Report Published February 17, 2016 · Updated February 17, 2016 · 39 minute read

All State Marijuana Laws Are Not Created Equal

Sarah Trumble, Lanae Erickson, & Tyler Cole

When voters in Ohio recently rejected a ballot initiative that would have legalized marijuana, even some of the most fervent marijuana advocates cheered. They referred to the measure known as Issue 3 as an “oligopoly,” “a transparent get-rich quick scheme,” and even some phrases that can’t be repeated in polite company.1 They were right: it was a poorly-designed regulatory scheme, and if it had passed, it would have put the financial interests of its backers ahead of good policy. Yet the federal government’s current stance toward marijuana legalization in the states does nothing to recognize successful policies or distinguish them from poorly written ones. And some of the legislation that has been introduced ostensibly to fix this problem would actually make it worse—rendering the federal government completely unable to use its power to dissuade states from enacting ill-advised or even potentially dangerous marijuana laws.

According to a recent report by the Drug Enforcement Administration, 80% of states have legalized some form of medical marijuana, and 23 have broadly legalized marijuana use for medical purposes. Four of those states, along with the District of Columbia, have also legalized marijuana for recreational use. These states are establishing their own regulatory systems and rules in wildly different ways. Some states have set up systems that are highly-regulated from seed to sale, while others are passing policies that risk creating a wild west of marijuana. Yet because marijuana remains illegal under the federal Controlled Substances Act, there is no federal role in the oversight of these state regulatory structures, and federal law treats them all the same.

The fact of the matter is that there are legitimate federal interests at stake in the debate about whether and how to legalize marijuana. And unless we are going to abolish the laws of 23 states (or more) and return to a previous era of complete prohibition, we must enable the federal government to set up policy guardrails to steer state regulatory systems in the right direction. To help determine what those guardrails should look like, it is helpful to examine the different ways states are effectively regulating—or failing to regulate—legal marijuana. In this memo, we examine six important federal interests implicated by marijuana legalization and explain the vastly different approaches states have taken to protect them. A review of these laws clearly demonstrates that not all state marijuana legalization systems are created equal.

FEDERAL INTERESTS AT STAKE IN MARIJUANA LEGALIZATION

The six federal interests covered in this report were chosen because of their importance in both federal policy and public opinion. Four of them—drugged driving, use by minors, diversion to other states, and criminal enterprise, violence, and guns—come directly from the second “Cole Memo,” in which the Department of Justice listed its eight federal prosecution priorities. We combined several different pieces into the criminal enterprise, violence, and guns section because so many of the actions states have taken to combat them are intertwined. And we left out others, like the growing of marijuana on federal land, because the states have not taken as wide of a variety of approaches to regulating them and because the federal government has a clear nexus on which to act on them regardless of whether marijuana remains illegal federally or legislation is passed that cedes policy control to the states.

We review policies toward drugged driving and use by minors first, not only because they are among the most important and challenging to regulate, but because they are the two most pressing concerns weighing on the minds of voters in the marijuana middle, who are conflicted about marijuana and feel torn about whether it should be legalized nationwide. In our recent poll, 65% of voters worried that “increasing access [to marijuana] will cause more drugged driving and make our roads more dangerous.” And 57% worried that loosening marijuana laws would “increase use by children, sending a message that it’s safe, and would allow sellers to market marijuana-laced candy to kids.” If marijuana advocates want to end the federal prohibition, they will need to persuade the marijuana middle—and they can’t do that without addressing the very real dangers of drugged driving and youth use.

The final two interests, consumer protection and regulating marijuana advertising, are included because of the difficulty states who have already legalized are having with effectively regulating them. Tainted marijuana was in the headlines almost weekly in Colorado last year, resulting in recalls, destruction orders, and executive orders to deal with the problem. Newspapers ran in-depth investigations, and parents of young children who use medical marijuana to reduce seizures often found they were not sold the product they were promised. Meanwhile, anti-marijuana advocates have scared parents with the specter of marijuana billboards across from schools and churches, and some communities have had to take it upon themselves to pass rules restricting how and where such advertisements can be seen.

But these six interests all have two things in common: 1) the federal government has a very real interest in making sure they are being smartly regulated, and 2) should Congress either do nothing or pass legislation that hands all control of marijuana policy over to the states, the federal government’s ability to encourage states to pass the smartest and most effective regulations will be severely hampered.

In each section, we look at a variety of states and the different ways in which they are approaching these interests. States may be the laboratories of democracy, but even if they come up with different ways to handle the issues at hand, the federal government needs to have the ability to incentivize or guide those policies in a way that ensures national interests are protected.

Drugged Driving

Discouraging drugged driving is a major priority both for regulators and for voters in the marijuana middle, yet exactly how to best accomplish that goal is a complicated question involving science that’s not yet settled. It is clear that intoxication in any form can impair driving skills—slowing reaction time, decreasing motor coordination, and impairing spatial judgement. After alcohol, marijuana is the substance most frequently identified in those driving under the influence, with 12.6% of drivers testing positive for THC (the active ingredient in marijuana) in the 2013-2014 roadside survey.2 Just as it is in the national interest to reduce drunk driving, it is similarly important to the general welfare that states have in place regulations to detect and prevent drugged driving—especially if marijuana is legal for use in their state. But if Congress cedes federal control of marijuana policy to the states, the federal government will have little influence over the quality or even existence of state laws regulating this potential danger on our nation’s roadways.

