Report Published June 21, 2012 · Updated June 21, 2012 · 11 minute read

Boatloads of Growth: Recapturing America’s Share of Asia-Pacific Trade

By 2020, the Asia-Pacific’s $10 trillion import market will present vast opportunities to support U.S. economic growth and wider prosperity for America’s Middle Class. But, over the past decade, the U.S. share of key Asia-Pacific markets has actually plummeted–by over 40%. Retaking America’s share of these rapidly expanding economies—beginning with trade deals like the TransPacific Partnership (TPP)—could pay huge dividends: over a half trillion dollars in additional U.S. exports, supporting millions of good American jobs.

The humble shipping container isn’t much to look at, but this ubiquitous metal box has revolutionized world trade. Since 1990, global container shipments have surged by almost 600%, lowering costs for shippers and customers worldwide.1

Containers also tell trade’s story.2 In 2008, for every five cargo containers that Asia sent to the United States, America sent back only two, resulting in gluts of empty containers at U.S. West Coast ports.3 Repositioning these unfilled containers can require sending entire boatloads of empty boxes back to Asia–floating illustrations of America’s trade deficits with countries like China and Japan.4 But, in the decade ahead, U.S. producers and workers will have growing opportunities to fill boxes bound for Asia-Pacific markets5 with more “Made in the USA” products.6

This report explains why it is vital for America to seize a greater share of growing Asia-Pacific import markets. Based on our analysis of trade data, we find that:

- While the value of U.S. exports to 12 key Asia-Pacific markets has been increasing significantly, America’s share of these markets actually fell by 43% between 2000 and 2010;

- By 2020, the annual value of goods imported by key Asia-Pacific markets will approach $10 trillion—equivalent to two-thirds of the entire American economy in 2010. This burgeoning import market will create huge new opportunities for U.S. exporters and workers; and

- Regaining America’s historical share of key Asia-Pacific markets would—in 2020 alone—increase U.S. exports by almost $600 billion, supporting over 3 million jobs.

Our report recommends that America set an explicit goal of winning back a larger share of Asia-Pacific trade. To do this, the United States must shake off old notions about trade agreements and become a “rules maker” in the Asia-Pacific, leading a long-term effort to conclude the TransPacific Partnership and a growing circle of trade deals that establish strong, modern, and comprehensive trade rules throughout the region. And we must increase enforcement of trade rules and export promotion to ensure that our exporters can benefit from our existing trade arrangements.

The prize for cracking open the Asia-Pacific market is enormous. It is vital that America get a bigger share.

Finding #1

America’s Share of Exports to Key Asia-Pacific Markets has Plummeted 43% in 10 Years.

In the past, Asia was primarily a low-cost producer of goods destined for U.S. and European consumers. But, now, Asia’s own consumers are playing a growing role in boosting global demand.7 Container traffic into China is already expanding faster than China’s outbound shipments.8 In a recent survey of over 300 global CEOs, almost half responded that Asia’s growing spending power offers the single biggest opportunity to increase their sales.9

Asia’s consumers are increasingly demanding high-quality goods and wholesome foods. They travel more and need insurance and modern financial services. Growing Asian trade and commerce is driving added business spending and investment in modern infrastructure. And, as developing Asia becomes more prosperous and urbanized, it faces demands to weave stronger social safety nets, improve living standards, and increase spending on education, health care, and the environment.10

How well positioned is America to tap into emerging Asia’s strong growth? If past is prologue, America’s track record as an exporter to the Asia-Pacific offers two seemingly contradictory answers.

