Report Published June 25, 2015 · Updated June 25, 2015 · 17 minute read

Treating the Whole Person: Integrating Behavioral and Physical Health Care

David Kendall & Elizabeth Quill

Ashley Erickson grew up with constant worry and anxiety. She spent many days in the nurse’s room at school with stomachaches. Later as a student at the University of California, San Diego, she got the shakes and felt like she couldn’t breathe while watching a movie. An urgent care clinic X-rayed her, gave her an EKG, and tested extensively for chest issues. “I thought I was crazy when doctors told me they couldn’t find anything wrong,” she recalls.1 Fortunately, the school clinic where she was getting medical care also had a psychologist on staff who recognized her symptoms as panic attacks and diagnosed generalized anxiety disorder.

In addition to medications, the cure for Ashley was running. Her psychologist explained that running helps people control their breathing, which is very helpful during panic attacks. Ashley embraced it—and is now a marathon runner. The lesson from her experience is that when health care providers treat underlying mental health conditions instead of just the physical symptoms, people are healthier, happier, and often require fewer health care services. By adopting a strategy to integrate behavioral health care with medical care, the federal government could save as much as $40 billion over 10 years.

This idea brief is one of a series of Third Way proposals that cuts waste in health care by removing obstacles to quality patient care. This approach directly improves the patient experience—when patients stay healthy, or get better quicker, they need less care. Our proposals come from innovative ideas pioneered by health care professionals and organizations, and show how to scale successful pilots from red and blue states. Together, they make cutting waste a policy agenda instead of a mere slogan.

What Is Stopping Patients From Getting Quality Care?

All too often, health care professionals treat patients only for their physical conditions and not accompanying behavioral health conditions. But, patients with behavioral health conditions (which include mental health and substance abuse conditions) often return to the doctor again and again with similar physical problems related to the untreated behavioral condition—driving up health care costs. For example, one-fifth of patients who have just had a heart attack suffer from depression. When this depression is not treated, the chances of the patient dying from a future heart attack can triple.

Untreated depression prevents people from properly managing other chronic conditions—and often worsens their physical symptoms. These individuals repeatedly return to the doctor with similar physical problems related to the untreated behavioral condition. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), untreated depression is responsible for “considerable functional impairment, poor adherence to treatment, adverse health behaviors that complicate physical health problems, and excess health care costs.”2 In the 2003 National Comorbidity Survey Replication, more than 68% of adults with a mental disorder had at least one medical condition.3

Mental health problems also compound existing physical health problems and make it more difficult for individuals to care for themselves. Individuals with chronic conditions such as diabetes, arthritis, and heart disease are three times more likely to be suffering from depression.4 While many individuals experience depression as a result of living with their chronic disease, some people develop depression as a result of biologic effects of their chronic illness.5 These co-occurring physical and mental conditions, called comorbidity, result in substantial additional cost to the health care system. In 2011, 34 million adults (17% of American adults) had co-morbid mental health and medical conditions.6

People who are trapped with an undiagnosed or untreated behavioral health problem are not getting optimal care for three critical reasons:

- Lack of coordination between primary care and behavioral health care;

- Inadequate primary care for behavioral health; and

- Stigma about mental health conditions.

Lack of coordination between primary care and behavioral health care. The current system utilizes primary care to treat the symptoms of behavioral health rather than managing the behavioral health conditions. Even worse, in some states there are carve-outs that act as a wall between behavioral health treatment and primary care treatment and prevent coordination.7 For behavioral health care, these carve-outs are programs that contract directly with managed behavioral health organizations and are separate from the health care benefit package.8

Inadequate primary care for behavioral health. Even if individuals had access to better coordination of primary care and behavioral health care, the treatment of behavioral health conditions in primary care offices varies significantly from practice to practice.9 This is especially alarming because up to 70% of primary care visits are the result of behavioral health issues.10 According to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s national program, Depression in Primary Care, this variation can lead to unrecognized depression or treatment of depression “in ways that are inconsistent with evidence-based practice.”11 However, even when health care professionals have proper training to manage depression, “they face multiple competing demands for their attention and receive little or no financial incentive to manage depression.”12

Mental health stigma. The fight to eliminate the stigma of mental health conditions and treatment is far from won. Even with increased awareness of mental health conditions, there is a far greater stigma attached to these conditions versus physical conditions.13 Studies have shown this stigma causes people to curtail behavioral health treatments.14 It also frequently leads people to delay seeking necessary treatment for their depression, hoping to work out their issues on their own. They miss mental health care appointments more often than they do for appointments with primary care doctors and specialists.15 Delaying appropriate mental health care can be dangerous and leads to a host of problems including reduced productivity in the workforce and increased diseases from other causes.16

Where Are Innovations Happening?

