Report Published July 22, 2024 · 10 minute read

What’s Behind Drug Shortages and What to do About It

David Kendall & Darbin Wofford

Takeaways

Shortages of generic drugs in the United States are persistent and growing. The underlying problem is that the pursuit of low prices has come at the expense of a reliable supply. Congress can change market dynamics and federal policies to prevent shortages with these actions:

- Incentivize responsible private purchasing for drugs vulnerable to shortages.

- Exempt drugs with shortages from inflation rebates in Medicaid.

- Limit the use of a federal drug discount program for drugs vulnerable to shortages.

A high school football coach with stage IV cancer in Milwaukee, Wisconsin recently died because of a shortage of drugs. Following surgery to remove most of his tumor, Jeff Bolle had four rounds of chemotherapy, two rounds short of what he needed because of shortages.1 The final treatments could have given him another year with his family and team.

The United States has a shortage of over 100 drugs—mostly generic drugs and concentrated in injected drugs. And the shortage is getting worse.2 Despite high health care spending overall, the problem behind the shortages is that the pursuit of low prices has come at the expense of a reliable supply. Our highly competitive market for generic drugs has run amok with aggressive buying practices and government policies that did not anticipate such low prices. In this report, we explain the economic problems behind the generic drug shortages and propose remedies that are consistent with the bipartisan draft legislation from Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-ID).3

How Bad is the Drug Shortage Problem?

