Report Published April 29, 2014 · Updated April 29, 2014 · 30 minute read

Teaching: The Next Generation

Tamara Hiler & Lanae Erickson

Takeaways

This report proposes 5 big policy shifts at the national level to modernize the teaching profession:

- Creating a national standard for teaching practice;

- Refusing to subsidize teacher prep programs whose graduates don’t make the grade;

- Providing immediate student loan relief to teachers;

- Paying and promoting teachers like professionals; and

- Transitioning teachers to a modern, portable retirement system.

When you have a job opening, are you satisfied with choosing among the bottom one-third of the class? What if you have 3 million job openings?

Over the next ten years, the United States will hire approximately 3 million new teachers to enter its classrooms. This new corps of teachers will serve as the single biggest in-school determinant of whether or not our students are college–and workforce–ready for decades to come. But if past is prologue, most of these 3 million new teachers will come from the bottom third of their class, as most talented Millennials do not view teaching as a viable career option. Now is the time to modernize the teaching profession to ensure that it is seen by new workers as a prestigious career opportunity. In this paper, we diagnose the hurdles keeping the teaching profession in the past and offer a series of recommendations to attract smart, ambitious, career-oriented Millennials into the profession.

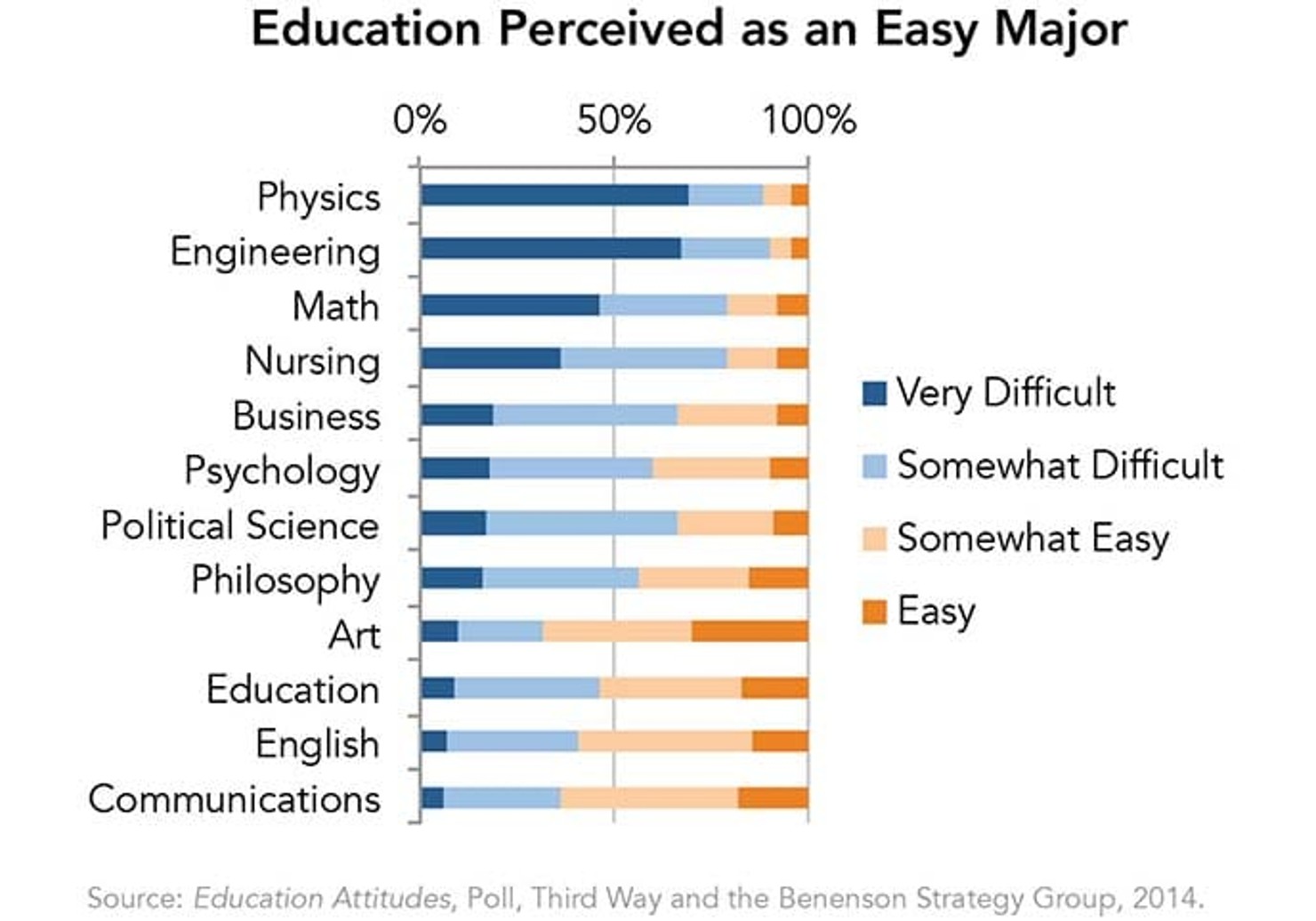

A new Third Way poll of high-achieving undergraduate students paints a fairly dismal picture of how our next generation of workers perceives the teaching profession:

- Fully half of these students believe that the teaching profession has gotten less prestigious in the last few years.

