Report Published May 15, 2014 · Updated May 15, 2014 · 21 minute read

The State of the Center

Michelle Diggles, Ph.D. & Lanae Erickson

For more on this subject, visit StateoftheCenter.org.

The ideological wings of both parties often characterize Americans in the middle as “mushy,” lacking core convictions and unable to make up their minds. Our inaugural State of the Center poll deeply probed the animating values of those in the political middle, and the results offer a strikingly different interpretation of this crucial, diverse voting bloc. In short, moderates wrestle with, and often reject, what they see as the false either/or ideological choices that define modern politics. They recognize that both sides have a piece of the truth and see flaws in the standard liberal and conservative perspectives, which are evident in moderate’s views about government, politics, and policy issues. And while they currently lean towards the Democratic Party, distinctions between moderate and liberal values provide a significant opening for Republicans to appeal to them.

This coming November, candidates, party committees, and Super PACs will spend hundreds of millions of dollars to convince liberal and conservative voters to do one thing: vote. For moderates, the question isn’t just whether to vote; it’s for whom to vote. They are the persuadables in an electorate often characterized as completely polarized between voters on two sides who have already made up their minds.

Our State of the Center poll digs deeply into competing moderate values. We found, for example, that moderates support government and want it to work; and they might even align with liberals if government worked as well as liberals think it does. But it doesn’t. On the other hand, they believe in the free market and individual responsibility; and they might align with conservatives if the free market created the equality of opportunity conservatives think it does. But it doesn’t. Moderates are not wishy-washy, disengaged, or ill-informed. They are viewing politics without the benefit of ideological blinders and struggling with values that pull them crosswise.

I. Who are moderates?

Moderates make up a significant chunk of the electorate, comprising 37% of registered voters in our poll, compared to 21% who are liberals and 42% who are conservatives. Four in ten moderates are self-described Democrats and a nearly identical number are Independents (39%). Just 21% of moderates are Republicans. This asymmetry significantly impacts the make-up of the party coalitions. The Democratic Party is split, with 38% identifying as liberal, 37% as moderate, and 25% as conservative. By contrast, nearly three-quarters (72%) of the Republican Party identifies as conservative, with only 26% saying they are moderate. As for Independents, nearly half (48%) are moderates, with 18% calling themselves liberal and 34% conservative.

Many of the demographic groups who have recently been increasing their share of the electorate are overrepresented in the center. For example, moderates are a racially and ethnically diverse group. Thirty-seven percent identify as nonwhite or Hispanic, compared to 30% for liberals and 25% for conservatives. Among all nonwhite and Hispanic respondents in our survey, a plurality of 44% described their ideology as moderate, with 35% saying they are conservative and 21% liberal. By contrast, non-Hispanic whites skewed more conservative (46%) over moderate (33%). Millennials also trended more moderate, with a plurality (42%) calling themselves such, compared to 37% of the general population—making them the single most moderate generation in our poll.

II. Moderates on the Role of Government

Moderates are hopeful but skeptical about government.

Moderates adopt a much less ideological view of the size of government than either liberals or conservatives. More than half (54%) of liberals favor a larger government providing more services, compared to only 12% who wish the government was smaller. By contrast, 62% of conservatives favor a smaller government providing fewer services to a mere 13% who would prefer a bigger government. Among moderates, a plurality (39%) say they do not think of government in those terms, with another 37% favoring a smaller government (25 points lower than self-described conservatives) and 23% a larger one (31 points lower than self-described liberals).

This non-ideological approach to government is born out in moderates’ assessment of specifics things the government should do, as well as where they believe the government’s effectiveness is limited. For example, 53% of moderates worry that the government is not doing enough for the economy, with only 40% worried about too much government involvement in the economy. Liberals and conservatives adopt much more ideologically-aligned positions, with 75% of liberals worried about not enough government involvement and 60% of conservatives worried about too much.

