Report Published December 16, 2021 · Updated January 7, 2022 · 28 minute read

Getting it Right: Design Principles for Student Loan Servicing Reform

Rajeev Darolia, Ph.D.

This policy brief is based on research supported by Arnold Ventures. The views expressed in this report are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of funders.

In May 2022, approximately 43 million student loan borrowers in the United States are scheduled to resume repayment on nearly $1.6 trillion in outstanding federal student loan debt following a nearly two-year payment pause implemented in response to the pandemic. This relief is set to expire amidst ample angst about burdens on borrowers and on the administration of the entire federal student loan program. At the center of this restart are student loan servicers, a much maligned—but also largely misunderstood—set of companies that handle many of the most critical functions related to students’ loan repayments, including account management, payment processing, and the provision of information about payment plans and solutions for distressed borrowers.

There is substantial anxiety about the challenges that resuming payments will pose to student loan borrowers, many of whom have experienced serious financial and health hardships, amplified by the exit of several prominent federal student loan servicing firms in recent months.1 However, concerns about servicer practices and efficiency have existed long before the repayment restart came into view. For example, high profile lawsuits have been brought against numerous loan servicers, including by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and state attorneys general, alleging wide-ranging unfair, abusive, and deceptive servicing practices—like providing misinformation, charging erroneous fees, hindering enrollment into certain types of repayment plans, and being unresponsive to borrower requests.2 In addition to lawsuits, consumer complaints about student loan servicing have been prominently highlighted in media reports and have been the focus of Congressional attention.3

Such dissatisfaction and political posturing have led to widespread calls for student loan servicing reform, a complex undertaking given the potentially competing goals of student loan borrowers, taxpayers, program administrators, and the national interest. There are no easy fixes—and reform will be ultimately limited if not coupled with broader focus on repairing our higher education finance system. In this report, I focus on three design principles that should be considered in reforming the student loan servicing system:

- Identify long-term goals and align short-term measures with them,

- Clarify the role of the servicer and simplify where and how borrowers get information, and

- Get the incentives right in contracts.

Much Ado About Student Loan Servicers

Borrowers interact almost exclusively with their servicers once they start repaying their federal student loans following graduation, leaving college, or dropping below half-time enrollment. Servicers maintain borrower accounts, collect payments from borrowers, and process requests for deferment, forbearance, and forgiveness. They are also expected to serve as an informational resource to help borrowers navigate complicated repayment options and solutions to difficulties repaying debt. Yet, even with this critical role servicers play in borrower repayment and education, borrowers have little to no choice in which company will service their loan. It is no exaggeration to characterize student loan servicing as one of the most critical aspects of the student loan system in the United States, yet an area that few people understand and many distrust.

