Report Published September 9, 2020 · 26 minute read

Weakened Encryption: The Threat to America’s National Security

Mieke Eoyang & Michael Garcia

Takeaways

For years, law enforcement officials have warned that, because of encryption, criminals can hide their communications and acts, causing law enforcement to struggle to decrypt data during their investigation—a challenge commonly referred to as “going dark.” They called on technology companies to build a process, like a “master key,” to enable law enforcement to unlock encrypted communications. While this may seem like a tempting idea, it would have grave implications for our national security. As more and more of our communications move online, users seek out encrypted services to protect their privacy. Unlike telephonic communications, and despite repeated requests by law enforcement to do so, Congress has not required internet communications platforms to give law enforcement access to intercept user communications or access stored communications. In this paper, we assess the national security risks to a requirement to provide that master key (referred to throughout as “exceptional” or “backdoor” access) to encrypted communications and propose alternative approaches to address online harms.

In short, requiring exceptional access to encrypted technologies would undermine national security by:

- Weakening protections for the information that the national security community relies upon, especially as it flows over foreign networks.

- Creating a vulnerability in encrypted communications that could be accessed by foreign adversaries.

- Encouraging other countries to require tech and internet companies to provide equivalent access to communications within their boundaries.

This does not mean that the internet should be a lawless zone. Law enforcement and the private sector can and should cooperate in addressing crimes on the internet and can do so without undermining a protection as fundamental as encryption.

