Report Published November 14, 2019 · 10 minute read

Why Do Only a Tiny Fraction of Jobseekers Participate in Registered Apprenticeships?

Kelsey Berkowitz

Takeaways

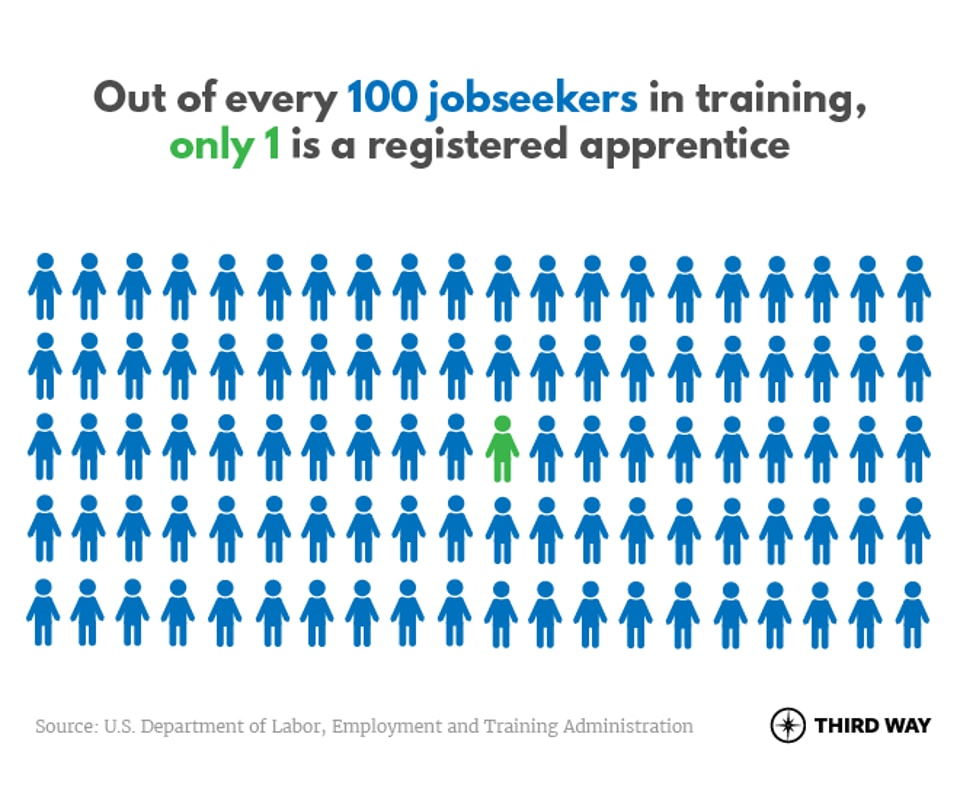

Of the jobseekers who visit an American Job Center and enroll in job training, less than 1% enroll in registered apprenticeships. And if that wasn’t bad enough, there are further disparities by race, gender, and background characteristics.

Simply put, registered apprenticeships are an afterthought in our nation’s job training system. This hinders access to economic opportunity, because apprenticeships are a proven model for helping people earn money while learning skills for in-demand jobs.

This report looks at why less than 1% of jobseekers participate in apprenticeships, why it’s a problem, and what we can do about it.

Of the 30 fastest growing occupations reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 24 require more than a high school diploma.1 It’s clear that in the 21st century economy, access to opportunity has become far more dependent on a person’s skills and credentials. Because of this, we have to ensure all Americans can access training opportunities that are effective and lead to good-paying careers.

That’s why Congress passed the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), which sets national job training policy, authorizes funding for the public job training system, and specifies performance data to be collected. Under WIOA, state and local workforce boards play an integral role in our nation’s job training system, from creating strategic plans to developing training policies and convening stakeholders. The boards also operate American Job Centers, formerly known as One-Stop Career Centers. American Job Centers provide a single physical location where jobseekers can go to access a range of job search services, including career counseling and access to job training programs.

But recent data shows a serious gap in WIOA training programs. While interest in expanding apprenticeships has heightened in recent years, registered apprenticeships (RAs) play only a small role in our public job training system. Registered apprenticeships are a proven model for helping people get skills for in-demand jobs, and apprentices earn money while training. Yet just a tiny fraction of the jobseekers who visit American Job Centers enroll in registered apprenticeships. This report looks at why this is and what we can do about it.