Reflecting this ideological ambiguity, moderates hold serious reservations about government efficacy. Nearly two-thirds (64%) think government is often an obstacle to economic growth and opportunity, while 34% disagree. Liberals feel the opposite and disagree by a 19 point margin, (conservatives agree by a staggering 71 points). By 11 points (54% to 43%), moderates think if the government is involved in something, it often goes wrong—three-quarters of conservatives also agree, but 64% of liberals disagree with that statement. Moderates tilt towards big government as a greater threat to our country (52%) than big business (41%), and still again, liberals tilt strongly in the opposite direction (66% big business), while 8 in 10 conservatives worry more about big government. Given these views, it is unsurprising that moderates believe charity does a better job at helping people than the government (67% to 29%).

III. Moderates on Politics

Liberals and conservatives think their own parties are moderate, but moderates don’t.

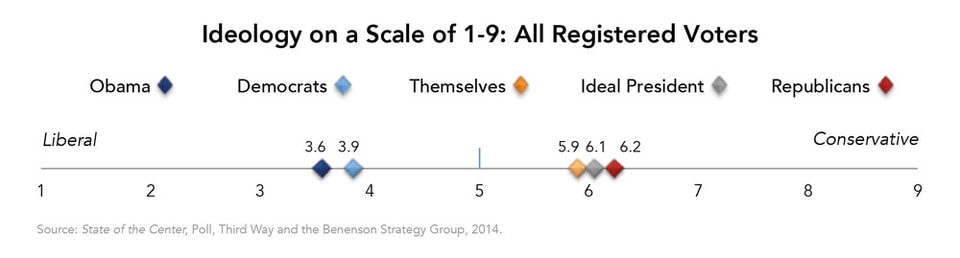

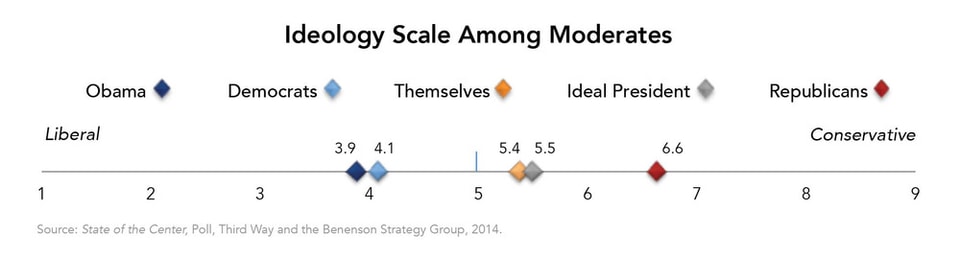

When asked to rank themselves on an ideological scale from 1 to 9, where 1 is liberal, 5 is moderate, and 9 is conservative, moderates placed themselves just to the right of center at 5.37. Liberals put themselves more than one point to the left of center at 3.88. And conservatives rated themselves as more than 2 points from the center at 7.39—meaning they identify as much more to the right than liberals do to the left.

