Report Published July 28, 2017 · 20 minute read

Guide to Section 702 Reform

Roger Huddle & Gary Ashcroft

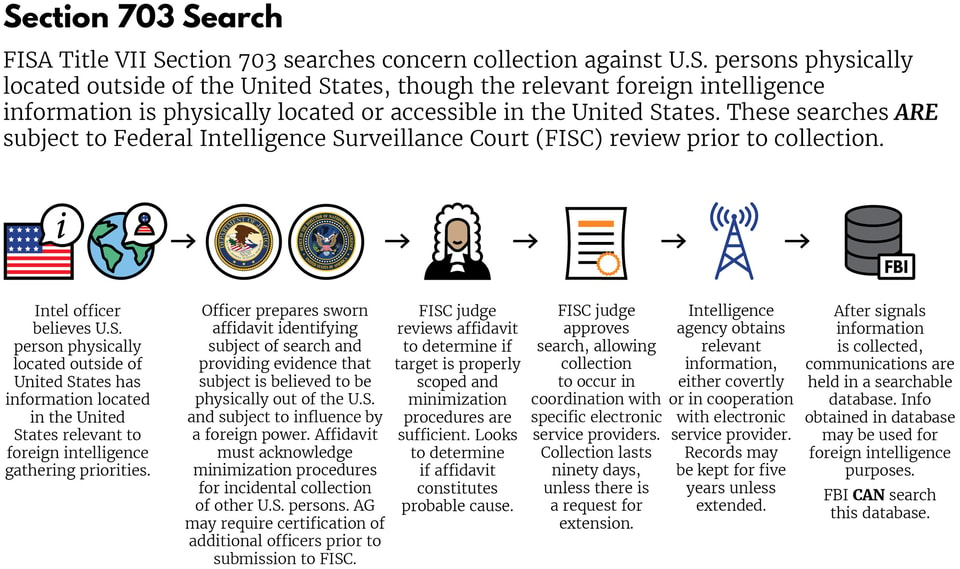

Before the end of the year, Congress must revisit the FISA Amendments Act (FAA), a law which, together with its provision known as Section 702, is one of the U.S.'s most valuable and controversial tools to combat threats to the nation. Lawmakers are considering a number of reform proposals as they decide how to reauthorize the law. While we believe it is an important tool, it has some serious flaws when it comes to Americans’ privacy. We would ask members of Congress to ensure that any reform address two problem areas in Section 702: (1) domestic law enforcement access to foreign intelligence records and (2) the international distrust of U.S. tech companies that comply with Section 702.

This paper is a primer on Section 702 and reforms for that law. Part I explains how government surveillance works generally. Part II explains Section 702 specifically. Part III details reasons to reform the law to address civil liberties and economic concerns. And Part IV examines potential reforms that have been under discussion.

What laws govern surveillance?

In confronting national security threats, the U.S. gathers information using its Intelligence Community (IC). Composed of 17 different agencies, including the National Security Agency (NSA), FBI, and CIA, the IC collects information for military operations, diplomatic purposes, and to defend the homeland against terrorism or other dangers.1

The NSA, the primary focus of Section 702, conducts electronic surveillance by collecting communications from the Internet, radio, phone calls and satellites. Founded after World War II, the NSA’s mission has evolved with changing threats and technology. During the Cold War, its primary focus was on Russia, but after 9/11 its focus shifted to terrorism.2 Just as the NSA’s focus has changed, so too have the communications technologies it surveils. These technological innovations, like the Internet, have made it harder for the NSA to track terrorists in some respects, but they have also increased the agency’s surveillance capabilities. Given such changes in threats and technologies, President Bush authorized new spying programs in the wake of the 9/11 attacks that gave the NSA access to a vast quantities of data, on the order of hundreds of millions of individual communications, both inside and outside the U.S.3

