College Administrators Support Greater Accountability in Higher Ed

The debate around a new Higher Education Act is heating up in Congress, and policymakers are hearing increasing calls for action from veterans’ organizations, civil rights groups, student advocates, business leaders, and researchers on both the right and the left. One vital call is for federal policy changes that would protect students from predatory and poor-performing institutions and ensure both students and taxpayers are getting a greater return on their investment in higher ed. Not surprisingly, often the loudest voices opposed to holding institutions more accountable for student outcomes actually represent those same institutions inside the Beltway. Colleges and universities and those who advocate for their interests have long held significant sway here. Yet the tide is changing, and it turns out that college administrators themselves are not just open to, but eager for, federal policy to focus more on student outcomes.

Working with Global Strategy Group, Third Way conducted interviews with 211 college administrators across the country, and contrary to past common wisdom, they see significant room for institutions (including their own) to improve. In short, they believe that federally funded colleges with poor outcomes should be held responsible and face greater sanctions than they do in current law. Looking at these numbers, it is clear that college administrators understand we need to do more to set students up for success in higher ed—and federal policy should no longer operate as a blank check to institutions that are not up to that task.

#1 College administrators agree students should be able to expect a return on their higher ed investment.

Coverage of the debate over greater accountability in higher ed often implies that college administrators disagree with the underlying premise that providing value for students means helping them graduate and be equipped to get a good job so they can pay back their loans. Yet when asked directly, only 23% of college administrators say the definition of “value” in higher education is primarily “to broaden the perspectives of students and make them better informed citizens.” While 73% say “the value of higher education is to set students up for success in their careers” or that both of those goals are equally important. A whopping 91% agree that “Students who attend higher education should be able to repay their student loans and get jobs that earn more than a high school graduate,” with 60% agreeing with that statement strongly. In fact, respondents agreed more strongly with that statement than almost any other question in the survey. Clearly, leaders at higher ed institutions know that students go to college in order to set themselves up for a successful career, and they believe their institutions should deliver on that expectation.

When asked how the system was currently performing, not surprisingly, administrators rate their own institution better than most. We asked them to grade the job that higher education institutions in the United States are doing to provide students a return on their investment: a quarter say institutions across the country are doing a “very good” job, but 39% say the same about their own institution. Overwhelmingly, they say a college degree is worth the investment and usually pays off (slightly more so for bachelor’s than associates and certificates, but those numbers were high across the board). And when looking broadly at the system, 84% say most institutions provide a high-quality education to their students, while 78% say institutions are doing a good job of training students for the careers of today and tomorrow. Yet despite these topline numbers, when you dig a bit deeper, college administrators clearly believe there is real room for improvement.

- Three-quarters say “The higher education institution I work for could do more to help set students up for success.”

- Administrators are split down the middle on whether their institution has done “an excellent job” offering “courses and training for students to be successful in the 21st century economy after graduation” or “could do a better job” on that measure (51% to 49%).

- They are also split on whether their institution “has done an excellent job of ensuring students complete their required coursework and graduate on time” or “could do a better job” on that measure (52% to 48%).

- When asked which should be a bigger focus for institutions, 58% think schools should concentrate more on improving quality over lowering costs (42%).

Leaders at higher education institutions also believe students need to be equipped with more information about how schools are performing on key measures of quality. Only 17% strongly agree that “students have all the information they need about how their money is spent by higher education institutions,” while 44% disagree with that statement. And only one in 10 strongly agree that “students have all the information they need about student outcomes at higher education institutions,” while 48% say that’s simply not the case.

#2 Higher ed leaders think students, institutions, and government all have a role in improving outcomes.

Looking at the federal outcomes data that is available, we know that our current higher education system simply isn’t delivering for students when it comes to getting those who enroll through with a quality degree that can enable them to get a good job and pay back their loans. When asked about who is responsible for that problem, college administrators thought there was plenty of blame to go around.

- 89% say “There are things higher education institutions can do to help more students graduate.” (40% agree strongly with that statement.)

- 85% say “Higher education institutions have a responsibility to ensure that most students who enroll graduate.” (Again 40% agree strongly with that statement.)

- Nearly three-quarters (73%) agree that “Many institutions spend too much time and money trying to enroll more students and not enough time on serving the ones they have.” (30% agree strongly with that statement.)

And when asked which was closer to their view, that institutions “need to keep up with the needs of the 21st Century economy and offer courses and degrees that allow students to be successful after graduation” or that students “need to keep up with the needs of the 21st Century economy and make informed choices on what institutions to attend and what classes to take to be successful after graduation,” two-thirds of college administrators pick the former. They also clearly see a role for the federal government in improving outcomes: 80% say “The federal government could do more to help make sure students succeed in higher education.” (43% strongly agree.)

To disaggregate what relative role college administrators think students, colleges, and the government should play in improving student outcomes in higher education, we asked about several specific metrics.

- When it comes to increasing graduation rates, leaders at higher education institutions believe students and colleges both have the power to improve them. On a scale of 0 to 10, colleges rank at 7.8 and students at 7.7 for their capacity to drive change in that area, while the federal government ranking is slightly lower at 6.1 (though only 24% said the federal government had no power to improve graduation rates, ranking it 4 or below).

- Looking at employment outcomes, administrators say colleges have the most power to improve them (7.5 on a 10-point scale), with students ranking next (at 7.3). Here the numbers for the federal government were slightly higher (6.5) than on graduation rates, and only 19% think it has no power in this area (4 or below).