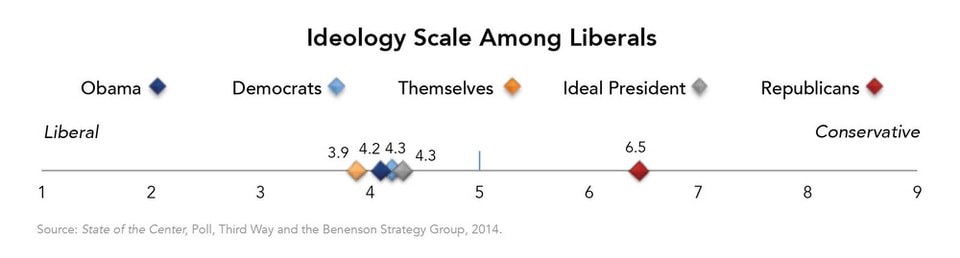

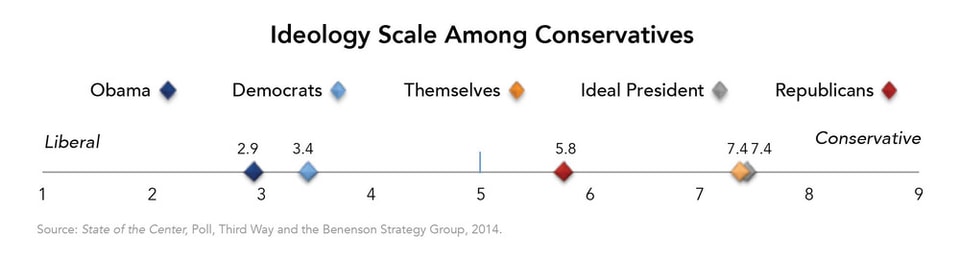

On their partisan assessments, those on the left and the right display some similarities. Liberals and conservatives rate Democrats and Republicans in Congress, respectively, as much more moderate than they rate themselves. Liberals place Democrats in Congress at 4.27, left of center, but to the right of the 3.88 mark where they put their own ideology. Another way of looking at this is to say that liberals don’t think congressional Democrats or the President are liberal enough. Conservatives place Republicans in Congress at 5.76, right of center, but not nearly as conservative as they rate their own beliefs—they feel that congressional Republicans are not nearly conservative enough.

By contrast, moderates viewed the parties as more ideological than they saw themselves, and they also perceived the parties as further toward their respective ideological extremes than was attributed by voters in each party’s ideological wing. On the 1 to 9 scale, moderates placed Democrats in Congress at 4.08 and Republicans at 6.63—an almost perfectly symmetrical positioning compared to their own place on the scale (1.29 and 1.26 away to the left and right, respectively). Moderates also believe that President Obama is even more liberal than Congressional Democrats, placing him at 3.88.

This difference in perception is evident when moderates were asked to describe Democrats and Republicans using three labels: liberal, moderate, or conservative. Half of moderates said President Obama is a liberal—a view shared by 69% of conservatives—and only 36% say he’s a moderate. But liberals are torn, with 51% saying he’s either a moderate (44%) or a conservative (7%), and only 43% calling the President a liberal. Further, 58% of liberals think Congressional Democrats are moderates, but a plurality of moderates (43%) think Democrats in Congress are liberal. On the other side, 42% of conservatives think Congressional Republicans are moderates, with another 36% saying they are conservative. But two-thirds of moderates think Congressional Republicans are conservatives.

Liberals view Democratic leaders as less liberal than the rest of the electorate sees them. Likewise, conservatives view Republicans as less conservative than they are according to others. Moderates see both parties as further out on the wings than either ideological wing views their own leaders. In short, the left and right on the ideological spectrum believe their own partisans are moderate—but that view is not shared by the middle.

Liberals and conservatives stick with their party, but moderates are persuadable.

Despite critiques by liberals and conservatives that their partisan leaders aren’t ideological enough, they side with their respective parties in a contest against the other. But moderates are much more torn. We can see this trend when assessing the characteristics associated with Democrats and Republicans. Sixty-nine percent of liberals say the term “accountable” applies more to Democrats, while 57% of conservatives say it applies more to Republicans. Moderates are not sold on either party—39% say it applies more to Democrats, 31% to Republicans, and 27% say neither (20%) or that they aren’t sure (7%). Similarly, 69% of liberals say the term “practical” describes Democrats; 59% of conservatives say it describes Republicans. Here moderates split again with 40% saying Republicans and 38% applying it to Democrats.

This tendency also emerges in voting behavior. Few liberals (17%) and conservatives (20%) say they vote for candidates from the other party. But one-third of moderates say they vote equally for Democrats and Republicans, while only one-third say they almost always vote for the same side (24% for Democrats and 9% for Republicans). Contrast this to 51% of liberals who almost always vote for Democrats and 39% of conservatives who say the same about Republicans.

Moderates’ openness to candidates from either party was reflected in another data point as well. Whereas nearly identical numbers of liberals (42%) and conservatives (41%) said they can decide which candidate to support from party labels alone, only 31% of moderates agree. Strikingly 40% of moderates strongly disagree with the notion that party labels tell them all they need to know about a candidate. Fully two-thirds of moderates say party labels are insufficient to determine their vote, positioning themselves as more open to appeals from candidates on both sides.

Moderates are politically engaged but worry about a “my way or the highway” approach to politics.