- They consistently ranked education as one of the easiest majors, with only 9% viewing it as "very difficult."

- Only 35% described teachers as "smart."

- Education was seen as the top profession that "average" people choose.

Times have changed—and so must the outdated policies we use to attract, train, promote, and compensate our teachers. Now is the time to transform the teaching profession so that the 3 million new teachers entering our classrooms in the decade to come are the best we’ve ever had.

How Did We Get Here?

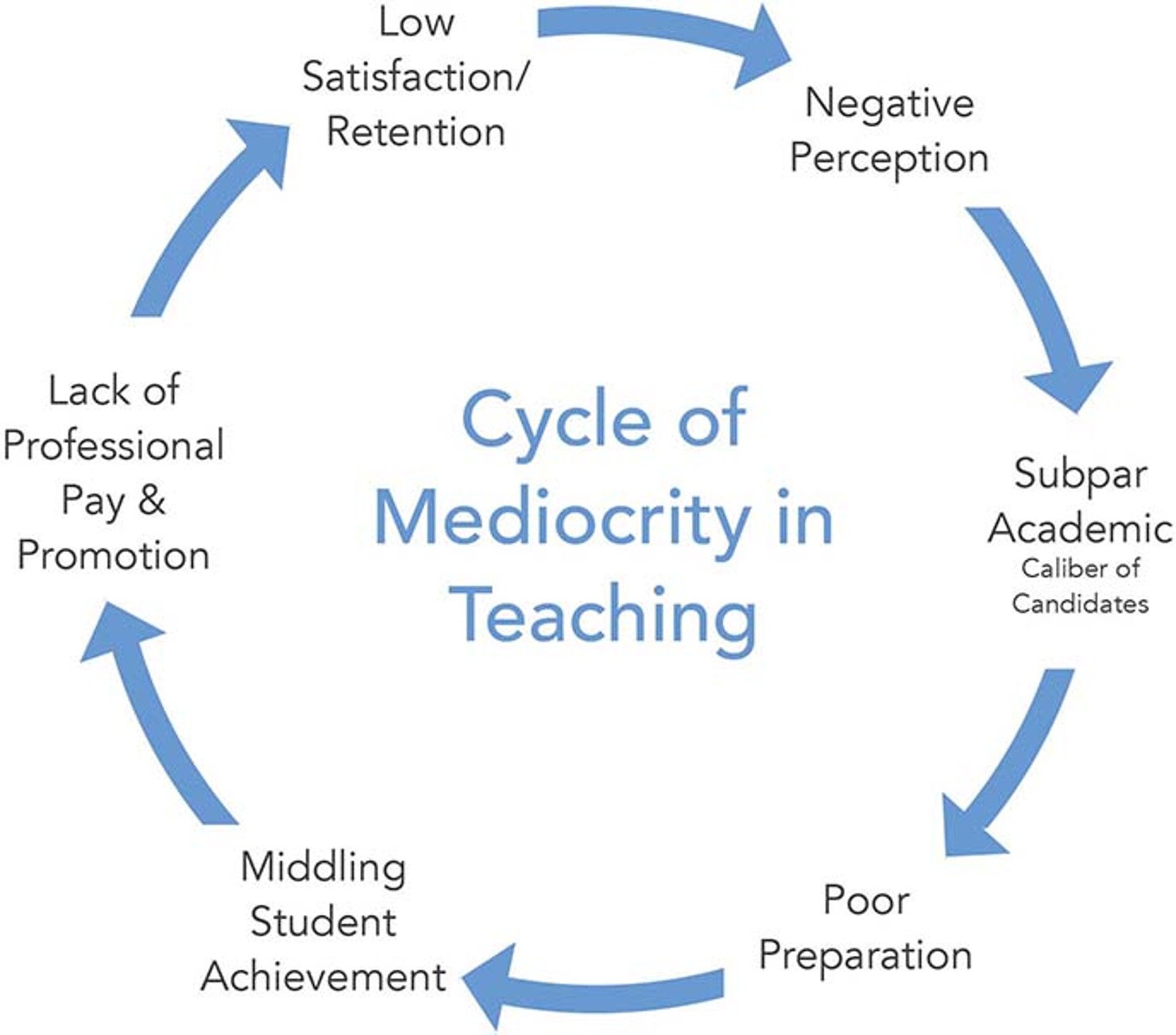

An Unsustainable Cycle of Mediocrity

Why has teaching failed to evolve into a 21st century profession—one that fosters innovation, offers a competitive salary, and provides an infrastructure for dynamic growth opportunities? The same preparation, pay structures, and retirement systems set up forty years ago are still largely intact today, forcing high-achieving Millennials to fit into a system that no longer meets their professional needs and desires. While other sectors, such as nursing, law, and medicine, have embraced major changes over the years to overhaul the way they train, promote, and compensate their employees, the teaching profession has failed to conduct a similar internal review or make the resulting course correction. This resistance to modernization dissuades high-achieving Millennials from entering the profession and pushes excellent teachers out, creating an unsustainable cycle of mediocrity in a profession that requires nothing but the best.

