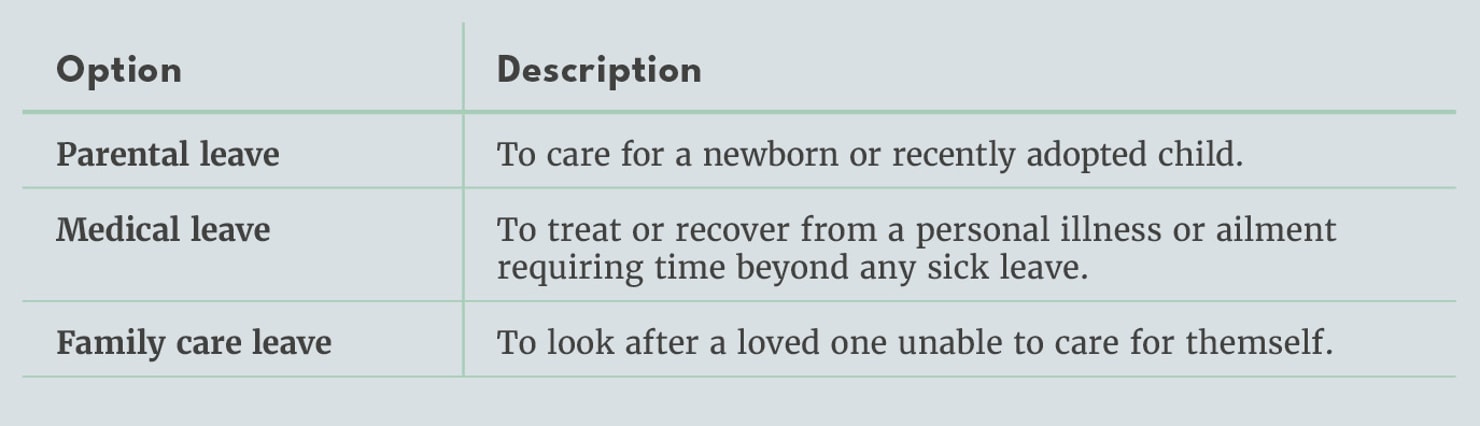

1. Which Types of Leave are Covered?

A national paid leave program can cover various periods of time off from work to accommodate different needs. These types of leave include:

The scope of the program is consequential in determining its cost, its effects on leave takers, and the burden it places on employers, among other things.

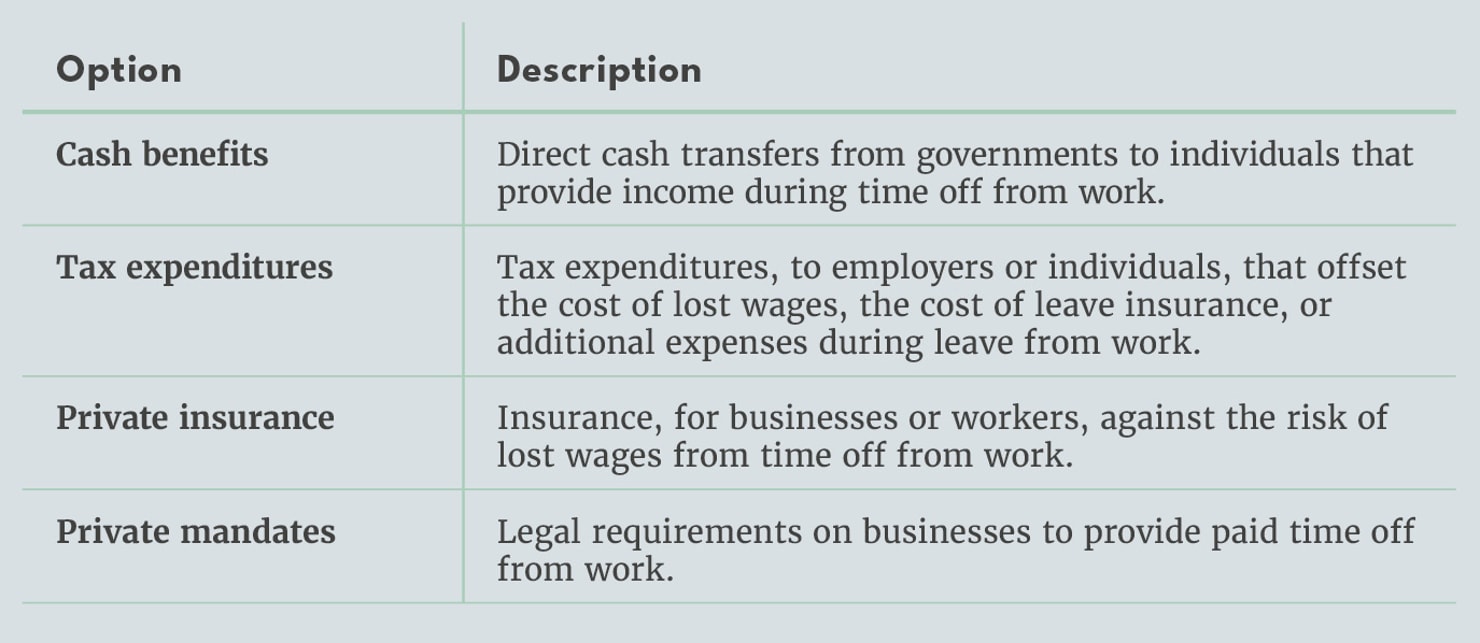

2. How Does Money Get Into Workers’ Pockets?

The federal government can provide or encourage the provision of paid leave through four different methods:

Under the first option, a program could pay out a cash benefit to eligible individuals, similar to how Social Security operates. This approach makes paid leave more accessible to hard-to-reach groups, such as low-income and part-time workers, by providing a portable benefit that can be used across employers. It can help maximize the economic security and mobility provided by a paid leave program but may create larger disincentives to work or be viewed as a new entitlement.

Another option is to subsidize paid leave through the tax system. For example, the government could offer employers tax credits or deductions to offset the cost of buying paid leave insurance or providing paid leave themselves. Or tax credits could go directly to individuals that cover the lost wages and expenses associated with needing to take time off from work. This incentivizes the provision of paid leave and/or helps cushion families’ finances through tax relief or a refundable credit. The drawback is that it does not necessarily guarantee all workers, especially those without a tax burden, will have access to adequate protection.

Individuals and businesses can also purchase paid leave insurance plans on markets established and regulated by the government. In this case, the government can ensure suitable plans are available, such as by mandating minimum standards; prohibiting the exclusion of certain workers from participation, like how it does in the individual health insurance market; and subsidizing the purchase of insurance plans. One of the advantages of this approach is that the government would not have to directly provide paid leave itself. However, the regulation of insurance markets is an important consideration in its own right, and certain businesses and workers, such as part-time and gig workers, may have difficulty participating.

A fourth option is to mandate that private employers provide paid leave. In this scenario, businesses would be legally required to offer paid time off for certain life events, such as the birth or adoption of a child. Public budgets would be unaffected because employers would be paying benefits. However, this could be a burden on businesses and have undesirable employment effects, such as businesses hiring fewer workers.

More than one method may be used when building a paid leave program. For example, a policy might combine private mandates with tax expenditures to ensure paid leave is provided through private sources, such as insurance, without encumbering them with too much of the cost. Another example is New York State, where insurance companies are required to offer paid leave insurance policies and collect state-set premiums and employers are compelled to self-insure or carry a paid leave insurance policy. This system ensures a universal level of coverage without involving the state directly in its provision.

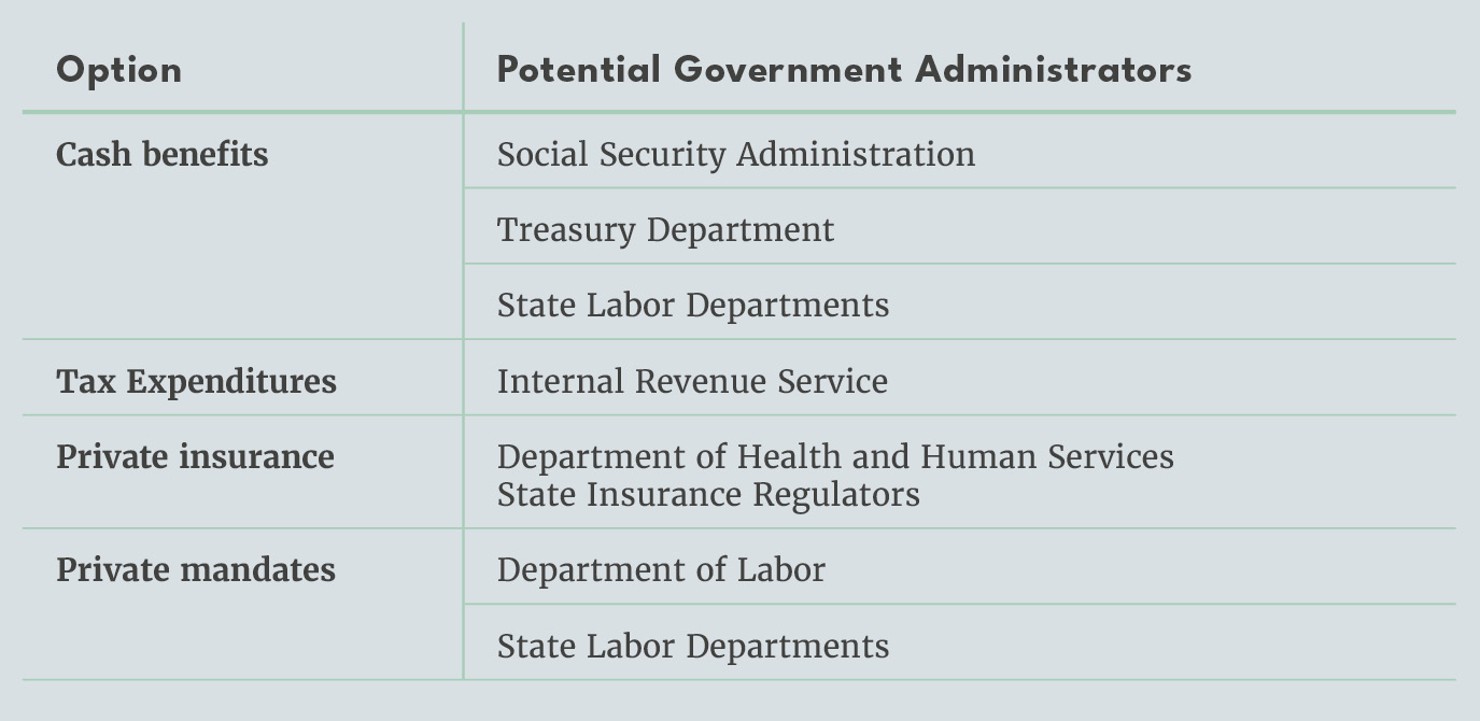

3. Who Runs The Program?

Depending on the method for providing leave, different government agencies can assume responsibility for administering or providing oversight of the program.

