Report Published April 23, 2019 · 18 minute read

Wisconsin

Lindsey Walter

More from this series Move over, Silicon Valley. The Midwest is poised to drive clean energy innovation.

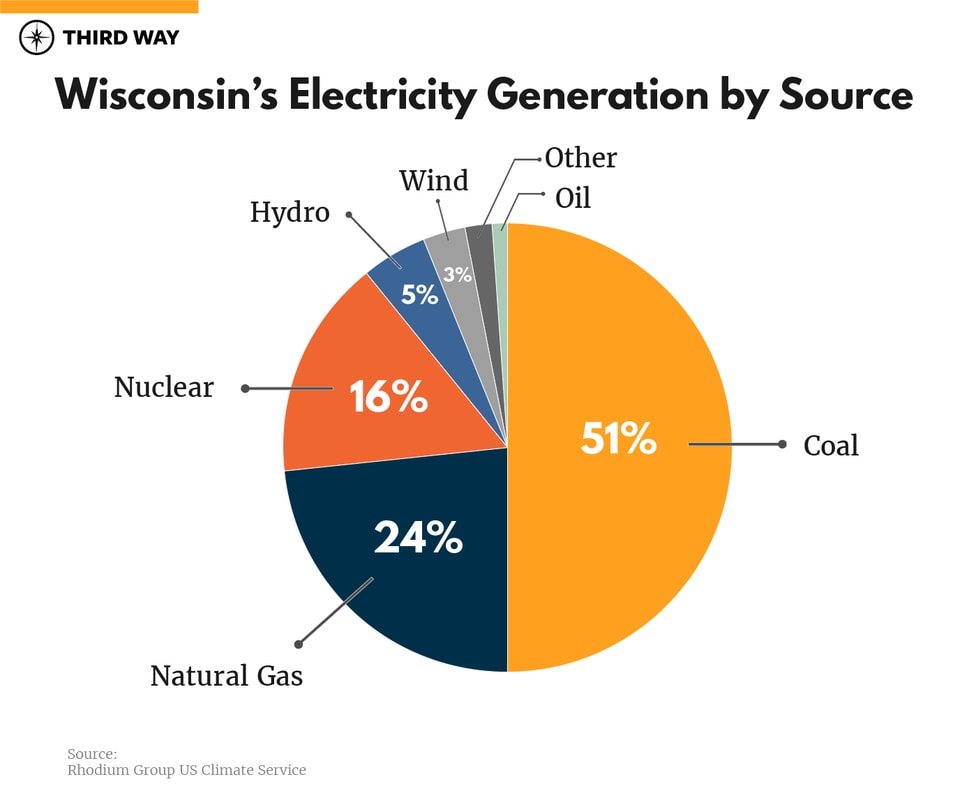

View seriesWisconsin relies heavily on coal to produce electricity and has fallen behind neighboring states in the growth of renewables. However, this is far from the full story. After talking to many business leaders, innovators, and other experts working in Wisconsin’s clean energy industry, it is clear that the state is entering a new era of expanded clean energy innovation and deployment. For starters, Wisconsin researchers developed an award winning 18 MW solar installation,1 and solar installations are predicted to grow by 20 times current levels within the next few years.2 Additionally, researchers are conducting extensive research on next-generation nuclear power plants.3 Wisconsin has also progressed with hydroelectric power, acquiring electricity from 150 dams and expanding to more,4 and wind power, with wind farms capturing energy from the strong winds coming off Lake Michigan and innovators looking to improve their efficiency. As clean energy becomes a larger part of the state’s electricity supply and economy, innovation will play a critical role in positioning Wisconsin as a leader in the field.

The average share of electricity generation by source in Wisconsin in 2018. Coal is still overwhelmingly the largest source, but the share of clean energy, including wind, solar, and hydro, is slowly growing.

It may come as a surprise that Wisconsin actually has a long history with clean energy innovation, beginning with small pockets of innovation in technology at the industrial process level. Mainly powered by manufacturing and agriculture, innovative ways to improve system efficiency and sustainability is a long-standing tradition in Wisconsin. For example, the first commercial hydroelectric plant was built on Fox River in Appleton, Wisconsin in 1882.5 Then in 1943, Wisconsin engineers perfected the first mechanical tree planter, which was used to accelerate reforestation.6 In 1997, researchers decoded the genes of Escherichia coli (E. coli), a bacterium now widely used in the production of biofuels.7 The list of technology innovations goes on, establishing the roots of research and industry experience that has primed Wisconsin to be a rising innovation hub today.