The Policy Solution

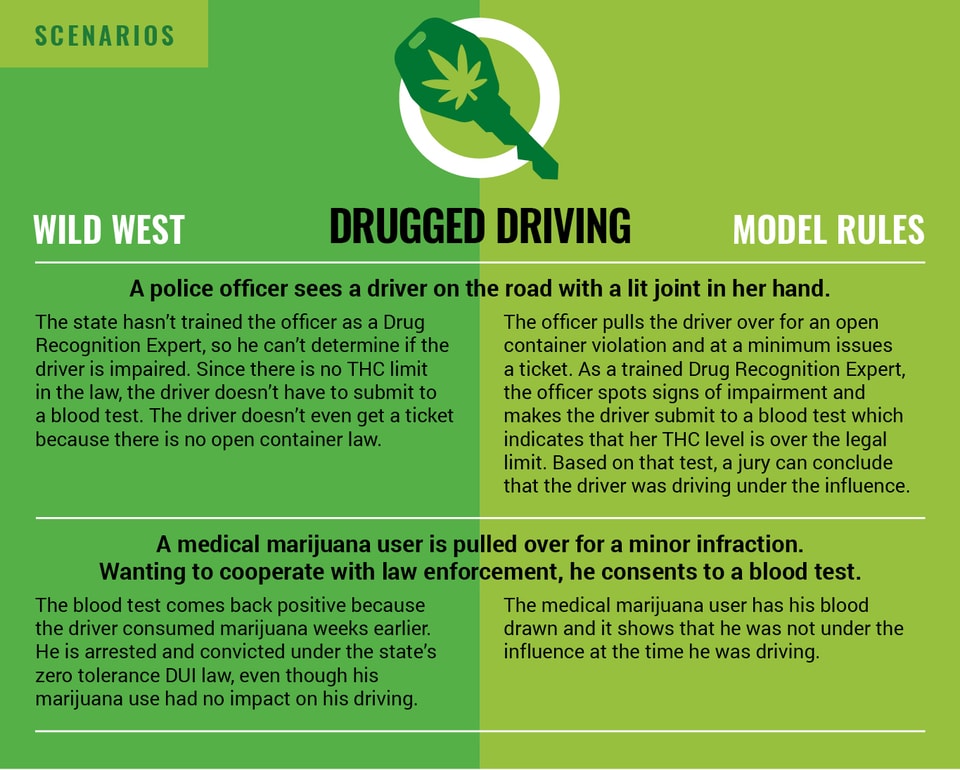

Currently, it is illegal in every state to drive while impaired by marijuana.3 However, some states choose to enforce this proscription by making it illegal for someone to drive with any amount of the drug in their system. A zero tolerance law is unrealistic and counter-productive in states that have legalized marijuana use because small amounts of marijuana can remain in a person’s system for days or weeks at a time, long after the impairing effects of THC have worn off. A zero tolerance limit could effectively make it illegal for a medical marijuana user to drive to work on Monday morning after consuming marijuana on Friday night. Instead, the best way to keep the roads safe is to make it illegal to drive with a specific, measurable, and impairing amount of THC present in your system. The limit should be set so that a person can drive with a small amount of THC in their blood—a level that is not dangerously impairing—but so that driving with too much is illegal, similar to laws against driving with a blood alcohol content over .08.

But at what point marijuana impacts driving is up for some debate. Various studies point to a reasonable limit of between five and 13 nanograms of THC per milliliter of blood.4 Since the science is still out in some ways on this question, the specific limit that a state chooses is not as important as the fact that it chooses to establish a limit, so that there is a test that can be measured and applied objectively. The most common limit is five nanograms per milliliter, which is used by Colorado, Montana, and Washington, while Nevada has a limit of two nanograms.5 And there is another layer to this kind of policy: use of marijuana over an extended period of time, such as by a medical user, can lead to elevated levels of THC without the associated impact on driving skills. To ensure that the chronically ill or other regular users are not unfairly captured by a limit, the best laws establish that driving with a THC level above the limit creates a permissible inference or a rebuttable presumption that the driver was driving under the influence—a presumption that the driver can then attempt to disprove in court.

Since drivers become more impaired when using both marijuana and alcohol together, states can and should also impose a separate, lower limit for drivers with both intoxicants in their systems. To help with effective enforcement, states should also adopt a clear “open container” law, prohibiting the consumption of marijuana while the car is being driven and the presence of unsealed containers of marijuana in the passenger compartment of a vehicle, comparable to rules about alcohol in cars.

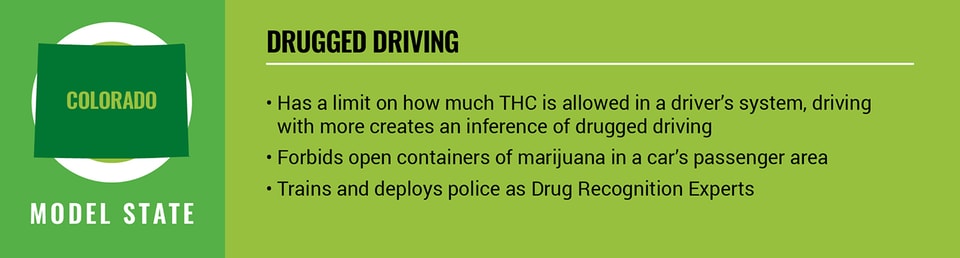

The Current Landscape

Colorado is a model example for states looking to ensure that marijuana legalization doesn’t create a drugged driving problem. Colorado has enacted a limit of five nanograms of THC per milliliter of blood, and driving with a higher amount of the drug present in your blood triggers an inference of driving under the influence. That means in the event of a trial, a jury would be allowed—but not required—to conclude that because the THC level was above the limit, the driver was impaired, but the driver would also have a chance to prove she wasn’t.6 Colorado doesn’t have a separate lower limit for when a driver has both marijuana and alcohol present in their system, but given the relatively low THC limit, that is not a serious shortcoming. Colorado also has a vehicular open container law, prohibiting unsealed containers in the passenger area of a vehicle.7

Beyond merely establishing regulations, Colorado trains its law enforcement officers to know when a driver is impaired by drugs, and many are Drug Recognition Experts, specially trained to “detect physical signs of drug impairment.”8 If a police officer has reasonable grounds to believe a person is driving under the influence, the officer can require that driver to take a chemical test. Refusing to take the test results in the driver immediately losing his or her license for a year, among other possible consequences. The Colorado Department of Transportation has also been working to raise awareness of the impact that marijuana has on driving, as well as studying how the drug affects the ability to do so safely.9 Many of these smart policies—including drug awareness education and law enforcement training—are actually funded at least in part by the tax revenue the state of Colorado now earns because it legalized its market.10

Unfortunately, not all states have done as robust a job of regulating drugged driving as Colorado, and many fall outside of what federal guardrails should permit. For example, California has an open container law but no numerical limit on THC in a driver’s blood.11 And though Montana has a limit of five nanograms per milliliter, it does not have any open container law—which could allow a driver to legally smoke marijuana while driving, so long as their level of THC is below the legal limit.12 Of the 23 states that have legalized marijuana for medical or recreational use, 14 have no specified THC limit and 17 do not have vehicular open container laws. Five of those states have zero tolerance THC limits. For instance, in Delaware, a state that has legalized medical marijuana, it is illegal to drive with any amount of marijuana in your system, regardless of any impact on performance, and having marijuana in your blood up to four hours after driving can lead to a DUI.13 That means that someone who treats their symptoms with a single dose of marijuana one afternoon and drives the next day or the next week could potentially be arrested and convicted of driving under the influence. Even if the driver was fully obeying state traffic laws and their marijuana use had no impact on their driving, if they had to have their blood tested after getting rear-ended or skidding on black ice, the presence of any THC could cause them to go to prison for a year and be fined $1,500.14 Worse still, the presence of any marijuana metabolites—inactive ingredients which do not have any impact on your ability to drive—also violates the law. This is basically equivalent to being convicted of a DUI because you are driving with a beer belly.