If paid leave is a cash benefit, federal or state agencies could feasibly operate the program. At the federal level, the Social Security Administration (SSA) is a potential administrator for a social insurance-like benefit given its experience with distributing retirement and disability benefits. At the state level, state Unemployment Insurance (UI) programs could confer cash for paid leave as some currently do in states with existing programs.5 And if paid leave is incentivized through tax credits, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) would make sense to oversee the program.

A program based on private insurance could be overseen at the federal level by the Department of Health and Human Services or by state insurance regulators. They would establish any insurance exchange and develop policy standards and access requirements.

A legal mandate on businesses to provide paid leave would most likely be administered or regulated by the Department of Labor, which enforces existing labor laws such as the minimum wage, overtime rules, and health and safety regulations. Or it could be left to state agencies for enforcement.

Some approaches involve multiple agencies in the process. For example, under President Biden’s paid leave proposal, grants would have been provided to state paid leave programs, the IRS would have offered tax credits to employers, and the Treasury Department would have operated a residual benefit made available to workers who lacked access to state- or employer-provided paid leave.

4. How is Leave Tied to Work?

Policymakers may find it desirable to tie access to leave benefits to a demonstrated work history. The exact form of these requirements impacts which workers are eligible to receive leave.

If paid leave is to be an earned benefit, some form of work history requirements may be appropriate. For example, a worker could be required to have worked with a specific employer, not just any employer, for a set amount of time before being eligible for leave. Likewise, work history requirements can be adjusted to broaden the scope of coverage to include part-time and gig workers. If policymakers wish to ensure these workers can receive leave benefits, they can expand the scope of documentation that can be used to demonstrate work history and limit the number of hours an employee needs to have worked within a given timeframe to claim leave.

More stringent work history requirements can ensure paid leave is an earned benefit, but they have a trade-off in that more workers can be excluded from eligibility. For example, a 22-year-old mother who recently graduated from college could be excluded from receiving paid parental leave upon the birth of a child due to a lack of long-term work experience.

The way paid leave offerings are tied to work is related to its administrative design. If paid leave is run through employers, there will be a clear work requirement to claim paid leave. If paid leave is administered as a cash or tax benefit, it is possible to adjust the connection between benefits and work history, allowing policymakers to broaden the number of people who can claim leave benefits while increasing the cost of the program.

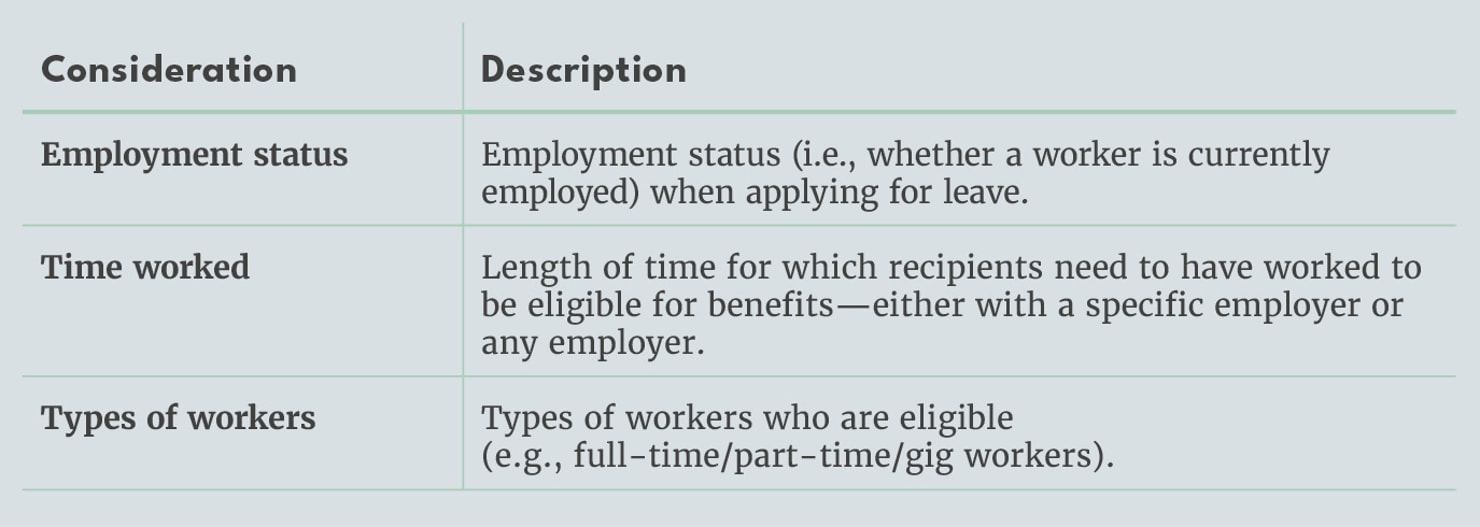

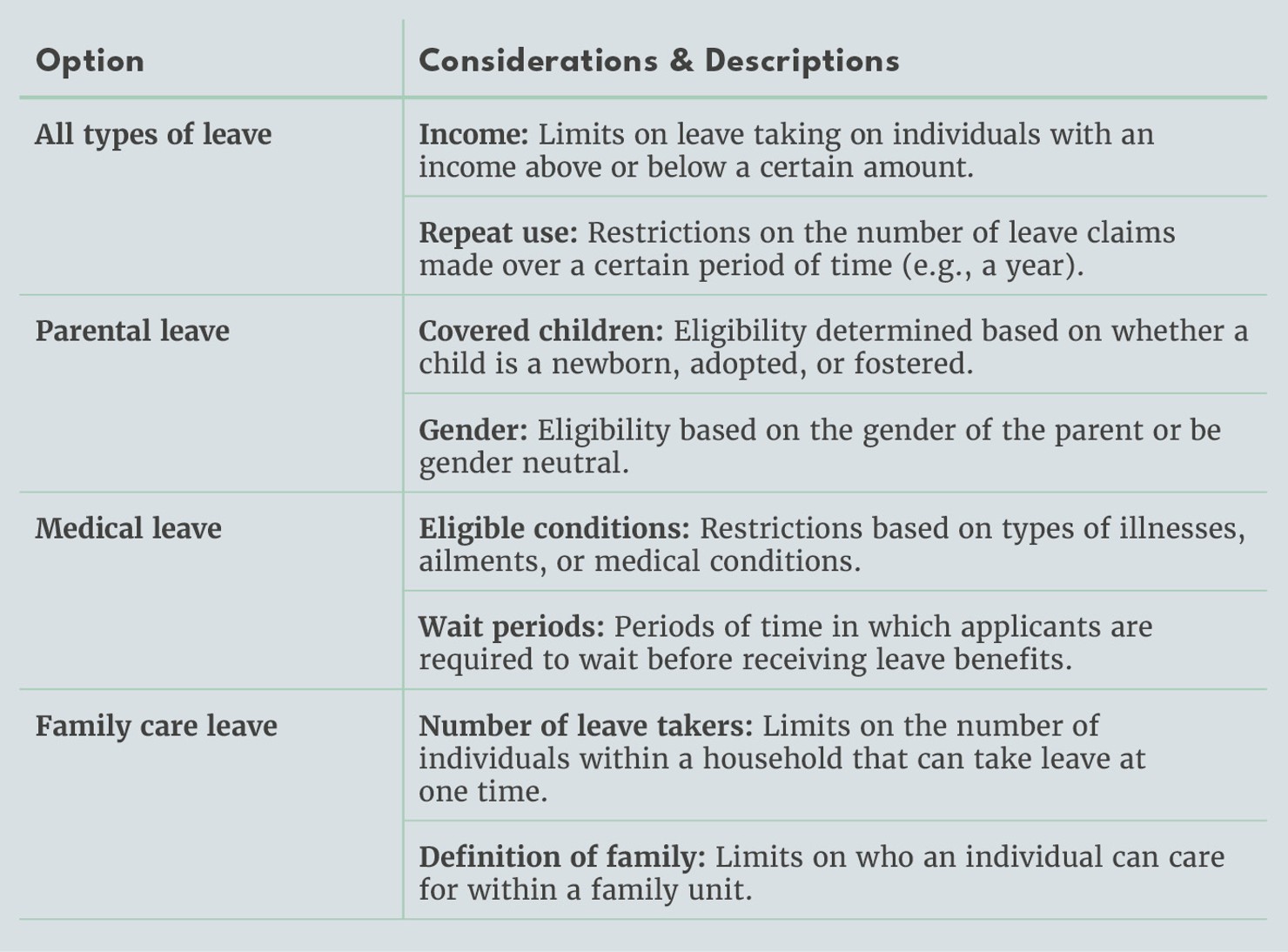

5. Who is Eligible for Leave?

Key to any paid leave program is determining who can access it. Policymakers have several considerations when writing eligibility rules:

For all forms of leave, policymakers may wish to consider whether applicants’ income and past use of leave should limit their claim to paid leave benefits.

With parental leave, eligibility can be based on how a child enters a family and on the gender of the parent claiming the benefit. Variations in these rules affects the number of parents eligible and the program’s impact on gender equity. If parental leave can be split between parents, requirements can be made requiring the father to take some portion of it in order for the household to receive the full benefit.

