Memo Published July 20, 2020 · 14 minute read

Why We Should Double the Pell Grant

Shelbe Klebs

The crisis brought on by the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has already significantly impacted the finances of students in higher education and their families. With the unemployment rate at its highest levels since the Great Depression and questions surrounding colleges’ ability to get back up and running this fall continuing to mount, there is deepening uncertainty around how Americans will be able to afford a college education in the years to come.1Many students and their families are rethinking their postsecondary plans for the fall; some may forgo college temporarily or permanently to work to support their families while others may choose to attend a more affordable community college close to home instead of a pricier four year school farther away—especially if courses at both will be taught remotely.2

What is certain, however, is that all students will need greater access to stable federal financial aid that can keep the option of postsecondary education open and available to them now and in the years ahead. So far, Congress has allocated $14 billion to higher education,with half of that going to students as emergency aid.3But it’s up to institutions to figure out how to distribute that aid to students, and a lack of decisive, transparent guidance from Education Secretary Betsy DeVos casts major doubt on whether or not this money will end up in the hands of students who need it the most.

We also know that this initial infusion of money will not be enough to support students struggling financially during this crisis. But as Congress considers ways it can best give our financial aid system a boost, one idea—which has the support of over 80 organizations, institutional leaders, and a broad coalition of likely voters—is to double down on the currently-existing mechanism in federal law designed to target funding to low-income students by doubling the maximum Pell Grant award available to students.4

Taking this step would not only help students currently in crisis but also significantly boost the grant’s purchasing power to help more low- and moderate-income students afford college for years to come. Many students will continue to feel the ramifications of COVID-19 beyond the next school year, making the time ripe to permanently invest in a financial aid program that goes directly to high-need students. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel: Pell Grants already have a track record of helping students both access and complete education beyond high school. This memo will provide a brief background on what the Pell Grant is and the long-term impacts growing this investment could have for students and taxpayers.

What is the Pell Grant?

The Pell Grant is the foundation of our federal financial aid programs. It has been around for nearly 50 years with the explicit goal of increasing access to college for low- and moderate-income students. These crucial grants focus entirely on a student’s financial need, do not have to be repaid,and can be used for the equivalent of 12 full-time semesters. Students must complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) in order to receive a Pell Grant, as this determines their eligibility and award level. Filling out the FAFSA provides the answers needed to calculate a student’s Expected Family Contribution (EFC) through the needs analysis formula, which helps determine if and how much a student will be awarded.5A student’s EFC is a measure of their family’s financial strength and is considered an indicator of how much a student’s family can put toward college by the Department of Education.6If they are eligible for a grant, they can use it to pay for their tuition or to pay for other essential college-related costs like books and supplies, transportation, or room and board. To use the grant, students must be enrolled in a degree-granting program at an accredited institution.

The maximum Pell Grant award a student can receive for the 2020-21 school year is $6,345—an amount that Congress currently sets through the annual appropriations process.7Policymakers then appropriate a lump sum that will fully fund the program for that calendar year.8 This currently amounts to roughly $30 billion taxpayer investment in students.9 An additional stream of mandatory funding is used to supplement the program, and there is no limit on the total amount of funding available. This way, all eligible students who apply for an award will receive one.

Over seven million students (or roughly 40% of undergraduates) receive a Pell Grant each year, with a majority of recipients attending public institutions.10 This program is the largest source of grants for students trying to attend a higher education institution and opens the door for many students who could not otherwise afford it. Because the program is so well targeted, most funding goes to students who truly need it: around 75% of Pell dollars go to students whose family incomes are below $30,000, and 95% of recipients have family incomes below $60,000.11 It’s the built-in mechanism we have at the federal level to distribute aid to our neediest students in a targeted and efficient way.

Pell Grants also greatly benefit the diverse nature of today’s students on campuses across the country. In 2015, 53% of Pell recipients were considered financially independent, and more than half of these students had dependents themselves.12 And 45% of Pell recipients were over the age of 24. Pell students are also more likely to be students of color or first-generation, in addition to being low-income per the eligibility guidelines. Further, around 40% of Pell Grant recipients are veterans. The Pell Grant makes it possible for students in all stages of their lives to attend college with reduced reliance on hefty student loans.

How would Doubling the Pell Grant Impact Students?

When advocates say,“double the Pell Grant,” they mean making the maximum award twice the size it is now. There are various ways Congress can do this, including changing eligibility for those who can receive this grant. Appendix A at the bottom of this memo highlights four of the options currently on the table. Regardless of how Congress chooses to make this change, advocates agree that doubling the maximum award would greatly expand the reach and effectiveness of the Pell Grant, helping to fulfill Congress’ original intent of the program: to make college available and affordable to all students.