Congress initially deferred to the President on these secret NSA programs, but that changed following public and judicial scrutiny and Democrats reclaiming Congress in 2006. With the debate and passage of the FAA in 2008, Congress sought greater oversight of NSA programs to address potential abuses of American’s privacy rights.4 Public outrage over the 2013 Snowden revelations about the size, scope, and targeting of intelligence gathering conducted on domestic communications has further fueled calls for oversight and reform, with privacy advocates and technology corporations arguing that the NSA and IC violate Americans’ privacy rights.5 In contrast, the IC argues that its surveillance is lawful and essential for national security.6

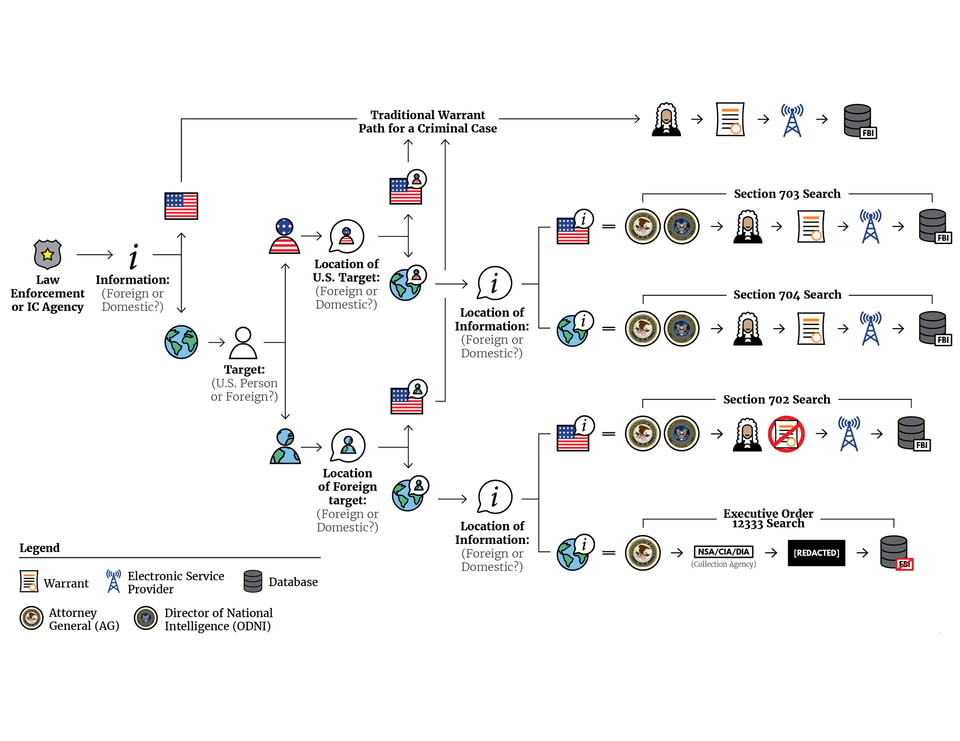

The laws governing U.S. surveillance programs vary based on the location of the targeted individual and the location of the collection. In addition, different U.S. government agencies have different rules based on whether they are focusing on domestic law enforcement – the security of Americans here at home – or foreign threats. The main classifications for U.S. surveillance programs are: (1) foreign communications; (2) domestic communications; (3) domestic communications with foreign links; and (4) foreign communications that use U.S. networks. The sections below set out the legal frameworks for each.are: (1) foreign communications; (2) domestic communications; (3) domestic communications with foreign links; and (4) foreign communications that use U.S. networks. The sections below set out the legal frameworks for each.

Foreign communications

The IC gathers information about foreign communications conducted exclusively outside of the U.S. under Executive Order 12333 (EO 12333). EO 12333 was signed by President Reagan and modified in subsequent years by other presidents.7 The order provides the NSA with broad latitude to collect communications for a variety of intelligence priorities, including traditional espionage, diplomatic negotiations, terrorism, or transnational threats.8 Because the Supreme Court has held that the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution does not usually apply to non-U.S. persons located abroad, surveillance conducted under EO 12333 does not require a warrant.9

This graphic details the process for conducting a search under EO 12333:

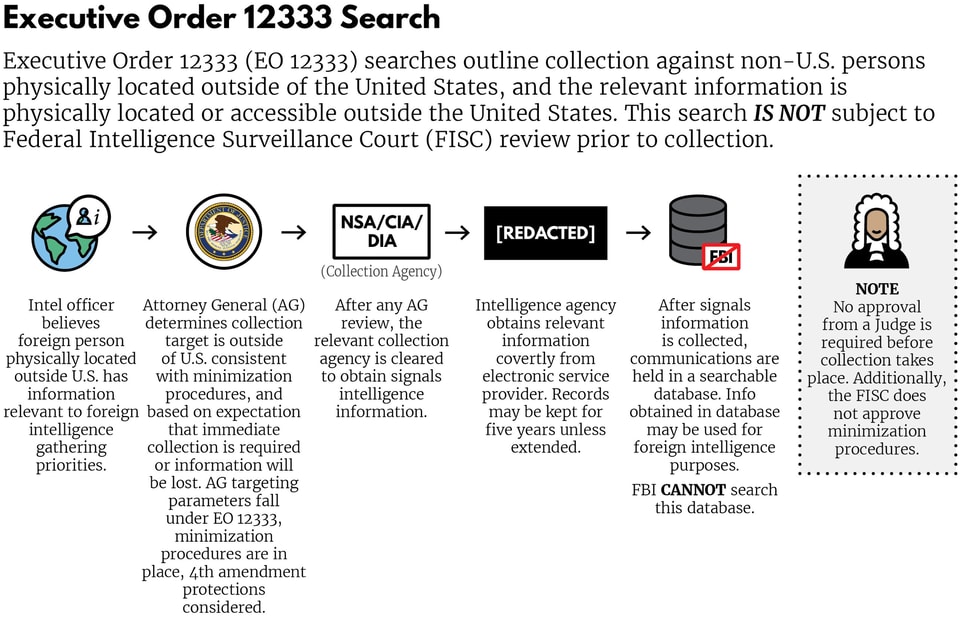

Domestic communications

Inside the United States, the Constitution is the law of the land, and the Fourth Amendment generally requires warrants for surveillance. Law enforcement officers for the FBI, DEA, or state and local police obtain warrants by convincing judges that there is probable cause that a location or a person has evidence of a crime.for the FBI, DEA, or state and local police obtain warrants by convincing judges that there is probable cause that a location or a person has evidence of a crime.10 Upon convincing a judge, requesting officers are issued a warrant, which can be used to search tangible targets, like homes and cars, or intangible targets, like stores of data or communications. Once officers obtain a warrant, they may begin surveillance. When federal agents obtain a warrant to monitor electronic communications, it is known as obtaining a Title III warrant.

This graphic details a traditional process for obtaining a search warrant:

Domestic communications with foreign links

When federal law enforcement officials conduct domestic surveillance, they usually seek a warrant from a federal judge.11 But if IC agents want to monitor someone in the U.S., or a U.S. person outside the U.S., suspected of espionage or terrorism, they seek a warrant from a different court: the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC).12 That court, created under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), issues warrants if intelligence officials can demonstrate probable cause that a person is acting as an agent of a foreign power.13 This process differs from a Title III warrant in that the IC need only show probable cause that someone is an agent of a foreign power, not probable cause for evidence of a crime.14

Congress passed FISA and created the FISC to guard against abuses of government surveillance that occurred prior to the late 1970s.15 But while FISC and FISA served that purpose well for a time, they eventually clashed with the realities of the Information Age.

Foreign communications that use U.S. networks

The Warrant Clause of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution generally applies to searches conducted within the U.S. The Warrant Clause provides citizens with rights that protect against unreasonable searches, and in practice this has required probable cause prior to any search under the Title III process outlined above. But the rise of the Internet challenged this traditional formulation, as internet communications by foreign persons located abroad often transit communications infrastructure in the United States.16 This technological change allows the NSA to collect communications inside the United States that it once had to collect abroad. So, lawmakers and intelligence officials faced the question: should these communications, made by foreigners, be granted the same constitutional protections as domestic communications?