Over the past decade, the focus on clean energy innovation has increased, and now Wisconsin is home to over 75,000 clean energy industry jobs.8 To take a closer look at Wisconsin’s energy innovation ecosystem today, the following four stories pull from expert interviews and supporting research to highlight some of the challenges and successes of this rising innovation hub.

1. Success with Leveraging Strengths in Agriculture and Manufacturing

Key Takeaway: Leveraging core strengths, such as its robust agriculture and manufacturing industries, has and can continue to drive Wisconsin’s clean energy innovation ecosystem.

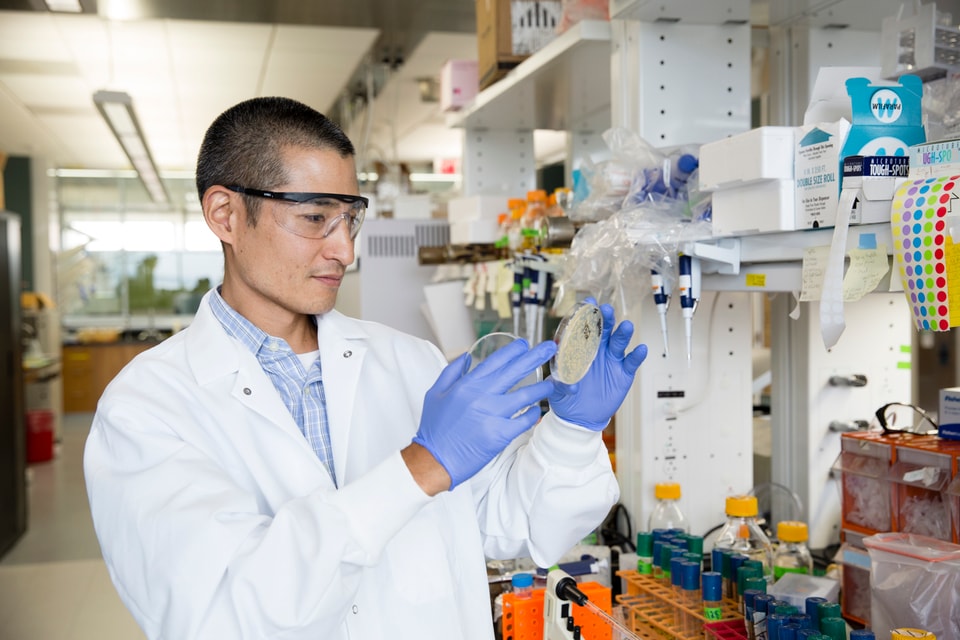

In Wisconsin, the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC) has embarked on a new phase of research and development focused on clean alternatives to transportation fuels.9 While this is an ambitious undertaking, the GLBRC has already seen 10 years of successful research, with over 1,000 scientific publications, 160 patent applications, 80 licenses or options, and 5 start-up companies. GLBRC also has the support of the Department of Energy (DOE), one of only four bioenergy research centers in the country selected to receive funding for fiscal year 2018.10

To achieve its goal of developing clean alternatives to transportation fuel, the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center is looking into producing bioenergy crops on non-agricultural lands and optimizing the field-to-product pipeline to spur the next stage of the bioenergy industry.11 (Source: GLBRC).

How Wisconsin became home to one of the country’s leading bioenergy research centers is hardly a mystery. With a strong agricultural sector contributing $88.3 billion annually to the state’s economy, the state is ripe with bioenergy resources.12 The large agricultural sector combined with its naturally fertile soil gives Wisconsin the capacity to produce more than 500 million gallons of ethanol per year from its corn crop.13 The agricultural sector also produces food waste, and combined with the manure from Wisconsin’s millions of cows and other livestock, the state could convert these bi-products into energy to meet as much as 6% of energy demand.14 The potential for bioenergy is massive given this abundance of dedicated energy crops, food waste, and manure.

Recognizing the potential for clean energy and motivated to deal with some of the agricultural waste, Wisconsin researchers have a long history with bioenergy innovation. As a result of focused research and development, Wisconsin is now home to 38 biogas electric installations, which use manure and food waste to create energy.15 One such biodigester was installed at Rosedale Dairy and supplies electricity for around 1,100 homes.16 Other Wisconsin researchers are looking for creative uses of non-food biomass material, such as one project that is developing a type of flooring from wood pulp that generates electricity when people walk across it.17 Wisconsin has shown a unique drive and ability to utilize its agricultural resources in innovative ways to provide clean power for the state.