- The responsibility index shifted slightly when it came to loan repayment. Here college administrators rank the federal government as having the most power to improve loan repayment rates (7.3), with colleges next in line (6.7). These higher education leaders rank students’ power to change loan repayment rates lower than any of the other actors we tested, including state government.

#3 Leaders at institutions believe improving federal incentives and guardrails should be top priorities.

While the advocates for institutional interests inside the Beltway often complain about overregulation and are actively pushing both the Trump Administration and Congress to deregulate, college administrators do not feel overly burdened by federal requirements. When asked about the biggest obstacles they encounter, only 24% say the most important challenge they face is “too much interference by government,” ranking second to last on the list of eight options. Overwhelmingly, the biggest challenge is “lack of financial resources” (45%), with the second being “students not prepared to do college-level work” (38%). More administrators actually say their biggest challenge is “too much focus on enrollment and not enough on student success” (30%) than “too much interference by government.”

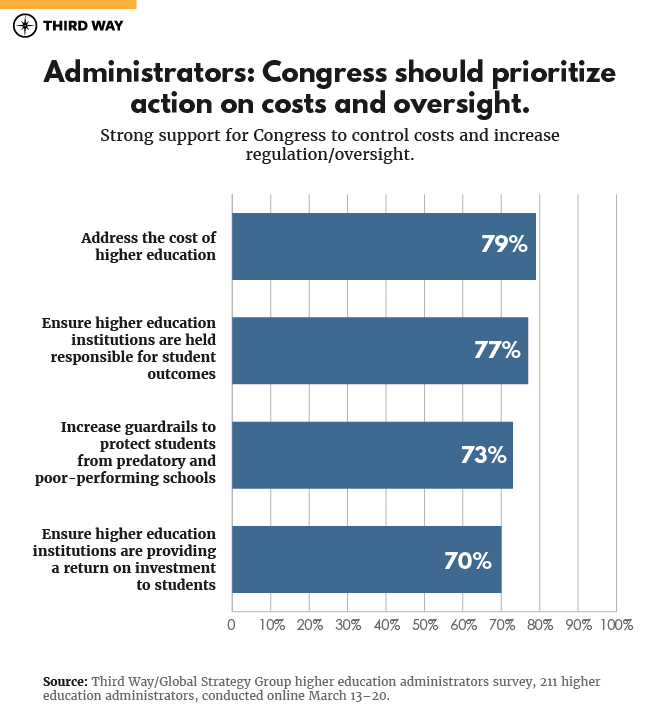

When asked an open-ended question about which areas should be the biggest focus for Congress in improving higher ed policy, 37% identify controlling costs and student loans, while another 23% say oversight and regulation—for a combined 60% indicating an active role for the federal government. A smaller proportion (34%) think the main federal role should be simply providing resources and funding (20%) or no role at all (14%). Given a list of specific priorities Congress could advance:

- 79% prioritize “Addressing the cost of higher education,” with 47% strongly urging a focus on that priority.

- 77% want Congress to focus on “Ensuring higher education institutions are held responsible for student outcomes,” with 40% saying that should be a very important priority.

- 73% prioritize “Increasing guardrails to protect students from predatory and poor-performing schools,” with 48% saying that should be a very important priority for Congress (meaning almost half of administrators ranked it a five on a five-point scale).

- And 70% believe Congress should be “Ensuring higher education institutions are providing a return on investment to students,” with 36% saying this should be a very important priority.

Given that there was such wide support for federal government action to increase institutional accountability, we then asked about what sanctions should apply to schools that don’t deliver for their students—in particular, those that receive federal money but are leaving most of their students unable to earn enough to pay back their loans.

- 59% of college administrators say those schools should be required to submit a plan for improving their student outcomes to the Department of Education.

- 57% say they should be required to disclose their student outcomes publicly.

- 44% believe those schools should face immediate review by their accreditor.

- And even among the very institutional leaders this policy would impact, 32% say those schools should lose access to federal financial aid.

- A mere eight percent of college administrators say federally funded institutions that leave most of their students unable to earn enough to pay back their loans should face no sanctions.

#4 College administrators support policies that hold institutions accountable for student outcomes.

Far from eschewing responsibility, the institutional leaders we polled were open to and sometimes eager for the federal government to put greater emphasis on improving student outcomes in higher ed.

We asked about a range of policies, and not surprisingly, three-quarters support a range of ideas unrelated to institutional accountability that are prominent in the federal higher ed conversation:

There is even substantial support among college administrators for some of the more hawkish accountability ideas under consideration—including sticks, not just carrots:

Conclusion

Though policymakers often express fear that institutional leaders will staunchly resist any attempt to make colleges take greater responsibility for the outcomes of the students they enroll, most college administrators agree that schools need to do more to ensure their students are getting a return on their investment. They also believe the federal government has a role to play in advancing that goal and should be more active in pushing institutions to deliver for their students. It turns out that higher education leaders are ready to be held more accountable for the results they produce. Policymakers should step up and use the next Higher Education Act reauthorization to heed that call. To explore the full toplines of the survey, click here.

Methodology

Global Strategy Group conducted an online survey of 211 higher education administrators nationwide from March 13-20, 2019. These higher education administrators worked across public, private, and proprietary or for-profit institutions, as well as four-year college, community college, and vocational schools. The higher education administrators job titles included: Presidents, Provosts, Chancellors, Deans, and C-Suite level executives at the institutions. The margin of error at the 95% confidence level is +/- 6.75%.

Subscribe

Get updates whenever new content is added. We'll never share your email with anyone.