How Encryption Works

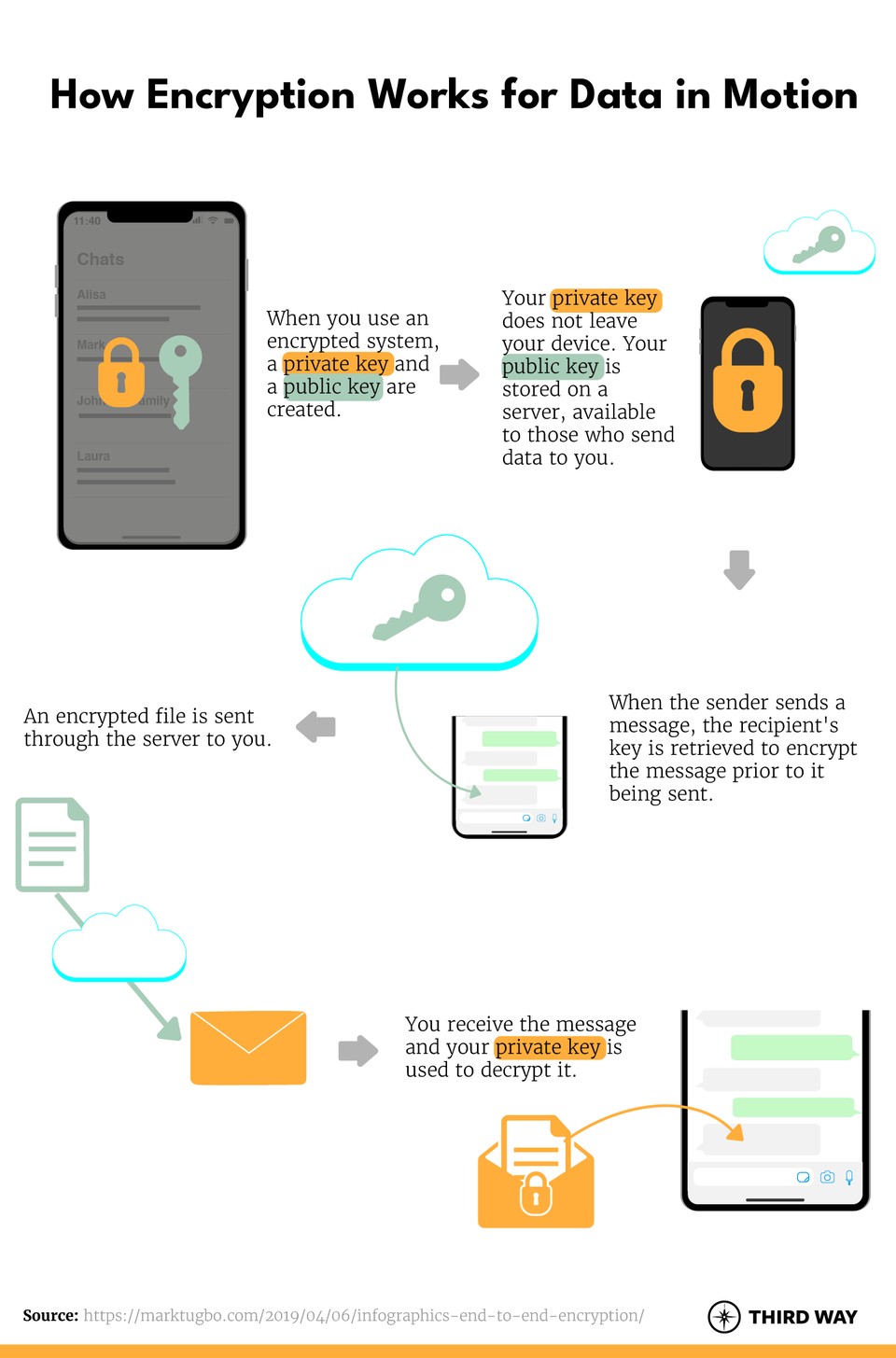

Two forms of encryption generally exist that protect two types of data: “data in motion” and “data at rest.”1Encryption protecting data in motion (e.g., sending text messages) is a method of encoding information to ensure that only the sender and the recipient of a piece of information can view and read the information. If another party, such as the service provider or app developer, tries to read the information while it is in transit it will appear as a random collection of letters and numbers. This is often referred to as end-to-end encryption or E2EE. Similarly, encryption of data at rest protects communications that are stored on a device by securing a device's operating system, apps, or files by making it unintelligible to anyone who does not have the key to unscramble it.

Americans have reaped the benefits of encryption for centuries, and it currently provides them privacy from prying eyes, while protecting information pertinent to US national security. Leaders of the American Revolution did not just use invisible ink to hide their messages; they relied on ciphers—or codes—to protect their communications.221st-century encryption uses mathematical equations to “scramble data” so that only people with the right mathematical value (i.e., key) can unscramble and understand the information.3

Unless a third party can ascertain the key, using something like a “brute force” attack to guess every possible combination of mathematical values, only holders of the key (typically the sender and recipient) can decrypt and understand the information.4This means that no one else can read the information, not even the service provider or device manufacturer. Hundreds of millions of Americans enjoy the benefits of E2EE when using private messaging or video services like WhatsApp, Signal, and FaceTime.5

What Encryption Protects

Encryption has increasingly become a mainstay of US communication infrastructure and is used to protect everything from video calls to emails to classified documents. For the public, encryption protects financial and medical data, enables online commerce, protects passwords and online browsing history, and provides privacy from criminals or other unauthorized users.6And as entire sectors of the economy and government work from home due to COVID-19, secure communications are essential. Where companies could create physical security and privacy measures in an office, such protections become ineffective or impractical to implement at home.

The current pandemic has made people more, not less, interested in securing their communications. The risks of insecure communications became readily apparent with white supremacists and others interrupting Zoom calls (i.e., Zoom bombing) hosted by Alcohol Anonymous and other organizations conducting sensitive and private meetings.7Due to overwhelming demand and growing security concerns, Zoom announced that it would provide its users the option to make their calls and chats end-to-end encrypted to ensure that unwanted parties could not listen to or disrupt sensitive conversations.8

Congress, too, favors using encryption. The Senate Sergeant at Arms approved the use of Signal, an encrypted messaging app, for staffers in 2017.9In the wake of COVID-19, the Sergeant at Arms’ cybersecurity division advised senators not to use Zoom when convening remotely because calls on the platform were not encrypted.10But it’s not just the public and Congress who rely on encryption for protection. Our national security also depends on encryption across various platforms to protect information that foreign malicious actors seek to obtain for nefarious ends. And undermining encryption could have grave implications for our national security.

What Is The Threat From Foreign Actors?

In the context of encryption, the threat from foreign actors is three-fold:

- The reliance on cyberattacks to find vulnerabilities in our systems to access national security information;

- The transport layer on which our personal and commercial information travels is vulnerable to foreign interference; and

- The supply chain of encryption devices may be controlled by foreign players.