Teaching: Where Average People Go

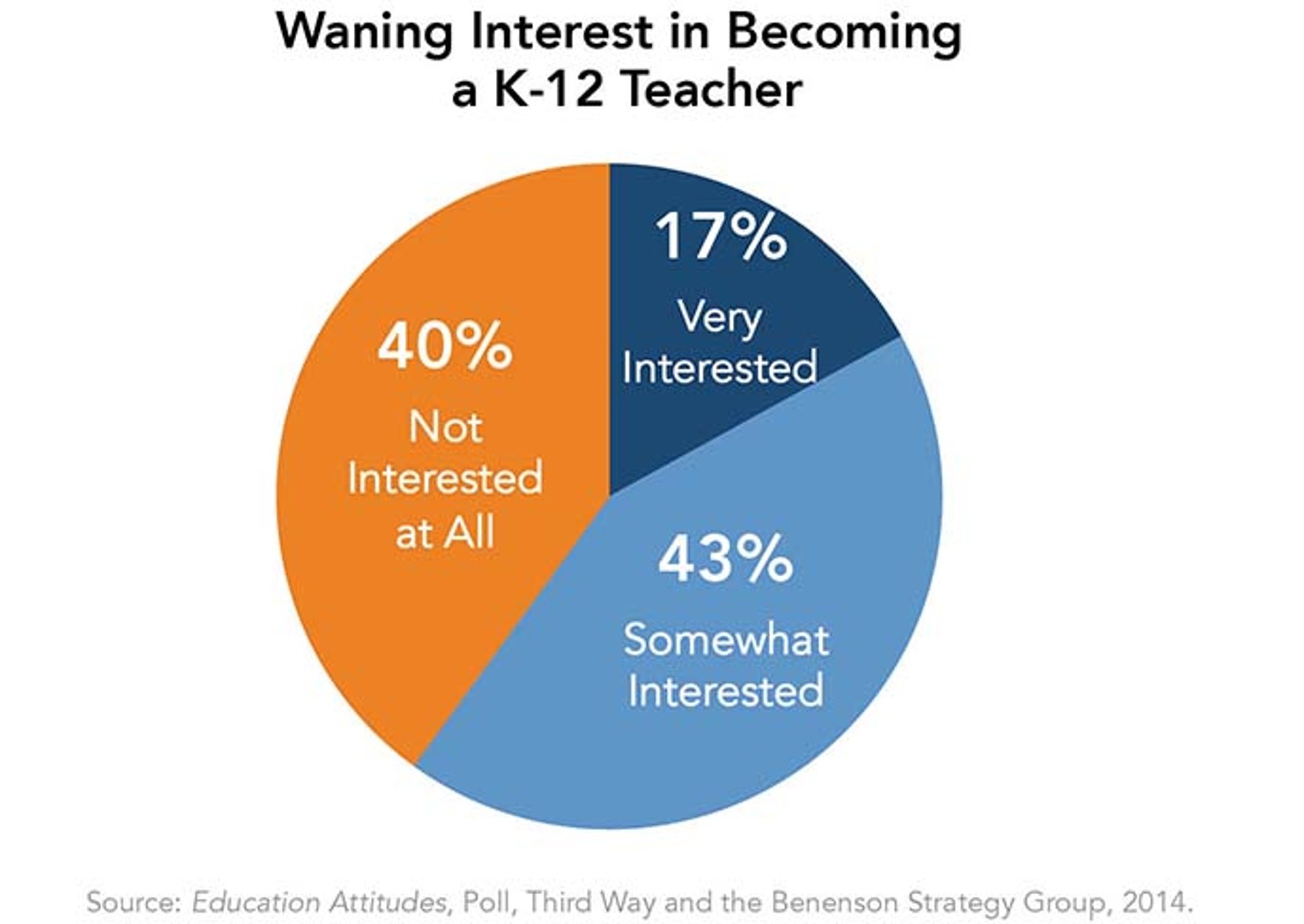

Based on the results of our poll, teaching is not seen as an ambitious or fulfilling career by most Millennials. Only 17% of high-achieving undergraduates said they would be very interested in pursuing K-12 teaching, an unsurprising number considering that 50% believe that the teaching profession has gotten less prestigious in the last few years. Compounding the problem, education as a major was viewed as one of the least difficult, on par with art, English, and communication studies, and words such as "nice" and "patient" were used to describe teachers, instead of "smart" and "entrepreneurial" like those in other more prestigious professions. In fact, education was listed as the top profession that students think "average" people go into—a scathing indictment of those we trust to educate our children.

The teaching profession has a major image problem, and piecemeal tinkering to the system cannot undo outdated policies that have brought us to this point. Although the last decade of reforms made strides in ushering in a new era of teacher accountability, these have done comparatively little to improve teacher professionalization. All too often, the conversation centered primarily on getting rid of the bad teachers, further perpetuating a negative image of the profession.