Initially, the answer to that question was “yes.” Prior to the 9/11 attacks, if the IC wanted to search foreign communications that transited the U.S., it had to obtain a warrant from the FISC. However, this requirement became unworkable as the volume of communications grew – intelligence officials had too many requests for warrants, and the FISC faced an imposing backlog.

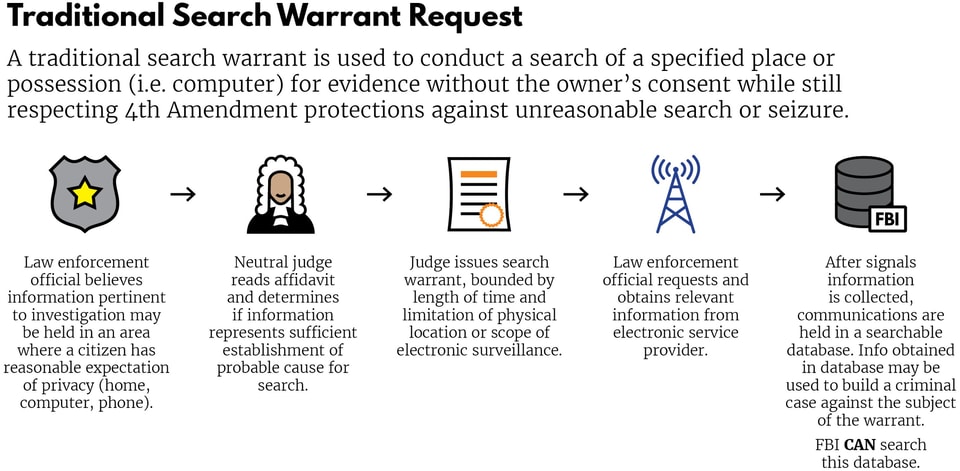

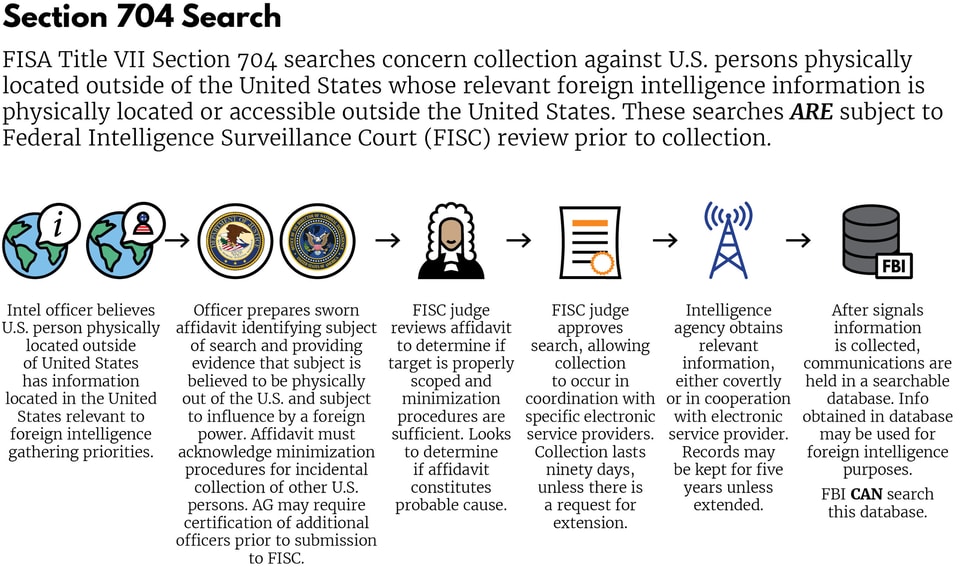

Due to the new collection opportunities created by the growing field of electronic communications and the public demand for increased intelligence to combat terrorism, then-President Bush authorized the NSA to expand its collection practices and ability to target domestic communications following the 9/11 attacks.17 This expansion came under public scrutiny following a 2005 New York Times disclosure of the programs and under Congressional scrutiny when Democrats took control of Congress following the 2006 elections.18 Such scrutiny raised questions about the legality and oversight of NSA surveillance, moving Congress to pass the Protect America Act (PAA), which gave the surveillance a blessing from Congress.19 When flaws were discovered with the PAA, Congress tweaked their authorization for the surveillance by passing the FISA Amendments Act of 2008 (FAA), commonly referred to by one of its provisions, Section 702. Though the FAA contained other provisions, including Sections 703 and 704, which covered searches specifically targeting U.S. persons, Section 702 has become the main focus of reform efforts.