First, foreign actors are constantly trying to gain access to sensitive US information on both encrypted and unencrypted channels. The hack of the Office of Personnel Management files by Chinese intelligence services in 201511and the earlier hack of the US military’s classified computer networks by Russian intelligence12shows a constant effort by foreign actors to gain access to US information. If companies are forced to create a backdoor for law enforcement purposes (explained in further detail below), they and law enforcement cannot prevent foreign actors from exploiting the same backdoor—now a vulnerability—to steal information.

Second, even when data is encrypted, it could travel across devices and platforms controlled by foreign actors. A message between Americans could be sent from, received on, or travel through equipment produced by companies like Huawei, which has close ties to Chinese intelligence and the People’s Liberation Army,13which is inherently vulnerable to compromise. While encrypted communications sent over such a network are protected from unauthorized interception, unencrypted communications would be readable to anyone with access to that network. Worse, providing a system of encryption that has a built-in vulnerability gives users the illusion that their communications are secure when, in actuality, they are not.

Weakened encryption represents the removal of a critical national security tool that is foundational to the operations of agencies like the Department of Defense.

Finally, even when devices are made by trusted companies, they may still be reliant on supply chains that are controlled by adversarial nations. Given the globalized production of products such as internet routers, cellphones, and servers, foreign actors have multiple entry points to compromise a system. The security of the information in this environment is all the more important. If the United States adopts policies that mandate creating a vulnerability for encryption of platforms or devices, foreign or other malicious actors can more easily take advantage of the weakness. In sum, the threat from foreign actors is multi-faceted and encryption alone cannot resolve every vulnerability or threat. But weakened encryption represents the removal of a critical national security tool that is foundational to the operations of agencies like the Department of Defense (DOD).

What Encryption Protects For National Security

DOD has increasingly incorporated encrypted devices into their operations to secure national security information. These services protect data in obvious scenarios, like the communication of classified materials. But DOD, and the women and men in our armed services, also rely on encryption to protect things like troop communications, information about troop movements, and unclassified but sensitive military research and technology shared with US contractors.

Secured buildings and online networks, such as Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities (SCIFs) and the Department of Defense Information Network (DODIN), exist to preserve the physical and electronic security of classified materials. But not all communications occur within these environments. Federal agencies deal with thousands of contractors to assist in national security missions, but who may not be using secure and encrypted systems when handling sensitive information. For example, foreign adversaries have repeatedly targeted and breached military contractors and stolen intellectual property related to the F-35 program14and hundreds of gigabytes of sensitive submarine information.15If the data was encrypted, it would have rendered the stolen materials unusable or at least required the bad actors to launch attacks “that are more difficult and costly to execute” to gain access to the key to decrypt the data.16Further emphasizing the importance of encryption to national security, DOD’s chief information officer wrote a letter in 2019 to Congress explaining that “[t]he Department believes maintaining a domestic climate for state of the art security and encryption is critical to the protection of national security.”17Translating this letter into action, components of DOD have since encouraged members of the armed forces to use encrypted messaging apps like Signal to secure their communications and ensure their safety while deployed overseas.18

Not only does DOD protect its communications (or data in motion), but DOD has also taken a number of steps to protect its stored data (or data at rest). As was raised at a recent tech CEO hearing, DOD recognizes the need to protect cloud-based information and has contracted with Google to build security and app management tools for the Department’s move to the cloud.19Similarly, DOD requires authentication and encryption for wireless access to data and encryption of information stored on mobile devices and computing platforms, which are commercially-provided.20

DOD, like everyone else, has come to rely on specifically designed encryption systems as well as commercially-provided encryption. Indeed, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) recommends that any sensitive data residing within the owner’s domain “must be protected” and specifically recommends adoption of “data encryption schemes.”21

But it is impractical and insecure for commercial vendors on which DOD relies to create secure platforms for national security agencies and not for everyone else. DOD cannot invent or assure unique access to the mathematical equations on which encryption rely. Additionally, US government experience with specially-designed legacy programs makes it harder to transition away from those programs to newer and more secure solutions, as evidenced by the CIA’s decades-long reliance on Lotus Notes for email services22or the nuclear enterprise’s use of 1970s floppy disk technology well into the 2010s.23

Ultimately, creating a vulnerability in commercial products could have serious national security effects, while also undermining the benefits the general public receives.