Medical leave also has its own independent set of eligibility considerations. Policymakers can restrict eligibility to persons afflicted with specific conditions or require a physician to verify that the person cannot work. Additionally, applicants can be required to wait before receiving benefits. For example, if a worker cannot work for medical reasons, their employer could be required to pay sick leave benefits for a certain period before the government begins paying out benefits. Tighter requirements increase the number of persons that may be excluded from the program, but also lessen the potential for abuse.

Family care leave has similar considerations compared to medical leave. The caregiver can be required to demonstrate the person receiving care needs it. Also, limits can be placed on the number of persons within a household receiving family care leave benefits or who an individual can care for within a family unit (e.g., a parent but not an aunt).

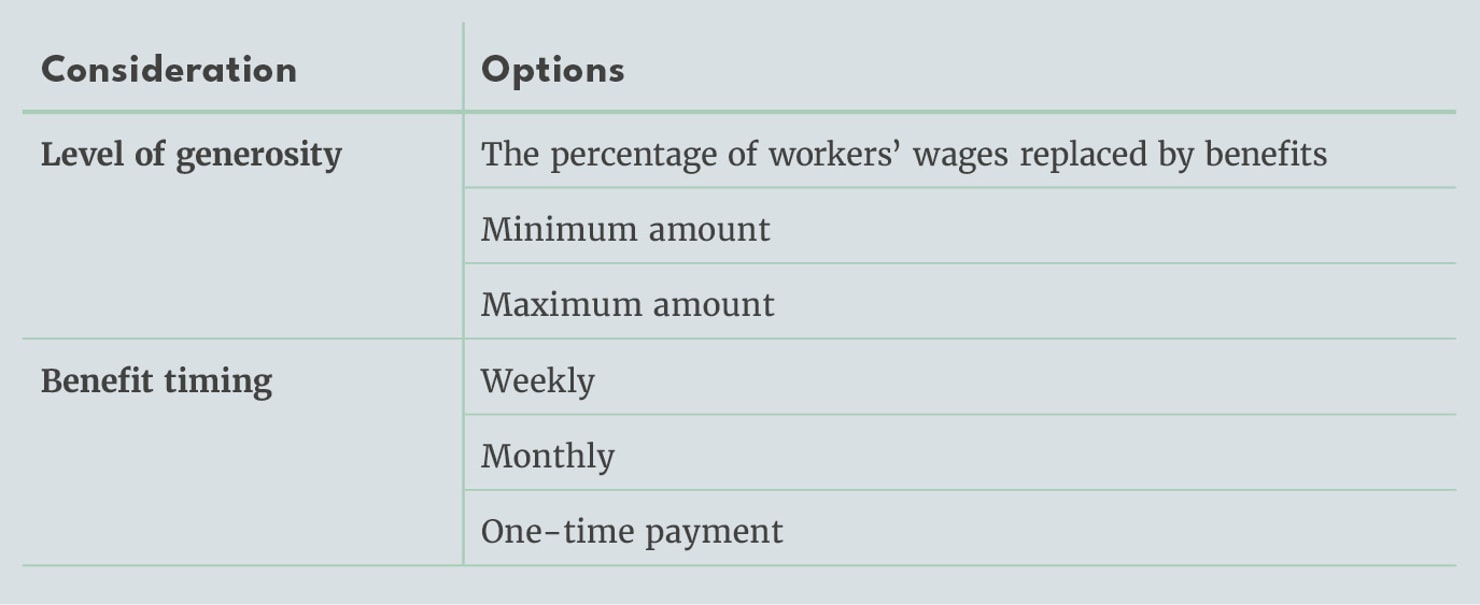

6. How Much are Benefits Worth and When Do Workers Receive Them?

The timing and level of leave benefits can be adjusted along several dimensions:

Any paid leave program will need to decide how much of a worker’s wages should be replaced. This can be done by guaranteeing a percentage of worker’s wages are replaced or designating a minimum and/or maximum benefit. A higher minimum benefit and wage replacement rate can increase the economic security provided by paid leave, but also create a greater budgetary cost and a larger disincentive to return to work. A lower maximum benefit can decrease costs, increase progressivity, and ensure that a larger share of transfers is directed to those who need it most. In addition, a progressive wage replacement structure compensates lower-income workers at higher rates and higher-income workers at lower ones. This is very different than a flat-rate benefit, where workers get the same amount of pay regardless of income.

The timing and length of benefits is also important. Benefits can be distributed in weekly or monthly amounts, or as a one-time payment. They can also be offered for different durations. The longer an individual has access to leave benefits, the greater the length of protection. However, longer leave times come with greater costs to the public, businesses, and even workers themselves as they become detached from the labor force. In some European cases, policymakers who sought to provide benefits for longer did so at lower benefit levels. This approach to setting benefit durations can ensure protection is available for longer but minimize costs to both budgets and the labor force.

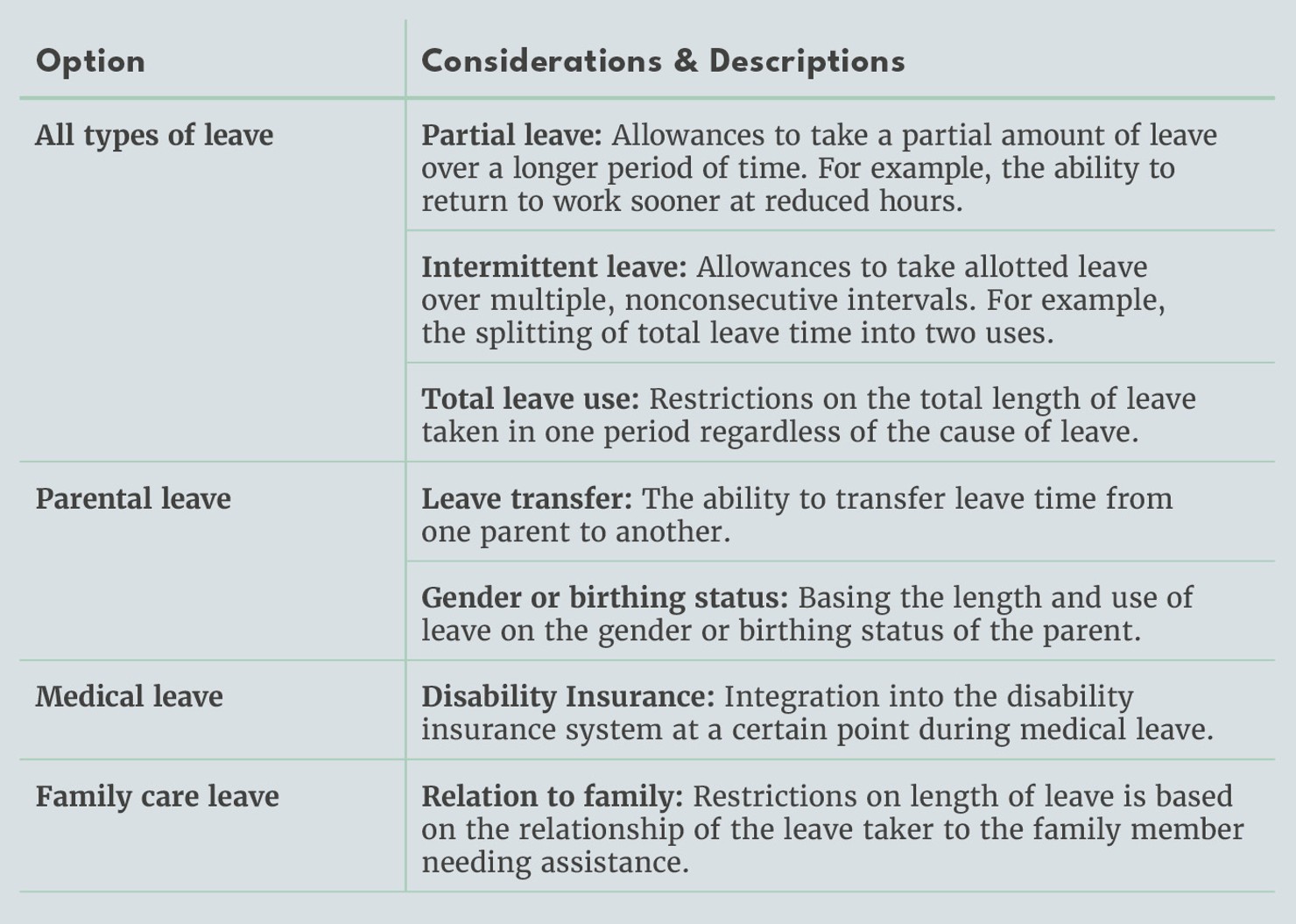

7. How is Length of Leave Determined?

Policymakers must also decide how long their leave program will be. The length of leave they decide to offer to workers may be impacted by the type of leave taken and who is taking leave.

The length of time offered in a paid leave program may be impacted by various considerations to accommodate different worker needs. For example, a mother may receive longer leave to care for a young child than they would to care for an aging parent, while certain paid leave systems may allow new fathers to transfer a certain amount of parental leave to mothers. These factors can play a role in the amount of leave that is accessible to workers.