Use by Minors

A common question raised in this debate is what impact—either positive or negative—legalization and regulation will have on minors’ ability to obtain marijuana. No one thinks that legalizing medical marijuana for patients in need and recreational marijuana for adult use should make it easier for kids to get their hands on marijuana. Many studies show that early and continued use of marijuana among adolescents could potentially have serious negative consequences on brain development, memory, cognition, and academic success.15 But done right, legalization and smart regulations can actually make it more difficult for minors to get marijuana (after all, drug dealers aren’t renowned for checking IDs). In fact, data show in at least one state that implementing good regulations actually leads to a decrease in teen use.16 However, if Congress passes a bill that shifts all control of marijuana policy to the states, the federal government’s hands will be tied when it comes to steering states towards these types of effective regulations. Even under the status quo, where the federal government is turning a blind eye to the conflict between state and federal marijuana law, it has no real means of either distinguishing between good policies in this area and those that are lacking or pushing states to better regulate minors’ exposure to marijuana.

The Policy Solution

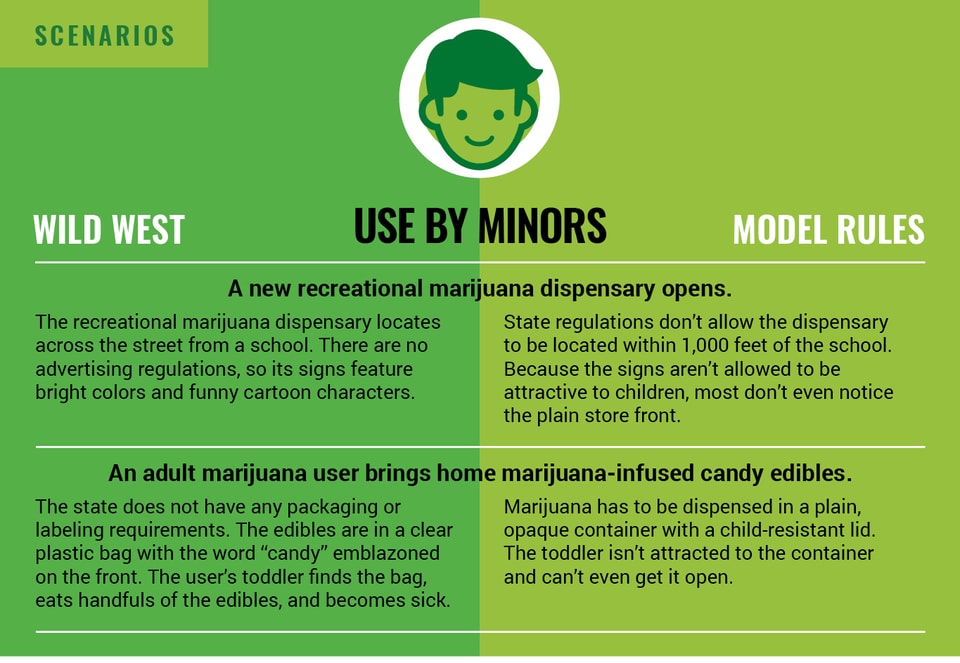

It is currently illegal in all 50 states for minors to use marijuana recreationally, but there are additional safeguards states should employ to ensure they are preventing youth access to the drug. States should explicitly make it a crime for an adult to transfer recreational marijuana to a minor, like the laws prohibiting adults from buying beer for kids. Marijuana should be kept away from schools and other child-centered facilities. States should require enforcement mechanisms similar to alcohol or tobacco: no minors in dispensaries, mandatory ID checks, and strict liability for sales to minors. In states that have only legalized medical marijuana, a robust medical registration process can provide a similar level of protection. To reduce the risk of accidental consumption, marijuana containers should be child-resistant, opaque, re-sealable and clearly indicate that the product contains marijuana—especially for edibles. Packaging should not be intentionally enticing to children, and—similar to laws about tobacco—advertising shouldn’t be allowed to target kids or be located near children’s facilities.

The Current Landscape

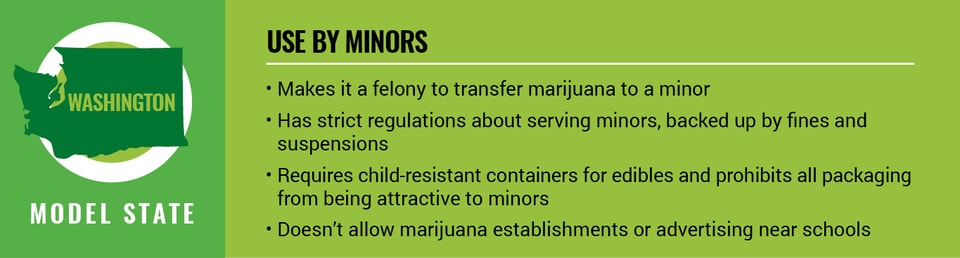

Washington State’s regulations provide a good, largely comprehensive model for states seeking to prevent minors from using or accessing recreational marijuana. For one, it is a felony in Washington for an adult to give marijuana to anyone under 18 years of age, unless they are a patient in the medical marijuana program.17 While the state’s medical marijuana program is available to minors with medical needs so long as their parents are involved, a recent change to the law requires physicians to take a more involved approach if they are authorizing medical marijuana.18 Minors may not be present at recreational marijuana facilities, and if an establishment allows them to be on the premises, it is subject to fines.19 Each sale of recreational marijuana should be accompanied by an age verification and ID check, and selling marijuana to a minor can lead to fines or license suspension or revocation—whether the seller did so intentionally or not.20

Washington also requires that edible products and marijuana concentrates are dispensed in child-resistant packaging, and if there is more than one serving in the package, each serving must be packaged individually in childproof packaging.21 The state prohibits labels and advertising that depict minors, are “designed in any manner that would be especially appealing to children,” or feature “[o]bjects, such as toys, characters, or cartoon characters.” Advertising cannot be within 1,000 feet of any “school grounds, playground, recreation center or facility, child care center, public park, library, or a game arcade admission to which it is not restricted to persons aged twenty-one years or older.”22 Lastly, there must be material included with all marijuana dispensed that features a warning that the product is intended for use "only by adults twenty-one and older” and to “[k]eep out of reach of children.”23

But Washington is not the only state doing a good job of preventing youth access to marijuana—some other states have regulations that go even further than Washington in some ways or present good examples of alternative policy solutions. In Oregon, establishments can only advertise if they have reliable evidence showing that only a small portion of the audience is reasonably expected to be under 21.24 Colorado allows recreational and medical marijuana to be sold at the same location but requires either a physical separation between the two or that the medical facility only service customers over 21.25 Massachusetts and Minnesota both require product labels warning that the product should be kept away from children, and Colorado requires edible products to have a state-provided symbol indicating marijuana imprinted directly on the product.26 In Hawaii, unlawful delivery of marijuana to a minor is a Class B felony, punishable by up to ten years in prison.27