What Law Enforcement Wants

Attorney General Barr joins a long line of law enforcement officials who have attempted to persuade Congress to require companies to provide exceptional access to their encrypted products and services. These calls began in the Clinton administration, and have been echoed by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) officials in every administration since. Law enforcement officials point to instances or types of cases where they have had difficulty gaining access to encrypted communications that purportedly stymied their investigations.

With encryption devices readily available to anyone, criminals also use them to hide communications and acts, causing law enforcement to struggle to decrypt investigation-related information (commonly referred to as the “going dark” challenge). In response, law enforcement agencies have argued that encryption is a significant threat that enables malicious actors to commit their crimes or acts, and that law enforcement is unable to access information to effectively stop or prosecute them.24In a recent example, DOJ claimed an iPhone’s encryption hindered its investigation into the 2019 shooting at the naval air station in Pensacola when they were trying to assess the shooter’s motives. Five months after the incident, DOJ and the FBI were able to circumvent the encryption on the phone through an undisclosed method and found that there was coordination between the shooter and an Al-Qaeda affiliate.25

DOJ and other agencies have used Pensacola and other cases as evidence for why they need “extraordinary access” or “backdoor access” to encrypted information, claiming that encryption is undermining national security. This argument is nearly 30 years old. Backdoor proponents argued for the deployment of the infamous “Clipper Chip” in 1993 to provide law enforcement with a backdoor to encrypted messages.26Today, DOJ and FBI vilify companies that offer encryption services. In 2015, when the FBI could not readily access information on the iPhones of the San Bernardino terrorists, the government pursued legal actions against Apple claiming that the company was not complying with orders to decrypt data on the phones.27The FBI Inspector General would later release a report concluding that the FBI’s litigation was unwarranted and improper.28In 2018, FBI Director Chris Wray claimed that investigators were locked out of nearly 7,800 devices they had legally obtained because of encryption protections.29Internal metrics, however, revealed that the number was closer to 1,000 to 2,000 devices, raising questions that FBI leadership was intentionally overinflating the problem posed by encryption.30Despite overstating the scope of the issue, DOJ echoed this claim again in early 2020 when Attorney General Barr criticized Apple for refusing to assist in cracking the Pensacola shooter’s phone to obtain relevant information for the investigation (Apple claims to have legally complied with all requests).31He would go on to say, “Our national security cannot remain in the hands of big corporations who put dollars over lawful access and public safety,” and called for a “legislative solution.”32

DOJ undermines its stated justifications for a legislative fix to solve its encryption challenges by the actions it has taken and the laws at its disposal to hold private companies accountable. In both Pensacola and San Bernardino, the FBI used techniques to crack the encryption without the assistance of Apple or a built-in backdoor.33Similarly, DOJ Inspector General investigations have suggested that while senior leadership may not be aware of existing capabilities to unlock encrypted phones, the officials in charge of this technology have far greater ability to circumvent encryption than the FBI or DOJ leadership publicly disclose.34Lastly, DOJ and others point to pedophiles using encryption services to exchange and view child sexual abuse material (CSAM) as a core reason why there needs to be built-in backdoors. What they fail to mention, however, is that current law requires online companies to report this type of material and can be held liable if they fail to do so.35Specifically, federal law (18 U.S.C. §§ 2251-2260A) requires that providers must report CSAM when they discover it and preserve it or risk substantial penalties if they fail to comply.36Notably, 45 million CSAM photos and videos were submitted in 2018, but DOJ struggles to manage the growing caseload.37

DOJ has made broad claims about the importance of backdoors, but these claims contain serious and lingering questions about whether backdoors are truly necessary. To highlight this reality, former FBI General Counsel Jim Baker noted: “Perhaps most importantly, what many people on all sides of the debate will admit in private is that the United States has not experienced a terrorist or other attack of sufficient magnitude where encryption clearly played a key role in preventing law enforcement from thwarting it so as to change the contours of the public debate and motivate Congress to act.”38

How Mandatory Exceptional Access Is A Vulnerability

If backdoors were introduced into encrypted systems, malicious actors will exploit those system’s vulnerabilities; steal the keys held by law enforcement, national security agencies, or companies; and move their communications to non-US platforms that are outside the reach of US law enforcement, while undermining US global influence. Attorney General Barr and other advocates of built-in backdoors either ignore or dismiss the fact that weakened encryption, at best, jeopardizes Americans’ privacy and, at worst, imperils national security.