Some states have successfully implemented demonstrations using integrated behavioral health professionals. For example, DIAMOND (which stands for Depression Improvement Across Minnesota, Offering a New Direction), a partnership of medical groups is based on a model called IMPACT: Improving Mood: Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment. It features a care manager “who provides ongoing assessment, a patient registry, use of self-management techniques, and the provision of psychiatric consultation.”17 This collaboration has improved patient outcomes tremendously when compared to patients receiving standard uncoordinated care. The project has successfully experimented with case rate payments with Minnesota health plans paying “a monthly PMPM [per-member-per-month payment] to participating clinics for a bundle of services—including the care manager and consulting psychiatrist roles—under a single billing code.”18

The Mercy Health system, located in Ohio and Kentucky, has recently started a new pilot program at its primary care offices with the purpose of screening all adult patients for depression. This effort is in response to the evidence that treating depression in conjunction with other diseases can increase medication adherence, rehabilitation efforts, and lifestyle change.19 Mercy screens patients with two simple questions and then refers them to one of the embedded behavioral health specialists on site. Patients receive eight brief, focused visits with a behavioral health specialist.20

In May 2014, Florida Blue began an Integrated Care Management initiative aimed at coordinating mental health, substance abuse, and chronic conditions for Medicare Advantage (MA) beneficiaries.21 Participating beneficiaries are offered coordinated medical and behavioral health support, and they create individual care plans with their interdisciplinary care management team for more effective treatment.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) also included provisions for demonstration projects for integrating behavioral health into medical homes within Medicare and Medicaid.22 Colorado received a significant grant from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation in order to pursue a statewide behavioral health initiative. The Colorado State Innovation Model (SIM) is aimed at lowering costs and improving care and health of Colorado residents.23 According to the Commonwealth Fund, the grant will “support the formation of integrated primary care within the state’s Medicaid ACOs with payment incentives based on readiness to accept risk and integration of behavioral and clinical care.”24 The goal of the program is to have 80% of residents in 2019 with access to integrated care for behavioral health and primary care in primary care settings. The estimated savings from this project reaches approximately $330 million over the course of five years.25

How Can We Bring Solutions To Scale?

High quality behavioral health care needs to be integrated with ongoing medical care. By doing this, we can ensure that providers are treating underlying problems rather than just symptoms—leading to healthier individuals and cost savings throughout the system. One study found that when older adults have coordinated behavioral health care, total health care costs go down by 10%.26 Furthermore, research has shown that physical symptoms often improve when behavioral conditions are treated properly.27 Public policy can accomplish this through two key changes: 1. Changing the delivery system through medical homes and bundled payments, and 2. Setting up overall accountability for optimal care using accountable care organizations and Medicaid managed care organizations. Both of these key changes are readily adaptable to a critical co-location and coordination features.

A co-location model is extremely effective because behavioral health professionals and primary care providers offer care at the same site.28 The easier it is to access behavioral health care at the same time as other care, individuals will be less likely to succumb to the stigma of treatment. With co-location, primary care professionals screen patients as part of an office visit29 and patients can then see a behavioral health specialist right after the primary care appointment either at the same office or nearby.30 The individual’s primary care office continues to coordinate the behavioral health care as needed.

One of the best examples of how the co-location model actually works can be found through the Improving Mood: Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) study. Patients in the program had access to depression care managers31 who worked along with the patient’s primary care physician. The depression managers offered education about treatment options and subsequent treatment with either antidepressants or problem-solving treatments consisting of six to eight psychotherapy sessions.32 Participants in the program had 12.1% lower total health care costs during a four-year period than patients with usual care.33 Further, the IMPACT program and other similar integrated programs have been shown to “improve physical and behavioral health outcomes compared to traditional models, under which primary care and behavioral health services are delivered by separate providers and systems.”34

Policymakers can replicate the success of IMPACT, mentioned above, and better integrate high quality behavioral health care with current medical care through two steps:

First, ensure coordination between medical health and behavioral health care using the Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) and bundled payments:

The Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) focuses on coordinated care for patients and has been used to improve the primary care model. This may mean reminder calls from a nurse, a nutritional expert on staff, or support groups for those facing similar challenges. Medical homes also allow providers to take the extra time to communicate with the other providers patients may go to such as specialists, hospitals, or home health aides so that care is coordinated and patients avoid duplicated tests or conflicting advice.