Nearly every state prohibits the possession of marijuana on school grounds and school buses. Many states place zoning restrictions on marijuana establishments or forbid them from being too close to schools or other child-centered facilities, but the definition of “too close” can vary widely. Maryland, where medical marijuana is legal, does not have laws on the books setting any sort of distance limit, but the state has to approve the location of each establishment.28 Montana did not codify any location restrictions in its state legislation, but it allows local jurisdictions to regulate marijuana facilities and ban marijuana storefronts.29 New Mexico prohibits marijuana establishments within 300 feet of a school, church, or daycare.30 Arizona and Maine opt for a distance of 500 feet from schools, while Massachusetts applies that distance to schools, daycares, and “any facility in which children commonly congregate.”31 California requires a distance of 600 feet; Hawaii, 750.32 The most common distance is 1,000 feet, which is used by 12 states. Illinois requires cultivation centers to be even farther away at 2,500 feet, while Washington allows local jurisdictions to reduce the default limit of 1,000 feet (around child-centered facilities) to 100 feet, except around schools and playgrounds.33

The good news is that good regulations appear to be working. Colorado has a system similar to that in Washington, and according to the 2013 Healthy Kids Colorado Survey, there has actually been a small decrease in both the percentage of high school students who had ever tried marijuana and who had used it in the last month post-legalization.34 However, several states fail to meet the mark. For example, California does not have any rules on advertising, even when it comes to children. Rhode Island bans smoking marijuana on school grounds and in school buses, but its law could be read to potentially allow possession of marijuana at those locations.35 Montana doesn’t have any packaging or labeling requirements. Clearly, there is much room for improvement.

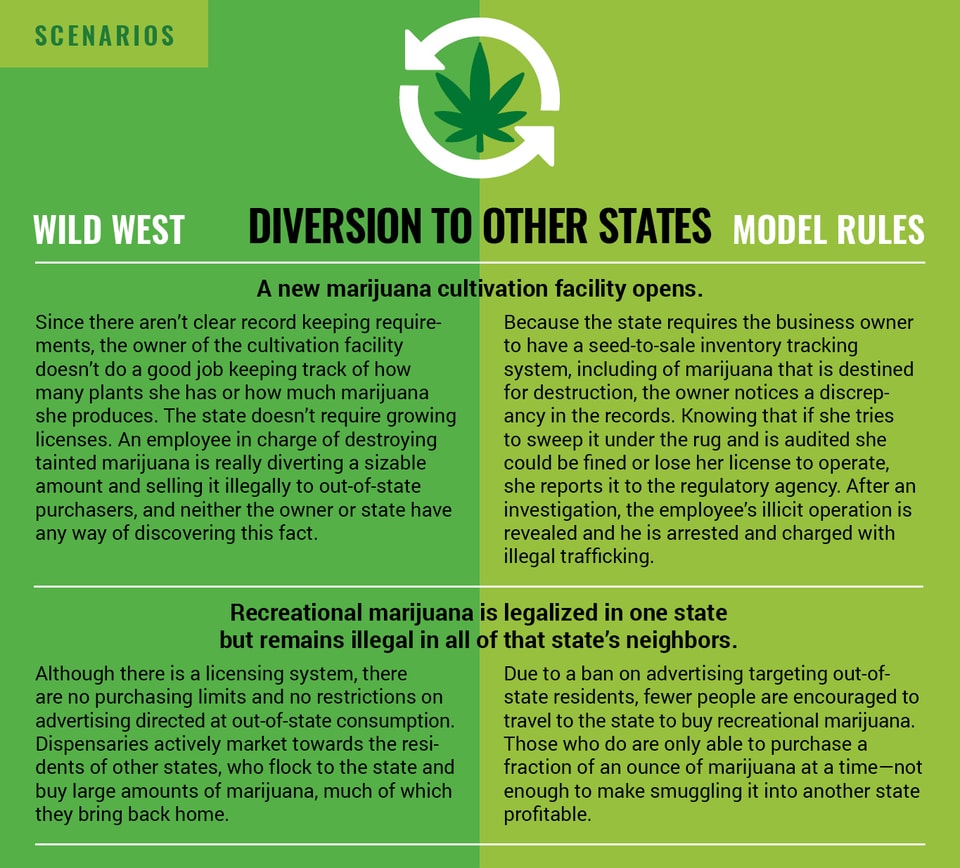

Diversion to Other States

One question of particular importance to the federal government is whether state regulatory systems will allow diversion of marijuana from states where its possession and use is legal to states where it is illegal, states with different legalization rules, or even into other countries with different laws. On this issue in particular, there are national implications as well as federalism concerns. We live in a global world where borders mean less today than ever before, and that is doubly true for borders between states, rather than nation-states. Marijuana from Colorado, where it is legal, has been found in states as far away as Illinois, New York, and Florida.36 Nebraska and Oklahoma are suing Colorado on the grounds that diversion of legal marijuana from Colorado into their states is increasing drug crime. A state that has chosen not to legalize marijuana should not be forced to shoulder the costs of doing so—in enforcement or potential consequences—just because a neighboring state voted the other way.

Diversion is difficult to measure, but even advocates who believe it to be rarer than Nebraska and Oklahoma claim should recognize that poor state regulation of diversion could make Americans think twice about legalization. Seeing marijuana from one state spread nationally—and potentially internationally—would raise serious concerns for the marijuana middle. While they support allowing the federal government to grant safe havens to states that have chosen to legalize, these voters would strenuously object to legalization anywhere if illegal diversion into their state was an anticipated consequence. The federal government needs to have the ability to establish guardrails for states to encourage them to pass robust laws blocking diversion. Unfortunately, neither current policy nor most proposed bills introduced in Congress allow it to do so.

The Policy Solution

To help control diversion into states that do not have legal marijuana, states should tightly regulate production licensing. Most states require producers to be licensed by the state before they can grow or sell marijuana and to provide the state with information on the location, ownership structure, and scope of the operation. Consumers should also be subject to purchasing limits. States should apply harsh criminal sanctions for interstate trafficking, and a negligent marijuana establishment should face consequences if it is determined to be the origin of trafficked marijuana. Destruction of marijuana should also be monitored to ensure one man’s trash doesn’t become another man’s treasure, like under Illinois law, which requires marijuana establishments to file information with the state when they destroy plants or products and to keep those records of destruction for five years.