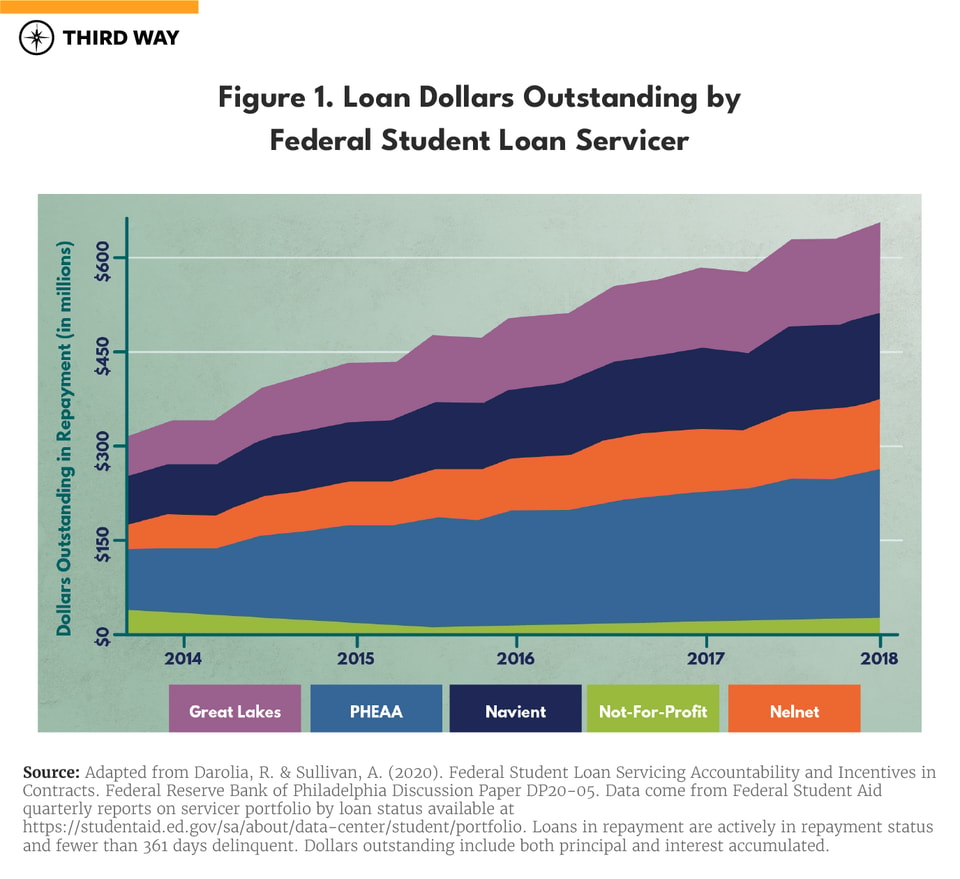

The modern incarnation of the servicer market started about a decade ago, and generally relies on the US Department of Education (Department) contracting out services to private companies, including both for-profit and non-profit entities.4 Over the past decade, the servicer market has changed dramatically, including anywhere from four to five for-profit servicers (sometimes referred to as “TIVAS” or Title IV Additional Servicers) and five to eleven not-for-profit servicers depending on the year. Figure 1 displays the loan dollars outstanding for the largest student loan servicers, with the not-for-profit servicers grouped together.

The Department itself has acknowledged limited oversight among its current contracts, publicly stating in 2020 that:

“Today’s loan servicing environment does not require maximum accountability. The legacy servicing contracts do not contain adequate incentives to reward servicers when they manage borrowers’ accounts successfully, and they do not allow for the appropriate consequences to be applied to loan servicers that fail to meet contract requirements.” 5

In the student loan context, accountability is challenging and solutions to improve outcomes are hard to produce and implement because actions and responsibilities are distributed among many parties, making it easy for any single actor to evade blame. The federal student loan system in the United States is multifaceted and multiplayer. Each actor operates within its own constraints, subject to particular incentives that may or may not serve the larger goal of promoting access to and success in higher education. And these actors face little systemic oversight to assess how their conduct reinforces or undermines that of others. Because student borrowers interact with a set of separately regulated and incentivized actors as they move into and through college and into repayment, they experience burdens at each stage that can accumulate and multiply, resulting in disadvantages that can replicate societal inequity and undercut goals of promoting socioeconomic mobility.

Servicers have become a flash point for discontent with student loans more broadly and with educational institutions. Servicers should undoubtedly be held responsible for abusive and fraudulent practices, and the Department should compel improved servicing practices and greater oversight in the future. However, much of the discontent about student loan servicing is rooted in displeasure with the federal student lending system more broadly, and even more so the system of postsecondary financial aid and pricing in the United States. Complaints about servicers to the CFPB illustrate some of this blame transference.6 For example, loan interest rates are set by the Congress, yet borrowers routinely blame servicers for these terms.

The federal student loan system in the United States is multifaceted and multiplayer. Each actor operates within its own constraints, subject to particular incentives that may or may not serve the larger goal of promoting access to and success in higher education.

A borrower remarks:

“Throughout the years, I have struggled to pay down my student loans when the interest is preventing me to do so... The interest rate is criminal - and the company is making money off the backs of students who are trying to get an education to better their lives... My disgust for this company and the federal government allowing loan servicer to take advantage of students is ever growing. The debt is crippling…Something has to be done - these companies need to be held accountable - even if it means their CEO 's have to take a break from their luxury vacations on the backs of hard-working people.”