Unfortunately, this perception of mediocrity has negatively affected the national reputation of teaching, initiating a cycle of undesirable outcomes that can be felt throughout the profession. While we certainly want people who exhibit the qualities of patience and kindness to continue entering the classroom, Americans want teachers to both drive academic achievement and serve as compassionate caretakers. We need to make significant changes to the profession to ensure we can attract new recruits who can achieve both of those goals—because "average" isn’t going to cut it.

A Low Bar for Preparation & Certification

It is clear that the middling perception of the teaching profession has had a direct impact on the ability to attract and recruit high quality candidates. Today, the majority of prospective teachers in the U.S. come from the bottom two-thirds of their college classes, with nearly half coming from the bottom third.1 In high-poverty schools, this number is even more dismal, with only 14% of new teachers graduating from the top third of their class.2 This inability to attract the best and brightest puts us at a distinct disadvantage with our high-ranking global competitors, who recruit top third candidates to fill every single classroom.3 In fact, the standards for admission in most traditional programs in the U.S. are so low that two-thirds of programs accept more than half of their applicants, and a stunning one-quarter accept nearly every single person who applies.4 And the arbitrary evaluation system that allows states to self-report on the efficacy of these programs does almost nothing to provide insight into how successful these programs are at actually preparing students to succeed in the classroom. In 2011, only 24 programs in the entire country were designated by various states as at-risk (1.4% of all programs), yet just a year later, a survey by the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) found that less than half of new teachers described their training as very good, with 1 in 3 feeling unprepared for the first day of school.5

But this is not the only lamentably low hurdle in teachers’ pre-service training, as teachers must also pass a state certification or licensure exam in order to meet the standards laid out in No Child Left Behind (NCLB). In contrast to other careers that require licensure, like law or medicine, the current system for teacher certification is ambiguous and incoherent, and in most places it sets an incredibly low bar. There is no real standardization of the credentialing process across states, leaving teachers to experience varying timelines and degrees of rigor depending on where they live. Each state has the ability to create their own licensure exams, but even states that choose to use the same tests often set varying cut scores.6 And frequently, the cut scores are set so low (typically below the 16th percentile) that virtually all candidates pass, particularly when given unlimited attempts to do so.7

Efforts were made in the late 1980’s to ameliorate this issue and raise the standards of teaching across the states through the creation of the National Board of Professional Teaching Standards. Their certification process was modeled after the medical profession to create a national gold standard in teaching, and recent studies have shown that it works: teachers who are board certified consistently outperform their peers on student achievement benchmarks.8 Yet, only 3% of today’s teachers are board certified, and of those who choose to undertake this process, only 40% are able to pass their boards on the first try.9 This low passage rate stands in stark contrast to the almost 90% of doctors who are able to become board certified on their first attempt and is a direct indictment of the substandard preparation teachers receive during their initial training and subsequent professional development.10 And the number is particularly telling considering the small proportion of teachers who even attempt the boards are a self-selecting, and likely higher-achieving, group than the average teacher. Even the major teachers’ unions agree that we should raise the bar. As a recent report from the National Education Association (NEA) says, "The first step in transforming our profession is to strengthen and maintain strong and uniform standards for preparation and admission."11

Middling Student Achievement

With research consistently showing that teachers are the most important in-school factor leading to student success, it is unsurprising to see that a low bar for entry into the profession has stymied our ability to improve student learning over the last forty years.12 According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), U.S. students have experienced minimal gains in math and reading over the last decade, and despite some gains among minority students, the achievement gap still persists.13 This stagnation has also played out on the international stage, where students from 18 countries outranked those from the United States in math, reading comprehension, and science on the latest iteration of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) exam. Our scores consistently put us in the middle of the international pack, near countries like Lithuania.14

But despite efforts to address this lack of progress through increased education spending and a litany of education reforms, policymakers at the district, state, and federal levels have yet to find the right formula to increase student success across the board. Total per pupil expenditures have more than doubled in the U.S. since the 1970’s, and the U.S. spends 38% more than the OECD average for every student on elementary and secondary education.15 Efforts to improve curriculum, education standards, and teacher evaluation over the last few decades have made some strides forward for our students, but they have still fallen short. In large part, this is because our core education problem is a human capital one. We need a refocused effort on recruiting and retaining the next generation of excellent teachers to make our education system globally competitive again.

Pay & Promotion that Fails to Meet 21st Century Needs

Our ability to recruit, prepare, and retain high-quality public school teachers hinges upon our capacity to update the policies that continue to blindly view teachers as interchangeable "widgets." According to The Widget Effect, a seminal report by The New Teacher Project (TNTP), in 2009, 99% of teachers received a rating of satisfactory on their annual review.16 This blatant disregard for teacher quality finally exposed the public to a staggering reality that teachers already knew to be true—that almost all teachers are treated as equals, regardless of aptitude, effort, and success. While this system may have met the needs of previous generations of workers, Millennials are no longer wooed by a profession that willingly turns a blind eye to performance and treats all employees as indistinguishable cogs in a machine.