Doubling the Pell Grant would restore its purchasing power.

Right now, the Pell Grant only covers around 30% of a college education. It used to cover 80%, but its purchasing power has eroded significantly over time.13 That’s because when students go to college, they don’t just have to pay for tuition and fees. They also have related costs like transportation, housing, and food, among others. And while schools have become drastically more expensive, more than doubling tuition costs over recent decades, Congress’ funding of the Pell Grant has not kept pace.14 Right now, the Pell Grant is often only enough to make attending some community colleges more affordable, but it cannot cover the total direct costs of attending a two- or four-year degree program, not to mention all of the other expenses that students incur in their pursuit of an education.15 Research from the National College Attainment Network (NCAN) found that only 45% of community colleges are “affordable” to Pell Grant recipients, with a mere 25% of public four-year institutions meeting this benchmark during the 2017-18 school year.16

This decline in purchasing power correlates with decades of state budget cuts for public higher education and sharply increasing college costs across all sectors and types of colleges. Many low-income students currently close the gap between available aid and total expenses by taking out more federal loans.17 While federal student loans can be a critical access tool and pay off for most borrowers over time relying heavily on loans disproportionately saddles low-income students with debt that they are more likely to struggle to repay, potentially leading to longer-term issues like an inability to buy a house or poor credit.18 Given the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, low-income students may be more likely to struggle to repay loans because of lost jobs and income. Doubling the grant could reverse this trend, allowing Pell to make up a greater share of the cost of college to ensure recipients don’t just enroll in school but graduate as well.

Doubling the Pell Grant would expand the program’s reach for millions of students, particularly students of color.

In addition to restoring its purchasing power, doubling the maximum Pell Grant award also presents an opportunity to expand the number of students who could access the Pell Grant, most notably, students of color. Modeling from the Urban Institute found that doubling the Pell Grant would allow students of color to see large increases in the amount of their average grant award.19 For example, their estimate (which follows option 2 in the appendix below) shows that doubling the maximum Pell Grant would increase the average award received by Black and Hispanic students by over $2,000. White and Asian students would also see an increase, but at a more moderate rate. This would result in a substantial increase in the amount of money available to cover the full costs of college and represent an important federal investment in students of color—who are disproportionately more likely to struggle with high student loan balances than their white peers.20

Doubling the Pell Grant would improve student outcomes.

In addition to increasing access to postsecondary education by making it more affordable for more students, doubling the Pell Grant would also have the ripple effect of improving postsecondary outcomes for the students who do enroll. According to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, receiving a Pell Grant can reduce dropout rates and increase persistence rates for students.21 They found that a $1,000 increase to the award increased retention rates among recipients by 1.5 percentage points and increased enrollment by up to five percentage points.22 Plus, it decreased dropout rates by up to nine percentage points.23

In another study conducted on California state aid, researchers interested in understanding the impact of increasing aid on outcomes for students found that Cal Grant recipient the largest state financial aid program for students in the country were more likely to transfer to four-year institutions, complete college, and see a spike in long-term earnings.24 Having access to additional grant money increased students’ chances of getting a bachelor’s degree by 4.6 percentage points, getting a graduate degree by 3.1 percentage points, and seeing an earnings increase by “1.3 percentile points in the income distribution.”25 It’s also well-documented that students who receive a Pell Grant work less, enroll in more courses, and are more likely to attend college full-time—all of which increase a student’s likelihood of graduating.26 This indicates that even modest increases to the Pell Grant and other grants like it improve student outcomes in higher ed. It’s likely that a larger increase, like doubling the maximum award, would exponentially improve the outcomes of low-income students.

Doubling the Pell Grant would Pay for Itself in the Long Run

Doubling the Pell Grant may seem like a large expense for taxpayers to bear, but prior research finds that this effort will pay for itself in the long run. A recent report by Jeffrey T. Denning, Benjamin M. Marx, and Lesley J. Turner found this return likely using Texas colleges and universities as an example. Overall, they found that at four-year institutions, access to greater amounts of grant aid increased enrollment, completion rates, and earnings for first-time students attending those schools.27 Without considering the higher completion rates (which are correlated with higher income), the study found that the increased earnings alone are enough for the government to recapture its expenditures within 10 years, suggesting that investing in additional grant aid will pay for itself over time. This is in part because college graduates pay more in taxes, which will help the government make up what it spent on the program.