States may also want to consider entering into cooperative agreements with federal law enforcement agencies to combat trafficking both interstate and internationally. Those states that are close to federal borders in particular should designate rules and devote enforcement resources to assist the federal government in protecting the border—keeping illegal marijuana from entering the country and legal marijuana from leaving it.

The Current Landscape

Oregon is a model for how states should respond to the threat of diversion. In Oregon, businesses that wish to grow marijuana must apply for and obtain a cultivation license, and must submit details about the proposed growing operation.37 Marijuana businesses must have a “seed-to-sale” inventory tracking system maintained by the state for all marijuana, in which marijuana is tracked from the seed that grew the plant up to the point of sale to a consumer—even for marijuana that is ultimately destroyed rather than sold.38 Customers may only purchase a single ounce of marijuana per transaction.39 Advertising cannot encourage transportation of marijuana across state lines, and it is a felony if an establishment or an employee of an establishment sells marijuana out of state.40

Effective inventory systems can come in many varieties. Seed-to-sale tracking is used in several states beyond Oregon, including Colorado, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Washington.41 States also use other tactics to prevent diversion. In some states where medical marijuana is legal, such as Arizona, Massachusetts and Montana, patients are required to pledge that they will not divert marijuana to ineligible persons.42 Minnesota dispensaries must label their product with a warning stating that transfer to another person can lead to a patient losing his or her registration.43 Good rules against diversion can work. In fact, earlier this year Colorado won indictments against 32 people accused of being involved in a massive scheme to illegally grow unlicensed marijuana in Colorado and ship it out of state.44

As an example of what should fall outside of federal guardrails, for years California has essentially had no purchasing limits or inventory controls, along with anemic dispensary licensing requirements. Dispensaries have to file for regular business licensing and operate as a non-profit, but nothing beyond that is required. The test for determining whether a business is operating properly in the state is whether they could make an argument that they were serving as the growing source for legitimate medical marijuana users. While its laws are currently lacking, it should be noted that California recently passed legislation which would put a new regulatory system in place by 2018 that could remedy many of these existing flaws.45

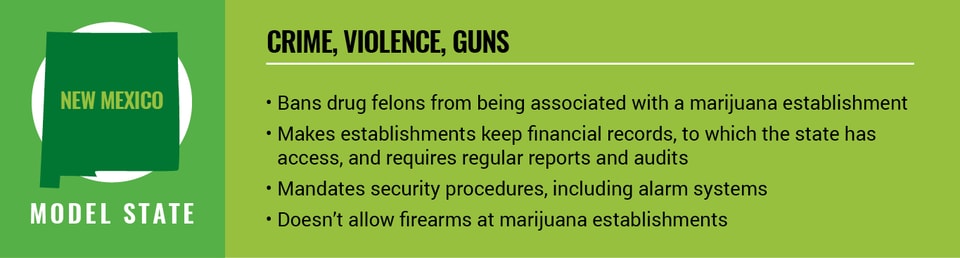

Crime, Violence, and Guns

How marijuana legalization affects crime rates depends on the way in which it is regulated. The sale of illegal drugs—a list that until very recently in every state included marijuana—is strongly associated with gangs and other criminal enterprise in this country. In fact, according to the U.S. Drug Czar, marijuana is currently the drug most often linked to crime in the United States.46 And the problem is not just confined within our borders. The Southern border is home to a heavy “guns out, drugs in” trade that finances criminal activity both in the United States and abroad, and the U.S. is the biggest market for international drug cartels.47 However, done well marijuana legalization could actually reduce threats of violence and crime, and it should be a national priority to ensure that if states choose to legalize and regulate marijuana, they do so in a way that prevents gangs, cartels, and criminals from profiting from legal marijuana markets. Unfortunately, so long as the federal government can’t establish guardrails for state regulatory schemes, it can’t incentivize them to pass strong and effective laws to ensure legalization leads to less, not more, violent crime. That’s the problem with both the status quo and with proposals to simply remove marijuana from federal jurisdiction.

This issue should be a concern not only for the federal and state governments and those drafting state regulations, but also for those advocating for broader legalization. Unless and until cartels and guns are effectively cut out of marijuana markets, those markets will be magnets for crime and violence, making them dangerous places to be a distributer, consumer, or patient. Criminal enterprises could also defraud states out of potential tax revenue, which could be a major setback as that revenue stream is persuasive to many policymakers considering legalization. In fact, unless states do a good job of writing their regulations, many of the rationales advocates rely on could be undercut substantially in the minds of both the public and policymakers.

The Policy Solution

One major way that states can use legalization to crack down on criminal enterprise and the threat of violence or the use of firearms in marijuana markets is via a strict licensing process for commercial operations and medical marijuana businesses. States can and should require that business owners, officers, and employees are not affiliated with a criminal enterprise or gangs and prohibit people with certain kinds of criminal records from owning or working in the industry. To limit the diversion of revenue into the coffers of criminal organizations, marijuana establishments should be required to keep detailed financial records that the government can inspect at any time, with or without notice. Additionally, to prevent legal marijuana operations from sparking violence, states should require that marijuana facilities have adequate security systems and forbid the possession of firearms on the grounds of marijuana dispensaries.

But current federal law doesn’t just fail to support states that want to regulate well—it actually requires their legal marijuana markets to operate in unsafe environments by cutting off access to banking services. That means marijuana businesses are forced to function on an all-cash basis, making them magnets for crime and putting their communities at risk. The federal government needs to do more than just offer states guardrails for safely regulating their markets—Congress also must pass legislation to end the banking ban.