This graphic details the process for conducting a search with Sections 703 and 704:

How does Section 702 work?

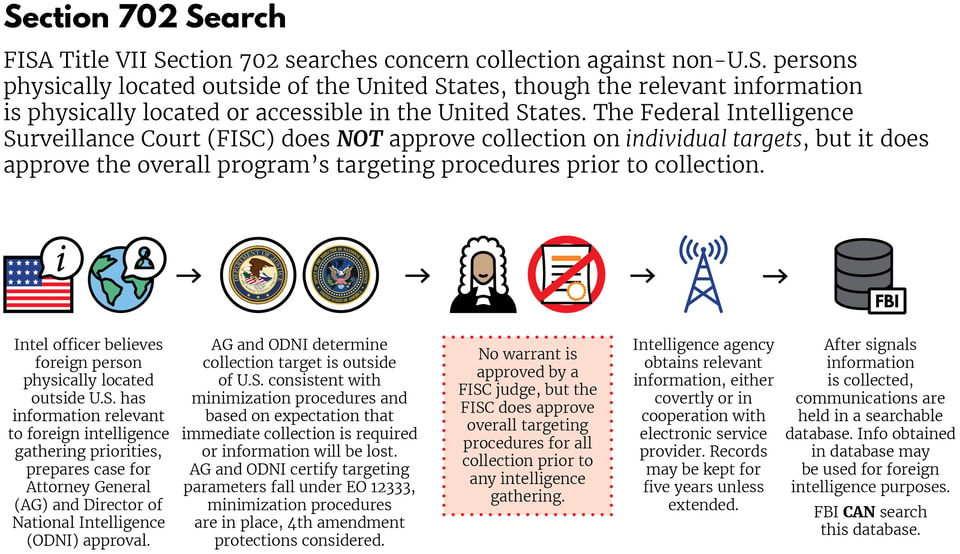

Section 702 created a new regime to oversee foreign communications that enter the U.S. Instead of requiring a warrant, as with domestic communications, or being exempt from judicial oversight, as with exclusively foreign communications, Section 702 established a hybrid system. Judges on the FISC court would oversee the broader surveillance programs, but they wouldn’t oversee specific collection requests for an individual. Instead, each year they would approve standards, submitted by the Director of National Intelligence and the Attorney General, for targeting foreigners, protecting the privacy of U.S. persons while conducting surveillance, and disposing of outdated communications gathered during surveillance.20

This graphic outlines the process for conducting a Section 702 search, highlighting its hybrid nature:

The privacy features (referred to as minimization guidelines) and targeting provisions of Section 702 are implemented primarily through two kinds of information collection, commonly known as PRISM surveillance and Upstream surveillance.21 According to the IC, these programs have proved invaluable in combatting threats to the nation. The following two sections explain how PRISM and Upstream work.

PRISM

First revealed in the Snowden leaks, PRISM is a program for collecting intelligence from U.S. companies, like Google and Facebook, which provide Internet content services, like email, VoIP calls, and social media platforms. Under PRISM, the government sends an identifier (like an email address or username) to a company. That company is then obligated to provide communications to or from that identifier to the U.S. government.22

For example, say Joe the Suspected Terrorist has an email account ([email protected]) with a hypothetical U.S. company named C-4 Communications. The NSA asks C-4 to provide the government with all communications to and from Joe’s email address. Upon receiving Joe’s communications, the NSA enters them in a database where it and other IC agencies can analyze them to see if Joe has any terrorist plots up his sleeve.