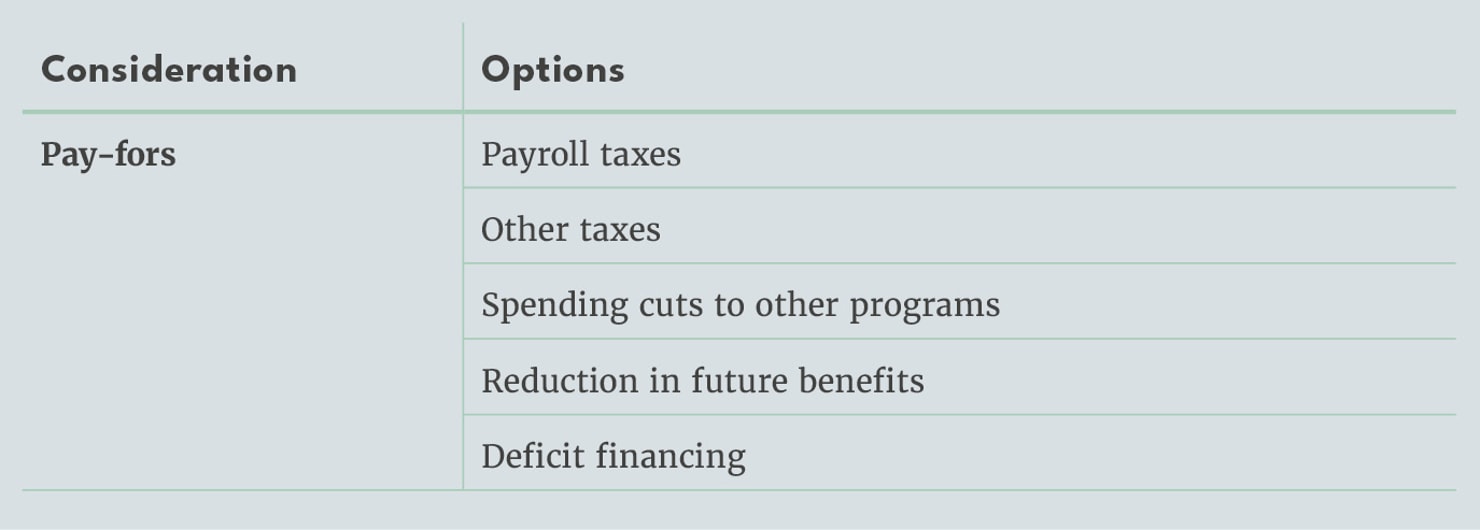

8. How is Paid Leave Paid For?

Once policymakers decide how much they want to spend on paid leave, they must determine how to pay for it. Their options include:

Paid leave can be financed through new or additional taxes, cost savings from cuts or reforms to other programs, or deficit spending. And these funds can run through a trust fund, be paid out of general revenue, or flow from states or employers. For example, to solidify a paid leave program’s connection to work, a separate trust fund for payroll taxes can be created. Then, paid leave benefits can be drawn from this fund. In this way, benefits are tied to contributions.

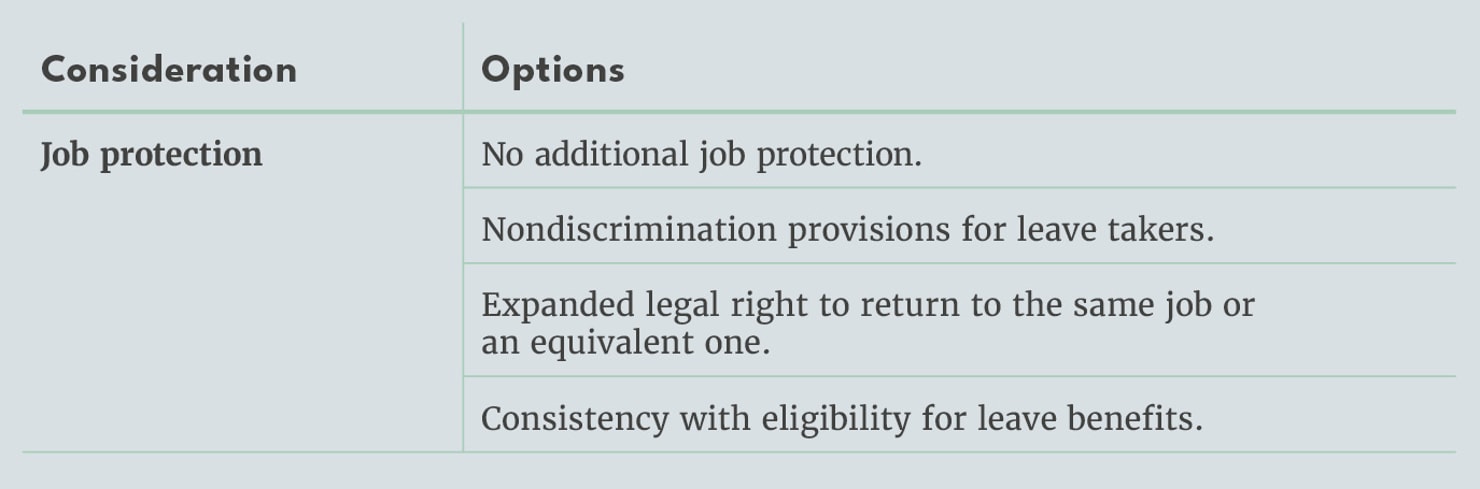

9. Does the Program Offer Job Protection?

Aside from determining benefit levels, duration, and eligibility, any paid leave program must determine whether or not to expand job protection—the legal right currently under the FMLA to return to the job one is taking leave from. Currently, only about 50% of workers are eligible under FMLA to return to their job or an equivalent one after periods of leave.6 Policymakers have the option of creating different levels of job protection. They can implement provisions that prohibit the firing of employees who take or desire to take paid leave. Or they can create a legal right to return to their job or an equivalent one after a period of leave. These protections differ in the level of protection they offer employees and the burdens they place on employers.

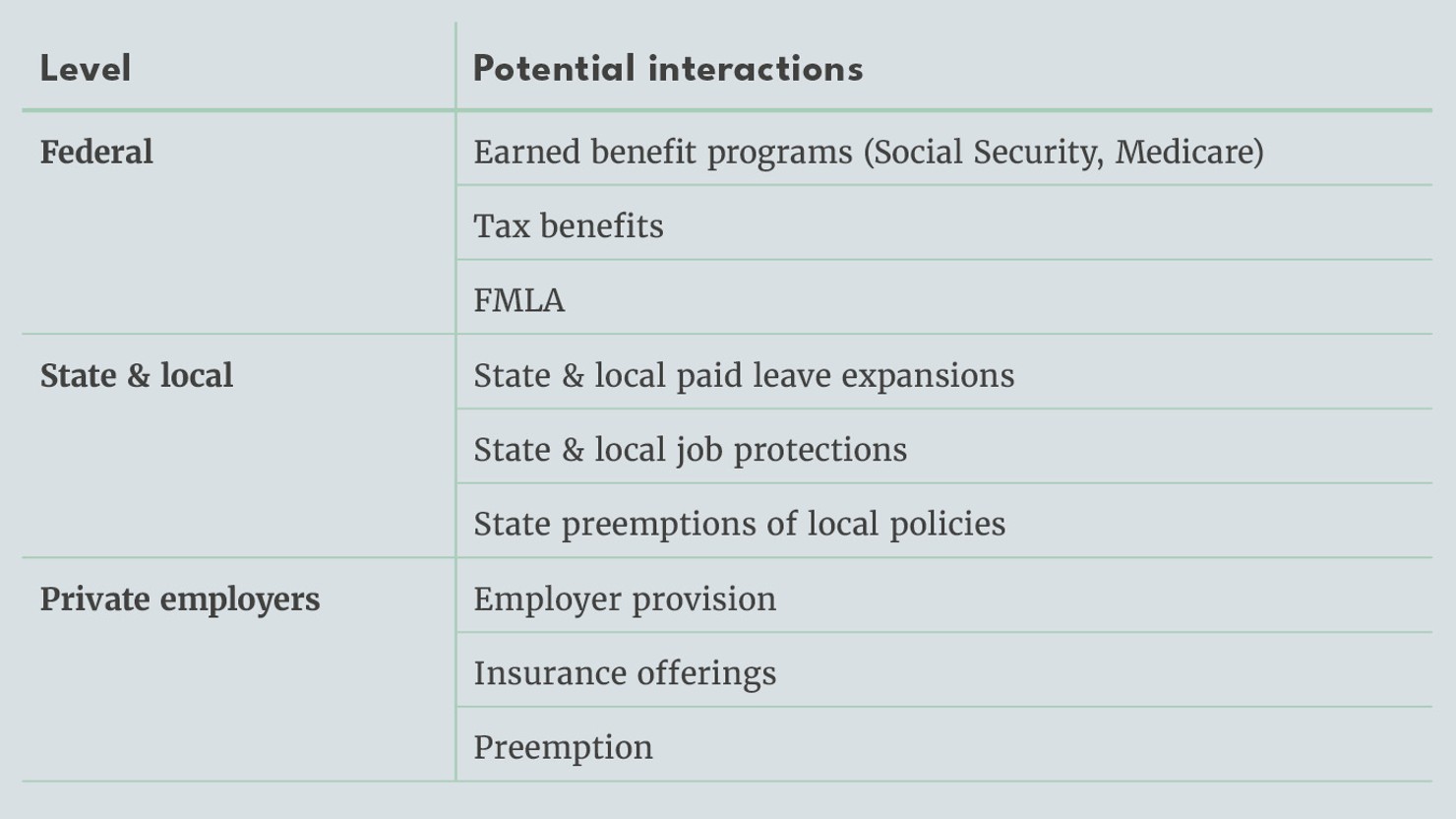

10. How Does the Program Interact with Other Federal, State, and Employer Policies?

Once policymakers have settled on a framework for their leave program, they must take care to see how it interacts with other federal, state, local, and employer policies.

There are many points at which a federal paid leave program can interact with other government and employer policies. For example, a federal paid leave policy could preempt the state, local, or private provision of leave benefits, or it can be provided in addition to them. Separately, if paid leave is provided as a federal cash benefit, the timing of those benefits could align with the duration of job protection under the FMLA or other state laws, or it could last for shorter or longer periods of time. Such cash benefits can also be included or excluded in the methods for determining eligibility of other programs, such as Social Security. In addition, the paid leave policies may require changes or expansions to existing unpaid benefits under FMLA.

The decision points above offer a wide-ranging, but by no means exclusive, list for policymakers to consider when building a paid leave program. Numerous other issues are likely to arise. For example, how will the new program be most effectively implemented once it is passed? And what should monitoring the program’s success look like? Once a policy is passed, there are certain to be other important considerations both during and after its rollout.

Existing Paid Leave Programs

Based on the decision points above, it is clear there are many ways to think about and put together a paid leave program. Other countries implemented paid leave systems decades ago, while some areas in the United States are only more recently stepping up to get these benefits to workers. Many federal policymakers are also bringing their own ideas to the table on what a PFML program in the United States might look like. Below we explore the existing and proposed paid leave programs to date.

