America’s Got Talent—Venture Capital Needs to Find It

Takeaways

- Access to capital is critical for creative destruction and productivity increases that drive long-term growth in the economy. Venture capital (VC) is the prevailing way in which the highest potential new businesses get the equity they need to grow.

- In 2016, the VC industry invested $69.1 billion in U.S. companies, the second-highest total in the past decade. But VC does not serve most of the country, as only 22% of VC investment went to companies outside the four venture hubs of San Francisco, New York, Boston, and Los Angeles in 2015.

- Furthermore, VC does not look like America. An analysis of newly released Census data shows that of the 3,497 startups surveyed that received VC funding in 2014, just 78 were black-owned, 210 were solely Hispanic-owned, and 458 were solely female-owned.

- Most VC funding is concentrated in the tech industry, with 48% going to software companies alone in 2016.

- There are new policy approaches attempting to open up access to capital. Online crowdfunding platforms are opening opportunities to more investors. Government-backed VC efforts are increasing access in underserved states. But more efforts are needed, from both policymakers and industry leaders, to extend the virtues of VC to a wider array of promising new businesses.

Is the consolidation of VC in Silicon Valley contributing to the economic divide between a handful of booming urban economies and everywhere else?

Imagine if the University of Alabama only recruited football players from its home state. What would its team look like? Would it be the perennial national title contender that it is now? The Crimson Tide would probably still be good, but given that 56 of its 99 players come from out of state, it’s hard to imagine that the team would be so dominant.1

But of course, the University of Alabama knows better. Coach Nick Saban recruits players from all over the country. He looks everywhere from Virginia to Washington state, because he doesn’t want to miss out on the next star player.

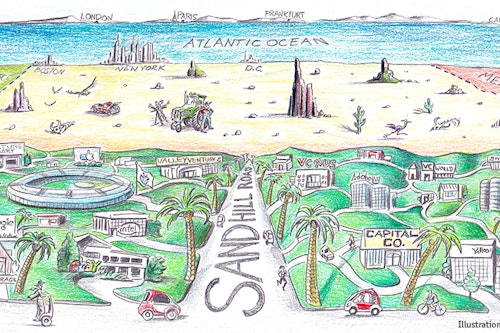

The venture capital (VC) industry could learn something from the University of Alabama about recruiting talent. Right now, the VC industry looks overwhelmingly to just four metropolitan areas for the talented entrepreneurs seeking to earn VC money and guidance. San Francisco, New York City, Boston, and Los Angeles received nearly four-fifths of VC investment in 2015, leaving just one-fifth for the rest of the country. It stands to reason that VCs are missing out on a lot of talent.

The United States is home to the world’s most ambitious entrepreneurs. These visionaries can be found in every region and every state in our country, but they need the funding, mentors, and resources to help them grow into the next big thing. The VC industry is a key accelerator for turning a great idea into a Fortune 500 company. In 2016, it poured $69.1 billion into American startups.

But the distribution of VC tells a different story. A majority of states are starved for this important source of funding. The maps below illustrate the problem by comparing the volume of VC investment to state economic output (or “state GDP”). In 2016, only the four states colored dark green had VC-to-GDP ratios above the national average of 0.4%: California (1.5%), Massachusetts (1.2%), Utah (0.8%), and New York (0.5%). The remaining 46 states and D.C. came in below average. Of those, the 27 states shown in gray received VC investment equal to or less than 0.1% of their output. To further drive home the point, Steve Case noted that 90% of VC funding went to states that voted for Hillary Clinton, while only 10% went to states that voted for Donald Trump.2

Venture Capital Density: VC Funding as a Percentage of State GDP

Source: Author’s calculation; Bureau of Economic Analysis and National Venture Capital Association data.

