Report Published February 8, 2013 · Updated October 6, 2014 · 50 minute read

Net Gains and Losses: A Modern Labor Market and a New Deal Welfare State

Eva Bertram

How do we ensure American middle class prosperity in an era of ever-intensifying globalization and technological upheaval? That is the question we are trying to answer with NEXT—a project at Third Way that taps into cutting edge research by top American academics.

What's NEXT?

Well before the Great Recession, middle class Americans questioned the ability of the public sector to adapt to the wrenching forces re-shaping society. And as we’ve begun to see a “new economic normal,” many Americans are left wondering if anyone or any institution can help them, making it imperative that both parties—but especially the self-identified party of government—re-think their 20th century orthodoxies.

With this report Third Way continues NEXT—a series of in-depth commissioned research papers that look at the economic trends that will shape policy over the coming decades. In particular, we’re bringing this deeper, more provocative academic work to bear on what we see as the central domestic policy challenge of the 21st century: how to ensure American middle class prosperity and individual success in an era of ever-intensifying globalization and technological upheaval. It’s the defining question of our time, and one that as a country we’ve yet to answer.

Each of the papers we commission over the next several years will take a deeper dive into one aspect of middle class prosperity—such as education, retirement, achievement, and the safety net. Our aim is to challenge, and ultimately change, some of the prevailing assumptions that routinely define, and often constrain, Democratic and progressive economic and social policy debates. And by doing that, we’ll be able to help push the conversation towards a new, more modern understanding of America’s middle class challenges—and spur fresh ideas for a new era.

This paper, by political scientist Eva Bertram, addresses the creation of the American social safety net. In tracing the origins of the modern social safety net, Bertram shows how the design was based on an employment market with certain distinct characteristics. Two of the biggest pieces of the American social safety net, social security and unemployment insurance, presume a “distinctive postwar model of employment relations,” one geared towards job security and stability.

Behind this policy design was an important logic, one in keeping with the values Americans place on work. As President Franklin Roosevelt said of the design of the unemployment insurance programs: “These taxes were never a problem of economics. They were politics all the way through. We put the payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their unemployment benefits. With those taxes in, no damn politician can every scrap my social security program."1

A social welfare state architecture based on participation in the labor market worked well for the first three postwar decades. Access to both unemployment insurance and to social security—the two bulwarks of the American social safety net—were dependent on participation in the labor market over a substantial period of time. But in the 1970s the job market itself began to change. People held more jobs in their lifetimes and for a shorter amount of time. “In an era of reduced job tenures and more frequent job changes, this traditional ‘base period’ for eligibility [in the unemployment compensation law] makes it more difficult for many workers to qualify for benefits,” Bertram writes.

The effects in the current recession have been dramatic, but the trend was evident long before this recession. According to Bertram, “As a result of these and other program rules, fewer than half of unemployed Americans have received unemployment benefits in most years over the past three decades.” At the end of 2008, the most severe period of this recession, only 45% of the unemployed were receiving benefits.

A second consequence of these changes in the labor market is that an increasing number of Americans are falling between the cracks in the social safety net. Ineligible for traditional unemployment insurance, they are increasingly moving to take advantage of programs such as Food Stamps and Medicaid that were originally thought of as programs for the poorest of the poor. In addition, the welfare reforms of the 1990s which worked well in a robust job market, no longer provide as much of a safety net. Like Roosevelt, President Clinton understood that linking welfare to work would strengthen the program and he was able to build bipartisan support for an increase in spending on the poor through an expansion of the EITC (Earned Income Tax Credit). This program worked well for the first decade and reduced welfare rolls but in a jobless recovery it suffers from the same weakness as the unemployment insurance program—the declining number of stable jobs at all levels.

Progressives spend a great deal of time these days defending the social safety net from harsh cuts and attacks by a right wing dominated Republican Party. But in addition to defending the idea of a social safety net it is time for Progressives to design a series of reforms that align the rules of the social safety net with the realities of a job market that is no longer as stable as the job markets of the postwar years. This is a major challenge for 21st century progressives since the link to work is one that ties the safety net to basic America values. Reforming the social safety net will require that we re-examine and rebuild the very architecture of the public sector—an architecture that must change significantly if we are going to deliver on the next America Dream.

