Report Published June 20, 2011 · Updated June 20, 2011 · 12 minute read

National Security Interrogations: Myth v. Reality

Steven Kleinman

Takeaways

In this report veteran military interrogator Steven Kleinman explains:

- What interrogation actually is (and why fictional portrayals muddy the waters);

- How coercive practices actually undermine interrogators’ long-term goals; and

- Why experienced interrogators know that rapport-building is the most effective means to extract valuable information from detainees.

Following the U.S. raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan, several Bush officials claimed that so-called "enhanced" (i.e. coercive) interrogation techniques performed on a few high-value detainees generated actionable intelligence used to locate and ultimately kill the al Qaeda chief.1 While Obama Administration officials have refuted this claim, questions remain regarding the effectiveness of coercive techniques. Unfortunately, constructive dialogue is hindered by a general misunderstanding of the interrogation process—reinforced by inaccurate Hollywood depictions—and a lack of comprehensive analysis of intelligence acquired through coercive versus non-coercive means.

Unfortunately, the ubiquitous media portrayals of brutal interrogations as an effective model for eliciting information have often proven more influential in informing the decisions of policymakers, and public opinion, than have science or actual experience. While heavy-handed methods may have some measure of appeal as entertainment, evidence-based research in interrogation strongly suggests that the stress of coercive interrogations is more likely to cloud memory than to clarify it. Similarly, coercion is likely to also generate false information and obfuscation as the detainee struggles to meet the demands of his interrogator. On the other hand, if an interrogator focuses on building a useful degree of accord with the detainee, the questioner has a much better chance of collecting useable data.

Clearly, a more realistic appraisal of interrogation’s true capabilities and limitations is necessary to avoid wasting this precious national security tool in the crises of the future.

Defining Interrogations and the Rapport-Based Approach

To understand how this media-driven image falls short, it is important to understand the overall purpose of an interrogation. An interrogation is the systematic questioning of an individual who is reasonably and objectively assumed to possess information of potential intelligence and/or law enforcement value.2 The interrogator’s central challenges in such a process are:

- Eliciting a sufficient level of cooperation from the detainee so his or her knowledge may be explored;

- Gaining this cooperation in a manner that does not undermine his or her ability to reliably recall events, places and personalities; and

- Asking questions that increase the potential for gaining accurate details and decrease the possibility of obtaining false, misleading, or distorted information or details, inducing corrupted recall.

The competitive exchange of information between the interrogator and the detainee can be categorized into two primary categories:

- Information the detainee may provide to the interrogator: This includes not only information of intelligence value, but also information that provides insights into the detainee’s interests and motivations.

- Information the interrogator may provide to the detainee: This might include the current realities outside the detention environment, or timelines for release.

The interrogator must deftly manage this complex, information-driven dynamic by continually evaluating, monitoring, and synthesizing the detainee’s needs, hopes, fears, and interests to create an environment that encourages cooperation. By doing so, the interrogator builds the critical rapport with the detainee. Once this is established, it is possible to create a situation in which the detainee realistically perceives that providing accurate and comprehensive information is in his best interests.3 At that point, information is much easier to elicit. Additionally, this approach has often induced detainees to volunteer important operational information that the interrogator may not have suspected they possessed.4

Cooperation as the Interrogator’s End Goal

The primary purpose of national security interrogations is to gain actionable information, and experienced interrogators know the best way to accomplish this goal is to use a rapport-based approach. Interrogators who employ coercive measures are seldom successful, and use of such methods often reflects inexperience or impatience. A more sophisticated, relationship-based strategy is consistently the best means of generating accurate information. Simply put, overt aggression may serve short-term emotional interests, but will have long-term negative repercussions. As the former head of the vaunted East German foreign intelligence service once observed, “interrogations… should serve to extract useful information from the prisoner…not to exact revenge by means of intimidation or torture."5