Borrowers are also commonly upset by the perceived value of the education they received from a postsecondary institution, yet often respond with reproach toward servicers. For example, in a complaint that they “received bad information about their loan,” a borrower states:

“I feel like I learned nothing from this college other than how to spend a ton of money while getting absolutely nothing in return. I was trapped. [Servicer] keeps trying to make me pay for a student loan for a school that was shut down by fraud. They were shut down by the government…Most employers find their license laughable. And won’t even accept them or look at you. I went to college there…because they falsely told you you could graduate at this time.”

These, along with the numerous related complaints levied in the CFPB database, are legitimate complaints that deserve attention and resolution. But, without ignoring unsavory actions by servicers, it is instructive to note that servicers often get blamed for things out of their control, such as loan terms and interest rates, or the quality and value of education received.

In an effort to reform student loan servicing, the Department announced the Next Gen Federal Student Aid initiative at the end of 2017, with the intent of improving the nature of how students and their families interact with the federal student aid system. A prominent aspect of this initiative is to reform servicer practices, contracts, and relationships, with its first set of contracts announced in June 2020. In October 2021, the Department announced new, and ostensibly tougher, servicing standards along with two-year contract extensions for six servicers, including new performance standards such as how well representatives answer questions and requirements that servicers respond to complaints in a timely manner. But the path to reform has been slow and riddled with legal and regulatory challenges, including changes in priorities following the transition from the Obama to Trump Administrations, multiple cancelled solicitations, and lawsuits from private collection agencies and existing servicers. As a result, clarity on strategies and timeline for student loan servicing reform remain elusive.7

Such uncertainty has already led to major changes in the student loan servicer market. One of the largest servicing companies, the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (PHEAA), which services over eight million borrowers, announced in July 2021 that it was exiting the student loan servicing business. PHEAA also operates FedLoan Servicing, the primary administrator of the much-maligned Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program. Under PSLF, borrowers can have their loan balances forgiven after about ten years if they work for a qualifying public service employer and satisfy other requirements. However, the program has faced a deluge of borrower complaints about confusing guidelines, erroneous information, and improper denials, leading to congressional inquiries, lawsuits, and government scrutiny.8

The PHEAA announcement was followed within weeks by another major servicer, Granite State Management & Resources, announcing that it will also suspend its public student loan servicing operations for its roughly one million borrowers by the end of the year. Most recently, Navient announced in September 2021 that it too would be exiting, transitioning its responsibilities for nearly six million borrowers to another company called Maximus.

With so much at stake, and in a period of regulatory and market uncertainty, there is a critical need to reconsider the design of the student loan servicing system. The following section lays out three design principles that Congress and the Department should consider when making these changes.

Core Design Principles For Student Loan Servicing Reform

1. Identify Long-Term Goals and Align Short-Term Measures with Them

Successful loan repayment is a proper long-term goal but should not be the exclusive objective—borrowers’ long-term financial health and socioeconomic mobility should be also prioritized. Similarly, staying current on monthly repayment obligations is an important short-term measure, but so are actions that potentially improve the reliability of student loan payments, such as active engagement with an account so that the borrower has up-to-date information or participating in training that enhances borrowers’ financial literacy.

The first necessary step for student loan servicer reform is to identify the long-term goals of servicers—and, more broadly, the federal student loan system—and then properly align these long-term goals with things we can measure in the short-term. Servicers are focused on (and paid for) short-term measurable outputs like borrowers making a payment on loans on a month-to-month basis, but it is the more nebulous longer-term social welfare outcomes, like economic prosperity, health, and stability that we should care the most about. Therefore, it is important to make sure that the Department promotes and compensates for short-term outputs that align with those long-term goals.

Identifying long-term goals is a difficult and multidimensional question that starts with determining what issue student loans should be used to address. Yet part of the current problem is that there is implicit disagreement about the role of student loan servicers that derives from disagreement about the goals of our student loan system. Bringing these discussions into the foreground and being clear about what role we want servicers to play is critical.