The biodigester at Rosendale Dairy processes about 240 tons of separated solids per day in order to provide power for around 1,100 homes.18 This innovative large scale project won the Biogas Project of the Year award in 2015 for using manure to provide clean electricity. (Source: biofermenergy)

Wisconsin has shown a unique drive and ability to utilize its agricultural resources in innovative ways to provide clean power for the state.

Beyond utilizing its agricultural resources to provide clean energy, Wisconsin also has huge potential for clean energy innovation in its robust manufacturing sector. Notably, Wisconsin’s ability to innovate and manufacture sensors and controls could position the state as a leader in the technology. Sensors and controls are technologies that allow the energy system to be more responsive to change, such as weather and demand, and are a critical component to a clean energy future. Wisconsin already has over 209 companies manufacturing sensors and controls for advanced energy systems and an estimated 11,600 jobs in advanced energy sensors and controls.19 Many of these companies collaborate closely on technology innovation with the Wisconsin Electric Machines and Power Electronics Consortium, a technology center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The industry has a projected growth of about 7% annually through 2022 and could support 44,000 jobs annually if properly pursued.20 According to the American Jobs Project, by concentrating resources in sensors and controls innovation, the industry could provide substantial further economic and employment benefits for Wisconsin.21

As the state looks to expand its clean energy industry, innovation will continue to play a critical role in giving Wisconsin a leg up on competitors. Wisconsin’s ability to innovate and utilize its agricultural resources is uniquely inspiring, and the large potential to expand innovation in its manufacturing sector holds a lot of promise for the future of Wisconsin’s clean energy innovation ecosystem.

2. Strong University System Proves Vital for Innovation Ecosystem

Key Takeaway: Universities play a vital role in Wisconsin’s innovation ecosystem, from developing a skilled workforce to conducting crucial research and development.

Innovation requires researchers and research labs. This is where universities have led the charge in Wisconsin. Wisconsin is home to 85 colleges and universities, producing over 4,000 graduates in engineering and engineering technology fields per year.22 The University of Wisconsin-Madison is Wisconsin’s largest public university, one of the top research universities in the world, and essential to Wisconsin’s energy innovation ecosystem. UW-Madison is the flagship of the University of Wisconsin System, which consists of 25 other campuses. The state is also home to many private universities, the largest being Marquette University, and a robust technical college system, the largest being the Milwaukee Area Technical College. In fact, Wisconsin was the first state to develop a technical college system, giving it over a century of experience in educating a capable technical and innovative workforce.

Wisconsin was the first state to develop a technical college system, giving it over a century of experience in educating a capable technical and innovative workforce.

The state has an abundance of university programs and research centers geared towards clean energy innovation;23 however, one of the leading energy research and technology innovation institutions is the Wisconsin Energy Institute (WEI). Established in 2013 at UW-Madison, WEI supports researchers studying carbon-neutral technologies, the next generation of biofuels, as well as energy storage to support a smarter energy grid. WEI is home to several labs and research centers, including the energy storage research lab that was built in collaboration with Johnson Controls. WEI also includes the Engine Research Center, which focuses on combustion performance and reducing emissions. The work of WEI faculty and students has led to incredible technology innovations that will continue to evolve the clean energy sector.

The Wisconsin Energy Institute is one of the leading energy research and technology innovation institutions in the country. (Source: UW-Madison)

Wisconsin’s strong university system provides a skilled workforce and plays a central role in the state’s innovation ecosystem with its top research facilities and researchers. While the value of the university system in Wisconsin’s innovation ecosystem appears clear to experts working in the space, it seems not everyone in Wisconsin is on the same page. A brief background is necessary to understand this conundrum.

The UW System follows a long-standing tradition known as the ‘Wisconsin Idea,’ which is attributed to former UW President Charles Van Hise. He stated in a 1905 address, “I shall never be content until the beneficent influence of the University reaches every family of the state.”24 Van Hise, dedicated to this idea, forged a strong relationship with Robert M. La Follette, former governor and representative of Wisconsin in the House and Senate.25 This fostered a long history of collaboration between university scholars and the state government in order to create a broader impact for the surrounding communities. Collaborative efforts resulted in groundbreaking legislation, including the nation’s first workers’ compensation legislation and the public regulation of utilities.