Upstream

Unlike PRISM, Upstream collection culls information directly from the “backbone” of the communications network, the physical network of cables that carries electronic communications. The government works with companies that build and maintain communications infrastructure, like Verizon or AT&T, and asks them to provide communications to or from particular email addresses, IP addresses, or phone numbers. This facet of Upstream is commonly described as “to/from” collection.23

Upstream’s “about” collection, which was recently discontinued, went beyond “to/from” to allow for collection when an identifier appeared in the content of a communication.24 This distinction can be understood by analogizing Upstream collection to a phone wiretap. If a law enforcement officer places a wiretap on someone’s phone number, she can listen to all conversations to or from that number – the equivalent of Upstream’s “to/from” collection. But say the officer could listen to any phone conversation, regardless of who it is to or from, that merely mentions a particular phone number – that would be the equivalent of “about” collection.

“About” collection’s real-world implications can be illustrated through the following example: Suppose that Gayle is a New York-based journalist investigating terrorist groups. In the course of her reporting, she discovers the email address for Joe the Terrorist, a Russian citizen in Syria. She thinks that her D.C.-based colleague, Harold, should interview Joe, so she emails him Joe’s email address. With “about” collection, even though Gayle didn’t communicate with Joe, her email to Harold could be swept up in Upstream surveillance.

As mentioned earlier, the NSA recently stopped its “about” collection, based on concerns that it lacks the technical ability to protect U.S. persons’ information in a way consistent with FISC court rulings.25 But if the NSA can resolve its technical challenges to properly safeguard U.S. person information, its leaders have raised the possibility of renewing this form of collection.26

Successes

The creation of Section 702 satisfied a pressing need– it removed the requirement to seek warrants for intercepts of foreign communications that crossed the U.S. Since its inception, Section 702 has been a valuable tool for the IC, with the NSA saying that it is “the most significant tool in [the] NSA collection arsenal for the detection, identification, and disruption of terrorist threats to the U.S. and around the world.”27 Further, the IC reports that Section 702 “contributed in some degree to the success” of 53 counterterrorism programs over its first five years.28 Independent third-parties support these claims – the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, a statutorily-mandated body reinvigorated by President Obama following the 2013 Snowden disclosures, stated in a 2014 report that “the information the [702] program collects has been valuable and effective in protecting the nation’s security and producing useful foreign intelligence.”29

The IC points to specific incidents that it claims illustrate Section 702’s value. Former FBI Deputy Director Sean Joyce cited a 702 success at a 2013 House Intelligence hearing, when he pointed to its role in uncovering a plot to bomb the New York Stock Exchange.30 In 2016, IC officials stated that Section 702 was instrumental in disrupting a plot to bomb the New York City subway.31 More recently, in 2017, Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats revealed that Section 702 enabled U.S. forces to kill ISIS’s finance minister, Haji Iman.32

But despite 702’s successes in providing intelligence to stop terrorist plots abroad, there are still serious questions about its use by law enforcement against Americans at home.

Why reform Section 702?

Though Section 702 is a valuable tool, Congress designed it with an eye toward the norms of foreign surveillance, not the constraints of the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment. This has led Section 702 to negatively impact (1) the rights and civil liberties of Americans in domestic law enforcement and (2) the international competitiveness of American businesses.

Law Enforcement Concerns

When the FISC reviews and approves Section 702 programs, it does not do so on a particularized, individual basis, as the Fourth Amendment’s Warrant Clause usually requires.33 This is normally not a problem when the government uses those programs to search for foreign threats. But sometimes a search of 702 data will yield information on an American in contact with a foreign target, a result known as incidental collection.34 For example, say Sharon, a U.S. citizen, emails Joe Foreigner outside the U.S. who, unbeknownst to her, the NSA is monitoring under Section 702. Even though Sharon’s email may have nothing to do with terrorism or foreign intelligence, when the NSA searches for Joe’s communications, her emails would be “incidentally collected” too.