The infrastructure for advancement in teaching is not set up for a modern economy. The opportunities to move up the career ladder in the teaching profession are limited, at best. The overwhelming majority of teachers who stay in the profession either plateau by remaining in the classroom at the same level for years with the same responsibilities, or they choose to leave the classroom altogether to become a principal or other administrator in order to gain leadership opportunities or a raise. As a result, many of our best teachers exit the classroom, robbing our students of effective teaching. Those who stay feel their input is ignored, as a new Gallup poll demonstrated when it found that teachers were least likely of any profession to say that their opinions actually mattered at work.17 But even where classroom-based leadership platforms have been implemented, promotions are often quality-blind, sidelining excellent teachers with lower seniority for those who have been there the longest. While other 21st century professionals enjoy the freedom to grow within their careers at a pace based on their abilities and performance, teachers are still expected to "wait their turn" for meaningful advancement opportunities.

The same can also be said to describe how teachers are paid. Today, over 89% of U.S. school districts use a "step-and-ladder" compensation structure, which offers higher pay to teachers solely for their years of service and number of higher education and professional development credits—both proven to be poor proxies for classroom effectiveness.18 Instead these structures lock teachers into a restrictive system that values time, rather than quality, and fails to recognize innovation, excellence, or efficacy. Despite calls from the teachers’ unions that "the single salary schedule is the most transparent and equitable system for compensating teachers," a higher number of school districts and charter management organizations are increasingly looking to use new compensation structures that recognize and reward excellence.19 But until these systems become the norm and not the exception, high-achieving Millennials will continue to seek employment in sectors that acknowledge and incentivize talent and hard work.

High Mobility In and Out of an Immobile System

Like any other profession, teaching is not immune to the new realities of a highly mobile workforce. Only one-third of undergraduates polled believe they will stay in their first job for ten years or more, and an astounding 43% intend to leave their first job in less than five years. Although Millennials no longer see themselves doing the same thing for 30 years, the teaching profession has failed to revise a bulk of its policies to accommodate this newfound way of life. This lack of adaptation to the expectations of a new workforce is exacerbating an already high attrition rate, creating a "revolving-door" effect where over half of current teachers leave the classroom within the first five years.20 For the first time since the 1960’s, teachers with 10 or fewer years’ experience now constitute a majority of the teaching force.21

It is evident that this young and highly mobile workforce is finding teaching as a career to be increasingly at odds with their professional needs. This problem is particularly acute when examining the outdated licensing and retirement systems in which most teachers participate. Because of the incongruous process for licensing and certification, teachers who move to another state must jump through unnecessary hoops in order to transfer their credentials—or worse, start from scratch in certain cases. Outdated pension systems make this situation worse: a majority of states require teachers to pay into defined benefit pension plans, which often have vesting periods of five or ten years and back-loaded benefits for those who stay in teaching long-term.22 Those who choose to leave the profession or simply move to another state prior to vesting often end up losing what they’ve earned in the system. A recent study by Bellwether Education Partners estimates that only 44.5% of new teachers will stay around long enough to earn a minimum pension, greatly jeopardizing the retirement security of over half of the teaching workforce.23 But even for teachers who do stay, defined benefit pension plans can no longer offer the promise of the past, due to the looming threat of underfunded liabilities in most states. In fact, many states have made their vesting periods longer in recent years to compensate for their financial troubles.

The effect of a perception of teachers as "average," coupled with poor preparation, as well as outdated career ladder, compensation, and retirement structures, all feed into the reality that the teaching profession is not currently equipped to attract high-achieving Millennials. Without a major shock to the system, this cycle of mediocrity will continue to negatively impact the teaching profession, and ultimately our students, for years to come.