Despite the preconceived notion that voters in the middle are disengaged, there is virtually no difference between moderates (35%), conservatives (34%), and liberals (31%) on how many say they tune out politics. Rather, nearly two-thirds of each group disagrees with this statement: “Politics do not really affect my life and I tune out most discussions about politics.” But the devolving nature of political discourse is having some effect on Americans in the middle: 62% of moderates say they actively avoid political discussions because of divisiveness, while 57% of liberals and 53% of conservatives say the same. Interestingly, one-quarter of conservatives strongly disagree with this point—10 points higher than among moderates—which may indicate that conservatives are more willing to engage in divisive political discussions. However, those in the ideological bases may also be more likely to surround themselves with like-minded people—8 of 10 moderates say they don’t find it hard to be around people who disagree with them about politics, compared to 71% of liberals and 67% of conservatives.

Reflecting these values, voters of all ideologies stress compromise even if it seems in rare supply in Washington. Eighty-six percent of moderates and 85% of liberals think people who cannot compromise shouldn’t be in politics. Even 75% of conservatives agree. However, twice as many conservatives (23%) as moderates (11%) believe that compromise is not a virtue in politics.

IV. Moderates on Opportunity

Moderates think that the deck is stacked against some people but not against themselves personally.

In contrast to conservatives, moderates still believe there are hurdles to equal opportunity in America. Three-quarters of moderates agree that America is divided into haves and have-nots—10 points less than among liberals, but 18 points higher than among conservatives. They align more closely with liberals on why people are poor. Among moderates, 58% disagree with the view that people are poor because of bad choices (a statement with which 60% of conservatives agree). And when asked whether discrimination against racial minorities is mostly a thing of the past, only 28% of moderates said it was, a stark contrast to the 43% of conservatives who agreed (20% strongly, compared to 6% among moderates).

Though moderates believe equal opportunity has not been achieved, 85% believe that most people can get ahead in America if they work hard, with 49% strongly agreeing with that statement. These numbers mirror conservative beliefs in the efficacy of hard work (91%) and illustrate that while moderates believe that some real barriers to equal opportunity remain, they do not think those barriers are so overwhelming as to inhibit most people from being successful if they put in the effort.

Importantly, moderates do not feel the deck is stacked against themselves personally. Only 28% of moderates agree that “the deck is stacked against people like me,” and 4 times as many strongly disagree (40%) as strongly agree (10%) with that statement. Overwhelmingly, liberals (69%) and moderates (69%) both rejected the notion that they are personally impacted by structural inequalities, as did a smaller but solid 63% of conservatives (interestingly, conservatives were the most likely to say the deck was stacked against them personally, at 35%). And when asked explicitly whether they considered themselves to be a “have” or a “have-not,” few liberals (35%), moderates (25%), or conservatives (17%) place themselves in the latter category.

In fact, most moderates view themselves as financially similar to average Americans (52%) and people in their community (62%), and another quarter said they were better off than each. Only 11% think they are worse off than people in their own community, and only 23% said the same about the average American. Liberals locate themselves similarly, though 30% think they are better off financially than the average American and 41% about the same (those numbers are 23% and 66% compared to people in their own community). Conservatives rank themselves nearly identically to moderates. And there is one more thing liberals, moderates, and conservatives can agree upon: about three-fourths of each say that they are worse off financially than Members of Congress. This means that when it comes to providing greater economic fairness, Members of Congress may be poor messengers.

Despite seeing themselves as having broad opportunity, moderates believe the government should and can be generous to those who lack it. Eighty-five percent of moderates agree that the government has an important role to play in ensuring that everyone, regardless of race, gender, or age, has an equal opportunity to succeed in this country. Liberals are unified on this point as well, with 92% agreeing. While 73% of conservatives also agree, passion is diminished and 18% strongly disagree—compared with 5% of moderates and 3% of liberals. Seven in 10 moderates agree that “it is better to have a strong safety net even if means a few lazy people game the system than to let those who truly need help go hungry or end up homeless.” On this point, liberal support is identical to moderates, whereas conservative support plummets 20 points.

At the same time, though, moderates express concern over the potential for negative consequences with too much government support. As we noted above, just over half of moderates believe that when the government is involved, things are likely to go wrong—potentially explaining their belief that charity is more effective at helping people than government. Further, 61% moderates agree that “the government has created too many incentives for poor people not to work.” Liberals feel the opposite: just 31% think the government has incentivized poverty over work and two-thirds disagree—42% strongly (compared to only 18% among moderates). While moderates value the safety net and are sympathetic to concerns about structural inequalities, they believe there is some truth in the potential for negative consequences and lean heavily into emphasizing hard work and personal responsibility—which is how Republicans have attracted some moderate support in the past.