Fourth Amendment

Americans’ “incidental” communications are stored in IC databases along with foreign data collected by the IC. FBI agents can, and routinely do, search these databases for information on crimes or people that may be in the U.S., using what is known as the “backdoor search” or “U.S. person search” loophole.35 And while 702 programs were created to safeguard the U.S. from foreign threats, law enforcement officers can use them, without obtaining a warrant, to gather evidence of non-national security crimes, like drug trafficking or even tax evasion.36 This effectively puts the NSA’s tools in the hands of the FBI without the full safeguards of the Fourth Amendment, creating a significant vulnerability for Americans’ privacy.

Sixth Amendment

Further, law enforcement can use information obtained through the backdoor search loophole against criminal defendants without telling them about it. This represents a potential abuse of citizens’ constitutional rights, namely the Confrontation Clause of the 6th Amendment, which requires prosecutors to reveal to defendants the sources of evidence used against them. And while FISA does require prosecutors to notify defendants when they introduce 702-derived evidence, the Justice Department issued no notices to criminal defendants during the first five years of Section 702’s existence. While prosecutors have issued notices since then, they have been rare – the ACLU reports that as few as ten have been issued.37 Without notice, a defendant has no chance to challenge the Constitutionality of using an intelligence database, without a warrant, to convict someone in the U.S.

Congressional Attention

Congress has repeatedly expressed concerns about the backdoor search loophole. While the original FISA created a “wall” that limited foreign intelligence sharing between the NSA and the FBI, post-9/11 changes to the statute removed that “wall,” allowing not only for intelligence sharing, but also the use of that intelligence for domestic law enforcement. Congress’s passage of Section 702 in 2008 did not fix this issue and in fact helped exacerbate it. However, starting in 2012, several members of the House and Senate began to express concerns about backdoor searches. This has resulted in a number of bills designed to close the loophole, as well as the introduction of the USA Freedom Act in 2014, which was designed to reign in the IC’s domestic spying power.38 Despite these efforts, the loophole remains open and, indeed, grew larger when, in 2015, the FBI changed its procedures for protecting the privacy of U.S. persons caught up in incidental collection.39

Economic Concerns

The 2013 Snowden revelations highlighted how U.S. technology firms worked with the NSA to collect Section 702 surveillance. This disclosure caused some overseas customers to grow wary of dealing with U.S. companies, with this adversely impacting U.S. competitiveness. For example, in 2014, Germany refused to renew a contract with Verizon to provide Internet services, citing concerns about surveillance.40 Earlier, in 2013, Microsoft lost a contract to provide email services to the Brazilian government over 702-related issues.41 Norwegian company Runbox, a Gmail competitor, experienced a 34% increase in customers in 2013-2014, likely due to surveillance anxieties.42 Some analysts believe that fallout from Section 702 could cost American cloud computing companies hundreds of billions in revenue.

Section 702 also threatens key international agreements that undergird American firms’ overseas operations. The EU-U.S. Privacy Shield is an agreement that allows U.S. firms to transfer data to and from Europe, provided they comply with EU guidelines.43 Now, Privacy Shield is under attack in EU courts, with litigants arguing that U.S. surveillance, including Section 702 collection, violates EU law.44 Although some may dismiss these suits as minor annoyances, they shouldn’t. After all, the European Court of Justice struck down the previous incarnation of Privacy Shield, the EU-U.S. Safe Harbour Agreement, due to concerns about U.S. surveillance.45

If Privacy Shield is struck down, the ramifications could be disastrous for U.S. tech companies. Many companies’ business models depend on the free flow of data to and from Europe. Privacy Shield’s downfall could impede that flow by requiring companies to build expensive data centers in Europe.46 While the construction of data centers would hurt the finances of tech giants like Google and Facebook, a requirement to build them could make it even more difficult for emerging American companies to grow internationally.

702 Reforms

Section 702 has been a valuable tool to combat threats to America. But a useful tool can always be improved and made safer. The evidence is clear that Section 702 has troublesome impacts on both the privacy of U.S. persons and U.S. economic interests. Before Congress renews it, it should reform the law to address such concerns.