Attorney General Barr and other advocates of built-in backdoors either ignore or dismiss the fact that weakened encryption, at best, jeopardizes Americans’ privacy and, at worst, imperils national security.

However, in response to Barr’s call for legislation, a number of legislators recently introduced a pair of bills to weaken encryption standards for law enforcement purposes. First, a bipartisan group of senators introduced the “EARN IT Act” (S. 3398) to remove criminal and civil liability protections for technology companies at the state level if they do not remove online CSAM, even if they are unable to identify the illegal content because it was encrypted. While the bill was amended in an attempt to protect encryption, the expansive legal exposure that still exists in the bill could force providers to weaken their encryption standards or stop offering encryption altogether.39Senate Republicans have also released a second bill that directly targets encryption. The “Lawful Access to Encrypted Data Act” (S. 4051) would require large companies to build backdoors by default. It would require any company that receives an order from a court or a directive from DOJ compelling them to provide technical assistance in executing a warrant to build a backdoor to access encrypted data or communications.40But by creating the extraordinary access that DOJ seeks, these laws would, in effect, destroy US encryption by (1) weakening its overall security; (2) providing opportunities for malicious actors to access encrypted information; (3) discouraging domestic investment in and development of encryption platforms; and (4) weakening US negotiating positions internationally (discussed in the Reciprocity & Global Implications section below).

Simply put, if these bills become law, the built-in backdoors would make an encrypted system insecure. Instead of limiting the communication strictly to the sender, recipient, or holder of the data, a third party could have access to any and every communication. While this might seem similar to a wiretap, encryption backdoors are fundamentally different. In fact, the modern law establishing wiretaps, the “Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act of 1994” (P.L. 103-414), contains an “encryption carve out” for telecommunication carriers, therefore implicitly legalizing encryption while allowing for wiretaps to occur (CALEA notably excludes internet service providers from wiretapping).41Encryption experts also unanimously agree that DOJ or a private company cannot ensure it is the only party with that extraordinary access.42Once a backdoor is created, it becomes a matter of time for nefarious actors to discover and exploit it. In other words, our adversaries can exploit the now built-in vulnerability or target the private companies and law enforcement and national security agencies that hold the key.

These fears are not mere speculation as malicious actors have compromised private and government institutions with weak encryption and security standards. For example, Juniper Networks announced that it had backdoors unintentionally inserted into some of its products that it distributed to multinational corporations and other businesses over a seven-year period.43The National Security Agency (NSA) developed the algorithm used for Juniper Networks’ encryption, which outside encryption experts believed had a backdoor.44Though the extent of any criminal or foreign exploitation of this backdoor is still under investigation, the ongoing risk posed by a backdoor to user security is ever-present.45Similarly, DOD banned the use of fitness tracking devices for deployed troops after a private company publicly released geolocation data that compromised troop movements in “unknown and potentially sensitive sites” overseas.46While this information was not encrypted, it shows the risk to national security personnel using unencrypted commercial applications and communications systems.

If backdoors did exist with tech companies or federal law enforcement agencies holding the keys to access the data, we know that the federal government would struggle to protect the system from malicious actors. In 2017, the CIA experienced the “biggest unauthorized disclosure of classified information” in the agency’s history due to “woefully lax” security measures (this incident is known as “Vault7”). As a result, the CIA shuttered intelligence operations that exploited vulnerabilities in systems.47Similarly, the Shadow Brokers, a criminal enterprise, compromised the NSA and released stolen vulnerabilities that existed in Microsoft’s software. Malicious actors would later weaponize those vulnerabilities by creating the WannaCry and NotPetya ransomware,48which caused billions of dollars of damages worldwide.49

Even if companies could build secure backdoors—which by definition is impossible—and the US government employs the best cybersecurity mechanism to secure the keys to access the backdoor, non-state criminal actors and terrorists could use an encryption platform based outside of US jurisdiction. Millions of people use the encrypted messaging app Telegram instead of Apple’s messenger or Facebook’s WhatsApp specifically because they are not American.50Malicious actors are not exempt from this practice. ISIS, for example, has over 600 channels on Telegram and uses its encrypted messaging system for security purposes, despite relying on public channels that could undermine their security.51And when the Snowden leaks revealed that intelligence agencies were spying on Americans’ communications, Al-Qaeda changed the encryption products they used and reportedly created their own encrypted messaging system.52Those who commit cybercrime or other malicious actors that rely on encryption will not stay on platforms they know to have vulnerabilities, like in a system with mandated extraordinary access for law enforcement.