It wasn’t always this way. Back in 1995, the rest of the country—everywhere outside of the four major VC hub cities—got about 50% of VC funding. This begs the question: Is the regional consolidation of VC contributing to the economic divide between a handful of booming urban economies and everywhere else? It likely is, because startups are America’s best job creators. Businesses less than one year old account for 3% of employment but almost 20% of gross job creation.3 These businesses best represent creative destruction: high-risk, high-reward ventures that often transform an entire industry. And venture capital is what supports these entrepreneurs in building the next great American success story. Five of the ten biggest companies in the S&P 500 today—Apple, Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, Amazon, and Facebook—are venture-backed tech companies. According to a recent study from Stanford’s Business School, 38% of employees at public companies founded in the past 40 years have worked for companies backed by VC in their early stages.4

To find the next generation of great companies, the VC industry invests an average of $170 million in 15 startups every day.5 However, there are groups of entrepreneurs VC isn’t reaching, and they aren’t just entrepreneurs located outside of the four major hubs. Women, black, and Hispanic startup founders receive VC funding at lower rates than do male, white, and Asian founders. And tech firms are twice as likely as non-tech firms to receive venture capital funding.

The economy would be better off if the VC industry reached a wider group of investors and entrepreneurs. A more dispersed venture industry would help spread the gains of economic growth to more people and regions. This report details just how concentrated VC has become and examines why the industry is not reaching a wider variety of new businesses.

What Is Venture Capital?

As described in our previous report on access to credit, the vast majority of new businesses seek bank loans to fund their initial business expenses. This is especially true for sole proprietors and businesses seeking to remain small. For high-growth businesses, however, equity financing can be a better match for their needs. These businesses typically have an idea that has the potential to be transformative, but their products need time to develop before they become profitable. With equity, an investor offers a company an upfront amount of money in return for an ownership stake that represents his or her share of future profits.

A brand-new business typically starts by asking friends and family to invest. According to Fundable, the average contribution per investor at this stage is $23,000.6 Then, an entrepreneur may decide to seek angel investors: high-net-worth individuals who invest in startups using their personal wealth and offer advice and personal connections.7 The next step in the fundraising sequence is venture capital. VC firms raise their funding primarily from pension funds, charitable foundations, university endowments, insurance companies, corporations, and very wealthy families.8 The investors are known as limited partners, or LPs. Their contributions are pooled into a fund, which can be drawn upon to invest in companies. Startups receive funding in stages, from $1 million in the initial “seed” round to $10 million in later rounds.9 In exchange for this investment, startups not only offer their investors equity in the company, but also the opportunity for their VC investors to take a hands-on role in management decisions and to sit on the board of directors.

Annual U.S. Venture Capital Investment

In 2015, the VC industry had its biggest year since the turn of the century, with $79.3 billion invested in startups. But contrary to the large volume of venture dollars invested, the venture industry reaches a very small share of businesses. Over the last decade, an average of 6,300 U.S. companies participated in a VC deal on an annual basis.10 That’s about 0.1% of the more than 5 million active firms in the United States.11 Not all of them are successful. About 25-30% of startup businesses that receive VC investment go out of business, and up to 75% don’t produce their projected return on investment.12 One blockbuster win, however, can generate more than enough return to compensate for the investments that don’t pan out. It can generate thousands of new jobs—so even though VC money only touches a small handful of businesses directly, it has a substantial impact on job creation.

Venture capital will never be the right tool for the vast majority of businesses. But still, this extreme concentration of funding begs the question: Who is missing out on VC, and why? First, there is a significant number of startup founders who don’t have the means or connections to tap into VC. There are still others who may be able to access this capital, but they struggle to get all of the funding they need. These entrepreneurs tend to belong to three underserved groups: founders outside of Silicon Valley and other VC clusters; women, black, and Hispanic founders; and (albeit to a lesser degree) non-tech industries.

Three Venture Capital Deserts

"Your geography is not a fit for us.” —Email response from a Silicon Valley VC firm to a St. Louis-based CEO

1. Regional consolidation

The most glaring breakdown on VC funding is its geographic dispersion, or lack thereof. Nearly 80% of the investments made by VC firms in 2015 were made in just four metropolitan areas: San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and Boston. By contrast, 50% of VC money went outside of these four areas in 1995.13

Increasing Rates of Geographic Concentration in Venture Capital Investments,

1995-2015

Source: Center for Regional Economic Competitiveness and Cromwell Schmisseur, “Program Evaluation of the US Department of Treasury State Small Credit Business Initiative”, 2016, Figure 4-2

That leaves other metros clamoring for their share, because VCs are a tremendous source of growth for a local economy. Economists Rebel Cole, Douglas Cumming, and Dan Li find that a 10% increase in the number of VC firms in a metropolitan area is associated with a 2.6% increase in the number of companies with 5-19 employees, a 2.9% increase in employment at these companies, and a 3.9% increase in total payroll.14 The outsized influence VC has on economic growth makes it all the more necessary to spread the flow of VC to more metropolitan areas in the United States.