Employers

Currently, one-in-four employees have access to paid family leave benefits (such as for the birth of a child) through their employer and less than half have access to paid personal medical leave (such as for cancer treatment or inpatient medical care).7 Paid leave is also an employee benefit that helps higher-income workers the most—the top quarter of wage earners are nearly three times more likely to have paid family leave offered to them than those in the bottom quarter of earners.8 It also disproportionately leaves behind communities of color—white workers are more likely to have access to paid family and medical leave than their Black and Hispanic peers.9 The dashboard below displays how access to paid leave varies greatly among income levels, industry sectors, regions, and type of employment.

States

In the absence of a federal policy on paid family and medical leave, some states have passed legislation implementing their own PFML programs. Currently, California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Washington, Colorado, Oregon, and the District of Columbia offer paid medical and family leave to workers, while Maryland and Delaware have passed legislation to establish their own programs, but they are not yet stood up.10

Amid these efforts, there are clear limitations to what progress can be made at the state and local level. Paid family leave legislation passed in Vermont was ultimately vetoed by the state’s governor. In 2021, North Dakota passed a bill banning cities or counties from implementing their own paid family leave programs.11

The first group of states to implement PFML programs, including California and New York, built them as extensions of existing state disability insurance programs. As a result, family leave and medical leave benefits are considered separate from one another, with the number of weeks designated for medical leave being different than the number of weeks set aside for family leave.12 Newer programs have departed from this format, instead designating a set amount of leave workers can use over the course of a year, with employees deciding how to use that time.13 In addition, some states like New Hampshire, Vermont, and Virginia have pursued a voluntary model, where paid family leave is encouraged through private insurance that employers can choose to purchase for their workers.14 While there are differences in the administration and implementation of programs across states, there are also a lot of shared characteristics. Most are financed by a payroll tax split between employers and employees, include a progressive wage replacement rate, and stipulate requirements for how long a worker has been employed prior to receiving the benefits.15

For a further state-by-state breakdown of paid family leave programs, see the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Appendix on State Paid Family Leave Programs.

Federal

At the federal level, the United States does not have a paid leave requirement. However, the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) offers eligible employees the opportunity to take up to 12 unpaid weeks off during the course of a year for certain family and medical reasons.16 It should be noted that FMLA is limited in scope, only covering those working for government agencies, elementary and secondary schools, as well as private sector employers with 50 or more employees within a 75-mile radius of their worksite.17 In order to be eligible for unpaid leave, a worker must also have been with their employer for at least a year and have worked a minimum of 1,250 hours in the last 12 months.

These requirements mean less than 60% of workers in the United States are eligible to take time off through FMLA, and half of those who are eligible don’t end up taking any leave because they can’t afford to do so.18 Plus, even when workers do take advantage of FMLA, one-third end up cutting their time off short due to financial challenges.19

In 2017, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) created a new employer tax credit for businesses that provide certain forms of paid leave. Under current law, it is set to expire in 2025.20

Spotlight: International Comparisons

Every country in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) but the United States has a nationwide paid parental leave policy and most offer some form of caregiving leave in addition to medical leave.21 In these countries, parental leave benefits are usually broken down into three buckets: maternity, paternity, or broader parental leave. Maternity leave is typically the most robust, with all countries but the United States offering an average of 17 weeks of paid time off. Paternity leave is offered in 70% of OECD countries, but time off averages at just two weeks.22 However, a majority of countries also offer paid parental leave that extends beyond designated maternity or paternity leave, although it is usually paid out at a lower rate.23

In addition, job protection and flexibility in leave policies, such as allowing for part-time work arrangements and the transfer of time-off between parents, is a key part of most of these countries’ parental leave programs. This ensures that new parents can remain attached to the labor force while also maintaining a strong work-life balance.24

Across the OECD, parental and caregiving leave programs are typically paid for using social insurance funds, which contain contributions from employers, workers, and governments.25 While medical leave is also offered in most of these countries, it is different in that it is most often funded first by employer designated benefits, with any additional leave time being paid for through broader social insurance funds.26

While FMLA in the United States applies only to larger companies, most OECD countries do not share the same exemption for businesses with just a few employees. However, several countries have sought to enact policies that address the disproportionate impact paid family leave may have on small businesses. The UK reimburses small business owners 103% of parental leave payments they make to employees, compared to 92% for larger companies, while France offers tax credits for workplaces that have family-friendly policies.27

For a further breakdown of the key components of paid leave systems in OECD countries, see Appendix B in the Congressional Research Service’s Report on Paid Family and Medical Leave.

Federal Legislative Proposals

Paid leave proposals can be found across the political spectrum. While common themes exist, there is no single set of answers to the question of how to provide paid leave to all Americans. On both the left and right, policy designs vary greatly based on structure, scale, and reach. The following list of proposals elucidate the current policy debate and showcase the most prominent proposals, reflecting the diversity of the options available to policymakers.

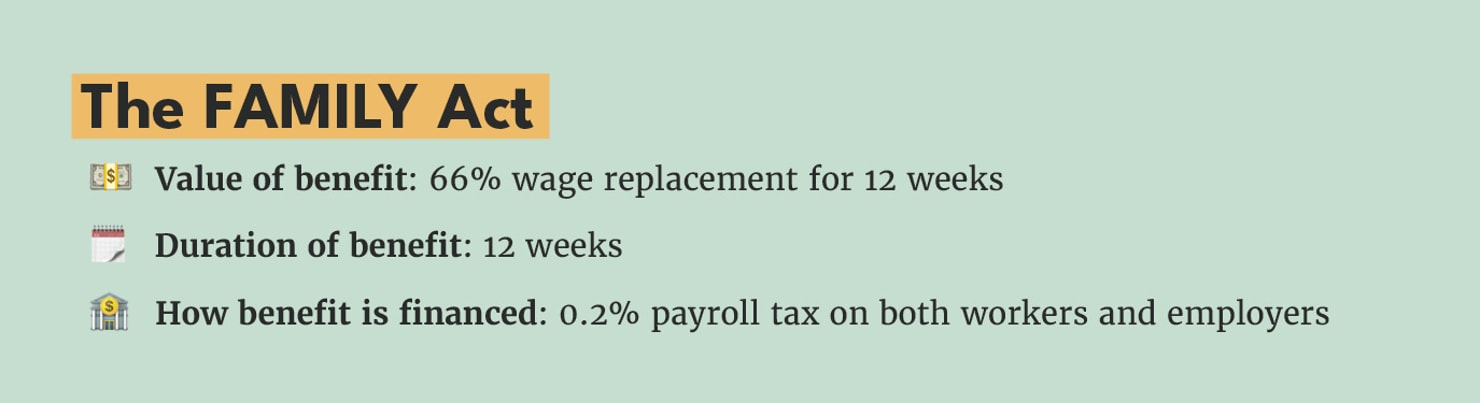

The FAMILY Act (Sen. Gillibrand/Rep. DeLauro)

For Democrats, the most prominent paid leave proposal out there is the FAMILY Act, which has been introduced in several Congresses by Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY). She, alongside Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), reintroduced the bill in early 2021. Under this version of the FAMILY Act, eligible workers would receive around two-thirds of their average monthly wages for 12 weeks, with a maximum replacement of $4,000 per month, adjusted annually to account for changes in the national average wage index.28 Unlike FMLA, the FAMILY Act would cover part-time and self-employed workers, as well as employees of small businesses. To finance the benefit, the bill proposes a 0.2% payroll tax on both workers and employers.29 This benefit covers parental, medical, and family care leave.

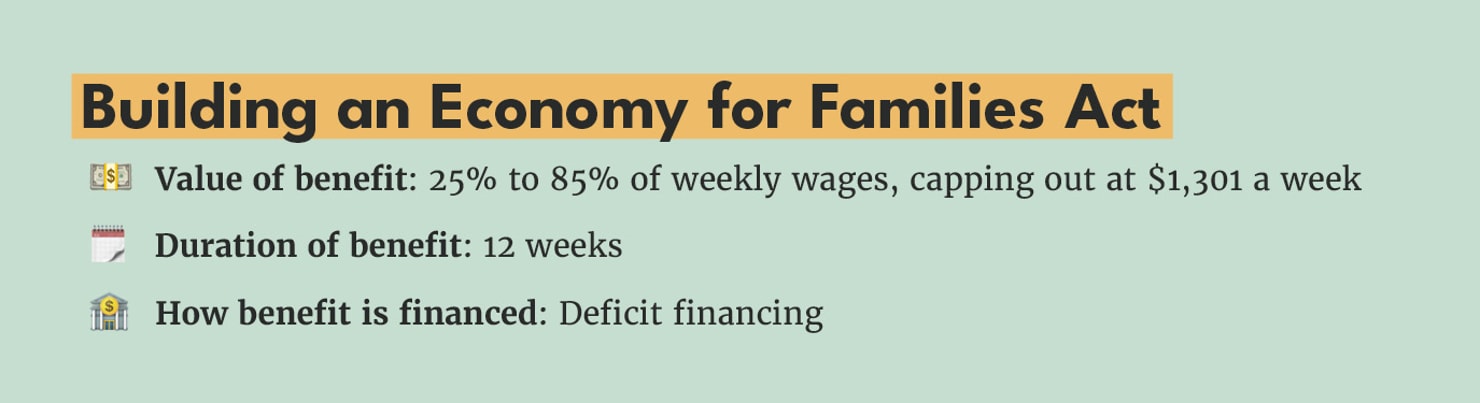

Building an Economy for Families Act and Build Back Better (Rep. Neal)

Introduced by Representative Richard Neal (D-MA), the Building an Economy for Families Act (BEFA) is a broad piece of social legislation aiming to guarantee a list of items, including access to childcare and a PFML system.30 The paid family leave portion of the bill aims to ensure all workers have access to 12 weeks of PFML, which would encompass parental, medical, and caregiving leave. It would be provided either through employer benefits, state programs, or a new federal entitlement program administered by the Department of Treasury and funded through appropriations.31 The legislation would provide workers with up to 85% of their weekly wages, with the wage replacement falling as income rises. The benefit caps out at $1,301 a week, adjusted annually to account for changes in the national average wage index.32 Of note, it would only be available to those who don’t already have access to paid leave through their state or employer.33 Leave is limited to workers who worked at some point in the prior two years and was working in the 30 days prior to taking leave.34