V. Moderates on the Economy

Moderates support government investment and deficit reduction.

Moderates support Democratic calls for investments that would grow the economy, but to them, debt and deficits are dirty words. Nearly three-quarters (72%) agree that “we need to increase investments in infrastructure and education rather than worrying about long-term debt.” In this regard, they are similar to liberals (81% agree) and very different from conservatives (54% agree). But an even larger portion of moderates (77%) agrees that “it’s immoral to leave our children a country that is 17 trillion dollars in debt.” Here moderates are wrestling with competing values and priorities. Given the data above, 51% of moderates agreed with both of those two statements.

When asked to name their biggest concern about Democrats being in control of government, moderates worried that Democrats would not fix the deficit and pay down the debt (32%). Another 28% expressed concern about government spending on programs that don’t benefit them or their family. Together, this suggests that 60% of moderates are worried about Democratic fiscal decision-making. By contrast, 37% of liberals say their biggest concern would be Democrats not fighting hard enough for liberal priorities, with lack of action on the deficit and debt coming in second at 35%.

Moderates worry that if Republicans were in control of the government, they would be hurt by Republican financial decision-making that would shortchange investments in the economy and threaten safety net programs for the poor and middle class. Nearly three in ten (29%) moderates said their biggest concern with Republican control of government would be a lack of economic policies to spur growth and help the middle class. Another 26% worried that Republicans would cut government programs their family relies upon, such as financial aid, social security, or unemployment benefits. While liberals express similar concerns about Republicans as do moderates, their chief concern (38%) is that Republicans would eliminate rules that protect the environment and consumers as well as rules that rein in banks that caused the financial crisis. By contrast, a plurality of conservatives (36%) worry that Republicans wouldn’t fight hard enough for conservative priorities.

Reflecting these tensions on economic decision-making, moderates are torn about which party is focused on economic growth—43% select Democrats and 40% say Republicans. By contrast, two-thirds of liberals pick the Democratic Party and two-thirds of conservatives pick the Republican Party. On economic issues, liberals and conservatives give their preferred party the benefit of the doubt, but moderates aren’t so sure either has the right recipe.

VI. Moderates on Key Issues

On a series of specific issues, we found moderates weighing competing values and considering both positive and negative consequences for policies they generally support. This tension sometimes translates into support for policies that may seem at odds with each other to those in the more ideological camps. And it demonstrates how each party can misinterpret moderate positions if they only pay attention to the piece of moderate values that validates their own ideological perspective.

Energy: Immediate Gratification AND Long-Term Consequences

Three-quarters of moderates support expanding exploration and production of oil, coal, and natural gas in the U.S.—a position also shared by 64% of liberals and 92% of conservatives. But 90% of moderates also think we need to invest more in the development of renewable energy sources like solar and wind—a position shared by 97% of liberals and 70% of conservatives. Liberal passion is the highest, with 85% in strong agreement, compared to an impressive 62% of moderates who strongly agree. Moderates truly support an all-of-the-above energy strategy, which is evident if partisans examine both sides of this coin.

Immigration: Compassion AND Justice

There is broad agreement among liberals (93%) and moderates (84%) that undocumented immigrants are hardworking people trying to care for their families, and on that point, even 72% of conservatives agree. Yet moderates are deeply torn on the question of whether granting citizenship would reward bad behavior (47% agree compared to 50% who disagree). Conservatives aren’t torn: they overwhelmingly believe that granting citizenship to undocumented immigrants would reward bad behavior (68% agree to 30% disagree). Liberals adopt the opposite view (35% agree to 62% disagree). Further, while liberals think we spend too much on border security by 17 points, both moderates and conservatives disagree—by 14 and 39 points respectively. Moderates are sympathetic to undocumented immigrants and believe they are good people, yet these voters also worry about encouraging lawlessness and maintaining security at the border. They would support comprehensive immigration reform that is tough, fair, and practical, reflecting that tension.