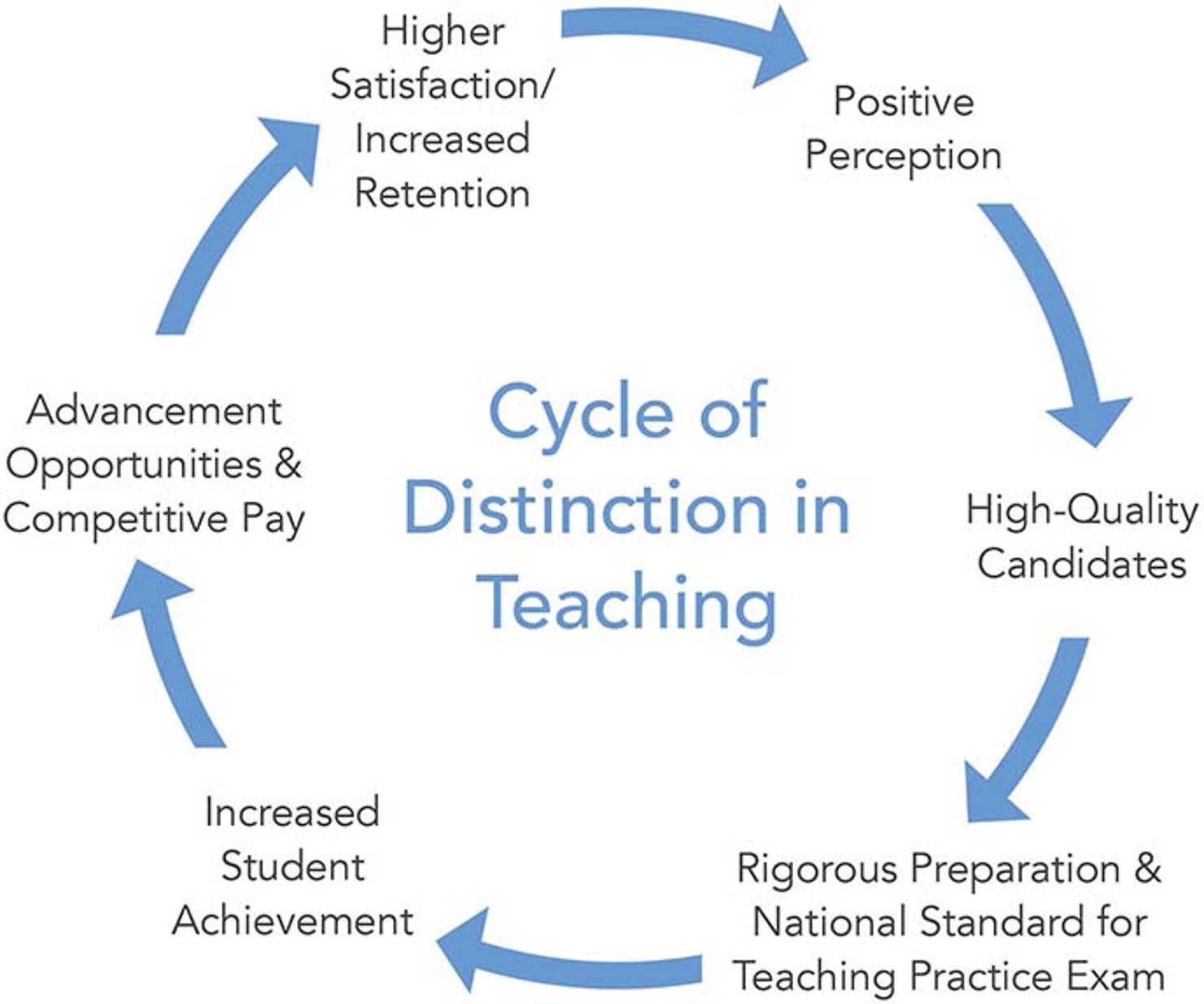

Breaking the Cycle

The good news is that this cycle can be broken. Even though few high-achieving undergraduates in our poll initially expressed interest in becoming a K-12 teacher, a quarter of these same Millennials also indicated that certain systemic reforms to the profession could change their minds. Specifically, when asked which education reforms would make them much more likely to consider teaching, "paying all teachers more,""paying high performing teachers more," "encouraging more effective school leadership," and "offering student loan repayment to teachers" ranked as the top answers. A clear set of policy changes could be enacted right now to address these issues, and other barriers keeping teaching locked into the past, to change the perception of the profession and draw the talented students we’ll need in the future.

A New Vision: "The Interrupters"

1. Create a National Standard for Teaching Practice.

The teacher certification process in the United States is an unwieldy mess, with different tests, regulatory bodies, and processes found across every state. The standards to receive licensure vary widely, with some states requiring teacher candidates to demonstrate content and pedagogical mastery and others requiring little more than passing a series of middle-school level exams. While these divergent systems may have been sufficient in the past, in 21st century America there is no reason that a teacher in Michigan should be held to a grossly different standard of entry into the profession than a teacher from Massachusetts.

New Proposal: To alleviate this problem, we must develop a national standard for teaching practice that provides a clear, linear path into the profession and sets a high bar for every single teacher, regardless of where they live. In order to teach in any American school, a teacher candidate should first pass a comprehensive test of content knowledge and pedagogical theory, as well as demonstrate teaching performance in a "stand and deliver" format. Tests like the new edTPA show promise in this area by aligning state and national standards to a multi-measure assessment and requiring teachers to actually demonstrate knowledge and content skills in real classrooms—not simply pass a test of theory.24 But while programs in 34 states are experimenting with using edTPA, currently only seven states actually have policies in place that require a state-approved performance assessment of any kind as a prerequisite for receiving licensure.25

Those who pass this exam of national stature could have a teaching credential that is portable, allowing them to apply for jobs in any state in the nation. The cut score for this exam would need to be set to where we want our teachers to be, not simply low enough for the majority of current applicants to pass, as has been and continues to be the case with new licensure assessments.26 By setting the bar high early on, and adopting effective practices similar to those used in the national board certification process, we can ensure that the teachers who have access to our students are highly qualified to teach 21st century skills from day one.