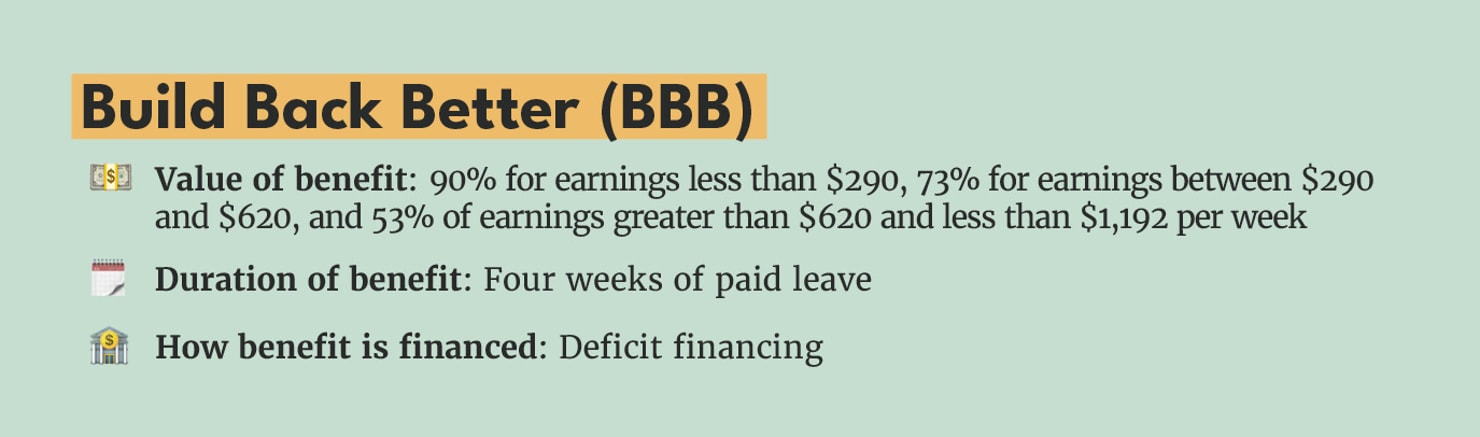

A version of Neal’s bill was included in the House-passed version of the Build Back Better (BBB) Act. Under the BBB version there were only four weeks of paid leave, tighter work history requirements, higher wage replacement rates, and a lower maximum benefit amount.35

The New Parents Act (Sens. Rubio & Romney)

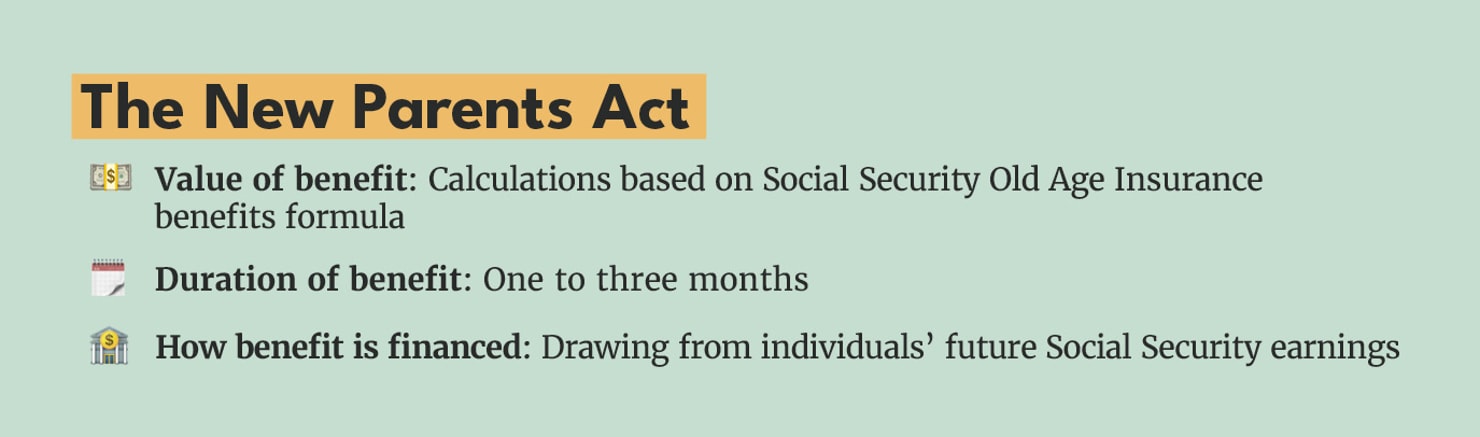

Introduced by Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Mitt Romney (R-UT) in 2021, the New Parents Act is one of the main paid leave legislative proposals that has been put forth by Republicans. The legislation would allow new parents to borrow against their future Social Security earnings to finance up to three months of parental leave only.36 The value of the monthly benefit would be determined by parents’ prior earnings according to the Social Security Old Age Insurance benefits formula, with the wage replacement rate being highest for lower income families and falling as income increases.37

The CRADLE Act (Sens. Lee & Ernst)

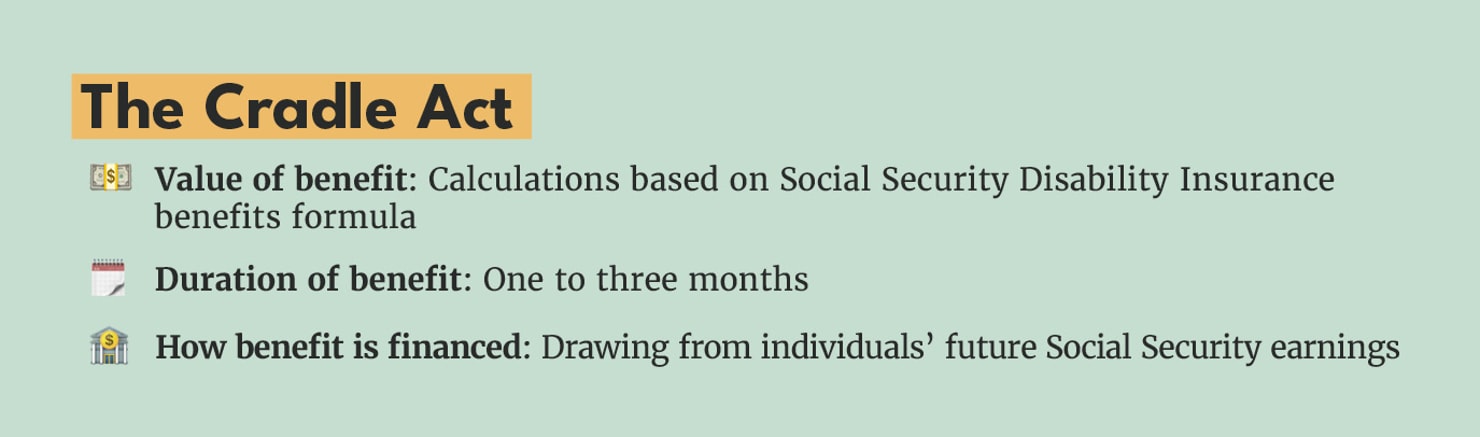

The CRADLE Act was introduced by Republican Senators Mike Lee (R-UT) and Joni Ernst (R-IA) in 2019. The legislation is similar to the New Parents Act in that it also allows new parents to borrow against their future Social Security earnings to finance paid leave.38 But unlike the FAMILY Act and New Parents Act, it caps the total amount of benefits workers can receive. So, while legislation like the FAMILY Act and the New Parents Act allows parents to collect other types of benefits in addition to those they receive through the federal program, like paid leave from their employer, the CRADLE Act sets a cap on the amount of benefit an individual can receive altogether. As such, if a new parent were to receive other parental leave paid benefits, the CRADLE Act benefits would be reduced by the difference.39

Trump Administration Budget Proposal

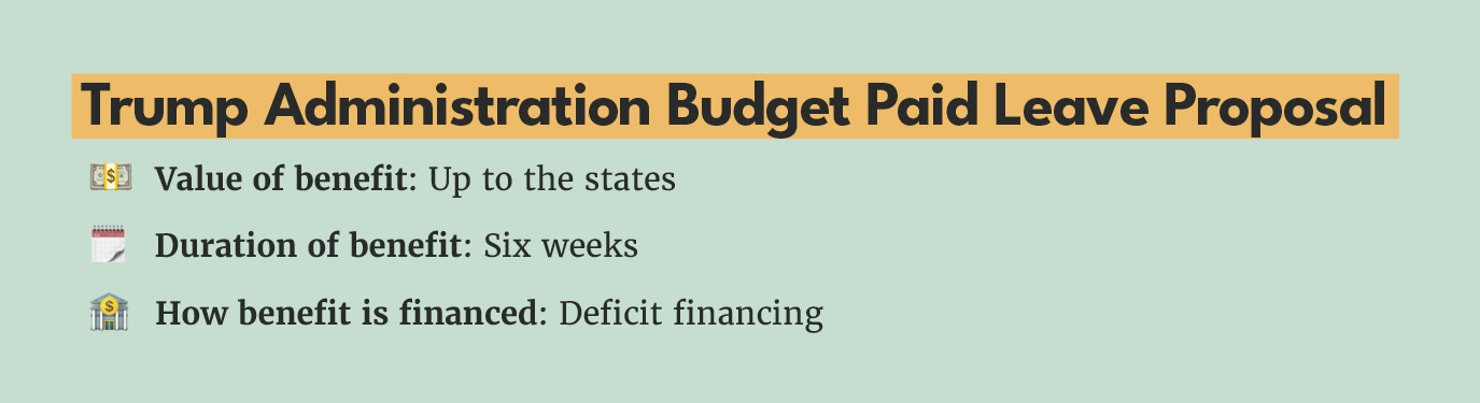

In all four of their budget proposals, the Trump Administration proposed requiring states to provide a minimum of six weeks of paid leave to parents through their Unemployment Insurance (UI) systems.40 Who is eligible, benefit levels, and financing of the system would remain up to the states. The federal government would fund start-up and administrative costs but provide none of the money for leave benefits themselves. States would be required to draw leave benefits from their UI trust funds as they currently do for regular unemployment benefits.41