One reform, commonly known as “closing the backdoor search loophole,” would require FBI personnel to seek a warrant before searching 702 databases for the content of a U.S. person’s communications. A number of bills have sought to implement this reform, including Representatives Thomas Massie (R-KY) and Zoe Lofgren’s (D-CA) “Massie-Lofgren Amendment,” which they introduced in 2014, 2015, and 2016.47 Although never signed into law, the House passed Massie-Lofgren by substantial margins in 2014 and 2015, signaling that there is broad-ranging support for such legislation.48 Passing a measure like Massie-Lofgren would help put Section 702 in line with 4th Amendment privacy protections.

Congress could also reform Section 702 to impose “use restrictions” on U.S. person information. IC members, when searching 702 databases for foreign intelligence, may inadvertently turn up U.S. person information. Implementing “use restrictions” on this information would mean that, while it could be used for national security or counterintelligence purposes, it could not be used for a criminal investigation of a U.S. person by the FBI without first obtaining a warrant.49

Other potential reforms could codify current IC policies. For example, the NSA recently announced that it was ending its collection of “about” communications under Upstream.50 But this decision was only a policy change, and the NSA could resume “about” collection in the future. To guard against this, Congress may consider Representatives Tulsi Gabbard, Scott Perry, and Jared Polis’s “Preventing Unconstitutional Collection Act,” a 2017 bill currently under consideration that would codify the prohibition on “about” collection. Passing this bill, or one like it, would guard against the NSA resuming “about” collection of U.S. persons’ information without public debate and statutory changes.

Another reform could address notice requirements. Currently, the Justice Department does not disclose its standard for determining whether a criminal defendant should receive notice of Section 702-derived evidence.51 Some privacy advocates believe this secrecy is designed to hide prosecutors’ use of a narrow definition of “Section 702-derived” that allows them to skirt notice requirements.52 Codifying a broad definition for “Section 702-derived” would ensure that defendants are properly notified about the sources of the evidence used against them.

Congress can also clarify the ways that the IC can access Upstream data. The Snowden leaks revealed that the Special Source Operations division of the NSA, which is responsible for collecting communications from telecom companies, “[does] not typically have direct access to the systems” of those companies.53 The key word here is “typically,” which seems to imply that there are some cases where the NSA can collect data directly from telecoms’ networks. This is worrisome, as requiring the NSA to go through companies to access their data provides those companies with additional opportunities to challenge potentially unlawful information requests before the FISC. Congress could resolve ambiguity about this, and empower companies to protect their customers’ data, by mandating that the NSA always go through companies when gathering new information from their systems.

Finally, because the government gains so much information from U.S. companies under Section 702, working with and through those companies should be the only way for the IC to collect intelligence from them. This change would ensure that the government does not try to gather American companies’ data through surreptitious, clandestine means.54 Instead, the IC would only use Section 702’s process, and other court-supervised intelligence procedures, to gather data. By enacting such a mandate, Congress would give American companies a leg-up on their foreign competitors, as they would benefit from greater privacy protections than companies based overseas and subject to foreign intelligence agencies.

Conclusion

Section 702 is a critical tool to combat threats to the nation, but its value should not make U.S. overlook the serious and sustained problems it poses for Americans’ civil liberties and the interests of American companies at home and abroad. As Congress considers the Section 702 program, it must address these issues to ensure the long term health of this intelligence capability and codify the Judicial and Congressional oversight needed to guard against potential abuses. The problems in Section 702 collection necessitate a fulsome debate about the role, scope, targeting, and oversight of the program. Our suggested reforms are merely one facet of this broader debate, but take these problems head on. Whether lawmakers decide to enact reforms like requiring a warrant before viewing an American citizen’s communications or requiring disclosures of notice requirements, they can rebalance security interests with those of privacy and business in future intelligence gathering. As they do, they can ensure that Section 702 will continue to defend our nation from foreign threats, while also protecting its core values of privacy, liberty, and free enterprise.