Student Loans as a Policy Tool

There are multiple ways to think about the role of student loans as a policy tool. Higher education presents a timing problem: Students have to foot the bill for attending college before they can reasonably be expected to reap the benefits of their educational investment. Most students who go to college will directly benefit in the form of higher wages, higher probability of employment, and a host of other advantages, but many students lack access to sufficient funds before or during their education, hindering their ability to attend at all. Since it’s socially beneficial to encourage college enrollment, and because there is a limited private student loan market, this timing problem creates a need for a policy lever that can alleviate students’ credit constraints.9 Public student loan programs are well-suited to address this timing problem.

However, the current system also asks student loans to play a role for which they are not well-suited, which is to solve a social underinvestment problem where too few students—especially those who are not socioeconomically privileged and belong to minoritized racial and ethnic groups—go to college, meaning that the country will have hindered potential for a host of many other benefits that come with having highly educated and better skilled individuals including more innovation, robust economic growth, and reduced inequality.10 Loans are not the most efficient or effective solution to the social underinvestment problem; a more befitting policy solution to promote both aggregate growth in and a more equitable distribution of highly educated individuals is to invest in students by subsidizing their costs of attendance.11

The outsized role of student loans in higher education means that while improving the student loan servicing system may benefit borrowers and the public, such reform will be limited without addressing the root need to enact broad-scale reforms to our higher education finance system. We can therefore think about two general pathways for student loan servicing reform: structural changes that align student loan servicing practices with a properly designed federal financial aid structure or tweaks at the margin of student loan servicing practices that try to paper over the broader cracks in the US higher education finance system.