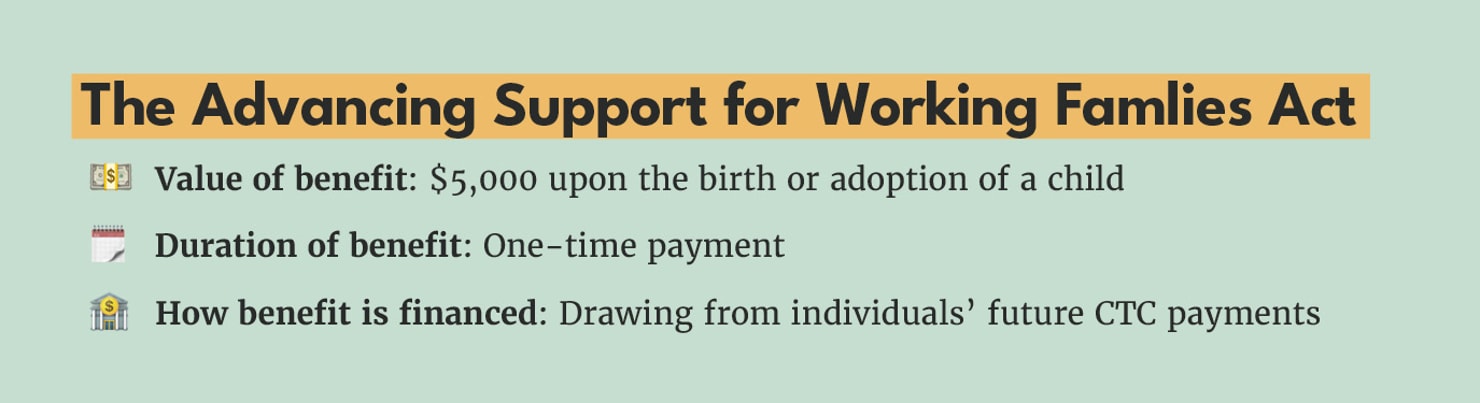

The Advancing Support for Working Families Act (Sens. Cassidy & Sinema)

Senators Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Krysten Sinema (I-AZ) unveiled a bipartisan bill to provide paid parental leave in 2019. Under the Advancing Support for Working Families Act, parents can opt to receive an advancement of up to $5,000 from the Child Tax Credit (CTC) upon the birth or adoption of a child.42 If parents choose to claim the benefit, they will pay it back by having their CTC adjusted downwards by $500 every year for the next ten years. Families without enough earnings to qualify for the full CTC can receive an advanced CTC equal to the lesser of either $5,000 or 25% of their annual income from the previous year. They would then receive a downwards-adjusted CTC for the next 15 years.43

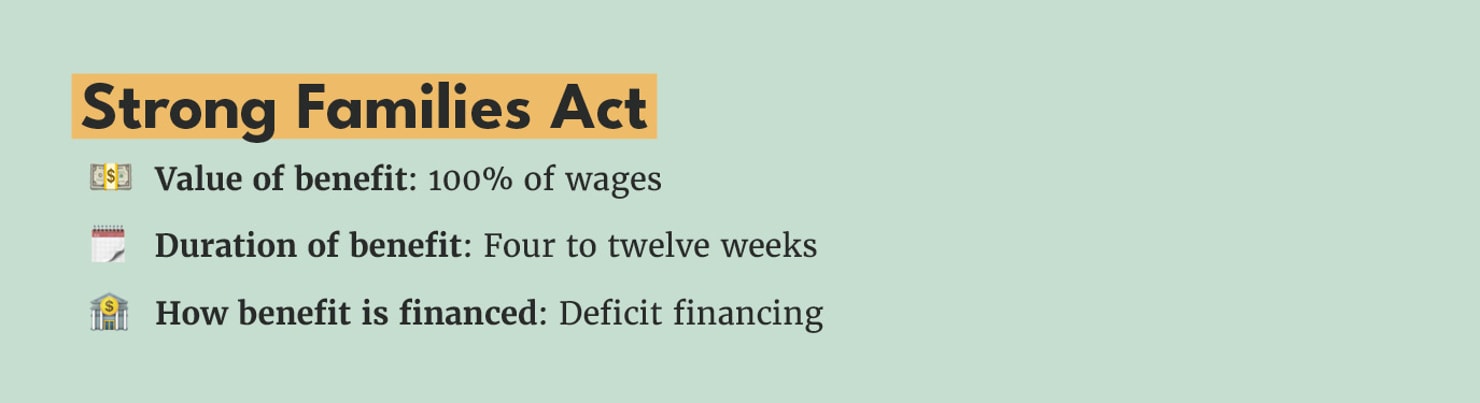

The Strong Families Act (Sens. Fischer & King/Reps. Kelly & Sewell)

In 2017, Senators Debb Fischer (R-NE) and Angus King (I-ME) and Representatives Mike Kelly (R-PA) and Terri Sewell (D-AL) proposed a bill to provide tax credits to employers offering paid leave.44 The Strong Families Act would allow employers who voluntarily offer at least two weeks of paid leave to claim a nonrefundable tax credit worth up to 25% of cash paid for each hour of leave offered to employees earning less than $78,000 annually.45 Employers would only be allowed to claim the credit for up to 12 weeks of paid leave per qualified employee up to a maximum credit of $3,000 per employee. The credit is available for workers already eligible for FMLA leave and some additional workers who receive qualified periods of leave, including part-time workers. Employers of part-time employees can claim a pro-rated portion of the credit. For example, if someone works 20 hours a week, their employer could offer one week of paid leave to qualify for the tax credit. This bill was folded into the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 and was originally set to expire in 2019. It is currently set to expire in 2025 after having been extended twice, once for a year in 2019 and again for five years at the end of 2020.46

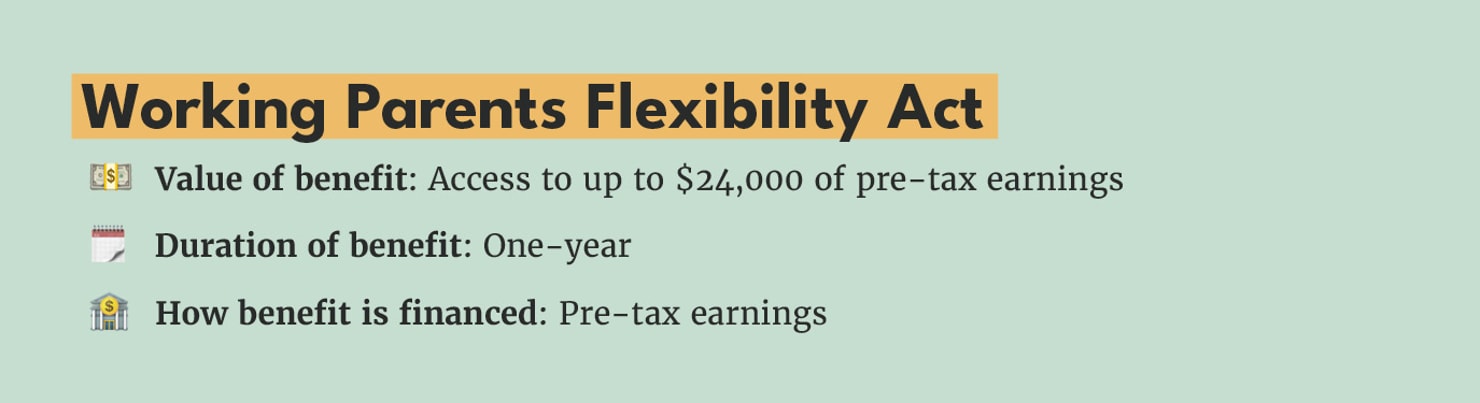

Working Parents Flexibility Act (Savings Accounts) (Reps. Katko & then-Rep. Sinema)

During the 115th Congress, Representative John Katko (R-NY) and then Representative Kyrsten Sinema (I-AZ) introduced the Working Parents Flexibility Act of 2017, which would allow workers to divert some of their pre-tax earnings into a parental leave savings account.47 Under the bill, eligible workers can withdraw money from this pre-tax account at any point during the year after birth, allowing workers to pay for expenses associated with the birth of a child or be able to afford to take time off without losing income. Total contributions across all years would be capped at $24,000, and no one making over $250,000 is eligible to deposit funds into an account.48 The legislation was reintroduced in 2019.

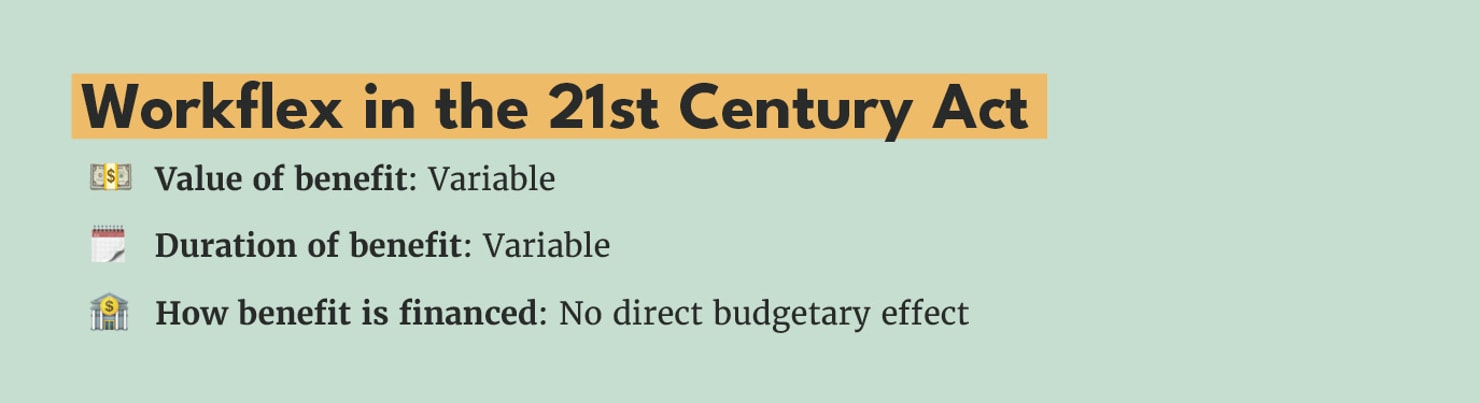

Workflex in the 21st Century Act (Reps. Miller-Meeks & Virginia Foxx)

In the 117th Congress, Representatives Mariannette Miller-Meeks (R-IA) and Virginia Foxx (R-NC) introduced the Workflex in the 21st Century Act, a bill which would allow employers who offer some sort of paid leave and flexible work arrangement options to be exempt from state and local leave laws. Specifically, the bill amends the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, known as ERISA, to create completely voluntary Qualified Flexible Work Arrangement (QFWA) plans. These plans allow employers to offer paid leave and several flexible work arrangements to their employees. If an employer does decide to offer the QFWA plans, the plan must include paid leave and some type of flexible work arrangement.49 But in exchange, the employers who offer these plans would then be exempt from certain state and local leave laws, which may be more or less generous or have other requirements than employer plans.