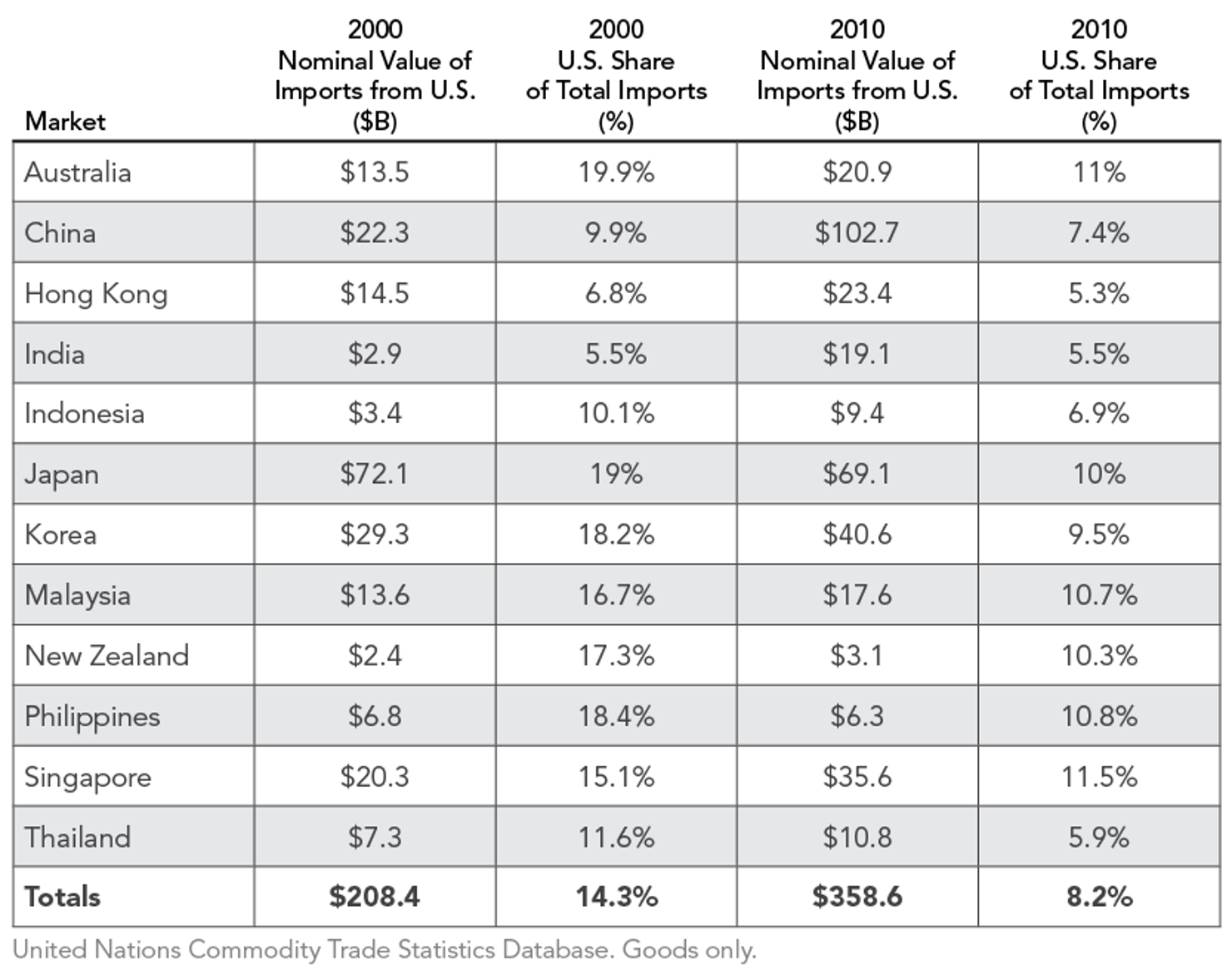

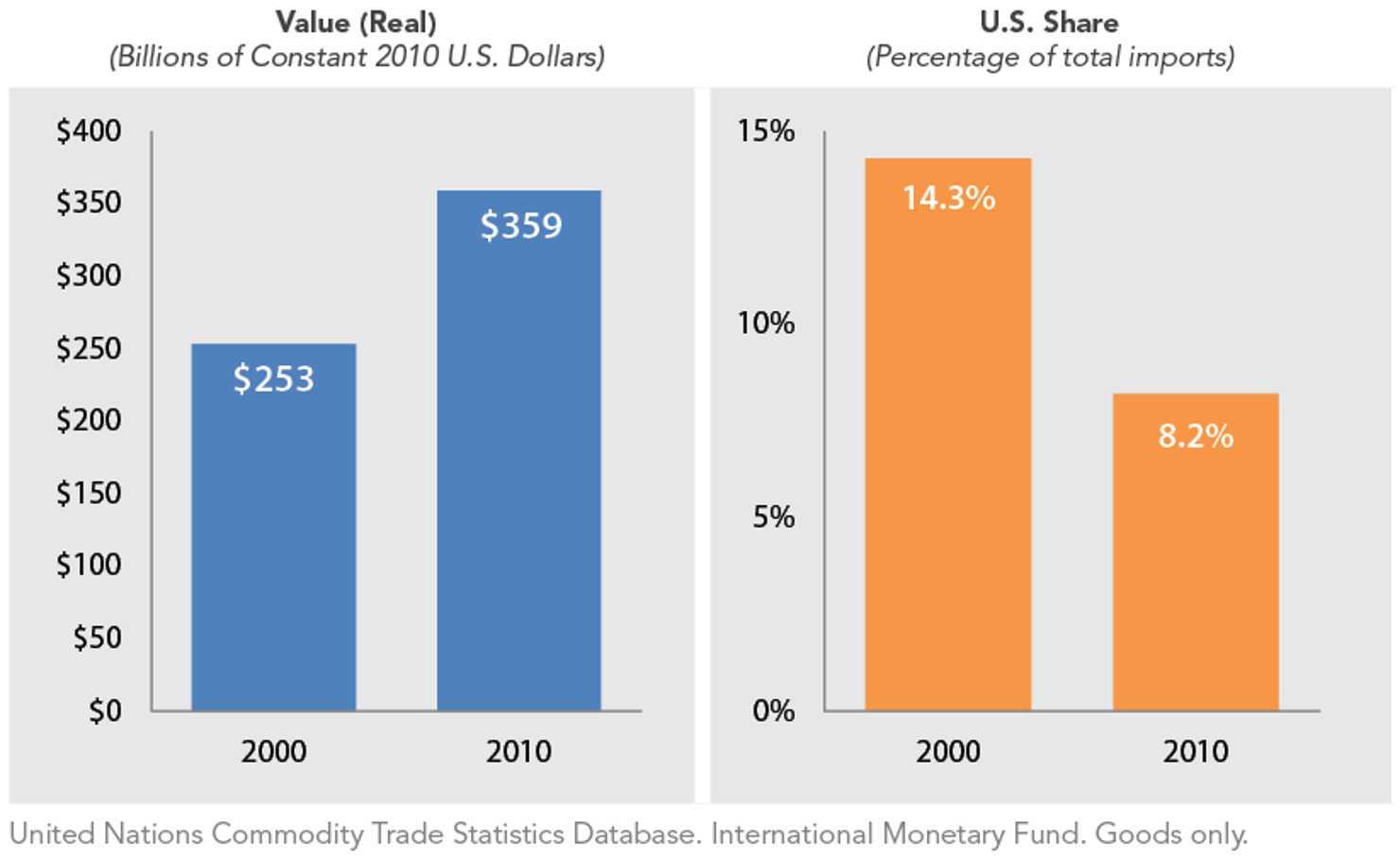

On the one hand, the value of U.S. exports to Asia has been growing substantially and is poised to continue to grow. Over the past decade, the Asia-Pacific region has been the fastest-growing destination for U.S. exports, expanding by 89% between 2001 and 2010, compared to 48% growth in U.S. exports to Europe.11 Our own analysis of UN and IMF data shows that the value of U.S. imports into 12 key Asia-Pacific markets12 rose from $208.4 billion in 2000 ($253 billion in 2010 dollars) to $358.6 billion in 2010.13

Yet, at the same time, America’s share of Asia-bound trade has been declining—in many cases quite significantly.14 According to our analysis, from 2000 to 2010, the U.S. share of total goods imports into these same 12 Asia-Pacific markets fell by 43%—from 14.3 to 8.2%—even as the value of those same imports consistently increased:

Imports from United States into Key Asia-Pacific Markets

U.S. Goods Exports to 12 Leading Asia-Pacific Economies

Why is this happening?

One of the most significant reasons for the falling U.S. market share in the Asia-Pacific is the continuing proliferation of trade deals among other countries in the region. In 2000, the Asia Pacific region had four major trade arrangements. Today, there are 39 major deals. The ASEAN countries15 now collectively have separate trade agreements with China, Japan, and Korea. The region is exploring new trade architectures, including a possible ASEAN+6 deal (ASEAN plus China, Japan, Korea, Australia, India, and New Zealand).16 And China, Japan, and South Korea have recently opened exploratory talks on a trilateral trade agreement.17

Because most of these trade arrangements exclude the United States, American exporters are increasingly on the outside looking in when it comes to new opportunities in growing Asian markets. As countries in the region continue to pursue trade deals that reduce trade barriers among themselves, their existing barriers to U.S. exports will loom even larger.18 Experts warn that regional trade arrangements that shut out the United States would significantly reduce America’s ability to tap into future Asian growth.19