Former UW President Charles Van Hise began the concept of the ‘Wisconsin Idea.’ (Source: UW-Madison)

Fast forward to today, UW still recognizes the necessity of working with the government, industry, and other stakeholders in order for the work of the University to succeed beyond the academic space and benefit the surrounding community. The importance of a thriving university system and the mantra of collaboration to create a broader positive impact are evident. Yet, not everyone acknowledges the value of the universities.

The ‘Wisconsin Idea’ has recently been under fire by those who do not recognize the benefits of Wisconsin’s robust university system. There has been an effort to cut substantial chunks of funding to the university system from the state government and even change the mantra.26 Former Gov. Scott Walker proposed a $300 million budget cut in 2015, which luckily received strong pushback and forced him to feign ignorance of the proposal.27 After that attempt failed, the American Legislative Exchange Council funded continued efforts from former Gov. Walker, the governor-appointed Board of Regents, and state legislators to diminish state support for the university system.28 These attacks on the ‘Wisconsin Idea’ fail to acknowledge the substantial contribution of public universities and their potential to lead Wisconsin into the next generation of innovation.

Wisconsin’s university system has been a backbone of its innovation ecosystem, conducting crucial research, housing top innovation facilities, and educating the next generation of innovators.

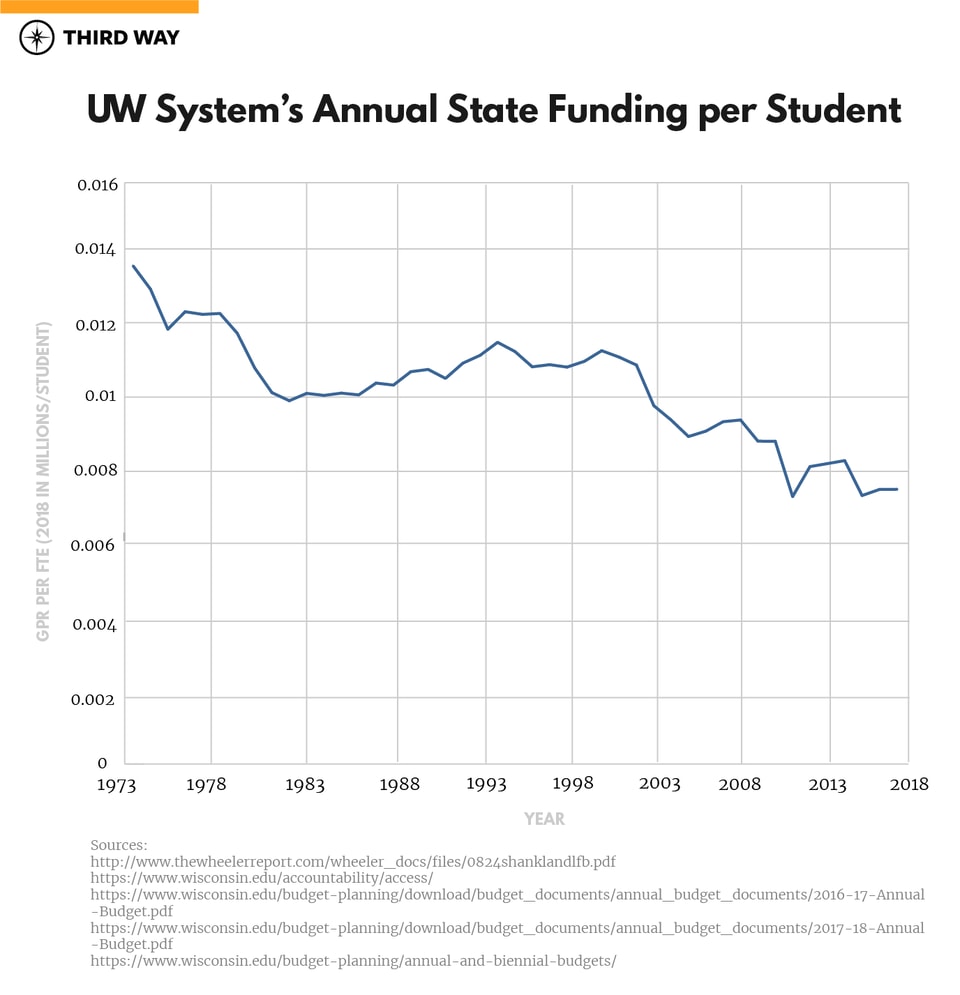

This figure shows the general purpose revenue (GPR) appropriated to the UW System by the state of Wisconsin per full time equivalent student. The amount of funding per student from the state government has declined over time, illustrating the declining appreciation of the broader impact of the universities on the wellbeing of Wisconsin.