Dr. Elaine C. Kamarck

Resident Scholar, Third Way

Jonathan Cowan

President, Third Way

—

The recent recession and slow recovery have produced economic hardships for American families on a scale not seen in generations. The downturn has exposed serious weaknesses in the U.S. labor market, trends that predated—but have been worsened by—the 2007–2009 recession. It has also tested the limits and effectiveness of the U.S. social safety net, which conditions eligibility and benefits for core programs on labor market participation and performance.

Current conditions in both employment and social provision call for a close analysis of the origins and implications of our system of work-based social protections. This paper addresses these questions in four parts. Part One briefly traces the origins of New Deal social provision and the central role of employment in the system. Part Two charts the transformation of the labor market from the early postwar decades (1945-1975) to the contemporary period (1975 to the present), highlighting major changes in employment security and mobility. Part Three describes the impact of these changes on the system of social provision and its ability to deliver adequate protections to Americans, focusing first on social insurance programs and then on public assistance programs. Finally, Part Four examines the performance of key social protections during and after the recent recession.

Part One

The New Deal Welfare State

The framework for the modern U.S. welfare state was developed in the wake of the Great Depression, during the New Deal. The 1935 Social Security Act established both social insurance programs for current and retired workers, and public assistance programs for certain categories of poor Americans. The social insurance programs were designed to insure workers against certain unavoidable risks, such as old age, illness, accident, or sudden loss of a job. Initially, these programs included Old Age Insurance (Title II) and Unemployment Insurance (Title III). Public assistance was provided through joint federal-state programs for three groups of poor Americans considered unable to support themselves through wage-earning: the elderly, under Old Age Assistance (Title I); the blind, under Aid to the Blind (Title X); and single mothers with dependent children, under Aid to Dependent Children (Title IV). Unlike social insurance, public assistance programs were “means-tested,” available only to those who could demonstrate a specified level of financial need.

In subsequent years, additional programs and benefits would be added. Social insurance would be expanded to include survivors benefits, disability insurance, and Medicare; and government subsidies were established as an incentive for employers to provide job-based health and pension benefits for employees. Public assistance would grow to include Aid to the Disabled, Supplemental Security Income, Food Stamps, Medicaid, housing assistance, and a host of smaller programs for the poor.

The New Deal system as a whole rested on the principle and promise of employment. The logic of New Deal social protections was clear. All who were able to work were to secure employment that would provide them access to job-based social insurance protections (such as unemployment insurance and social security). These programs would shield working families from unavoidable and unanticipated economic hardships, while those unable to work and financially needy could seek public assistance. For most Americans, in short, work was presumed to ensure not only economic security but also entry into a system of robust social protections. Eligibility for and benefit levels in the main social insurance programs were explicitly tied to participation and performance in the labor market: workers needed to demonstrate a record of employment and earnings over a specified period to qualify for unemployment or social security benefits, for example, and their benefit levels would be determined by formulas based on prior earnings. Core social insurance programs, moreover, would be funded by contributions from employees and employers made through payroll taxes. The link between employment and social insurance would boost incentives to work, New Dealers hoped; and the fact that the programs were financed in part by workers’ payroll contributions would ensure broad political support for maintaining the programs over time.2

But this link would also create certain vulnerabilities, a point not lost on the system’s creators. Aware of the hazards of widespread unemployment, leading advocates and architects of New Deal social provision sought to add policies providing employment guarantees through the private or public sector.3 These efforts collapsed, however, after the defeat of full employment legislation in 1946, with lasting consequences for New Deal social provision. Absent policies to ensure employment, New Deal social protections were tied (through the rules governing eligibility and benefits) to the private labor market and its ability to deliver adequate levels of stable work. With work as the point of entry to social insurance, the system now depended on market-generated employment to provide adequate protections against economic insecurity.

Part Two

The PostWar Labor Market

A close examination of postwar labor market trends reveals that for the first three postwar decades, the U.S. labor market provided precisely what the new welfare state required, and Americans benefitted from both strong employment and expanding social protections. The second three postwar decades saw the emergence of a fundamentally different and less stable labor market, however. The implications were serious not only for Americans’ employment prospects, but also for the effectiveness of the New Deal system of social provision.4

The First PostWar Labor Market (1945-1975)

In the wake of World War II, the U.S. experienced an unprecedented period of strong economic growth. Downturns were limited in depth and duration. By the 1960s, the economy was growing by more than 4.5% a year after inflation. Poverty declined significantly, dropping from an estimated 22% in 1960 to under 13% ten years later.5