To this effect, a detainee’s cooperation can seldom be gained, much less sustained, with coercive practices. If the U.S. requires timely and accurate information, it is preparation, patience, guile, and attention to detail that can be relied upon to generate results. Even Americans subjected to brutality in wartime interrogations are uncomfortably aware that they might have been more cooperative with their captors under other circumstances. As Jack Fellowes, who shared a cell with John McCain during their time as POWs during the Vietnam War, once noted, “The tougher [the Vietnamese interrogators] got on us, the tougher we got back at them…[although] I often thought, if they started treated [sic] us kindly, what would we do? I really think they would have gotten more information."6

Of course, questioning a detainee over a period of time is seldom a linear, concrete, and predictable process, especially when it involves high-value targets with considerable life experience and advanced education. In these situations, interrogators should be prepared to interview a detainee over a long period of time, striving to establish a bond amidst an environment shaped by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.

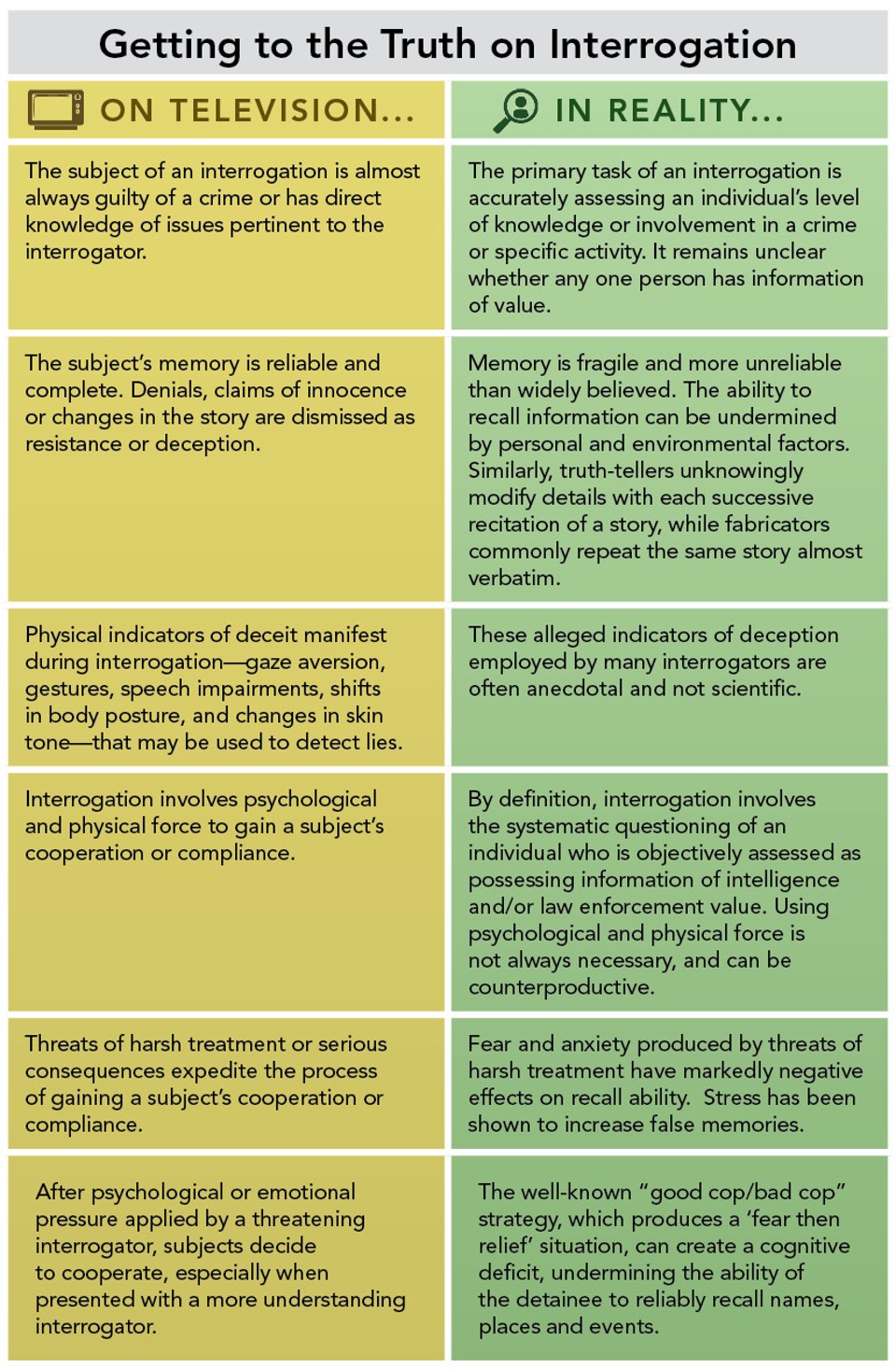

Getting to the Truth on Interrogation

To better understand the complexities and challenges of interrogations as they unfold under real-world conditions, it might be helpful to contrast the fundamental principles and processes with the fictional portrayals found on television and in books and movies. It will be readily evident that reality is far more complicated than media images of snappy repartee by sharp-witted interrogators, quick capitulations from confused suspects, and a quick resolution that offers answers to every critical question.

Why Force is Ineffective

Some incorrectly assume that physical coercion is an integral part of the interrogation process.7 In fact, many have accepted the unfounded premise that the employment of physical, psychological, or emotional pressure is necessary to gather critical intelligence in the course of an interrogation.8 Further, there has been wide acceptance of the erroneous belief that vital information cannot be obtained from a resistant subject after they are provided legal protection, or treated in a manner consistent with the Geneva Conventions. This assumption is exacerbated by the equally invalid proposition that most, if not all, detainees captured under hostile circumstances possess valuable information or are able to recall information in remarkable and accurate detail.