National Security: Safety AND Privacy

On national security, all ideological groups feel the scales have tipped too much towards public safety over civil liberties. Nearly identical proportions of liberals (76%), moderates (71%), and conservatives (85%) worry that the government is going too far in collecting information about people’s phone and internet usage—although passion is strongest among conservatives, 60% of whom agree strongly. Yet liberals and conservatives have very different feelings about terrorism—likely reflecting their partisan views about the Commander in Chief. While 63% of conservatives worry we aren’t doing enough to stop terror attacks on U.S. soil, 65% of liberals disagree. Moderates are torn on this question, with 45% saying they worry and 52% saying that doesn’t concern them. The post-September 11th consensus on civil liberties and public safety may be rebalancing, but for now, moderates remain torn.

Culture Issues: Individual Responsibility AND Government Protection

Our poll uncovered a current undergirding moderates’ views on many issues that have been central to the “culture wars” of the past few decades. On questions of individual behavior on issues from guns and abortion to healthy eating and marijuana use, we found that moderates wanted individuals to ultimately be responsible for the choices they make—not government. In our survey, only the subject of texting while driving elicited a response of people wanting more government ground rules (77%) compared to placing more trust in individuals to make the best choice (21%). This current may help explain a phenomenon that has frustrated advocates on some of these issues in the past: why do culture issues sometimes poll in one direction but feel like uphill political battles?

Our data showed that moderates support greater trust in individuals rather than more government intervention on a whole range of issues. For example, though polls repeatedly show our country starkly divided on the issue of abortion, only 14% of all respondents in our poll wanted to see more government ground rules on the decision to have an abortion, compared to 81% who prefer to trust individuals to make the right choice (84% among moderates). Voters believe the abortion issue has been decided, and they want to move on.

On guns, we found overwhelming supermajorities across the political spectrum in favor of expanding background checks for gun sales with liberals (93%), moderates (84%), and conservatives (72%) all in agreement. Yet voters were split about whether they wanted more government ground rules on guns (48%) or to put greater trust in individuals (50%). Moderates are more mixed, leaning in the direction of government involvement by a slim 53-44% margin, while liberals were adamant about the need for more government intervention (78-20%).

Another complicating dynamic on guns was evident on the question of whether our current gun laws are sufficient to protect the respondent and their community. Two-thirds of liberals said current laws aren’t sufficient, while 76% of conservatives said they are. And passion was high on this issue—44% of conservatives strongly believed current laws are sufficient, compared to 45% of liberals who strongly disagreed. Meanwhile, 58% of moderates thought current gun laws are sufficient, while 40% disagree—even while 53% of moderates think we need more government ground rules on guns.

Moderates support expanded background checks, to be sure, but they don’t seem to necessarily believe that policy is crucial to protect themselves at home or in their own communities, where they are comfortable with the status quo. This may in part be due to differences in patterns of gun ownership. Whereas more moderates (38%) own guns than liberals (30%), many more conservatives (50%) count themselves among the ranks of gun owners.

When it came to the issue of recreational marijuana use, moderates were torn but still emphasized individual trust (53%) over increased rules (42%), tracking closely with the population overall on those numbers (54-40%). This tendency toward trusting individuals rather than desiring stronger governmental ground rules may advantage the liberal side on marijuana legalization, as it seems to do on abortion and possibly on other issues like marriage for gay couples. But on others, like guns, it may make the road more difficult for Democrats.

Conclusion

Both Democrats and Republicans claim that moderates align with them on many of their favored issues—and our inaugural State of the Center poll shows there is some truth to that assumption. But the mistake each side makes is to hold up their favored piece of moderate values while ignoring the tensions inherent in the moderate perspective. Moderates think both sides have a piece of the truth and can see deficiencies in relying solely on one or the other. They refuse to be pigeonholed into an ideological box, instead adopting informed—if often conflicted—views on politics and pressing public debates. Democrats rely on moderates more than Republicans to win elections, owing to the dearth of liberal compared to conservative voters. But both parties should be wary. Refusing to understand the full complexity of these voters, or assuming that agreement on one piece means a wholesale acceptance of a partisan worldview, could make their appeals fall on deaf ears with this crucial segment of the electorate.