Consider one anecdote that can perfectly illustrate the effect that rapid consolidation of VC is having on the rest of the country. When Tallyfy Inc. CEO Amit Kothari, based in St. Louis, pitched his idea to several VC firms, he received responses claiming, “Your geography is not a fit for us.” In fact, according to his story in the Wall Street Journal, three advisors told him to emphasize in his pitch that his team was moving to the San Francisco Bay Area, whether or not it was even true.15

It may be that this particular firm was not the right investment for other reasons. But demanding that an entrepreneur must move to California for VC consideration is unrealistic, especially considering how expensive it is for a startup to move to the Bay Area. San Francisco has rapidly become the most expensive city in the country, with housing prices rising 11.5% in 2015 alone.16 Employees who have seen housing prices in Silicon Valley increase by 54% since 2012 are now living in their cars.17 The share of VC funding in the Bay Area has gone from 22.6% in 1995 to 46.4% in 2015. This is not a sustainable or desirable model for growth.

Startups in the Bay Area are forced to raise even more money to hire and retain employees who have a higher cost of living. Technology companies and inhabitants of Silicon Valley argue that such consolidation of talented people who can feed off of one another in a purely innovative environment is well worth the rising costs in housing and food. There’s also a business ecosystem that develops, in which startups become suppliers to—or customers of—existing large businesses. However, it may be that larger companies, not startups, benefit the most from an agglomeration of talent in the Bay Area. Because bigger firms can poach individuals from startups with enormous compensation packages, new businesses find it difficult to retain talent. VCs and startups alike lament the ever-increasing funding needed just to hire quality individuals.18 Therefore, both would be wise to consider alternative metropolitan areas to set up shop.

The fact is, smart business ideas are not exclusive to the Bay Area. They can be found in all locations regardless of whether they are large metropolitan areas or small rural areas.19 Large VC firms—those with more than $500 million in investments—are concentrated in Silicon Valley because that’s where they invest most of their money. And institutional investors tend to invest with large VC firms because they believe them to be the best judges of where to invest. It’s a vicious cycle that leads to lower levels of economic development in the rest of the country. But it doesn’t have to persist. As we discuss in the final section, policymakers and industry leaders have launched programs to address this problem.

2. Women, African-American, and Hispanic founders

Entrepreneurs and industry share the concern that women, African-Americans, and Hispanics are underrepresented in venture capital. Our analysis of the 2014 Census Survey of Entrepreneurs shows that among firms under two years old that received VC funding that year, just 2% were black-owned, 6% were solely Hispanic-owned, and 13% were solely female-owned.20 Using another metric—management rather than ownership—the Diana Project found that only 2.7% of VC-funded businesses in 2011-13 had a female CEO.21

The factors that contribute to these groups’ underrepresentation in VC are complex, starting with entrepreneurship itself. Even after controlling for income, wealth, and education, black households are 5% less likely to start a business, Hispanic households are 6.7% less likely, and female-headed households are 3.9% less likely, according to Kate Bahn, Regina Willensky, and Annie McGrew of the Center for American Progress.22 African-Americans and Hispanics also face longstanding barriers to building wealth, making it more difficult for an aspiring entrepreneur to go without a paycheck or encounter potential investors. A study by Robert Fairlie, Alicia Robb, and David T. Robinson finds that black founders start their businesses with about one-third of the capital of white founders.23 Additionally, Susan Coleman and Robb find that male entrepreneurs start out with nearly twice as much capital as women.24

Gender and Race Differences in Startup Capital

Furthermore, black-owned businesses have much lower levels of investment from non-owners. The average black-owned startup raises just $500 in outside equity in its first year, compared to $18,543 for the average white-owned business.25 This makes it harder for entrepreneurs to attract funding from angel investors and venture capital in the future, as they generally expect to see a pre-existing record of financial support.