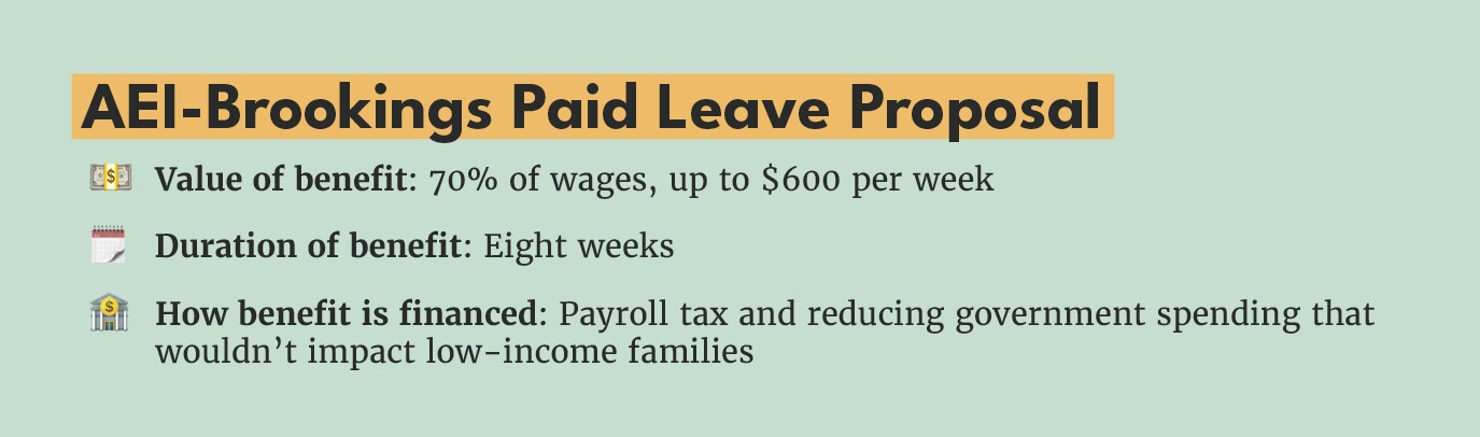

AEI-Brookings Proposal

Researchers in the joint working group put together by think tanks American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and Brookings Institution published a comprehensive evaluation on the need for paid leave in the United States alongside what they believe should be included in a federal paid parental leave program. They argue any program should be tied to work, but that job protections must extend beyond what is currently offered in FMLA. They also propose that new parents should be eligible for up to eight weeks of paid leave, receiving up to 70% of their weekly wages, with a maximum replacement of $600 per week. The group suggested the program should be paid for through both a payroll tax hike and expenditure cuts that would not negatively impact low-income families, although there was some disagreement on how exactly this would be executed.50

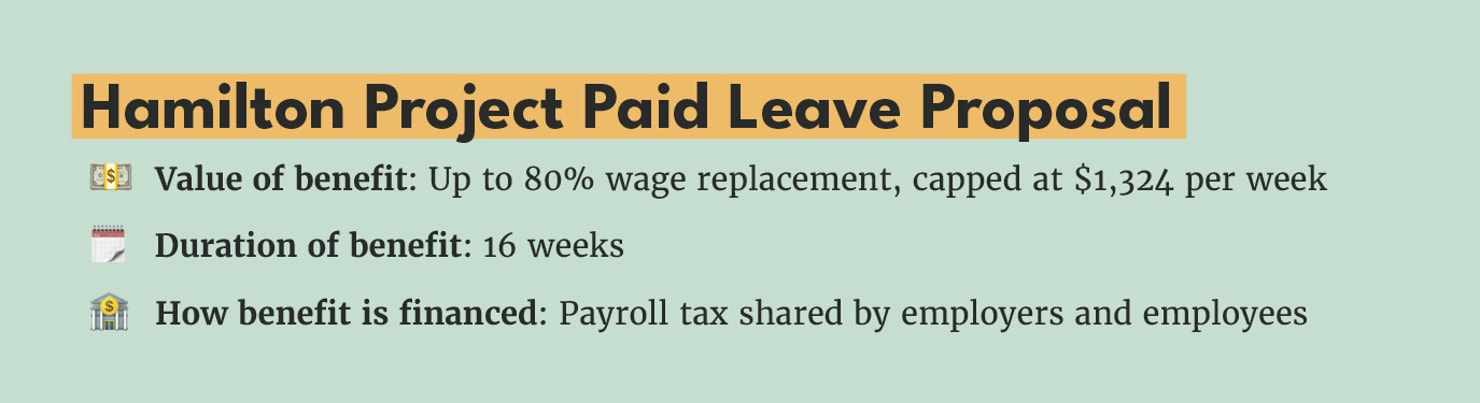

Hamilton Project Proposal

In 2021, The Hamilton Project published their own proposal for a federal PFML program, which would grant up to 16 weeks of parental leave per child, 12 weeks for medical leave and six weeks for caregiving leave, with any individual maxing out at 16 weeks of any type of leave per year.51 The benefit amount would vary based on income, with lower-income workers facing a higher wage-replacement rate at around 80% and falling as earnings rise, and cap out at $1,324 per week. The wage replacement rates would also be tied to inflation.52 The proposal would be paid for through a payroll tax to be split equally between employees and employers, which would exclude self-employed workers from being eligible. But unlike FMLA, which requires an attachment to a specific employer for workers to be eligible, this proposal suggests workers must only earn wages in at least 39 of the preceding 52 weeks before applying, but it does not matter if it is for the same employer.53

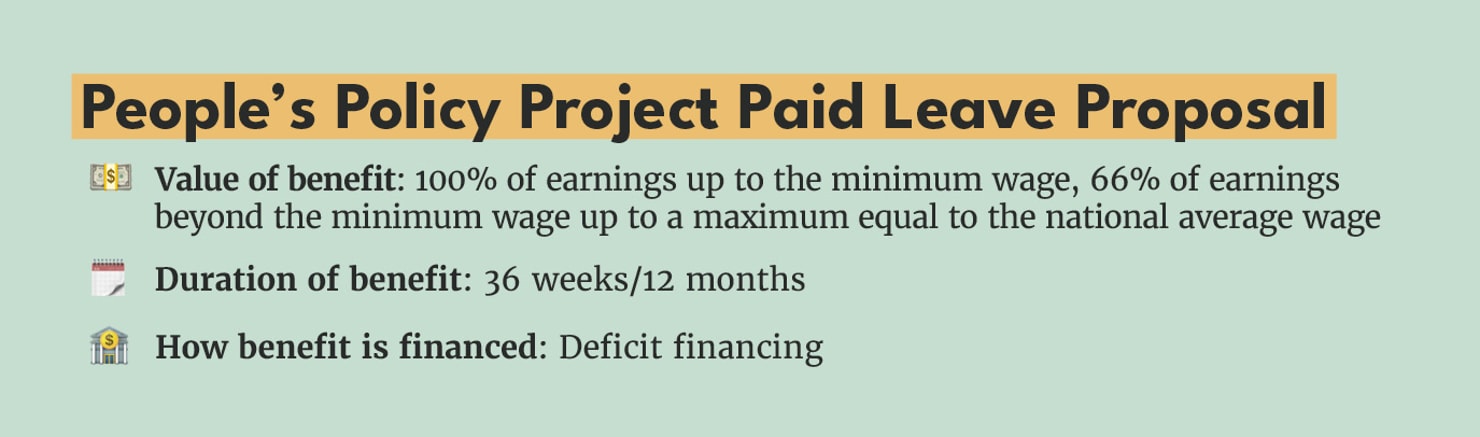

People’s Policy Project Proposal

Under the People’s Policy Project’s Leisure Agenda, workers would be eligible for 36 weeks of paid parental leave and 12 months of paid medical leave.54 Upon the birth or adoption of a child, each of their parents would be eligible for 18 weeks of paid leave, of which they would be permitted to transfer 14 of the 18 weeks to the other parent. Where there is only one custodial parent, they will be eligible for the full 36 weeks of paid leave. Individuals on leave will receive benefits equal to 100% of earnings up to the minimum wage and 66% of earnings beyond the minimum wage. The maximum benefit would be equal to the national average wage.

If a worker becomes sick and cannot work for an extended period, they will become eligible for 12 months of paid medical leave and receive benefits equal to what they would receive if they took paid parental leave. Employers would pay for the first month of leave while the government would cover the rest, similar to how many OECD countries already administer medical leave. If a worker is still unable to work after 12 months, they would be folded into the Disability Insurance system.

Conclusion

The need for a federal paid family and medical leave program becomes more important with each passing day. At this juncture, bipartisan progress on at least some components of a robust federal paid leave program may be within reach. It is critical that policymakers on both sides of the aisle rise to the occasion and work together to push for policies that will ensure every worker is afforded the right to earn a good living while also being able to take care of themselves and their loved ones.