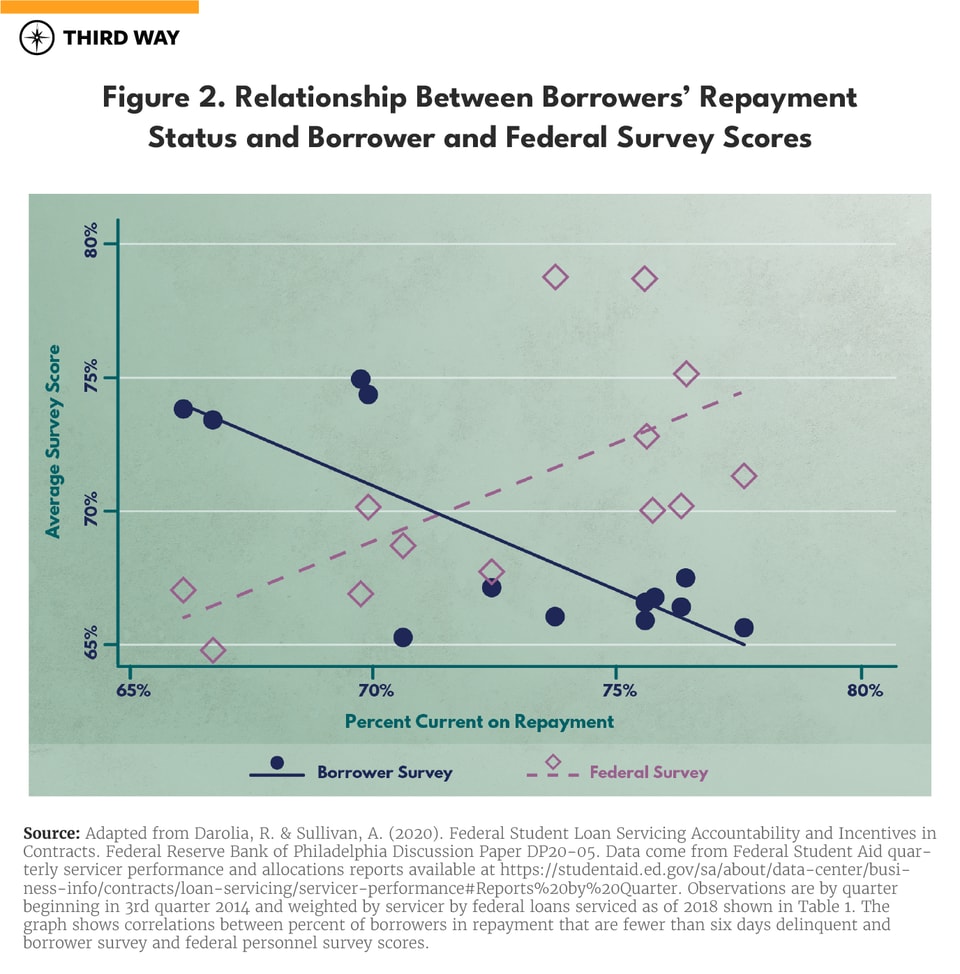

Some goals may not always be compatible with each other. For example, current performance measures for repayment and borrower satisfaction empirically conflict with each other—resulting in a situation in which, on average, servicers have lower repayment rates during periods where their borrower survey score is higher, as shown in Figure 2. This gives rise to concerns that increasing success in one area may come at the expense of the other. For example, reducing phone outreach to borrowers may lead to higher borrower satisfaction but may also reduce repayment at the margin. While it is common for public policies to have multiple goals, even if they are at times at odds, it is important to be clear about how to prioritize tradeoffs.

Successful repayment is a proper long-term goal on which servicers should focus. Loan default and delinquency can be costly to borrowers by damaging credit profiles, impeding access to or raising prices in home or auto lending markets, or leading to other penalties like professional license suspension and wage garnishment that can limit employment prospects (which, of course, is critical for repayment). In the student loan setting, there is also limited ability to expunge student loan debt in bankruptcy, further muddying the ability for borrowers to economically rebuild.12 However, if we continue the policy choice to have student loans (clumsily) try to mitigate the problem of too few students going to college than is socially optimal, then we should consider goals of the student loan system to go beyond just repayment, and incorporate other goals such as long-term financial health, socioeconomic mobility, and other measures of wellbeing. An impediment to taking these downstream and more vague goals into account is that it would be very difficult to do, both politically and administratively, and would likely result in an even more overcomplicated regulatory system than we already have.

After identifying and clarifying long-term goals, the challenge then becomes linking short-term outputs that we can observe and measure as predictors of these longer-term outcomes. Let’s take the long-term goal of successful loan repayment. Surely, short-term month-to-month repayment matters for this goal, as avoiding default or delinquency at any given time is no doubt correlated to longer-term repayment. However, there may be some actions that are not revenue-maximizing in the short term but may lead to more fruitful repayment in the long term and greater enduring financial health for the borrower. Adopting such measures necessitates being clear about the longer-term objective. Examples include lower, “rightsized” payments, matching payment amounts dynamically to ability to repay or the ability, to take a break from payments during times of hardship. Design principles inherent in programs like income-based repayment (IBR) plans or loan deferral and forbearance recognize some of these benefits, but they often come with features that borrowers do not like or do not fully understand, such as capitalized interest or longer repayment periods. And, as discussed later, the benefits are not fully translated into practice since servicers are not compensated appropriately for helping students move into these programs (and at times are arguably provided financial disincentives for doing so).

Furthermore, student loan collections enforcement is largely centered around making threats and doling out punishments, as opposed to enabling payment through programs that help borrowers understand their responsibilities, choose proper plans for their circumstances, and more broadly improve their ability to repay. Therefore, there are potential investments in structures and supports that policymakers can provide to borrowers that might lead to a stronger ability to repay in the long run, such as training and counseling that enhances borrowers’ available information and financial literacy. The idea is to invest in increasing the reliability of student loan payments in the long-run, and not solely focus on month-to-month repayment or only punitive measures to encourage compliance.13

2. Clarify the Role of the Servicer and Simplify Where and How Borrowers Get Information

Enhance clarity in the borrower-servicer relationship by consolidating servicing practices under the Department’s brand with a single front door to which students can go for information and assistance. As part of this, it is critical to simplify where and how students get information and to invest in advisors whose responsibility is to help borrowers.