2. Stop Subsidizing Teacher Preparation Programs whose Applicants Don’t Pass the Test.

Each year, the federal government blindly pours billions of dollars, mainly in the form of student financial aid, into teacher prep programs without requiring any sort of real accountability in return.27 And if independent reviews such as the annual report by the National Council for Teacher Quality (NCTQ) are any indication, neither taxpayers nor teachers are getting an adequate return on their investment. Last year, for example, only four programs out of 1,130 reviewed received an overall rating of 4 out of 4 stars, and 1 in 7 received less than 1 star.28 Yet in 2011, only 11 states reported having low-performing or at-risk teacher prep programs, constituting less than 2% of all programs in the country.29 In fact, 35 states have never identified a teacher preparation program as low-performing or at-risk, despite being encouraged to do so under the Higher Education Act.30 Previous attempts by the federal government to raise standards and increase transparency have often ended with teacher prep programs identifying ways to game the system and continue to inadequately self-police. With each school setting its own standards of accountability and doing little to track its graduates, it is nearly impossible to know which schools are adequately preparing teachers to succeed in today’s classrooms—and which are simply wasting the money of both taxpayers and teachers.

New Proposal: The creation of a national standard for teaching practice exam would allow teacher preparation programs to be held to an equal and rigorous benchmark for the first time. If more than 25% of a prep program’s graduates fail this exam on the first try for three years in a row, that program could be deemed no longer eligible for federal money, including student loans for new incoming students. Passage rates for each teacher prep program could be publicly posted on a single website, increasing transparency that would allow aspiring teachers to select the programs most likely to set them up for success. With the implementation of new evaluation systems, teachers are increasingly being measured by whether or not their students are learning, and it is time for teacher prep programs to be held to the same standard. If not, the American people, and our teachers, have a right to take their hard-earned money elsewhere.

3. Provide Immediate Student Loan Relief to Teachers.

One way the federal government attempts to attract and retain teachers is to appropriate over a half a billion dollars each year on a patchwork of student loan assistance programs. The problem is that a majority of these programs, such as Federal Stafford & Perkins Loan Forgiveness, TEACH Grants, and Public Service Loan Forgiveness, are largely unknown to prospective and current teachers alike, and they all require teachers to wait four to ten years before reaping the benefits (or in the case of TEACH Grants, require you to pay back your funding in full with interest if you leave the profession early).31 Currently, 42% of the teaching force has less than ten years of experience and over half of all teachers leave the profession before making it to their fifth year.32 As a result, the current menu of student loan and grant programs provided by the federal government is essentially moot to a large proportion of the teaching force.

But new teachers literally cannot afford to wait. According to a recent report by the New America Foundation, the debt for new teachers has increased by 66% in the last decade. Today, the average teacher with a master’s of education degree graduates with more than $50,000 in debt, nearly $8,000 more than their MBA counterparts.33 With high mobility in and out of the profession and high loan payments facing most teachers immediately when they enter the classroom, the assistance programs available today offer very little incentive for those looking to join or remain in the teaching force.

New Proposal: Instead, a new consolidated loan repayment program that immediately assists teachers with their monthly payments could address the real needs of today’s teachers. As soon as a candidate passes the national standard for teaching practice exam, the federal government could begin making the monthly federal student loan payments for any teacher with full-time employment in a public school. After three years, these payments could continue for any teacher who is able to demonstrate that his or her students are achieving at least average growth in the classroom. By offering immediate relief, this program would serve as a much bigger value add to any young person who is considering entering the profession and a greater enticement to a new teacher who is debating whether to stay. Such a program would cost the federal government approximately $1.5 billion at the start, less than what the government already spends on teacher-related programs each year.34 The prospect of having a $500 student loan payment disappear each month is a much more alluring prospect than asking a teacher on a meager salary to hold out for possible loan forgiveness years down the line.

4. Promote and Pay Teachers Like Professionals.

In our current system, the overwhelming majority of school districts use salary and promotion structures that ignore a teacher’s effectiveness and provide little opportunity for growth. And as evident in our poll of high-achieving undergraduates, these structures conflict directly with the values young people take into account when selecting a job. When asked explicitly, high-achieving undergraduates ranked "opportunities to advance" and "salary for those established in the career" as two of the four most important factors taken into consideration when thinking about future employment (the other two were "job stability" and "current availability of jobs"). Right now, most teachers who want to stay in the profession are faced with two options: either remain in the classroom for the duration of their career with little room to take on new responsibilities or challenges, or leave to become a principal or other administrator. For most Millennials, this zero-sum career ladder holds little appeal and directly conflicts with their perception of what a career should be. The belief that workers will be rewarded for excellence with additional responsibilities and commensurate pay is a basic tenet in other professions, and it is preposterous to think that teachers don’t expect and deserve the same.

New Proposal: While the Department of Education has had some success in enticing states to begin the implementation of 21st century career ladder and compensation structures through programs like Race to the Top and the Teacher Incentive Fund, the majority of teachers still find themselves placed in school districts that value time spent teaching over quality of teaching. The federal government should direct its resources to ensure that all districts create and implement stratified career ladders and differentiated pay structures that offer the best teachers the opportunity to stay in the classroom while taking on additional responsibility and earning increased autonomy. While updating NCLB to mandate this improvement is the most permanent and direct way to ensure these changes, current teachers should not have to wait for the political uncertainty of reauthorization. Until then, all NCLB waivers granted by the Department of Education should be contingent on states requiring districts to implement modern career and compensation ladders in a timely manner.