Proponents of backdoors believe that, if we give law enforcement a key, they will be able to keep it safe. The problem is that law enforcement at all levels would want a key, or indeed a collection of keys for each encryption platform subject to a backdoor requirement, from US national security agencies down to county sheriffs. The examples above reveal that, if the top echelons of national security like the CIA or NSA are unable to keep backdoors secure, it is highly unlikely that a local sheriff’s department will be able to keep them safe. Experts have also found that as society has embraced encryption platforms the “damage that could be caused by law enforcement exceptional access requirements would be even greater today than it would have been 20 years ago,” and that any “globally deployed exceptional access systems raises difficult problems about how such an environment would be governed” as a practical matter.53

If exceptional access were available to the full range of law enforcement agencies—federal, state, local, tribal—it would be nearly impossible to keep the system secure from malicious actors or foreign adversaries.

Reciprocity and Global Implications

In addition to the security risks that come from creating a system that allows backdoor access, mandating such a system would also adversely impact global privacy and competitiveness, degrade global norms, and create dangerous precedents for foreign adversaries—like China and Russia—to pursue similar options. As of 2016, over 800 encryption products exist in the global marketplace, with only 300 produced in the United States. If the United States mandated lawful access, then users will undoubtedly flock to products produced in countries that do not have similar mandates, thereby weakening US companies’ competitiveness in the global economy.54Michael Hayden, the former director for the NSA and CIA, also noted that China and Russia would exploit US communication platforms knowing that there are backdoors built into them.55

Other countries may also follow suit and create their own “lawful access” mandates, leading to “a patchwork of multinational regulatory structure” and more restrictions on data transfers, which could undermine international law enforcement efforts.56The United Kingdom, for example, passed and introduced legislation that could force companies to create backdoors for law enforcement purposes.57Australia, too, passed a law in 2018 that requires platforms to provide access to encrypted communications.58And India finalized a proposal in early 2020 to require companies with more than five million users to make “traceable” any post performed on their platform, which would essentially destroy encryption.59This is a worrisome trend that would be exacerbated by a US law. Under the guise of backdoors becoming an international standard, our adversaries will no doubt create or strengthen mandates to access encrypted communications to clamp down on their citizens and commit human rights atrocities. Having imposed mandates to require access, the United States’ pleas for other countries to respect the privacy of communications within their borders would fall on deaf ears, imperiling the communications of Americans overseas, journalists, human rights and democracy advocates, and others.

Alternative Approaches

When considering solutions to address crime perpetrated online, Congress should consider legislative solutions that address specific challenges for particular crimes rather than undermining the security of encryption systems that play a critical role in safeguarding our national security. In addition, Congress should use its oversight power to ensure law enforcement is collaborating with the private sector and using their resources and authorities effectively and efficiently to conduct investigations.

Some Members of Congress have already begun to explore alternative legislative solutions that do not rely on granting extraordinary access. For example, in response to the EARN IT Act, which aims to reduce CSAMs at the expense of encryption, Democratic senators introduced the “Invest in Child Safety Act” (S. 3629). This Act would significantly increase the number of personnel who work on these cases, expand funding for various agencies such as the Internet Crimes Against Children Task Forces, and create a new White House office to coordinate federal efforts.60The senators rightfully criticize DOJ’s view that weakened encryption would be a panacea to CSAM and point out that DOJ has “actually cut more than $60 million from programs to prevent child exploitation and support victims.”61Similarly, the “Technology in Criminal Justice Act” (H.R. 5227) would also assist law enforcement’s efforts by increasing funding and improving training for law enforcement at the federal, state, and local levels in identifying, collecting, and using digital evidence that is legally available to them.62When evaluating these pieces of legislation or creating new proposals, Congress should consider the framework created by the National Academies of Science and the guidelines developed by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Encryption Working Group; organizations that sought to develop methodologies to assess legislation regarding encryption.63

While these legislative proposals do not fully resolve law enforcement’s problems, they touch on three important issues. To overcome the challenges associated with encryption, Congress should push federal law enforcement to work with private partners, bolster its cyber investigative capacities, and act on existing laws to pursue malicious actors, while preserving Americans’ privacy and US national security interests.