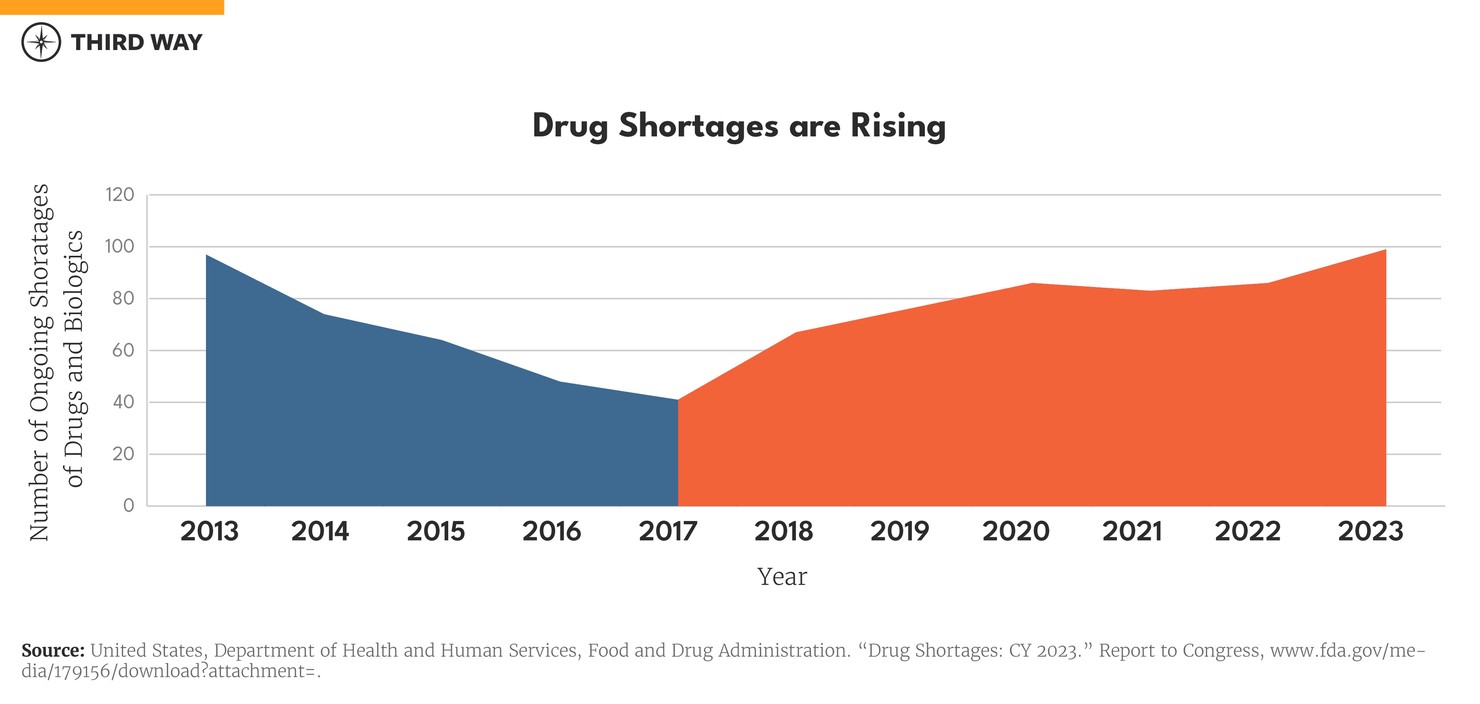

It’s getting worse, and patients are dealing with a growing shortage of drugs. After decreasing for much of the last decade, the number of drug shortages has been rising, as shown in the chart below. From 2017 to 2023, the number of drugs and biologics with ongoing shortages has more than doubled from 41 to 99, according to the Food and Drug Administration.4 Other data sources confirm this trend has continued into 2024.5 While the pandemic created shortages of drugs in specific areas like sedation for patients on ventilators, the shortage problem has not gone away as supply chains have recovered.6

The number of drugs with shortages may seem small since more than 32,000 generic drugs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).7 The typical shortage, however, affects half a million patients with cost and access problems, according to estimates from the Department of Health and Human Services.8 The effects can be severe for vulnerable patients:

- Cancer drugs for children are 90% more likely to have a shortage.9

- Children with cancer are more likely to suffer relapses and have worse side effects from treatment because of shortages.10

- People with Medicaid coverage are nearly twice as likely to be affected by shortages.11

Drugs with shortages range from chemotherapy to antibiotics. The most common shortages are for drugs used to treat the nervous system like attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder drugs.12 Those shortages have left children unable to succeed at school and cope with a host of social challenges.13

Under an executive order by President Barack Obama in 2011, many shortages have been prevented.14 For example, the FDA temporarily allowed manufacturers to include filters with an injectable drug that let doctors eliminate a contaminant rather than end distribution of life-saving drugs.15 In 2023, the Food and Drug Administration prevented 236 drug shortages by working with manufacturers that have reported problems earlier and used its regulatory flexibility to keep critical drugs available without compromising the drugs’ safety and effectiveness.16 More FDA approvals of generics manufacturing applications following the backlog in the 2000s and early 2010s have also helped prevent shortages.17

But shortages are an ongoing problem despite the progress. As Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) recently stated: “It is unacceptable that America is consistently running out of affordable and essential generic medicines.”

“It is unacceptable that America is consistently running out of affordable and essential generic medicines.”—Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR)

What’s Causing the Shortage?

The United States has some of the lowest prices in the world for generic medicine. Our prices are one-third less than many other countries.18 Moreover, nine of every ten drugs we use are generic medicines.19 With such a large volume of drugs at stake, the drive for lower prices is critical for the patients’ and taxpayers’ wallets. The problem, however, is that the pursuit of low prices has come at the expense of a reliable supply and preventable shortages.

Market problems

Generic prices have been falling. From 2017 to 2022, the average price for generics fell 3.2%.20 Average patient costs for generic drugs have also decreased, from $7.19 to $7.12. When prices are low, shortages are more common. Over half of drugs with shortages have a price of less than $1.00 per unit or dose.21

Big purchasers, like group purchasing organizations that combine the purchasing power of hospitals and pharmacies, often have contracts with manufacturers for a fixed price for an extended period, but these contracts can be cancelled if the purchaser gets a lower price elsewhere.22 That means the manufacturer has little incentive to build up a reliable supply and, instead, just focuses on delivering immediate orders. Three organizations purchase about 90% of generic drugs in the United States, which gives manufacturers few options to set stable supply terms.23

As a report from the Department of Health and Human Services states:

Generic drug manufacturers face intense price competition, uncertain revenue streams, and high investment requirements to maintain mature manufacturing quality systems. These conditions can incentivize reductions in manufacturing costs to potentially unsustainable levels, drive existing manufacturers out of the market, and deter potential market entrants—even when a drug is actively in shortage.24

With a brittle supply chain, the shuttering of manufacturing facilities for safety or other reasons becomes catastrophic.25 What little excess supply exists quickly gets bought up by the biggest purchasers, leaving shortages for others.26 Other supply chain disruptions (like the lack of raw ingredients) can often be anticipated, but a manufacturer may not have a strong incentive to plan ahead, given low profits margins for their drugs.27

Another factor that can make a generic market brittle is that each generic drug tends to be dominated by a small number of manufacturers. More than half of generic drugs have only two manufacturers, while less than 40% of generic drugs have four or more manufacturers.28 At the same time, no generic manufacturer dominates the market overall. Globally, the top 10 manufacturers capture only 10% of the total revenue.29 It is a market where lots of smaller manufacturers get a toehold for a specific generic drug, often for a short period of time, which then leads to underinvestment in manufacturing capacity.30 The bottom line is that the drive to lower prices without full attention to a stable supply is keeping the supply chain too brittle for patients.