America’s share of Asian markets is falling for other reasons, as well. Asia’s highly competitive producers are worthy rivals and aren’t giving up new regional opportunities and consumers without a fight.20 Other countries have also been highly aggressive in promoting their trade in the region, through means that are both legitimate (e.g., Germany) and unfair (e.g., certain Chinese practices). And, as we detailed in our July 2010 Third Way report, “Why We Need Fairer Trade: How Export Barriers Cost America Jobs,” countries throughout Asia continue to use a wide array of highly discriminatory, unfair, and illegal barriers to block American exports.21

Why is this important?

The long-term decline in the U.S. share of Asia-Pacific markets points to the risk that strong headwinds will keep U.S. exports from meeting their full potential in the region. Our exports to the region will grow, but not as robustly as they could. And that means America would get a much smaller economic boost from the vast growth in Asia-Pacific trade in the years ahead.

Finding #2

Key Asia-Pacific Markets Will Import Almost $10 Trillion in Goods in 2020.

The world’s top eight container ports are in the Asia-Pacific.22 In the coming decade, these already-busy container hubs will need to ramp up even further to serve a rapidly growing Asia.

Asia-Pacific economies have been on a growth tear for the past two decades23 and strong, continued economic growth is forecast for the region through 2020 and beyond. Six of the world’s ten fastest-growing major economies in the coming decade (including China and India) will be Asian countries. Virtually all of the Asia-Pacific region will be growing at rates much faster than the United States.24

Growing Asian demand will be propelled by a rapidly expanding flock of new middle class consumers. The Asia-Pacific middle class is expected to triple by 2020, growing from 525 million in 2009 to 1.75 billion in 2020, vaulting from less than one-third to over one-half of the world’s total.25 In turn, this swelling and increasingly urban middle class will power a huge escalation in private consumption across developing Asia, in countries including Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam. (By 2020, China’s private consumption alone is forecast to increase some ten-fold–to $10 trillion.26)