Once goals are set, a next critical consideration is to clarify the role of student loan servicers. One of the reasons borrower-servicer relationships turn sour is because of a lack of trust, in part because there is ambiguity about whose interests servicers represent. As part of a lawsuit, the servicer Navient asserted that:

“Navient’s relationship with borrowers is that of an arm’s-length loan servicer, not a fiduciary counselor. A servicer’s role is to collect payments owed by borrowers. In that role, the servicer acts in the lender’s interest (here that lender is often the federal government itself), and there is no expectation that the servicer will ‘act in the interest of the consumer.’” 14

Many have cried foul about such a statement, and while this may seem objectionable to some at first blush, this is common in financial markets and among other credit products, like mortgages and credit cards, where lenders—and agents working on their behalf—foreground the interests of the lender and not the consumer.

This type of system does not work particularly well in the federal student loan context, however. Such an arrangement depends on savvy and knowledgeable borrowers who are well equipped to make decisions with far ranging and major consequences. But federal student loans are a complex financial instrument with several confusing choices that many borrowers will confront at a time when they do not have the knowledge and skills to evaluate them effectively.15 Evidence demonstrates that many students do not know how much they borrow, the terms of their loans, or their future repayment burdens, that they are unfamiliar with college financial aid and the costs and benefits of college more broadly, and that the currently required student loan counseling process is largely ineffective.16

The Department, as the lender in this transaction but also an agency working on behalf of the public, should not solely be focused on maximizing revenue and instead also promote and protect the welfare of borrowers. By extension, servicers acting in the best interest of the Department should be tasked with not just collecting payments but helping the country and students reap the benefits from their educational investments.

In addition to clarifying the role of servicers, it is important to simplify where and how borrowers get information. Given the complicated array of options and the complexity of student loans themselves, it is not surprising that students are confused and need assistance. Borrowers can also be passed from servicer to servicer as they go through different stages of repayment, sowing mistrust and making it difficult for borrowers to know where to turn for guidance. This will be especially relevant in the coming months as borrowers serviced by Navient, PHEAA, and Granite State, and potentially others as the servicing market continues to evolve, are transitioned to new servicers.

The confusion about where borrowers should turn extends beyond just repayment choices, but also in trying to understand where to even turn when problems or questions arise. In times of need, it can be confusing to the borrower whether they should reach out to their servicer, the Department, a federal government agency like the CFPB, or their school. There has been a well-intentioned proliferation of “ombudsmen” at federal, state, and institutional levels to provide additional avenues for relief and to register complaints. However, these extra layers can create even more uncertainty among borrowers as to whom they should complain and for which purposes. Such confusion will likely be amplified with a recent legal interpretation that enables states to regulate federal student loan servicers that operate in their states, likely a result of a perceived lack of accountability at a state level.17 While these actions have the potential to add another layer of protection for borrowers, they are also likely to further complicate an already convoluted system and confuse borrowers even more.18

So, what can be done? Following the intent of some of the principles set forth in Next Gen, it would be prudent to consolidate servicing practices branded under the Department’s umbrella, and to create a single “front door” to which students can go for information and assistance. It should also not be incumbent on borrowers to figure out to whom they should register complaints and from where they can appeal for relief if they are wronged. Instead, the Department, in its role both as a steward for public funds and for promoting welfare of students, needs to take responsibility for the totality of the system.19

As part of this, the Department should present information clearly and accessibly in a timely manner, encourage follow through and engagement, and employ a variety of communication mediums and strategies. A specific, meaningful improvement would be for the Department to commit to provide a timely written response for any requests made by borrowers that are not fulfilled (such as not being able to temporarily suspend payments or having payments qualify for desired programs), with clear directions on what, if anything, can be done to remediate the issue. An even more ambitious step would be to proactively reach out to borrowers to make sure they understand the implications of decisions—for example if a requested action would cause accrued interest to capitalize on their debt. While such informational initiatives are necessary, we must recognize that they will not be sufficient by themselves to solve problems associated with student loan repayment, especially if mistrust in servicers remains high.20

As such, the Department should make efforts to improve borrowers’ ability to filter and act on available information, such as through training and counseling.21 There is also potentially a role for trusted advisors whose primary focus is to serve the interests of borrowers and who (unlike servicers) are not directly compensated for collections or the repayment status of the borrower. Research indicates that more intensive counseling and attention can be more effective than nudges or low-touch interventions in helping students make decisions.22 This is a costly investment, but one that will likely not only improve student loan repayment decisions and understanding, but potentially have benefits for other types of financial decisions as well.