Establishment of medical homes can be encouraged by changing the way health professionals are paid.35 This involves providing a lump sum payment for services that cover care coordination, and providing additional payment bonuses to primary care physicians and behavioral health professionals who show well-managed care and improved outcomes.36 Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) can help extend the reach of the delivery reform. These MCOs have more flexibility to pursue integration and other tools to support these efforts.37 In addition, Medicaid has begun an integration strategy as part of the ACA known as health homes, which aim to help people with two or more chronic illnesses and a serious and persistent mental health condition.38

The 2014 PCMH Standards and Guidelines published by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) included some standards on behavioral health treatment.39 These standards encourage co-location and integration of behavioral and physical health services. But these standards also need to include services similar to the IMPACT program—where individuals have a depression care manager who provides education, medication management support, and problem-solving treatment as part of primary care for up to twelve months.

Bundled payments reward doctors for providing high value care instead high volume care by paying them a fee for an entire episode of care (e.g. a knee replacement). Often this set fee is a single payment to one provider or organization who is then responsible for compensating the other clinicians who have agreed to work together—rather than Medicare reimbursing claims from each of them.40 This single fee lets a group of providers cover services that are not ordinarily covered under the claims in a fee-for-service system. For example, the bundled payment in the IMPACT program allows the group to customize the care for each person by hiring a case manager who serves as a sounding board for how each person feels about the care they may need.41

Health plans in the private sector have been experimenting with bundled payments for several years through initiatives like PROMETHEUS, which has a bundled payment pilot project,42 including bundles for depression care.43 The next step would be to implement a full-scale bundle designed for Collaborative Care for Depression (CCD).44 One study reviewed results from the IMPACT program and worked to translate the results into a bundle.45 The results of this study indicate that it would be best to have a minimum length of time receiving CCD as a precondition to receiving the initial bundle payment.46

Second, use accountable care organizations (ACOs) and managed care organizations (MCOs) to create accountability for integrating behavioral health and physical health care.

ACOs consist of a “network of doctors and hospitals that share financial and medical responsibility for providing coordinated care to people in hopes of limiting unnecessary spending.”47 ACOs in the Medicare program give providers the opportunity to increase compensation by improving patient outcomes and keeping people healthy.48

ACOs have built-in incentives to coordinate behavioral health and primary care, but the majority of ACOs have not achieved integration.49 Currently, ACOs have a performance measure aimed at measuring screening for depression50 and for creating a follow-up treatment plan.51 As a result, many ACOs are indeed screening for depression, however, few ACOs integrate behavioral health treatment into primary care.52 Simply put, ACOs are not assessing how treatment works in each patient.

Having ACOs measure the actual outcomes of the care received by people with behavioral health issues would encourage ACOs to coordinate behavioral health care with medical care. It would also encourage provider groups to improve the treatment of depression for patients with chronic and other co-occurring conditions.53 Such an outcome measure is also critical for evaluating the quality of behavioral health care provided through medical homes and bundled payments. The federal government and states could encourage such accountability widely by requiring quality measurement reporting of health plan in Medicare and in private coverage through the Affordable Care Act’s exchanges.

The strategy for Medicaid would be to expand the use of MCOs, which provide coverage for long-term services and support to older adults and individuals with disabilities in 26 states.54 MCOs aim to improve care quality and contain costs. Approximately 70% of Medicaid enrollees are served through MCOs.55 Although mental illness is twice as common among Medicaid beneficiaries compared to the general population, the level of Medicaid services for differing kinds of behavioral health problems that range from serious mental illness to substance abuse to mild depression are not consistent. Generally, the care for the full range of behavioral health issues is not integrated with physical health care. That is where MCOs can help.56 MCOs have particular strengths including benefit design, comprehensive data summaries, and network development. MCOs can support ACOs through care management, population management, outreach and enrollment, patient engagement and education, process performance improvement, aligned incentives, and shared savings. All states should adopt such a strategy.