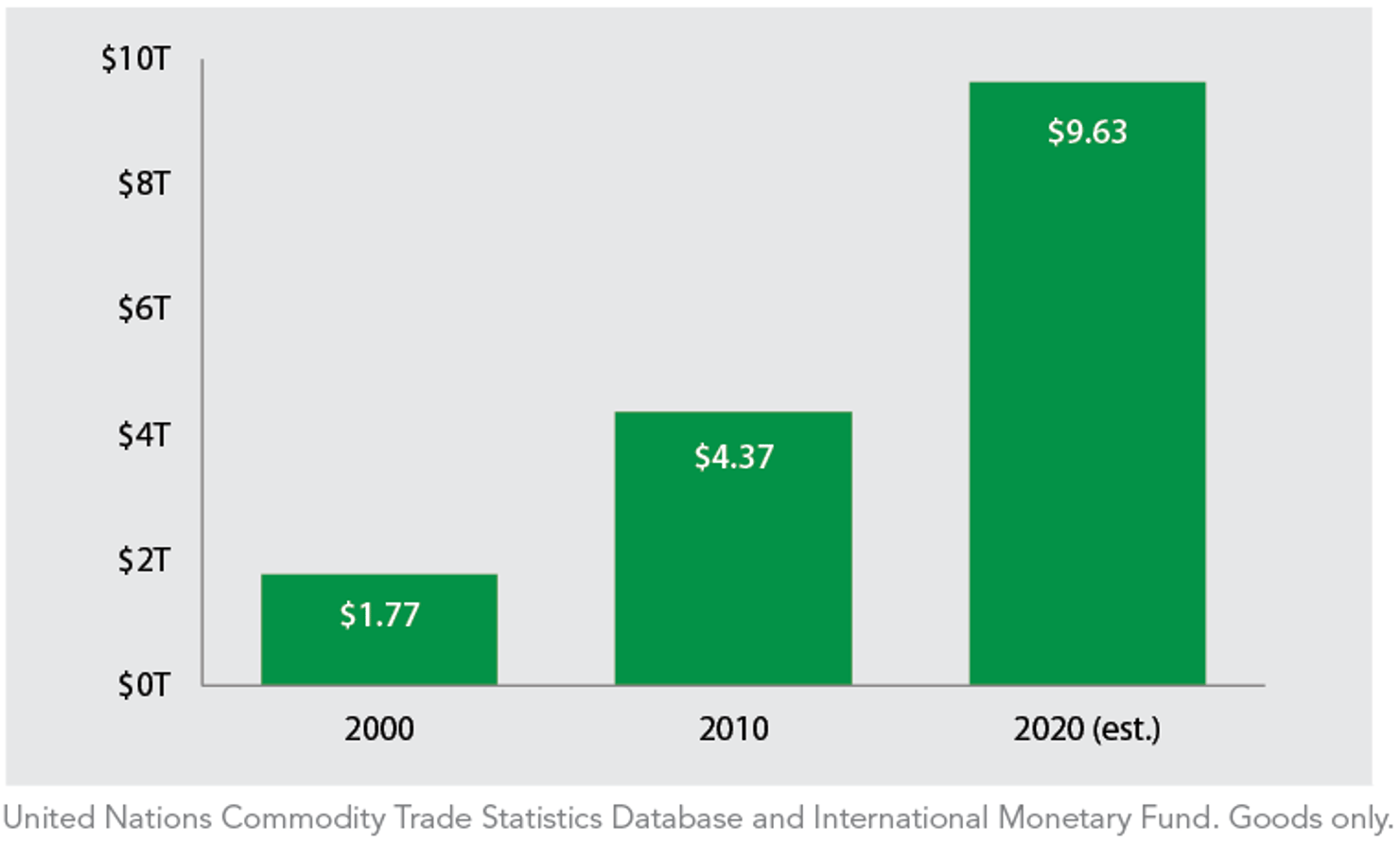

Most importantly from America’s perspective, this robust growth will power surging trade in the Asia-Pacific, creating countless opportunities for U.S. exporters.27 Third Way projects that, by 2020, annual imports of goods by 12 leading Asia-Pacific economies will surge to $9.63 trillion (in 2010 dollars), more than double their value ($4.38 trillion) in 2010.28

Total Goods Imports by 12 Leading Asia-Pacific Economies (Trillions of Constant 2010 U.S. Dollars)

To put this vast 2020 Asia-Pacific import market into perspective, an import market of $9.63 trillion (in 2010 dollars) would be two-thirds the size of the entire U.S. economy in 2010.29 And our projection does not include Asian imports of services, such as finance, logistics, entertainment, and professional services, which will account for hundreds of billions of dollars or more in additional imports in 2020.30

Finding #3

A Bigger U.S. Share of Asia-Pacific Markets Would Increase U.S. Exports in 2020 by Almost $600 Billion.

What would it mean for America if the United States could help our highly competitive exporters and workers31 grab a bigger slice of the growing Asia-Pacific economic pie?