The Department, as the lender in this transaction but also an agency working on behalf of the public, should not solely be focused on maximizing revenue and instead also promote and protect the welfare of borrowers.

3. Get the Incentives Right in Contracts

Recognize the powerful financial incentives in contracts, including considering differential costs of servicing. Further, consider compensating not just for borrowers’ static statuses such as just “in repayment” or “delinquent” but for desirable actions like curing delinquency or meeting with a counselor, and providing premiums to better serve borrowers at heightened risk for default and who many need more attention or resources.

To ensure that borrowers feel the benefit of system-level reforms, it is essential to align incentives of those who carry out servicing actions with big picture goals. Since the Department contracts out services to private companies (and would likely continue to do so, even in a Next Gen “single front door” environment), it is critical to get the incentives right in contracts. Legal arguments in recent lawsuits make clear the need to explicitly lay out what servicers are expected to do and for what they will be paid.23 The Department wanted servicers to be a trusted advisor, but servicers saw themselves as a collection agency because that is for what they are compensated. Moreover, there are programs that provide benefits to some borrowers, such as income-based repayment plans or PSLF, that servicers fail to sufficiently market, in part because they have little financial incentive to do so.24

The Department has ways it can potentially hold servicers accountable, such as audits and compliance reports, but they are limited because it is difficult to observe servicer behavior and there are relatively minimal consequences for noncompliance. Such accountability mechanisms can also be eclipsed by the dominant financial incentives inherent in the way that servicers are compensated—with such incentives coinciding to varying degrees with the goals of the government, public, student loan borrowers, and the servicers themselves.

The Department wanted servicers to be a trusted advisor, but servicers saw themselves as a collection agency because that is for what they are compensated.

Rethinking Servicer Compensation

Consider one of the primary ways that the Department has historically compensated servicers, and resultantly, guided servicer practice. Servicers received a monthly per-borrower fee that varies by the repayment status and type of the borrower. The fee is at its maximum if the borrower is current on payments but is progressively lower as a borrower delves deeper into delinquency, in essence penalizing the servicer if the borrower is in a sub-optimal repayment status. The fee is also lower if a student’s status changes, such as if they go back to school, forbear, or defer payments. This revenue schedule should guide servicer behavior, providing incentive for servicers to help borrowers keep their accounts current and to cure repayment delinquencies. Moreover, to receive larger allocations of new borrowers to service, servicers also have the incentive to keep as many borrowers current on payments as possible.

Revenue is only part of the equation, however. What is less often considered is the differential cost of servicing borrowers with unique needs. Let’s say a borrower is behind on payments: If the cost to cure that borrower’s delinquency is higher than the revenue differential between a current and delinquent borrower, then it is not in the servicers’ financial interest to try and help that borrower become current. The problem of differential costs also relates to the expectation that servicers should help borrowers choose the appropriate repayment plan. Determining which payment plan is best for each borrower can be a complicated decision, because it can depend on expectations for future wage and career trajectories, additional educational plans, appetites for risk, and family structure, among other things. As student loan programs continue to proliferate and complexify to meet the unique and varied needs of borrowers, such variety adds cost. And part of the problem is that the administrative and paperwork requirements to change repayment plans are too onerous, causing disincentives for servicers and borrowers alike to seek these plans and causing confusion and frustration for all parties.25

Getting the incentives right in contracts to encourage desired behavior and avoid negative unintended consequences is a difficult task. Yet, if we want servicers to take the time to find the best solution for each borrower, then it is important to recognize that such tasks are time intensive and costly, and to incorporate into contracts consideration of the costs associated with servicing activities and not just the revenue associated with each borrower.