First, Congress should begin by understanding the actual challenges that impede public-private partnerships in conducting investigations to create nuanced legislation rather than eliminating encryption whole cloth. Despite Attorney General Barr’s assertions, private companies have been willing partners in criminal and national security matters. Apple has repeatedly provided significant amounts of information outside of encrypted communications to assist investigators, such as in the San Bernardino and Pensacola cases.64Congress should have law enforcement build upon these relationships by considering proposals that improve these relationships, such as recommendations identified by the Center for Strategic International Studies’ (CSIS) report “Low-Hanging Fruit: Evidence-Based Solutions to the Digital Evidence Challenge,” whose recommendations were largely incorporated in the “Technology in Criminal Justice Act” (mentioned above).65Among their proposals, CSIS recommends that law enforcement can benefit from more robust training on what data is legally available, the companies that can provide that information, and how to request it. The report also provides detailed recommendations on how companies can enhance their interactions with law enforcement, too.66

Second, Congress needs to look at existing law enforcement capabilities and authorities to determine if any potential benefits of extraordinary access can be satisfied through other investigative means. Law enforcement leaders like Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance have noted that they do not need a backdoor mechanism to resolve investigations complicated by encryption, but that companies should “comply with warrants issued by impartial judges upon findings of probable cause.”67As both the Pensacola and San Bernardino examples showed, law enforcement had the authority to obtain encrypted devices through a warrant, and with those devices in hand, circumvented the encryption on the individual devices to obtain the encrypted information. Private companies could also be encouraged to develop platform safety policies that enable their users to report abusive or illegal activity and share the relevant encrypted communications with the provider. Facebook, for example, allows users to “voluntarily provide [the company] with encrypted content,” which allows them to “review and determine whether it is violating and then impose penalties and/or report the matter to law enforcement, if necessary.”68

Lastly, Congress should hold federal law enforcement accountable by asking how current legal structures restrict their ability to perform criminal investigations and identify areas for improvement. As mentioned, DOJ already retains the authority to prosecute tech companies if they violate CSAM laws. DOJ has also “neglected even to write mandatory monitoring reports, nor did it appoint a senior executive-level official to lead a crackdown” on CSAM or “set goals to eliminate them.”69Therefore, DOJ has existing legal authorities prosecutors could pursue and enforce to convict bad actors while preserving encryption. Further, these tangible policy solutions will greatly improve law enforcement’s ability to close the cyber enforcement gap where only 3 in every 1,000 cybercrimes see an arrest.70

Reliance on extraordinary access opens national security agencies and officials to access and exploitation by malicious foreign and non-state actors. Ultimately it is the joint pursuit of alternative solutions that will both grant law enforcement the necessary resources and authority to combat cybercrime while protecting and relying on standard Fourth Amendment privacy protections. The Fourth Amendment guarantees individual adjudication for things like a warrant, not the broad scope of access to all communications that exceptional access would grant.71These courses of action would be consistent with that constitutional protection, consistent with efforts that have demonstrated success, and consistent with protecting critical national security principles and priorities.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, criminals and terrorists abuse encryption platforms to stymie law enforcement efforts. Yet, these same tools are critical and fundamental parts of protecting classified materials from unauthorized disclosure. DOJ claims that allowing for exceptional access to these protected systems would not undermine their security, implicitly arguing that such access will not degrade overall national security and personal and commercial privacy. These arguments, however, fail to take account of existing lessons learned about the dangers of such access and overstate the importance of backdoors while distracting from more basic investment and attention to building capabilities to combat crime. Encryption backdoors cannot be the shortcut we pursue to tackle internet-enabled crime as the risk to national security is far too great and the upside decidedly questionable. Instead, Congress should ensure that federal agencies bolster public-private partnerships, receive the resources to pursue criminals, and hold the Executive Branch accountable to implementing existing laws, rather than seeking out a shortcut that is inconsistent with national security and civil liberty principles.