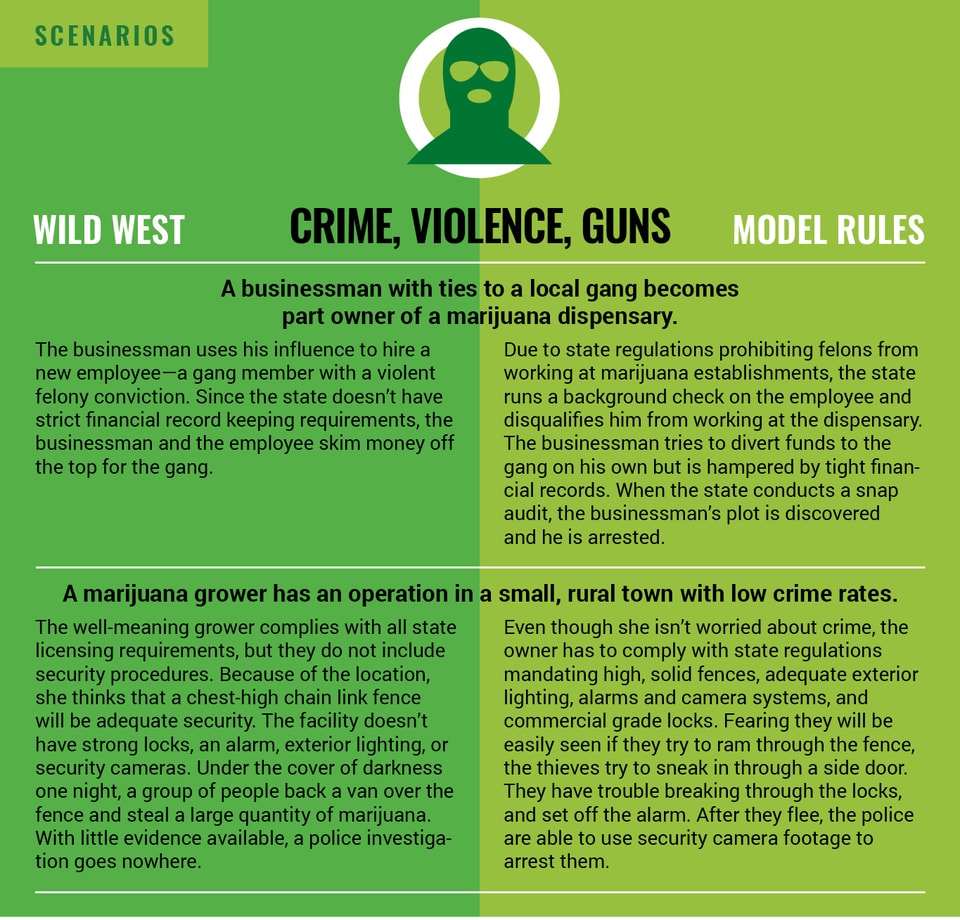

The Current Landscape

New Mexico provides a good model specifically for regulations dealing with criminal enterprise, violence, and guns and legal marijuana, though other elements of their legalization system may be lacking. Marijuana establishments must apply for operational licenses from the state, and no person “associated” with an establishment can have been convicted of a drug felony, unless the sentence has ended at least five years earlier. Multiple felony drug convictions permanently disqualify an individual, as does a single conviction for trafficking, distribution, or distribution to a minor.48 Outside of the legal medical marijuana system, possessing a small amount of marijuana is a misdemeanor, so a conviction would not disqualify someone from working in the medical marijuana industry.49 Establishments that grow and sell marijuana must be non-profits, and must keep detailed sales records in a state-approved format, which the agency can review on request. On top of that, establishments must submit quarterly reports to the state and be audited yearly by an independent CPA.50 New Mexico requires that applicants for a license to operate a marijuana establishment have a written policy to address security, safety, and crime, and keep records showing that staff has been trained on the policy; the policy and training proposal are a factor in whether the state will grant a license.51 The regulations specifically require a “fully operational security alarm system” and establishments must attest that no firearms will be permitted on site.52

A majority of states that have legalized marijuana for medical or recreational use prohibit anyone convicted of a drug felony from working in the industry, although there are a variety of approaches. Illinois doesn’t allow board members or officers of marijuana businesses to be felons of any kind or even to have been convicted of a gambling crime.53 New York doesn’t allow dispensaries to hire employees who are drug felons into positions which will come into contact with marijuana, unless ten years or more have passed since the end of that person’s sentence.54 Arizona prohibits violent felons and non-marijuana drug felons, while Maine and Rhode Island prohibit drug felons unless the felony was for activity that would be legal under the states’ current marijuana laws.55

States also utilize a variety of record keeping requirements—some more robust than others. Alaska requires that marijuana-related businesses open their books to the state upon request.56 Many states require business applicants to submit financial backgrounds. Nearly every state has security requirements for dispensaries and cultivation sites. Particularly thoughtful are Oregon’s detailed requirements, including security cameras, commercial grade locks, panic buttons, and tall fences.57 In Connecticut, the state can even require a supervised watchman if a dispensary raises certain security concerns.58

Some states have additional requirements to reduce the likelihood of criminals infiltrating their legal marijuana market. To prevent criminal organizations from easily placing their members within marijuana establishments, Colorado requires owners of recreational marijuana businesses to have been residents of the state for at least two years.59 Agents of marijuana establishments in Maryland are required to register with the state and are issued identification cards.60

There is evidence that these policies work. Colorado—which has among the most robust policies—has seen a notable drop in crime following the legalization of recreational marijuana. The homicide rate fell by 15%, burglary by 7.9%, robbery by 5%, and all crime by 2.5%.61 Violent crime in Denver, the heart of Colorado’s recreational marijuana market, fell 2.2% in 2014, while burglaries dropped by 9.5% and property crimes by 8.9%.62

On the other end of the spectrum, some states have implemented systems that are lacking sufficient regulation to ensure that criminal enterprise, gangs, violence, and firearms are kept out of legal marijuana markets. For years, California has had essentially no regulation of marijuana establishments, and storefront dispensaries operated with basically no oversight (but as previously mentioned, the state is planning to have a new, and hopefully stronger, regulatory system in place by 2018).63 While nearly all states have some sort of applicable security requirements, most do not prohibit firearms on the premises of marijuana dispensaries.