Next, some women- and minority-owned businesses have other characteristics that make them less likely to attract VC. According to the Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, women and Hispanics are less likely than men and non-Hispanics to own firms in the information sector, and African-Americans and Hispanics are less likely than whites and non-Hispanics to own firms in professional, scientific, and technical services.26

These factors add up to lower rates of pursuing VC among women and minorities. Data from the 2014 Census Survey of Entrepreneurs shows that male startup owners are 119% more likely to have received VC financing than female startup owners. White startup owners are 18% more likely than black startup owners to have received VC, and non-Hispanic startup owners are 29% more likely than Hispanic startup owners. Although women and Hispanics receive their full VC funding request at higher rates than men and non-Hispanics, this may also indicate that they ask for less funding.27

Whether or not the VC industry itself adds to these disparities is tough to say. Lower rates of entrepreneurship, raising capital, and founding tech firms narrow the pool of minorities and women who could receive VC well before they pitch their companies. But the lack of diversity within VC firms should be a concern—especially among the investors who make funding decisions. A survey commissioned by the National Venture Capital Association found that although women make up 45% of VC firm employees, they comprise only 11% of investment partners. Just 3% of the VC workforce as a whole is black, and 4% is Hispanic.28 A 2016 survey of 581 investment partners at 72 top VC firms conducted by The Information found that only seven were African-American, and just 11 were Hispanic.29

It matters who is at the table when an entrepreneur from an underrepresented group walks into a VC firm, because research shows that investors are predisposed to exhibit a preference for similar people. A 2014 study by Paul A. Gompers, Vladimir Mukharlyamov, and Yuhai Xuan found that investors with the same ethnic, educational, or career background were more likely to participate in deals together—and this actually reduced the probability of the deal’s success because individuals with shared backgrounds tend to overlook drawbacks and even lower expectations for returns and due diligence standards.30

It behooves the VC industry to address the causes of gender and racial gaps—including unconscious bias—because of the evidence that they affect financial performance. As the venture capital firm First Round Capital discovered, its investments in companies with a female founder performed 63% better than those with all-male founding teams.31 When the startups that get venture backing are more representative of the American consumers buying the products, the venture industry is less likely to miss out on a business idea with great potential.

3. Founders in non-tech industries

Another area of concern is the distribution of VC investment across industries. According to the Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, 15% of U.S. businesses would be considered either “information” or “professional, scientific, and technical services,” but 27% of the firms that reported VC funding belonged to those two categories.32 Tech’s share of VC dollars is even more disproportionate. Last year, software firms alone received 48% of total U.S. VC investment—up from 24% in 2006. The total share of VC funding going to tech (software and hardware combined) has risen from 42% in 2006 to 51% last year.33

Percentage of U.S. VC Investment by Sector in 2016

Source: National Venture Capital Association, “Venture Monitor,” Q4 2016, p. 9.

Tech does not have a monopoly on job creation or revenue generation, but it does have a different business model than most non-tech firms. The VC investment model is based on spreading bets across 20-30 companies in the hopes that one takes off. While many fledgling apps and drugs may fail, the few that succeed tend to grow at exponential rates. Those winners provide the limited partners who invest in VC funds with exceptionally high returns—typically 20% per year. That’s a lot compared to the average stock market return of 7% and today’s bond yields under 2%.

The pressure to find the next multi-billion-dollar company leads VCs to develop “pattern matching” strategies as they consider new investments. Essentially, they identify what has worked in the past and try to find those qualities in new investment opportunities. That becomes the firm’s investment “thesis”—the one overarching thought that informs how the partners make decisions on which pitches they hear and which pitches they accept. Sometimes, this gets boiled down to simply tech. Indeed, several VC firms explicitly state that they only invest in tech companies.

Tech startups also benefit from the fact that the two industries have a high degree of personnel overlap. Many VCs are former tech entrepreneurs, like Andreessen Horowitz’s two founding partners, Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz, who worked together at Netscape, and Peter Thiel, who started Founders Fund after founding PayPal and Palantir. The startups that these and other VCs fund are often led by alumni of the tech companies at the top of the Fortune 500 list.