Potential Savings

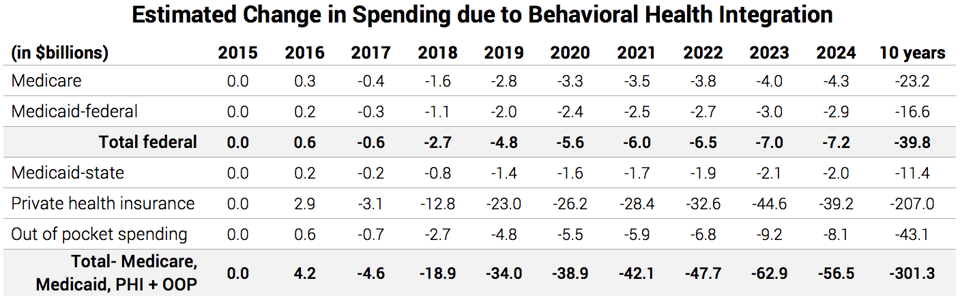

Based on analyses from the IMPACT program and a Milliman American Psychiatric Association Report on the economic impact of integrated behavioral health care, Third Way estimates that the adoption of these programs will save $40 billion over the 2015-2024 federal budget window. Milliman studied the cost of behavioral health and medical care for individuals in commercial insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid in 2010, with costs trended forward to 2012. The estimate is also based on four additional studies including a meta-analysis of cost-effectiveness research studies based on 23 other studies addressing the economics of collaborative care over the past three decades.57 Even greater savings are possible in private spending, which includes employer-based coverage, the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces, and other individual coverage. Upwards of $207 billion over ten years is possible because untreated behavioral health problems are even more prevalent among the non-elderly.

Questions and Responses

What about individuals with severe mental illness?

Congress should provide states with funding for the establishment of assertive community treatment (ACT) teams in all communities across the country.58 ACT is a team-based model of providing highly individualized services to those living with severe mental illness in the community. Supporting people to locate and access stable housing and work toward employment is equally important to an individual’s success as the behavioral health and physical health care they need. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) advocates for this model, which the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) also endorses as an evidence-based practice.59 Research repeatedly affirms that, when targeted to those with severe mental illness, ACT reduces hospitalization, increases housing stability, and improves quality of life for participants.60

How can Medicaid adopt proposals for integrating behavioral health and physical health care?

States need to pay for coordinated behavioral health treatment as proposed for Medicare. Mental illness is quite prevalent in the Medicaid population as approximately 49% of beneficiaries with disabilities have a psychiatric illness.61 Rates of depression are especially acute for the dual eligible population, people who qualify for Medicare and Medicaid. Rates of depression for the Medicaid population are estimated at 20% while the dual eligible population is estimated at 23%.62 The decision by many states not to expand Medicaid has left about 3 million low-income Americans without adequate access to care.63

There have been a number of demonstrations of coordinated behavioral health care for Medicaid beneficiaries that have improved patient outcomes and reduced health care costs. For instance, a pilot in Pennsylvania found that coordinating care for six months for Medicaid beneficiaries with behavioral health and at least one chronic medical condition significantly reduced emergency department visits and psychiatric inpatient admissions.64

In 2009, Tennessee’s Medicaid program fully integrated coverage for physical and behavioral health services through MCOs under a federal waiver.65 Two MCOs for the three major regions of the state operate the integrated system under a full-risk, capitated payment that covers all services.66 Tennessee allows MCOs the flexibility to manage behavioral health services with subcontractors who are embedded in the MCO’s offices so that the administration of all health care services are coordinated.67 The MCOs also reduce red-tape for primary care and behavioral health providers by making same-day payments to providers in order to encourage their participation.

Isn’t the lack of federal support for electronic health records for behavioral health professionals an obstacle to integration?

Yes, several types of providers including many behavioral health professionals were not eligible for federal incentive payments to health care providers for electronic health record adoption under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.68 Reps. Tim Murphy (R-PA) and Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX) have introduced the Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, which would—among many other positive measures for improving mental health care—advance integration by extending incentives to behavioral health providers so they can coordinate care with primary care providers through electronic health records.69 Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) is working on similar legislation.70

What about getting adoption in employer coverage and exchange coverage?

Federal and state exchanges can adopt outcome measures for health plans operating on the exchange in order to encourage integrated care. States can work through exchanges and multi-payer initiatives, like that in Colorado, to ensure adoption in employer coverage.

Didn’t the Affordable Care Act fix the issues with Americans receiving mental health care?

The ACA and previous legislation have largely ended the lack of parity in coverage between mental illness and physical illness, but coverage hasn’t yet dramatically increased access. The ACA declared the treatment of mental health an essential benefit but people have still been dealing with lack of access to behavioral health providers. It is necessary to ensure that people have access through the three delivery models and can get the required care needed.