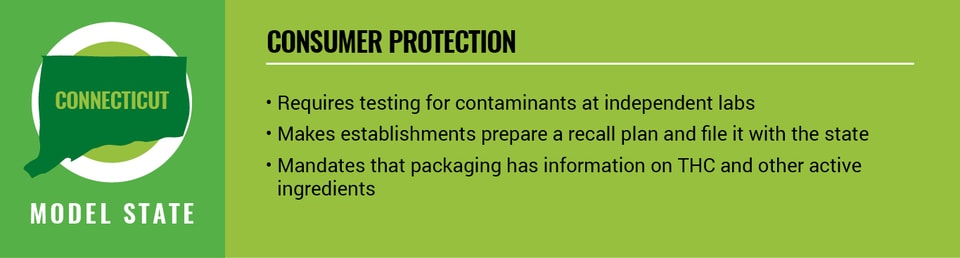

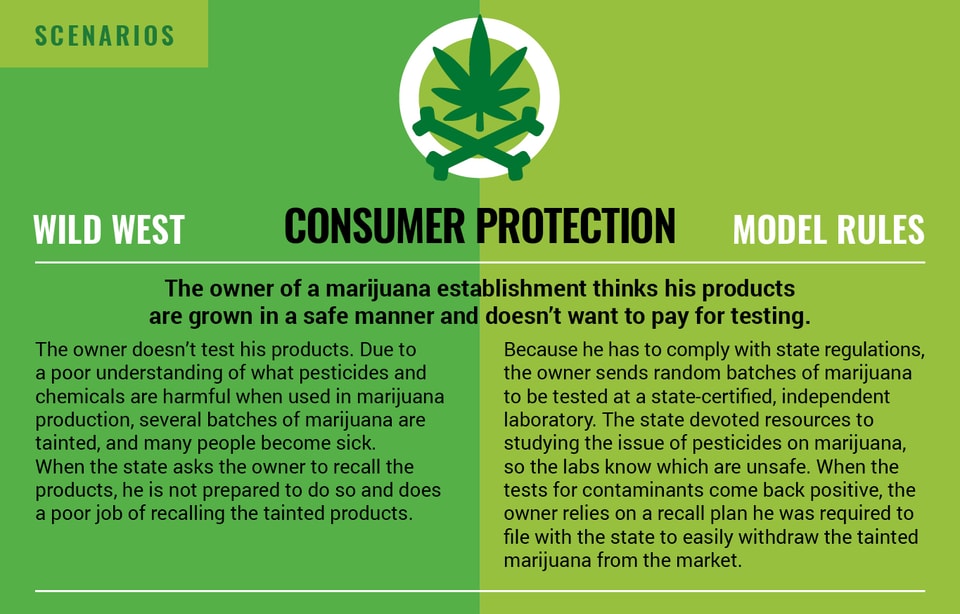

Consumer Protection

Like any product intended for human consumption, legal marijuana raises questions about consumer protection. How can the federal government help states ensure regulatory systems provide consumers with adequate information and protect them from tainted marijuana? Marijuana is a drug that changes how people think and feel while under its influence, and if consumers do not know what they are consuming or whether it has been contaminated, they could bring harm to themselves or others. New users may not know how much THC to expect in a certain product or may treat an edible like it is regular food and accidently ingest far more THC than they meant to.

Marijuana is an agricultural product, but because it is illegal under federal law, the Environmental Protection Agency is unable to issue recommendations regarding safe pesticide usage. No pesticide has been tested on or approved for use on marijuana plants by the Agency, and it is a violation of federal law to use pesticides for off-label applications.64 Ultimately, this is a problem only the federal government can resolve, but this lack of information and the inability to use tested and safe pesticides legally also significantly hampers states’ abilities to safeguard their own markets. That has led to the recall, quarantine, and destruction of thousands of plants and edibles in Colorado.65 A recent study by the Cannabis Safety Institute found that many marijuana-infused edible products, like candy or baked goods, contained higher levels of pesticides than what is allowed on other edible or smoked goods—and even some pesticides that aren’t allowed on any food crops.66

But pesticides aren’t even the only problem. Marijuana can develop mold or be contaminated by E. coli depending on the conditions in which it is grown, dried, and stored.67 A grow site or irrigation system may expose the plants to heavy metals or microbiological contaminants. Everyone has heard stories of marijuana laced with other, more dangerous drugs, or even rat poison. Legalization can make marijuana safer—but to ensure that's the case, states need regulations that protect legal users from unsafe or tainted products.

Furthermore, due to the ways states package and sell edibles, it may be difficult for consumers to determine proper dosage, leading to overdoses like the one Maureen Dowd detailed in The New York Times after eating a candy bar that unbeknownst to her contained 16 servings.68 States need to establish smart and effective regulations to protect consumers, and the federal government needs to have the authority to establish guardrails that will help them do so. But with current policy effectively asking the federal government to stick its head in the sand and advocates pushing Congress to cede all control to the states, there is little opportunity to incentivize states to prioritize consumer protection.

The Policy Solution

States should require marijuana establishments to submit samples to an independent lab to test for potency, contaminants like heavy metals, pesticides, molds, and bacteria, and to ensure the marijuana has not been laced with any other drug or dangerous substance. The state agency should either have a program for recalls or require establishments have written policies and protocols for recalls, preferably on file with the state government. Product labels should give consumers information on what type of product they are buying and how much THC it contains. Edibles should be sold either in single-servings or packaged in ways that makes it clear how much should be consumed at one time. That is all in addition, of course, to the need for federal action allowing the EPA to provide states the necessary clarification and recommendations for safe pesticide usage.

The Current Landscape

Connecticut has strong regulations aimed at protecting consumers from tainted marijuana: all legal medical marijuana has to be batched before sale and is randomly tested by an independent laboratory for “microbiological contaminants, mycotoxins, heavy metals and pesticide chemical residue.”69 The marijuana must be held until testing is complete, and if the batch fails the test it must be destroyed. The state requires marijuana establishments to maintain plans “adequate to deal with recalls due to any action initiated at the request of the commissioner and any voluntary action by the producer to remove defective or potentially defective marijuana products from the market or any action undertaken to promote public health and safety by replacing existing marijuana products with improved products or packaging.”70 Marijuana cannot be packaged for sale in amounts larger than one month’s supply. The packaging must be labeled with the strain, the quantity of marijuana, information on the active ingredients, including THC, and a terpene profile (chemicals that give plants certain aromas and flavors).71 The laboratories that conduct the testing must register and be approved by the state, and must be independent from all other persons involved in the marijuana industry.72

Other states are also experimenting with good practices. New Jersey allows the state to test both marijuana plants and the soil in which they are grown.73 Delaware requires marijuana facilities to file voluntary testing plans with the state, and the state can also conduct random testing.74 Laboratories in Massachusetts do not have to register with the state, but they must be certified by a third-party that itself meets certain standards, and cannot have an owner that is also an owner of a marijuana establishment.75

Colorado has the strongest edibles regulations, which mandate that a standard serving of THC is 10 milligrams, and edibles cannot be produced with more than 100 milligrams. Any edible product with more than a single serving of THC must be “physically demarked in a way that enables a reasonable person to intuitively determine how much of the product constitutes a single serving,” and each serving must be marked with the state THC symbol to differentiate it from a regular candy or baked good.76 The packaging for edible products must display the serving size of active THC in the product, the serving of marijuana in the product, the total amount of active THC, and a warning that the effects of edible marijuana can be delayed for two or more hours.77 And when consumers take the edibles home, it must be separated into one child-resistant container per 10 milligrams of THC.78

However, good laws on the books are not always sufficient. States also need to ensure that those laws are being enforced so that tainted marijuana is not ending up in the hands of consumers and patients. Colorado provides a cautionary tale, where despite regulations banning certain pesticides, the ban was not being enforced and testing was being set aside. Governor John Hickenlooper (D) had to issue an executive order declaring the contaminated marijuana a public health hazard and directing a variety of state agencies to ensure its destruction.79

The truth is that most states fall short in this area and would benefit from the federal government being able to offer them guardrails to guide their laws. Arizona has good inventory controls, but no testing requirements.80 California has neither. Washington requires testing only for moisture and mold, not pesticides, and although it has banned certain pesticides, there are no punishments for a business who uses them anyway.81 Further highlighting the need for federal involvement, Washington’s list of banned pesticides is essentially educated guesswork that cannot be backed up by hard research until the federal government permits it. In Oregon, the state did not even consider, much less include, pesticides that kill funguses or improve the look of marijuana plants on the list of pesticides for which to screen—even though both of those types of pesticides are commonplace in the industry and can have risks to public health.82 And most states fail to require effective labeling, packaging, and dosing of edibles.