One way to look at this is that the tech industry is highly supportive of new entrepreneurs. Other industries have not developed such a highly formalized network of funding from mentors to mentees. On the other hand, this can make it tough for non-tech entrepreneurs to tap into VC. Pattern matching works against non-tech startups when firms have little to no history of working with their products and services. And entrepreneurs coming from other industries may have a steeper learning curve when it comes to mastering the language of VC deals compared to founders who have built their careers in the Silicon Valley ecosystem.

A tech-only thesis can be less limiting if its definition is sufficiently broad. Indeed, some startups offering products like beverages and apparel have been able to spin their e-commerce platform or product development as tech characteristics. For example, the fast-casual restaurant chain Sweetgreen leveraged its app to score a recent $95 million VC funding round.34 But the overwhelming volume of dollars flowing toward the software industry indicates that there’s more than just categorization at play. Since almost every type of business must have an online presence to survive today, there should be more businesses in non-tech sectors getting VC support.

Approaches to Opening Access

The obstacles facing the three venture capital deserts are serious but not insurmountable. Both public policy and private-sector initiatives can help close these gaps. While there has been discussion around a number of legislative and industry-led proposals, three in particular merit close attention: equity crowdfunding, the State Small Business Credit Initiative, and change from within.

1. Opening early-stage equity to more investors

Not too long ago, only a select group of institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals could gain access to early stage equity investments. That changed with the JOBS Act. Passed in 2012, the JOBS Act allowed all Americans to invest in start-ups through crowdfunding: the practice of funding a project or company by raising small amounts of money from a large number of people, typically through the Internet.

Prior to the JOBS Act, raising money this way was explicitly forbidden. The Securities Act of 1933 laid out two avenues for companies to raise equity: registering with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which could be expensive and time-consuming, or directly pursuing money from accredited investors (currently, individuals with $1 million in net worth and $200,000 in annual income) without registering. Startups have typically done the latter.35

The JOBS Act opened the market to non-accredited investors by legalizing crowdfunding. Companies can now offer up to $1 million in securities through approved online portals. Businesses raising money through crowdfunding have to comply with annual reporting requirements, disclose their business plan, and send progress updates to investors, among other requirements.36

Expectations for crowdfunding are high. Goldman Sachs called crowdfunding “potentially the most disruptive of all new models of finance.” Equity crowdfunding doubled in size from $2 billion to $4 billion over the last year, and the World Bank predicts crowdfunding will be a $96 billion-per-year market in the developing world by 2025.37Furthermore, companies looking to raise money now have another tool at their disposal—one which may prove valuable in increasing geographic and demographic diversity within the startup world. For example, 47% of the businesses on Indiegogo’s platform are founded by women entrepreneurs.38

Crowdfunding does have drawbacks for ordinary investors. An early-stage equity market is incredibly risky. Nine out of 10 companies listed on a crowdfunding portal are going to fail within five years.39 The one that succeeds may not deliver a return for years. So for ordinary investors looking to save for retirement or college for their kids, putting any more than a very small share of their wealth into crowdfunding investments is incredibly risky. That’s why it will be critical for regulators—and lawmakers—to watch the market as it develops and guard against abuses of ordinary investors.

The JOBS Act, however, stopped short of one reform that could have both reduced these risks and helped startups. Section 302b explicitly prohibits sales of securities through a crowdfunding platform by an investment company. But because it is so risky to invest in just one or even two startups, investors would benefit from the creation of investment companies, open to non-accredited investors, that could pool their capital, conduct due diligence, and invest their money in a diversified set of startups.40 It’s not hard to imagine ordinary investors benefiting from the upside risk and diversification they would get by allocating a small piece of their portfolios to a crowdfunded startups fund.

Finally, while there has been speculation that equity crowdfunding will compete with VC, it’s more likely that equity crowdfunding will complement VC by raising the profile of companies previously overlooked by the industry.41 Crowdfunding can give VC firms more information to work with before deciding to invest in a company: they can observe how successful the company is on a crowdfunding platform before deciding to invest.