Operational realities tell a different story. For example, the American experience in Afghanistan and Iraq revealed many detainees were misidentified as terrorists or insurgents.9 Not surprisingly, a large number of these individuals possessed little information of value, thus wasting U.S. interrogators’ time and energy. In fact, one US Army investigation conducted in 2004 in Iraq estimated that 85-90% of detainees in one major detention facility “were of no intelligence value."10 Complicating these issues was the fact that some military units employed a haphazard methodology in detaining individuals across their areas of operation, leading to “…an increased drain on scarce interrogator and linguist resources to sort out the valuable detainees from innocents who should have been released soon after capture, and ultimately, to less actionable intelligence."11

Successful interrogators understand that there are two general reasons why forcible techniques invariably generate poor results.

First, the focused application of sufficient psychological and physical force may often cause a detainee to respond to questions even if he or she has no useable information. A detainee placed under prolonged physical duress may be compelled to answer any question, even if he or she has no meaningful or relevant answer. When coercion is employed in association with leading questions—a common tactic used in coercive models of interrogation—the detainee may characteristically begin answering questions in the manner clearly suggested by the person employing the physical pressure. The detainee in such a scenario will understandably say and do practically anything to escape the torment. This force-outcome dynamic may be accurately described as compliance, as opposed to cooperation.

Of course, if the intended outcome is for the detainee to make statements regardless of his or her veracity, then coercion may be a useful tool. For example, obtaining a prisoner’s compliance for propaganda purposes was the primary focus of the Chinese and North Vietnamese interrogation programs during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, respectively. As a prisoner of war, Senator John McCain was brutalized by his Vietnamese interrogators into writing several bogus "confessions."12 One of his statements, for example, included naming the Green Bay Packers' offensive line as part of his air squadron.13

Coercion is indeed an effective means of gaining compliance—but it is a poor mechanism for acquiring reliable intelligence. In his book An Ethics of Interrogation, U.S. Naval Academy Professor Michael Skerker notes:

For a practice meant to reveal truth, interrogatory torture generates ambiguity in series. It will usually be unclear to interrogators if a given detainee has security-sensitive information; unclear if torture has compelled the truth from him; unclear whether he would have spoken without torture (interrogators who claim to have exhausted noncoercive means may simply be unskilled in those methods); and unclear if further torture would reveal more information.14