Similar to a proposal crafted by teachers in the Department of Education’s RESPECT project last year, teachers could advance through a series of built-in career stages, such as, "beginning teacher," "professional teacher," and "master teacher."35 Teachers at the master level would take on advanced responsibilities, such as mentoring new teachers, developing curriculum, and leading professional development—all while remaining in the classroom and in front of kids. Each one of these promotions would need to be offered to teachers based on their effectiveness in the classroom, not their seniority, and would come with additional compensation. And while districts could have some latitude in how they craft their teaching career and compensation ladders, those systems would need to contain at least three levels of advancement and would no longer be allowed to promote, pay, or lay off teachers simply based on seniority.

5. Transition the Teaching Force to a Portable, Modern Retirement System.

The majority of teachers are required through their states to participate in defined benefit pension plans, which promise participants a guaranteed monthly benefit at retirement, often defined through a formula that takes years of service and highest annual salary into account. And while historically one of the rewards for choosing a career in teaching has been the promise of such a generous defined benefit pension upon retirement, recent economic instability affecting state budgets and unrealistic assumptions about market returns have caused these pensions to no longer be the sustainable guarantee of the past. As of 2012, teacher pensions in 48 states and the District of Columbia reported underfunded liabilities,creating an increasing financial burden for both teachers and taxpayers alike.36 In addition, defined benefit systems are set up to offer the greatest rewards only to those who stay in the system for 30 or more years, an increasingly unlikely path for those entering the teaching profession today. With states intentionally raising vesting periods and pinching payment formulas in order to escape financial trouble, it is estimated that only 19.7% of beginning teachers will stay long enough to qualify for a full pension benefit.37 As a result, tens of thousands of young and mobile teachers are forfeiting higher salaries up front in exchange for paying into retirement systems from which they will never reap the benefits.

New Proposal: Rather than waiting for the system to implode upon itself to create a secure retirement system for the majority of new teachers, the federal government could provide immediate assistance to states looking to engage in serious pension reform. As an incentive for modernizing outdated defined benefit retirement systems, the federal government could offer a competitive grant program to assist any state that transitions incoming teachers to modern, portable cash-balance plans during a certain time period. Structured in a similar way to the Race to the Top initiative, these federal funds could motivate states to make the politically difficult but financially necessary changes required to modernize their teacher pension systems while providing the financial assistance they need to ensure that teachers in the current system maintain the benefits they have earned.

Unlike defined benefit plans, these new cash-balance plans would allow incoming teachers to have their own individual retirement accounts (similar to a 401k), but without taking on the risk of managing their own investment. Instead, new teachers would be guaranteed a fixed-rate investment return on their employer and employee contributions each year, protecting them from unexpected market fluctuations.38 Such plans provide a promising compromise between traditional defined benefit and defined contribution plans, and they contain a number of advantages for 21st century teachers.39 For example, cash-balance plans are portable, allowing teachers who move or exit the profession to take their retirement with them (both their own contributions and the employer contributions they have earned); they accrue at a regular rate rather than back-loading benefits, escaping the undesirable incentives caused by current complex benefit formulas; and they would give districts and states the flexibility to free up money for increased salaries. Finally, the transition to cash-balance plans for new teachers would not destabilize the current system—instead providing security to those already in the profession. Current teachers could continue in their defined benefit pension plan or potentially even have the option to transfer over if they so choose, while all incoming teachers would need to be enrolled into this new modern plan in order to access the competitive federal grant funds.

A Cycle of Distinction

Each one of these policy proposals is designed to interrupt the cycle of mediocrity and transform teaching into a modern profession. The implementation of each of these changes would create a new cycle—one of distinction—allowing teachers to earn the respect and prestige that they rightfully deserve.

A Tale of Two Teachers

Under the Status Quo:Jenny has taught 3rd grade in Pennsylvania | With Proposed Changes:Sarah just began her third year as a 5th grade teacher in Pennsylvania. Next year, she will be moving back to California to be closer to her famil |

Her pathway through teaching:

| Her pathway through teaching:

|

Conclusion

In the thirteen years since Congress passed No Child Left Behind, the education system in our country has changed dramatically. The children who started kindergarten that year will graduate from high school this spring, meaning that these students—and their teachers—have lived through an era of unprecedented accountability in education, most notably the development and implementation of teacher evaluations that help identify the good teachers from the bad. But while these reform efforts have helped districts and states gain a clearer picture of the effectiveness of the teaching force for the first time, they have not yet spurred the changes necessary to attract the next generation of high achievers who might consider entering the teaching force.

As policymakers look to what should be done in our education system in the post-Obama era, the conversation must shift towards policies that will address the pervasive issue of how to better recruit and retain excellent public school teachers. Now is the time to re-shape outdated policies to convince the best and brightest to enter our classrooms—and piecemeal tinkering will not get us to this goal. Instead, a major transformation of how we recruit, recognize, and compensate teachers, all the way from initial student loan repayment incentives to providing a secure and portable retirement, is the only way to create a new cycle that will enable us to bring the teaching profession into the 21st century and ensure that the 3 million new teachers we hire over the next ten years are the best we’ve ever had.