2. Funding VC in underserved areas

Another way to grow VC’s reach is to develop mini-Silicon Valleys in regions across the country. Cities like Milwaukee, Salt Lake City, and Buffalo are working to build business ecosystems that support the development of local VC firms, so that entrepreneurs don’t have to leave town to get the funding they need to grow.42

To help small businesses recover from the Great Recession and address the geographic consolidation of venture capital, the Small Business Jobs Act of 2010 created the State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI). Part of SSBCI involved VC programs run by state governments that provided financing for local venture capital firms. Through SSBCI, states invest in VC firms geographically located within its own borders. It made a difference: 84% percent of SSBCI VC money went to the states that received only 20% of private sector VC money in 2014.43

Interestingly, states didn’t mandate that the VC firm invest the state’s money within the state. But that is exactly what happened because, as the consolidation of VC firms in the Bay Area demonstrates, VC funds tend to invest in startups located nearby.44 It’s much easier to have a hands-on approach with a company close by.

While the SSBCI has generated promising results, there are legitimate concerns about state governments taking such an active role in investment. Free-market advocates may be skeptical that the government could allocate capital more effectively than the private sector. From a practical standpoint too, there’s opportunity for corruption when public officials get to influence which companies get investments from taxpayer dollars. For example, audits of the SSBCI program in Indiana found that one of the VC firms receiving state money intentionally misused funds.

Even so, the experiment is worth continuing, because it doesn’t take much of an intervention to create a self-sustaining VC market in a new city. If a VC invests in a local business, and that business grows into a big corporation, then members of that corporation could split off to form their own businesses. The new businesses formed may require VC, which will draw new venture funds into the area. Then, if one of those new businesses takes off, some of its members could split off to form their own company—creating a virtuous cycle.

3. Promoting change from within

Public policy has an important role to play in addressing entrepreneurship and funding gaps, but the private sector must also step up. Pattern-matching strategies may unintentionally leave out great business ideas presented by entrepreneurs who come from Middle America, a non-tech industry, or a minority background. Therefore, VCs must actively go outside of their own networks to seek out and mentor entrepreneurs from underrepresented groups. Women and minorities need to be actively recruited for investment management positions, not just jobs in the back office. Limited partners can also make a difference by applying pressure on their investment managers at VC funds to diversify their portfolios by geography, demography, and industry.

Measuring the problem is an important first step toward improving diversity, and the VC industry has started to do just that. Setting up offices in new cities and supporting the burgeoning ecosystem of startup incubators around the country can also help. One of the top global startup incubators, TechStars, started in Boulder and includes programs in cities like Atlanta and Kansas City on its roster. TechStars has set a goal to double the number of women and underrepresented minorities in their programs over the next four years, as well as train staff on unconscious bias.45 Formalizing these plans and building in annual reviews, as TechStars has done, improves accountability and the likelihood of success.

Conclusion

New businesses are the source of nearly all of the net job creation in the economy. Equity investment is the critical driver of transformational new businesses, and ensuring it is accessible to the widest possible net of entrepreneurs will be critical to the future of the economy. Access to venture capital is an important ingredient for high-growth businesses to achieve their full potential. Although the amount of money pouring into VC funds is growing, it isn’t being allocated as widely and efficiently as it could be—resulting in the three deserts we outline in this paper. With new policy approaches and change from within, the VC industry could make a real difference for communities and populations missing out on economic growth.

Endnotes

“Alabama Crimson Tide Roster,” ESPN. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://www.espn.com/college-football/team/roster/_/id/333.

Steve Case, “Let’s invest in Middle America,” Op-ed, USA Today, January 18, 2017. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/columnists/2017/01/18/lets-invest-middle-america/96719570/.

John C. Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, Javier Miranda, “Who Creates Jobs? Small vs. Large vs. Young,” Report, NBER, August 2010, Page 29. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w16300.pdf.

Will Gornall and Ilya A. Strebulaev, “The Economic Impact of Venture Capital: Evidence from Public Companies, Report, Stanford University, November 1, 2015, Page 6, Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2681841.

Bobby Franklin, Letter to President-elect Donald Trump, December 1, 2016, National Venture Capital Association, p. 1. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://nvca.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/NVCA-Letter-to-President-Elect-Trump.pdf.

“Investor Guide,” Fundable, Chapter 6. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://www.fundable.com/learn/resources/guides/investor-guide/types-of-investors.