Second, interrogation is an intelligence collection initiative, not one that seeks intimidation or punishment as a fundamental outcome. Just as signals intelligence (SIGINT) captures electronic signals, and imagery intelligence (IMINT) collects photographic and digital representations of selected sites, interrogation seeks accurate, comprehensive, and unbiased information about people, places, and plans from within a detainee’s memory. A major challenge—one that an ill-trained interrogator may overlook to his or her detriment—is that human memories may be unreliable and oftentimes malleable. Human memory may be shaped or corrupted even under the most benign and non-threatening circumstances.15

Hence, it stands to reason that coercive measures can easily compromise a detainee’s constructive recall ability. Studies on this topic have demonstrated how personal and environmental stressors may diminish the ability of any individual to accurately recall detailed information.16

In an operational context, a detainee who has been subjected to sleep deprivation, overt threats, dietary manipulation, and extended interrogations is unlikely to be able to reliably and fully report information even if he or she had a desire to cooperate. Supporting this notion, Trinity College (Dublin) research psychologist Shane O’Mara offers an important observation on the effects of coercive interrogation on memory and its unreliability:

"Information retrieved from memory though the employment of coercive interrogation methods is assumed to be reliable and veridical, as suspects will be motivated to end the interrogation by revealing information from long-term memory. No supporting data for this model are provided by the U.S. Government memos describing enhanced interrogation techniques; in fact, the model is unsupported by scientific evidence."17

The Way Ahead

The Obama Administration has made a good-faith attempt to bring standards to American interrogation practices by issuing an Executive Order that extended the relevant U.S. Army Field Manual’s directives to all government-wide interrogation efforts. Nonetheless, to meet the extensive collection needs of U.S. security requirements in a legal, ethical, and operationally effective manner, the military and Intelligence Community should develop a new interrogation doctrine in order to prepare for the national security crises of the future.18 This model of interrogation should feature the following critical elements:

- A government-wide recognition that interrogation’s complex challenges are on par with those of clandestine collection operations.

- An appreciation that methods will be consistent with long-standing U.S. legal and ethical traditions.

- The long-term examination of selected high-value detainees will take place under strict standards and subject to appropriate Congressional oversight.

- Experimental research will be followed by carefully controlled trials in an operational setting to demonstrate the efficacy of emerging strategies and methods.

- Formal vetting programs will limit recruitment to a select cadre of interrogators who can effectively grapple with the complexities and ambiguities of interrogation.

- Rigorous training and standards will improve the overall level of professionalism in the interrogation discipline.

This new interrogation model must also be supported by a robust and ongoing research effort. Both basic and applied research will be necessary to develop an appropriate body of scientific knowledge. The following are recommended critical building blocks for a successful research program:

Determine how people make decisions. During an interrogation, the interrogator and the detainee are continually making decisions, forming assessments, selecting among options, and choosing to hide/reveal emotions, while simultaneously trying to shape the decision-making of the other. Thus, it is important that a successful program capture the practical applications of the best research available about how people make decisions in order to refine the interrogator’s knowledge.

Improve and augment the resilience of memory. The key to interrogation is gaining virtual access to the detainee's memory. Interrogators sometimes erroneously assume that people are able to fully and accurately recall even distant events regardless of conditions. The challenge, then, is to facilitate high-quality "recall," sometimes from individuals who initially may choose to not even answer a question.

Improve cultural literacy, especially with foreign detainees. Successful interrogators should be consistently informed by a deep understanding of the complex cultural factors that divide peoples across faiths, viewpoints, and cultures. At a minimum, the interrogation strategies should be customized for their appropriateness and effectiveness within various target populations.

Conclusion

History provides ample warning that some interrogators will be tempted to resort to physical force in the quest for information. Given the evolving threats facing Americans at home and abroad—and the relentless pressure placed upon interrogators to extract time-sensitive information from incarcerated high-value targets—this unsavory prospect will continue. The professional cadre of interrogators supporting America’s national security interests, and representing the nation’s values, must not be seduced by the siren call of coercion; rather, it must rely on a rapport-based, field-tested, scientifically-valid strategic architecture to elicit cooperation and, as a result, provide meaningful information to the country’s political and military leaders.19