What the Workforce Data Show

The most recent WIOA data show that, of the people who visit an American Job Center and enroll in job training, less than 1% enroll in registered apprenticeships. Specifically, out of 132,616 people enrolled in job training under WIOA in 2017, just 1,099—or 0.8%—were enrolled in registered apprenticeships.2 This share has increased since 2013, when just 362 out of 191,651 trainees (0.2%) were in registered apprenticeships. But it is still a tiny fraction of trainees.3

By contrast, about 60% of trainees enroll in “Other Occupational Skills Training,” which includes other training programs that teach people skills needed to do specific jobs. These programs may not have the same structure that defines apprenticeships—namely on-the-job training combined with classroom training—and aren’t registered as apprenticeship programs.

And while apprenticeship participation among WIOA trainees is low across the board, there are further disparities by race, gender, and background characteristics. Among adult trainees:

- Apprenticeship participation is rarer among African Americans. Among African American trainees, 0.4% participated in RAs, compared to 1.2% of white trainees and 1.3% of Latino trainees.

- Apprenticeship participation is higher for males than females. 1.7% of male trainees participate in RAs, compared to 0.2% of female trainees.

- Apprenticeship participation is low among long-term unemployed trainees. Participation is just 0.5% among trainees who have been out of work for at least 27 weeks.

- Participation is higher for veterans than trainees overall. 2.1% of veteran trainees participate in RAs, compared to 0.9% of adult trainees overall.4

It’s important to remember that many people who enroll in apprenticeship programs never set foot in an American Job Center, and many good apprenticeship programs are not registered. However, the WIOA data we analyze in this paper focuses on registered apprenticeships and jobseekers who visit American Job Centers. This data indicates a severe lack of integration between our registered apprenticeship system and our public workforce development system.5

Why Is This a Problem?

This lack of integration between apprenticeships and the public job training system hinders access to economic opportunity. Registered apprenticeships are a proven model for helping people get skills for in-demand jobs, and apprentices earn money while training. The average wage for a fully-proficient worker who completes an apprenticeship is $50,000 annually. Apprentices who complete their programs earn approximately $300,000 more during their careers than non-apprenticeship workers.6 And 91% of apprentices who complete an apprenticeship are still employed nine months later.7

These outcomes make sense given that registered apprenticeships are inextricably tied to employer demand—something our nation’s job training system as a whole should strive toward. Apprenticeships aren’t a fit for all jobseekers, and there are other effective training models out there, but apprenticeships should be a robust part of our training system. The fact that less than 1% of jobseekers train this way suggests we’re not there yet and we have a lot of room to grow.

Given their positive outcomes, WIOA envisioned greater integration of registered apprenticeships into our workforce development system. The law, passed in 2014, took several steps to promote that integration:

- Making registered apprenticeships automatically eligible for placement on each state’s list of eligible training providers. This makes apprenticeship programs eligible for trainee enrollment and for WIOA funding.

- Allowing WIOA funding to support registered apprenticeships. Specifically, WIOA funds can be used to pay for classroom training, on-the-job-training, and supportive services that allow people to participate in apprenticeships.

- Requiring state and local workforce development boards to include representatives from the registered apprenticeship system.

- Making the Registered Apprenticeship Certificate of Completion a recognized postsecondary credential under WIOA. This puts apprenticeship programs on an equal footing with other training programs that provide different types of credentials.8

Yet, WIOA data shows that we’re still a long way from achieving the integration WIOA envisioned, five years after it was signed into law. While apprenticeships are not the only way to train people, they have many upsides and there is a ton of room to expand the reach of apprenticeships in our public job training system.

Why Is This Number So Low?