Wisconsin’s university system has been a backbone of its innovation ecosystem, conducting crucial research, housing top innovation facilities, and educating the next generation of innovators. Despite the struggle to maintain state funding, these universities continue to create far reaching impacts for technology innovation, the state, and beyond.

3. Collaboration Leads to Accelerated and Improved Innovation

Key Takeaway: Collaboration between academic researchers, businesses, and legislators allows for innovative projects to get the funding and expertise they need to reach the marketplace.

Wisconsin’s clean energy ecosystem is rooted in collaboration between the universities, consortiums and incubators, industry leaders, national labs and administrations, independent funders, state government, and other organizations working in the energy space.

It was thanks to this collaborative mentality that UW-Madison, UW-Milwaukee, and Marquette University worked together with four energy industry leaders to establish the Mid-West Energy Research Consortium (M-WERC) in 2009 (formerly the Wisconsin Energy Research Consortium). The goal was to create a research consortium to coordinate better on energy research, tapping into the resources of Wisconsin’s over 900 energy sector companies,29 including 130 solar companies and 230 wind companies. The consortium is currently made up of 10 large research members and about 80 mid-sized companies, smaller purchasers of start-up technology solutions, and graduate student teams.

One of M-WERC’s core mission areas is technology innovation, leading to the creation of the Technology Innovation program in 2010. In the words of the Director of Technology Innovation, Bruce Beihoff, the program “combines industry insight and academic research capabilities to drive research and technology development opportunities for the energy, power and controls (EPC) industry. It goes after problems that are too tough to solve one group at a time.” The Technology Innovation program is a prime example of successful collaboration between industry leaders and universities.

Another major effort in collaboration driven by M-WERC began in 2014, with the unveiling of plans to create the Energy Innovation Center, funded with support from state and local development funds.30 The Energy Innovation Center provides a collaborative space where academic scientists, industry, engineers, and business leaders can conduct research on innovative technologies and bring them to the commercial stage. As a result of growing dedication to clean energy research, the Energy Innovation Center also became home to an incubator and accelerator31 that are helping to enhance the collaboration between clean energy researchers, industry experts, and investors. The success of the Energy Innovation Center helps solidify M-WERC as a global hub for energy research and innovation.

The federal government has supported many of Wisconsin’s collaborative efforts in clean energy innovation, mainly providing funding and expert support from the DOE and the national laboratories. While there are no DOE national laboratories or Technology Centers in Wisconsin, there is frequent collaboration.32 Additionally, funding from the DOE has been crucial. For example, the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC), previously mentioned as a leader of bioenergy research, was actually established by the DOE’s Office of Science Biological and Environmental Research program. Although based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Wisconsin Energy Institute, GLBRC has received over $267 million in DOE funding since its inception. The major success of the research center shows the astonishing progress that can be made when the federal government supports technology research.33 Despite these successes, energy innovation funding from the federal government for Wisconsin has reduced in recent years. The DOE provided only $47.3 million in FY 2017, down from $57.6 million in FY 2016. The requested amount in the FY 2018 Congressional Budget was only $12.2 million.34 The federal government is an important collaborator within Wisconsin’s clean energy ecosystem and should look to increase rather than withdraw its support.

The federal government is an important collaborator within Wisconsin’s clean energy ecosystem and should look to increase rather than withdraw its support.

These extensive efforts to collaborate and utilize a wide breadth of knowledge and resources are a cornerstone of Wisconsin’s energy innovation ecosystem. Such collaboration should be replicated and built upon, and other states could do well in following Wisconsin’s impressive example.

4. Wisconsin Clean Energy Start-ups off to a Rough Start

Key Takeaway: Clean energy start-ups need additional support in order to cross the Valley of Death and bolster the health of Wisconsin’s innovation ecosystem.

Despite university investment and industry collaborations in clean energy innovation, there is a major struggle in Wisconsin to produce start-up companies. In fact, for the past three years Wisconsin has been ranked 50th of the 50 states in start-up activity.35 While some might argue36 that less start-up activity is not necessarily an indicator of the overall health of an innovation ecosystem, there is certainly evidence that a greater number of technology-based start-ups correlates to a more robust state economy.37 As Wisconsin looks to increase its status as an innovation hub, improving its start-up environment will be critical to bringing academic research and technologies into the market.