Conclusion

COVID-19 blindsided all of us, but here are several policies Congress and the next administration could enact to quickly help students in the aftermath of this crisis. Doubling the Pell Grant is the most straightforward option Congress has on the table—and it has the added benefit of targeting aid in a way that’s less regressive than other options like free college. The Pell Grant has seen widespread bipartisan support since its inception and remains the built-in tool currently in federal law to target aid to students who need it most. Due to increased tuition and decreased state investment in higher education, the Pell Grant’s power to fund a college education has depreciated—especially at four-year schools. Congress has the chance now to right this ship and restore power to Pell, both as an immediate fix to helping students navigate the current pandemic, but also as a permanent solution to making college more affordable for all.

Appendix

How Could Congress Double the Pell Grant?

Option 1: Double Pell Grant awards for all currently-eligible recipients, but do not change eligibility at all.

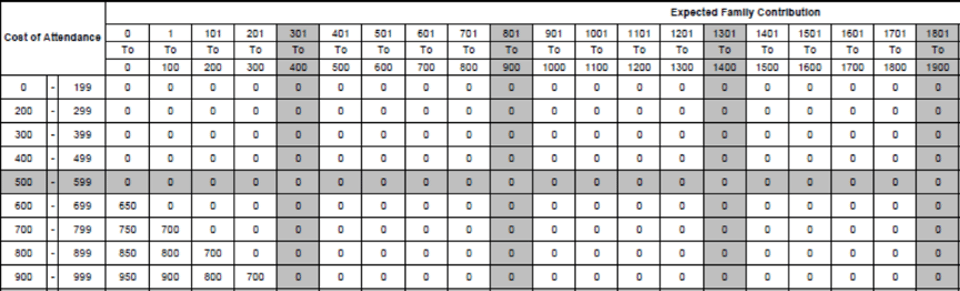

If Congress chooses this option, it could instruct the Office of Federal Student Aid to change the Pell Tables used to compare EFC and Pell Grant size so that they move in increments of $200 per box instead of the current $100 (see below for an example of a Pell Table).28 This would result in no change to which students are eligible for aid and not change who receives an award; the award would simply be larger for each currently eligible student. Going down this route is estimated to increase the cost from $30 billion to around $66 billion annually, which would more than double the program’s current allocation.29

Option 2: Double the maximum Pell Grant award and expand the Pell Tables so that it still moves in increments of $100, thus greatly increasing the income level of those eligible.

If Congress goes with Option 2, some students not previously eligible because their EFC is too great would become eligible for some portion of the grant. Choosing this option would increase the proportion of middle- and high-income students eligible for aid. In particular, researchers found that doubling the Pell Grant in this way would increase the number of eligible students whose family income falls between $75,000 and $92,000 from 13% to 40% and students from families with incomes between $92,000 and $112,700 receiving Pell would increase from 2% to 21%.30 This approach has faced some criticism by some because they feel it may not meet the mission of the program, which is to help make college affordable and accessible for students with the greatest financial need.

Option 3: Double the maximum Pell Grant award level and create an eligibility cut off so that more students are eligible for an award, but it does not expand fully to the upper-middle class.

Choosing this option would allow Congress to set an EFC maximum for Pell eligibility. Under current Pell Grant eligibility, all students applying must qualify for at least 10% of the maximum award to receive any award at all. Right now, that’s about $634. If you double the Pell Grant without adjusting this percentage or the process used to determine awards, it will expand the program to the middle class because more students would hit a 10% threshold of $12,190 (the proposed maximum amount if Pell is doubled). But, if the goal is to maintain the Pell Grant program’s focus on low-income students, you can increase this percentage to require students to be eligible for 25% of the maximum award to receive any award. This would expand the award to some lower-middle-income students, but it would not creep as far up the income chain as expanding the maximum award without adjusting the process at all. But, this method is not viewed favorably by all. Alternatively, rather than maintain a process that bottoms out the EFC at zero, some have proposed that Congress could create a negative EFC. With the current Pell Grant, a negative EFC will give the poorest students an EFC of -$6,345.31 This would allow low-income students to receive more money for college without expanding the program to middle-income students. This alternative has a similar effect to creating an eligibility cut off but is seen as a better way to go about it because it would more accurately account for and target funds to students who currently classify as having a zero EFC.32

Option 4: Double the maximum Pell Grant award level and create a new formula such as basing Pell eligibility on the percentage of the poverty level rather than EFC.

This is another option that Congress could use to double the amount of money students currently get from the Pell Grant without expanding the program to the upper-middle class. Basing the aid calculation on a student or family’s income compared to the federal poverty level would eliminate the need for the EFC formula and still allow Congress to target the program to low-income students without the concern that the additional investment would go to higher-income students.

Example Payment Schedule for 2020-2021 Full-Time Pell Grant Awards