There are both demand and supply reasons for why apprenticeships aren’t a robust part of our job training system. On the demand side, many jobseekers feel that apprenticeships take too long and prefer shorter-term training models that will return them to work more quickly. They may also feel that the starting pay for apprenticeships is too low.9 This suggests a need for better marketing about the benefits of apprenticeships so people know they will earn money from Day 1 of their apprenticeship, and will see their wages increase over the course of their apprenticeship. While some apprenticeship programs are six years long, many occupations have apprenticeship programs that last just one or two years.10

On the supply side, many employers lack knowledge about apprenticeships and their potential benefits, or don’t want to go through the burdensome process of registering an apprenticeship program. This translates into fewer apprenticeship slots for potential trainees, and this lack of availability may help explain why so few jobseekers participate in them.

While ensuring high-quality apprenticeships is key, many employers feel that requirements for registered apprenticeship programs are too inflexible to meet their needs. For example, registered apprenticeship programs must meet time requirements that employers feel are outdated—144 hours of classroom training and at least 2,000 hours of on-the-job training. Many employers would prefer apprenticeship programs that are more competency-based, allowing apprentices to progress through their training as they master skills. However, the US Department of Labor and State Apprenticeship Agencies don’t always approve competency-based programs.

Employers often have to register programs across multiple states, and registration requirements and approval times can differ across states. After an apprenticeship program has been approved, employers must commit administrative staff time to meeting burdensome data reporting requirements across multiple data systems and formats.11 Because of the obstacles employers face, many choose not to register their apprenticeship programs, or choose not to create them at all.

Also on the supply side, state and local workforce boards may lack the resources, experience, and knowledge needed to engage with employers, market apprenticeships to employers and jobseekers, or otherwise integrate apprenticeships into their work. In 2017, the National Association of Workforce Boards (NAWB) and Jobs for the Future surveyed workforce boards and found that many boards don’t feel like they have enough knowledge about how apprenticeships work, and as a result feel ill-equipped to promote them to employers and jobseekers.12

What Should We Do to Expand Registered Apprenticeships?

To expand the reach of registered apprenticeships in our job training system, policymakers should take the following steps:

- Establish dedicated apprenticeship coordinators in each state. For example, Third Way’s Apprenticeship America proposal would reach 1 million apprenticeships each year by establishing an Apprenticeship Institute in each state. These Institutes would function as hubs by recruiting employers to launch new apprenticeship programs, helping employers register and develop apprenticeship programs, and recruiting people to participate in apprenticeships. Workforce boards are currently tasked with performing many of these functions, but they have a number of other responsibilities under WIOA. If we’re serious about making apprenticeships a robust part of our training system, we should create entities in each state that work exclusively on expanding apprenticeships.

- Reform the apprenticeship registration process to make it easier for employers to create new programs. For example, policymakers should make it easier for employers to register apprenticeship programs that are more competency-based, and should streamline data reporting requirements. New programs should fit employer needs while maintaining quality.

- Boost funding for job training programs. WIOA has been underfunded for years, meaning fewer dollars are available to provide services and help people afford training programs. Adjusted for inflation, WIOA funding to the states has fallen by 40% since 2001, from $4.7 billion in 2001 to $2.8 billion in 2019.13 In 2017, the United States spent just 0.03% of its GDP on job training, compared to an OECD average of .12%, four times higher.14 To be sure, employers should have skin in the game in developing a skilled workforce, but we’ll still need an infusion of public funding to fill in the gaps.

- Provide more assistance to workforce boards and American Job Center staff on apprenticeships. NAWB’s 2017 survey offers rich insight into where workforce boards need help and should be used as a starting point. For example, workforce boards need marketing materials, such as informational brochures, to use when talking to employers and jobseekers about apprenticeships. The US Department of Labor or Government Accountability Office should also find out which workforce boards are doing a good job integrating apprenticeships into their workforce systems and create a report of best practices that can be distributed to all workforce boards across the country.

Conclusion

Registered apprenticeships should be a robust part of our job training system, because they’re a proven workforce training model that allows people to earn money while learning in-demand skills. Yet of the people who walk into an American Job Center and enroll in job training, less than 1% enroll in registered apprenticeships. We need to do more to integrate apprenticeships into our job training system. We should create apprenticeship hubs that will market apprenticeships to employers and jobseekers, make it easier for employers to create apprenticeship programs, and help the people who run our nation’s job training system integrate registered apprenticeships into their work. By expanding the reach of registered apprenticeships, we can ensure more Americans have access to these training opportunities and the skills needed to thrive in this economy.