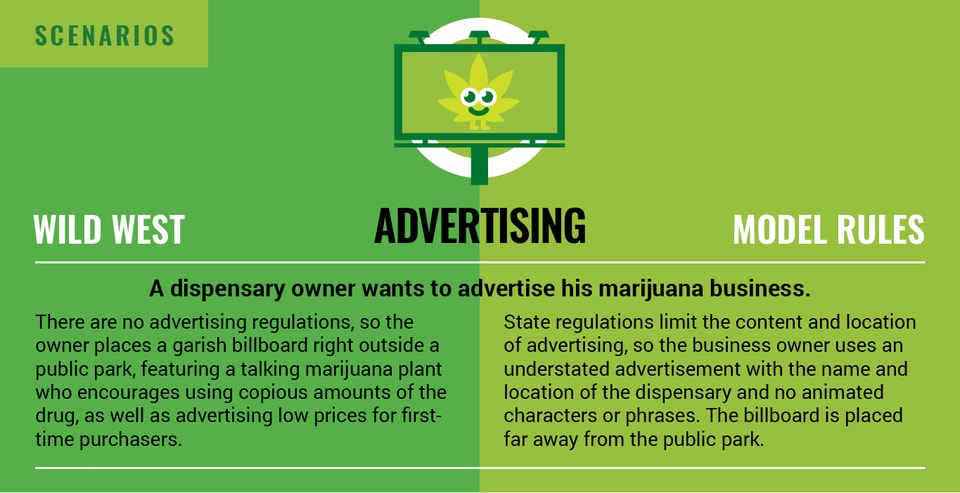

Advertising

Legalizing marijuana begs the questions of how and where it will be advertised, and in what ways those advertisements will affect vulnerable groups like children. When it comes to advertising regulations, states need to balance capitalism and the free speech rights of marijuana businesses with public health interests. In some places where marijuana is legal only for medical purposes, rather than recreational use, there have been concerns that billboards and sign twirlers target the general public rather than patients who qualify for medical marijuana.83 This is an issue of which legalization advocates should be wary, as opponents of legalization have used threats of billboards advertising marijuana-laced candy outside of churches and schools to great emotional effect to turn voters against legalization.

On this issue, like most social issues, the key to winning over Americans in the marijuana middle is to be the most reasonable person in the room. One example of doing the opposite is the glaringly tone-deaf “Buddie,” a talking marijuana bud clad in a super hero outfit that proponents of Ohio’s Issue 3 used as a mascot in their failed ballot initiative. Buddie drew complaints from both children’s advocates and many marijuana legalization advocates alike, and was compared to the infamous Joe Camel, the ubiquitous and controversial cigarette salesman.84 But while the federal government took steps to crack down on the camel, its options for taking on future reincarnations of Buddie will be limited if Congress removes marijuana from federal jurisdiction—or if it maintains the current blanket prohibition.

The Policy Solution

States should effectively regulate marijuana advertising to ensure, for example, that commercials for marijuana products don’t run during Saturday morning cartoons. One way some states have addressed this is by prohibiting physical marijuana advertising within a certain radius of churches, schools, community centers, and daycare centers. States should also require that advertising is not false or misleading, especially related to the efficacy of marijuana or any stated therapeutic effects. There should be limitations on the size or visibility of advertisements, restrictions on the use of marijuana symbols, and prohibitions on content that promotes over-consumption. Promotions like discounts for first-time buyers or prizes for purchasing marijuana should be limited as well. This is, of course, in addition to regulations prohibiting marketing aimed at minors.

The Current Landscape

Alaska is a good model for rules on marijuana advertising. Advertisements can't be within 1,000 feet of a library, park, any child-centered facility, a substance abuse or treatment facility, or on a public transit vehicle or bus shelter. Advertising can't be false or misleading, promote excessive consumption, or represent that the use of marijuana has curative or therapeutic effects. All advertising must have warnings about the health risks associated with marijuana, that marijuana is intoxicating and may be habit forming, and that marijuana is impairing and users should not operate vehicles or machinery while under its influence. Retail stores can place up to three signs on the property, but signs can't be larger than 4,800 square inches. Plans for advertising must be filed with the state as part of the license application process.85

Other states also have good policies in place. In Oregon, advertising can’t encourage excessive or rapid consumption or the use of marijuana for its intoxicating effects, nor claim that marijuana is safe.86 Colorado effectively bans television advertising before 10:00pm, and commercials cannot show people consuming marijuana or marijuana products.87 Minnesota doesn’t allow images of marijuana or colloquial references to the plant in advertising, and advertising must be pre-approved by the state.88 In Washington, marijuana establishments may not have any product giveaways, coupons, or distribute branded merchandise.89 In addition to prohibiting merchandising, Massachusetts and New Jersey don’t allow dispensaries to sell marijuana-branded merchandise. Montana, New Hampshire, and Vermont don’t allow any advertising at all.90

Despite the fact that this issue is salient and emotionally-laden for many in the marijuana middle, a number of states with legalized marijuana still have no advertising regulations at all. This list includes Arizona, California, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, New Mexico, and Rhode Island.

CONCLUSION

When it comes to marijuana policy, perhaps more than any other issue today, states are the true laboratories of democracy, and that should continue. There are potentially many different ways to design marijuana regulatory systems that effectively address these important federal concerns. But at the same time, too many states are failing to address them at all. This cries out for the federal government to establish policy guardrails to help steer state regulatory systems in the right direction. Given the current prohibition on marijuana in the Controlled Substances Act, the federal government’s hands are tied—it can only take an all or nothing approach by cracking down on legal markets completely or ignoring them all together. And should Congress pass a bill that lacks sufficient guardrails, like Senator Bernie Sanders’ (D-VT) Ending Federal Marijuana Prohibition Act, the federal government will have even less ability to intervene to protect these legitimate federal concerns. Not every state marijuana law is created equal, and the federal government should not have to treat them as though they were. The federal government has a Bureau of Alcohol and Tobacco—why should marijuana be left totally up to the whims of the states? Instead, Congress should pass legislation like Representative Suzan DelBene’s (D-WA) SMART Enforcement Act, which would maintain federal influence over these and other national concerns, while still giving responsible states a safe haven from federal prohibition.

APPENDIX

To see how each state approaches the interests discussed in this report, click here to download a survey of all 23 state regulatory systems.