Federal policy problems

Federal policy over the pricing of drugs also contributes to the shortage problem. Under federal law, price increases for drugs in Medicaid programs, which are run by the states, cannot exceed inflation rates or they must pay Medicaid a rebate. That means when a drug is in short supply, manufactures cannot receive increased payments through Medicaid to offset unusual costs of correcting the cause of a shortage. The Medicaid inflation rebate is determined by average price, meaning fluctuations in purchasing can cause a generic manufacturer to pay a rebate even if it didn’t increase its own price. This problem is especially acute for drugs that are disproportionately covered by Medicaid like cancer treatment drugs for children.

Similarly, the 340B Drug Pricing Program has driven the price of generics down to as little as a penny, which further undermines the ability of generic drug manufactures to remain in low-margin markets and respond to shortages. As a requirement for their drugs being covered under Medicare and Medicaid, generic drug manufacturers must participate in the 340B program to give hospitals and safety net providers (like community health centers) discounts for purchased drugs. Most hospitals that qualify for the program serve a larger portion of Medicare and Medicaid patients or are hospitals located in rural areas.

The 340B program plays a role in underpricing drugs, leading to drug shortages or worsening those that exist.31 For generic drugs, these discounts are significant for those that are already purchased at low prices. In many cases, generic drugs can be purchased by a 340B provider by only one cent, discouraging production of these drugs.

What Can End Shortages?

Fortunately, many organizations have been pursuing solutions. One key example is Civica, a nonprofit purchasing organization formed by hospitals and foundations to address shortages. It has been successfully delivering a reliable supply of drugs to its member organizations, even amid shortages.32 It examined the supply chain for weaknesses in everything from the sourcing of manufacturing ingredients to inventory controls for scarce and vulnerable generic drugs with the cooperation of a diverse group of stakeholders.33 As a result, it has changed the way its member hospitals and other buyers within its membership purchase drugs at sustainable prices.

Congress can build on that kind of leadership by improving purchasing practices and leveraging policy changes to create stable supplies. Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-ID) recently unveiled a draft bill, the Drug Shortage Prevention and Mitigation Act, to do just that.34 It authorizes three new tools to prevent shortages for vulnerable drugs, which the administration would identify:

First, incentivize hospitals and group purchasing organizations to purchase drugs responsibly. The Senate Finance Committee draft creates the Medicare Drug Shortage Prevention and Mitigation Program. It allows for group purchasers, wholesalers, and health care providers (who opt into the program) to receive financial incentives for responsible purchasing practices in their contracts with generic manufacturers for drugs that are vulnerable to shortages.35 These purchasing practices include long-term contracting, purchasing volume commitments, and stable pricing, which are consistent with best practices outlined in a recent white paper from the Biden Administration.36 To incentivize this responsible purchasing, program participants would receive bonuses through quarterly payments, along with additional bonuses for performing well in outcome measures like longer-term contracting, volume commitments, stable pricing, and maintaining a buffer supply of drugs. Under this program, generic manufacturers would have the certainty to continue production of needed medicines.

Second, exempt drugs in shortage from Medicaid inflation rebates. Medicaid’s mandatory inflation rebate underprices generic drugs, contributing to shortages. The Senate Finance Committee draft would suspend Medicaid inflation rebates for all generic drugs that do not have competition from other generic manufacturers as well as any generic that costs less than $100 annually. This is consistent with the inflation rebates for drugs in Medicare included in the Inflation Reduction Act. It also allows the Secretary of Health and Human Services to adjust or exempt rebates for drugs in shortage, risk shortage from severe supply chain disruptions, or are vulnerable to be in shortage.

Third, limit the 340B Drug Pricing Program’s impact on drug shortages. Like the Medicaid inflation rebate, 340B discounts result in the underpricing of generic drugs, contributing to shortages. The Senate Finance Committee draft includes a partial solution to the 340B problem. It uses the voluntary Medicare Drug Shortage Prevention and Mitigation Program mentioned above to require program enrollees to stop using 340B discounts (and other discounts) for generics vulnerable to shortages. While very helpful, its impact would be limited to generic drugs purchased by those organizations enrolled in the program. To limit 340B’s very low prices for all generics vulnerable to shortages, Congress should allow the Secretary of Health and Human Services to temporarily halt 340B discounts for all drugs with a current or potential shortage.

Conclusion

Generic drugs are an American success story, but patients deserve a reliable supply of the critical and life-saving medicine they provide. With over 300 drugs experiencing shortages, Congress must act swiftly to prevent patients from further suffering, and even death. The Senate Finance Committee draft legislation takes tremendous steps to remedy the economic drivers of drug shortages.