Josh Lerner and Antoinette Schoar, “Rise of the Angel Investor: A Challenge to Public Policy,” Third Way, NEXT Report, September 23, 2016, p. 5. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://www.thirdway.org/report/rise-of-the-angel-investor-a-challenge-to-public-policy.

Lee Hower, “Where Do Venture Capital Dollars Actually Come From? This Visual Explains,” Agile VC, Blog, October 29, 2014. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://agilevc.com/blog/2014/10/29/where-do-venture-capital-dollars-actually-come-from/.

”Venture Monitor,” National Venture Capital Association, 4Q 2016, p. 5. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://nvca.org/research/venture-monitor/.

”Venture Monitor,” National Venture Capital Association, 4Q 2016, p. 4. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://nvca.org/research/venture-monitor/.

United States, Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, “Census Business Dynamics Statistics: “Economy Wide,” Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.census.gov/ces/dataproducts/bds/data_firm.html.

Deborah Gage, “The Venture Capital Secret: 3 out of 4 Start-Ups Fail,” Wall Street Journal, September 20, 2012. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390443720204578004980476429190.

“Program Evaluation of the US Department of Treasury State Small Business Credit Initiative,” Report, Center for Regional Economic Competitiveness and Cromwell Schmisseur, October 2016, p. 62, Print.

Rebel Cole, Douglas Cumming, and Da Li, “Do banks of VCs spur small firm growth?,” Report, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 2015, p. 61, Print.

Cat Zakrzewski, “Venture Capitalists face Regional Quandary,” Wall Street Journal, November 14, 2016, Commentary & Analysis, Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.wsj.com/articles/venture-capitalists-face-regional-quandary-1479126603.

Kathryn Vasel, “San Francisco is expensive and resident are over it,” CNN, May 2, 2016, Real Estate Special Report, Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://money.cnn.com/2016/05/02/real_estate/san-francisco-residents-leaving/.

“High rents force some in Silicon Valley to live in vehicle,” PBS, August 13, 2016, Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/high-rents-force-silicon-valley-live-vehicles/.

“Tech firms shell out to hire and hoard talent,” The Economist, November 5, 2016, Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.economist.com/news/business/21709574-tech-firms-battle-hire-and-hoard-talented-employees-huge-pay-packages-silicon-valley.

United States, Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, “Accelerating Job Creation in America: The Promise of High-Impact Companies,” Report, Spencer Tracy, Corporate Research Board LLC, p. 54, July 2011, Print.

Author’s calculation. United States, Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, “New Funding Relationships Attempted,” Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, 2014. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2014/econ/ase/2014-ase-characteristics-of-businesses.html. Note: Including other groups who identify as minorities, including Asians, American Indians, and Pacific Islanders, raises the proportion of minority-owned firms with VC backing to 28%. Including equally Hispanic- and Non-Hispanic-owned firms raises the proportion of Hispanic-owned businesses to 7%. Including equally female- and male-owned firms raises the proportion of female-owned businesses to 18%.

Candida G. Brush, Patricia G. Greene, Lakshmi Balachandra, and Amy E. Davis, “Women Entrepreneurs 2014: Bridging the Gender Gap in Venture Capital,” The Diana Project, Arthur M. Blank Center for Entrepreneurship, Babson College, September 2014, p. 7. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://www.babson.edu/Academics/centers/blank-center/global-research/diana/Documents/diana-project-executive-summary-2014.pdf.

Kate Bahn, Regina Willensky, and Annie McGrew, “A Progressive Agenda for Inclusive and Diverse Entrepreneurship,” Center for American Progress, October 13, 2016, p. 2. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2016/10/13/146019/a-progressive-agenda-for-inclusive-and-diverse-entrepreneurship/.

Robert Fairlie, Alicia Robb, and David T. Robinson, “Black and White: Access to Capital among Minority-Owned Startups,” March 7, 2016, p. 38. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://people.ucsc.edu/~rfairlie/papers/rfr_v21_KFS.pdf.

Susan Coleman and Alicia Robb, “Access to Capital by High-Growth Women-Owned Businesses,” National Women’s Business Council, April 3, 2014, p. 14-15. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://www.nwbc.gov/sites/default/files/Access%20to%20Capital%20by%20High%20Growth%20Women-Owned%20Businesses%20(Robb)%20-%20Final%20Draft.pdf.