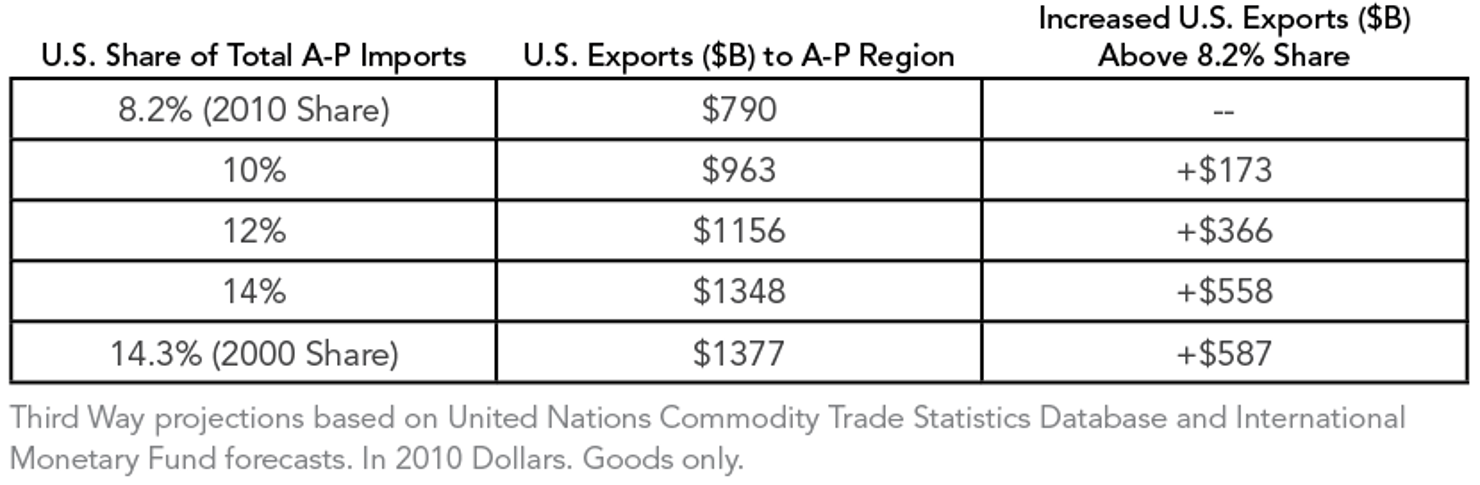

Based on our import projections for 12 key Asia-Pacific markets, in 2020 alone:

- Recapturing America’s year 2000 14.3% share of these markets would mean $1.38 trillion in U.S. goods exports to these markets, supporting over 7 million U.S. jobs; and

- A 14.3% import share would yield $587 billion more in U.S. exports and over 3 million more U.S. jobs than America’s 2010 share of 8.2%.32

To put these added exports into perspective, $587 billion in additional exports is equivalent to almost half of America’s total goods exports to the entire world in 2010.33 And these projections cover only goods. America’s highly competitive service providers could add even more exports and jobs through an increased share of Asia’s lucrative and growing market for services.34

Projected U.S. Exports from Higher U.S. Shares of 12 Key Asia-Pacific Markets (2020)

But for America’s exporters to capture a larger share of growing Asia-Pacific markets, the United States must continue to pursue a sustained, long-term effort to clear away trade barriers that keep American trade from achieving its full potential throughout the Asia-Pacific. We offer below a number of recommendations for this important effort—recommendations which we will expand upon in future reports.

Recommendations

To ensure that America’s economy benefits fully from emerging Asia’s dynamic growth, the United States should set the ambitious goal of returning the U.S. share of exports to key Asia-Pacific markets to the higher levels America enjoyed in 2000.

To do this, the United States must be an active “rules-maker” in the Asia-Pacific region. It must shake off old notions about trade agreements, conclude a strong TPP agreement, and set the ambitious goal of establishing a comprehensive, rules-based trade deal spanning the Asia-Pacific–and including India and China–within the next decade.

Trade integration in the Asia-Pacific has strong momentum; it will proceed whether America engages or not. If America does not fully engage in Asia, our exporters will lose valuable access to Asian markets. Studies project that we would lose billions of dollars in current trade and hundreds of thousands of current jobs, and we’d lose even more in future trade and jobs,35 And if we settle for being “rules-takers” and let China and others set rules, Asia’s trade template won’t include strong disciplines on issues that matter to the United States, such as IP protection, sound regulation, state-owned enterprises, and labor and environmental rules.

On the other hand, if the United States and like-minded partners can establish strong, modern, and comprehensive trade rules for the overall Asia-Pacific, America would be poised to expand its share of Asia’s vibrant growth.36

The TransPacific Partnership trade agreement would create a vital new trade architecture: an American-influenced, comprehensive, rules-based model for Asia-Pacific trade. The TPP would break down barriers on an across-the-board basis with eight countries that, together, comprise the fourth largest export market for U.S. goods and services. Perhaps even more importantly, the TPP would provide a firm foundation on which America and its partners can build a broader architecture for rules-based trade among the nations of the greater Asia-Pacific, eventually including India, Japan, China and others.37

Finally, the United States must ensure that American exporters and their workers can fully seize opportunities in Asia-Pacific markets under current trade rules. This will require:

- Ramped up trade enforcement, focusing especially on the most economically significant and pernicious trade barriers in emerging Asia;38

- Smart investments in trade resources to assure that America has enough boots on the ground to open up key Asian markets to U.S. trade;39 and

- A comprehensive initiative to promote U.S. exports to Asia that builds on the successes of the Administration’s National Export Initiative.40

Building a comprehensive, rules-based structure for Asia-Pacific trade will pose novel issues and countless challenges, both at home and abroad. It will require great patience and years of sustained effort. But, like America’s transformative work in building durable transatlantic institutions in the aftermath of World War II, a sound system of rules for Asia-Pacific trade will yield important benefits for the United States and vast opportunities for America’s Middle Class.

And it will ensure that more and more of the containers arriving at busy Asian ports are filled with “Made in the USA” products.