Luckily, universities and industry members in Wisconsin seem aware of this shortfall and are working to address it. Specifically, stakeholders are looking to conquer the Valley of Death. This period between early stage research and commercialization kills off many innovations before they are able to reach their full potential. The main cause? Funding. Public sector investment is more likely to fund early-stage high-risk research, whereas private sector investment leans towards established business models that provide more secure investments. Venture capital is often used to bridge this funding gap; however, Wisconsin receives less than two-tenths of 1% of national venture capital investment.38 Funding for start-ups from angel and venture investors did double from 2015 to 2016 for a record $261 million in Wisconsin, but the numbers are still not enough to see substantial start-up growth.39 The state does have its own venture capital fund, the Badger Fund, but it is not available to clean energy innovative projects. To survive the Valley of Death, Wisconsin innovators are looking to attract more private investment and find other creative sources of funding for clean energy start-ups.

One existing source of funding for clean energy innovation that has been a lifeline for many projects is the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF). Established in 1925, WARF is the oldest tech-transfer organization in the US. WARF helps with the patenting, licensing, and commercialization of research, and works closely with UW-Madison faculty. Additionally, WARF brings in federal research funding, handing over the royalties to the university. One of the most unique aspects of WARF is that it allows researchers to retain ownership of their intellectual property while they license to WARF for help in funding for commercialization. WARF’s support of innovative projects has already led to many successful start-ups originating from UW-Madison.40 For example, the start-up Virent found an innovative use for biomass, creating a way to convert biomass-derived sugars into products such as gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and chemicals used for plastics and fibers.41

Beyond the support of tech-transfer organizations such as WARF, Wisconsin innovators can receive funding from accelerators, competitions, federal grants, state grants, and not-for-profits.42 These financial opportunities are not yet enough to support the thriving energy innovation hub that Wisconsin is primed to become, but there are plenty of signs that investment in the clean energy industry is set to increase. Madison has a rapidly growing tech scene that is attracting more attention. Wisconsin has affordable living costs for employees, high job creation rates, lower initial start-up costs, and a dedication to creating collaborative environments. The Brookings Institute ranked Madison as one of the top cities in growth rate for advanced industries.43 The full potential of the innovation space in Wisconsin can be realized with the proper mix of funding from both private and public investors.

Wisconsin has affordable living costs for employees, high job creation rates, lower initial start-up costs, and a dedication to creating collaborative environments.

To aid in the struggle to secure funding and support entrepreneurs, state policies can play an important role. One example is with restrictions on non-compete contracts. In Wisconsin, the prevalence of non-compete clauses in employee contracts could be a deterrent for some entrepreneurs.44 Silicon Valley innovators, on the other hand, benefit from California’s limited non-compete contracts. Non-competes have been found to limit entrepreneurship and the dissemination of academic knowledge and innovative ideas.45 If Wisconsin wants to attract more spin-offs and keep entrepreneurs within the state, then it should loosen the grip on non-compete contracts.

On the federal level, U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisc), a strong advocate for innovation in Wisconsin, reintroduced the Small Business Innovation Act in 2016 to incentivize further venture capital investment in small businesses. The bill also included authorization for a separate fund for small business investment companies to support biotechnology and clean energy, something the state’s venture capital fund does not cover. More recently, she introduced the Support Small Business Start-Ups Act to provide tax relief in order to make it easier for new businesses to develop, something that would help entrepreneurs looking to cross the Valley of Death.46

While start-ups may be a weak point in Wisconsin’s clean energy innovation ecosystem, there are already efforts underway to build support for them and indicators that Wisconsin is set to attract more entrepreneurs and investors.

A Bright Future for Innovation in Wisconsin

Wisconsin may have some challenges ahead in growing its clean energy sector, but it has already developed strong roots for a successful innovation ecosystem. Its robust agricultural and manufacturing sectors provide exciting resources and opportunities for further development of clean energy technologies. Its strong university system, in collaboration with industry leaders, provides the knowledge and expertise needed to advance innovative ideas and bring them into the market. Further financial support for researchers and start-ups will be crucial, but there are many indicators of increased investment. It is time for Wisconsin to fully embrace clean energy and build out its innovation ecosystem to establish itself as a leader in the field.