Robert Fairlie, Alicia Robb, and David T. Robinson, “Black and White: Access to Capital among Minority-Owned Startups,” March 7, 2016, p. 8. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://people.ucsc.edu/~rfairlie/papers/rfr_v21_KFS.pdf.

Author’s calculation. United States, Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, “Sector, Gender, Ethnicity, Race, Veteran Status, and Employment Size of Firm,” Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, 2014. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2014/econ/ase/allcompanytables.html.

Author’s calculation. United States, Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, “New Funding Relationships Attempted,” Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, 2014. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2014/econ/ase/2014-ase-characteristics-of-businesses.html.

“NVCA-Deloitte Human Capital Survey Report,” Deloitte University Leadership Center for Inclusion, December 15, 2016, p. 3. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://nvca.org/research/human-capital-survey/.

“Future List,” The Information, December 14, 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://www.theinformation.com/future-list.

Paul Gompers, Vladimir Mukharlyamov, and Yuhai Xuan, “The Cost of Friendship,” NBER Working Paper No. 18141, June 2012, abstract. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w18141.

“10 Year Project,” First Round Capital, July 28, 2015, Slide 3. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://10years.firstround.com/.

Author’s calculation. United States, Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, “Sector, Gender, Ethnicity, Race, Veteran Status, and Employment Size of Firm,” Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, 2014. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2014/econ/ase/allcompanytables.html.

”Venture Monitor,” National Venture Capital Association, 4Q 2016, p. 9. Accessed February 9, 2017. Available at: http://nvca.org/research/venture-monitor/.

Marli Guzzetta, “Why Even a Salad Chain Wants to Call Itself a Tech Company,” Inc. Magazine, May 2016, Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.inc.com/magazine/201605/marli-guzzetta/tech-company-definition.html?cid=sy01304

James J. Williamson, “The JOBS Act and Middle Income Investors: Why It Didn’t Go Far Enough,” Report, Yale Law Journal, 2013, p. 3, Print.

James J. Williamson, “The JOBS Act and Middle Income Investors: Why It Didn’t Go Far Enough,” Report, Yale Law Journal, 2013, p. 4, Print.

Adi Gaskell, “The Rise of Investment Crowdfunding,” Forbes, March 15, 2016, Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/adigaskell/2016/03/15/the-rise-of-investment-crowdfunding/#64a9926b6177.

Mary Emily O’Hara, “Indiegogo launches yearlong boost for women entrepreneurs,” The Daily Dot, March 8, 2016, Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.dailydot.com/debug/indiegogo-womens-entrepreneurs-initiative/.

Jeff Brown, “Startup Investing for the Little Guy,” Wall Street Journal, December 9, 2016, Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.wsj.com/articles/startup-investing-for-the-little-guy-1480907701.

James J. Williamson, “The JOBS Act and Middle Income Investors: Why It Didn’t Go Far Enough,” Report, Yale Law Journal, 2013, p. 7-9, Print.

J.J. Colao, “Steve Case: Crowdfunding Will Augment-Not Replace- Venture Capital,” Forbes, March 22, 2013, Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/jjcolao/2013/03/22/steve-case-crowdfunding-will-augment-not-replace-venture-capital/#252659bb602d.

Andrew Medal, “3 Unexpected Places That Are Actually Amazing for Startups,” Inc., February 6, 2017. Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.inc.com/andrew-medal/3-unexpected-places-that-are-actually-amazing-for-startups.html.

“Program Evaluation of the US Department of Treasury State Small Business Credit Initiative,” Report, Center for Regional Economic Competitiveness and Cromwell Schmisseur, October 2016, p. 61-66, Print.

“Program Evaluation of the US Department of Treasury State Small Business Credit Initiative,” Report, Center for Regional Economic Competitiveness and Cromwell Schmisseur, October 2016, p. 61-66, Print.

Dan Human, “Audit finds ‘intentional misuse’ of funds by Elevate Ventures,” Indianapolis Business Journal, June 19th, 2014, Accessed February 10, 2017. Available at: http://www.ibj.com/articles/48210-audit-finds-intentional-misuse-of-funds-by-elevate-ventures.

Subscribe

Get updates whenever new content is added. We'll never share your email with anyone.