In October 2021, the Department announced ostensibly tougher performance standards, including denying new loans to servicers that do not meet those standards. The Department also announced that they will now assess servicers against goals such as borrowers’ success in reaching customer service representatives; the ways in which representatives answer borrower questions; responses to borrower requests; and more generally, the quality of customer service provided.26 While these actions have promise, especially because they are not restricted to just default and delinquency, their success will likely depend on how the Department operationalizes these goals —for example, the difficult task of defining and evaluating the “overall level of customer service provided to borrowers”—and the extent to which the operational measures used to encourage certain behavior provides financial incentive for servicers to act in desired ways.

Moreover, the Department could design contracts that do not just compensate servicers for borrowers’ static statuses—such as whether they are current or delinquent—but for dynamic transitions from one period to the next to a more desirable status. For example, servicers could receive a premium if a borrower transitions from delinquent status (behind on payments) to current on payments. Servicers could further receive a bonus when a borrower transitions to having a zero balance (successfully repays off the loan in full).27

Servicer contracts could also compensate contracted servicers to incentivize certain actions and behaviors, like encouraging borrowers to participate in strategies that may lead to better informed and more prudent student decision making, such as taking an online course about student loan topics, meeting with a counselor, or even just checking their account balance. Just as incentives matter to the servicer, incentives also should matter to borrowers. However, many of the costs of default are not salient to borrowers (for example, it is difficult to appreciate a credit score penalty) and many borrowers do not know that their wages could be garnished or professional licenses suspended upon failure to repay. It would be helpful to make penalties more salient through education and counseling, or perhaps more effectively, by providing incentives for borrowers to repay, including bonuses or rate reductions that present a clearer and more immediate benefit. This strategy is common in other financial markets like insurance markets, where successful continued repayment and good behavior is often rewarded with future reductions in premiums and other benefits. If included in contracts, savvy servicers could creatively pass through such incentives to borrowers.

Critically, there is also room to provide incentives to serve borrowers at heightened risk for default. Some of these borrowers may be more costly to service if they need more attention or resources. But if we want servicers to spend more time on “harder cases,” then the Department should compensate for this activity. We know that certain groups have greater repayment struggles on average than others (such as students who left college without a degree, racially and ethnically minoritized students, or those who face labor market barriers). The Department could pay a premium for positive outcomes, repayment status dynamics, or actions among these groups, incentivizing more attention and creativity from servicers. This action is already common in other higher education domains, such as in state performance-based funding formulas where states pay an “equity premium” for positive outcomes among targeted students.

Conclusion

Going to college continues to be a great investment for most students and for the country, typically leading to an array of individual and societal benefits. Yet to access these benefits, students must increasingly rely on loans to finance a greater portion of their education. One reason for this is that federal tuition subsidies have not kept pace with the rising prices of college.28 In the absence of available grant funds, policymakers and the public are implicitly and explicitly trying to have student loan programs solve problems they are not well-suited to address. This has also resulted in a complicated patchwork of policies that are often trying to address shortcomings in other policies, and not the root problem causes, leading to overcomplication and inefficiency. These frustrations are compounded by clear evidence that student loan burdens—including both repayment and administrative burdens—can fall disproportionately on students not already socioeconomically privileged and among minoritized racial and ethnic groups. Given this context, it’s no surprise that that student loan programs are increasingly difficult to administer, and that borrowers are upset.

In this paper, I recommend three critical design elements to consider with student loan servicing reforms: identify long-term goals and align short-term measures with them, clarify the role of the servicer and simplify where and how borrowers get information, and get the financial incentives right in contracts.

Finally, I would remiss if I did not mention the role of data in evidence-based policymaking, and the lack of data available to inform policy efforts in this context. It is critical that the Department collect standardized data from servicers on loan terms, outputs, and outcomes and make these data available to researchers within and outside of the Department (with ample security measures in place). Such data will greatly improve our ability to understand the experiences of student loan borrowers and the performance of servicers and facilitate more informed future policy progress.