The growing economy saw high levels of job creation and employment, and sustained increases not only in earnings but also in income equality as the robust growth lifted those in the lower tiers of the labor market closer to the median. Meanwhile, social insurance coverage and programs were also expanding, with the extension of social security coverage to previously excluded workers and the creation of Medicare health insurance for the elderly in 1965. These trends led to increased confidence in the idea that the nation’s social needs could be met largely through a strong economy, producing solid jobs backed by social insurance programs. Indeed, testimony by federal officials confidently projected that the need for the welfare state’s public assistance programs for the poor would decline and “wither away” as jobs and social insurance coverage expanded.6

Two defining characteristics of the postwar labor market proved essential to the effective functioning and growth of the New Deal system of social provision in these first three decades.

Steady and Secure Employment

Most notably, the expanding economy brought high levels of employment in the initial postwar period: in 1947, the unemployment rate was under 4%, close to the 3% level that would be produced by job changes and searches even in a full-employment economy. But the economy in these years was not only creating jobs at record levels. It was also producing jobs that provided security and stability over time.

The model guiding employment relations and career paths in the initial postwar years was developed in the country’s leading industrial sectors. Their approach to determining the allocation and terms of employment set the standard for much of the rest of the economy. Employment relations were managed largely through a system of “internal labor markets.” Within this system, the standard career path for an employee was to be hired for an entry level position at a company, and then move up the steps of the company’s defined “job ladders.” Added skills and responsibilities, accumulated over time, would be rewarded with increases in pay and benefits.7

The entire structure was geared toward security and stability, as employees and employers made long-term commitments to and investments in each other. In many cases, this model was advanced by labor unions seeking to secure a fair share of the nation’s economic growth for workers: the unionized automobile manufacturers, for example, set industry standards. Even leading nonunion firms such as IBM adopted this approach, however, recognizing the advantages of employee loyalty and longevity, reduced turnover, and a highly-trained workforce.8

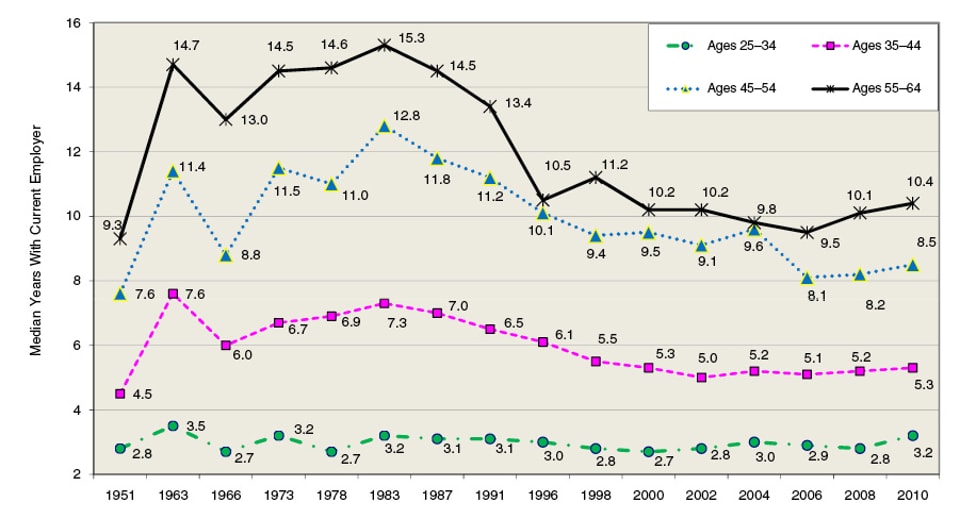

This system translated into high levels of employment security, particularly for those in the upper rungs of company hierarchies. Blue collar workers faced greater risk of layoffs, but in companies with strong internal labor markets, layoffs were often temporary measures taken in the face of severe financial pressures on the company, and workers would be rehired when business picked up.9 The broad trend toward stable employment was reflected in data on the length of time workers spent on the job: in 1963, the median time a 35 to 44 year old male worker would spend with his current employer was 7.6 years.10 Longer job tenures were common for older workers: through the 1970s, more than 60% of male workers toward the end of their careers had spent ten years or more with their current employers.11 As Figure #1 illustrates, job tenure rose for workers of all ages in the first postwar labor market, then fell sharply for most workers in the second postwar labor market.

Figure #1: Male Prime-Age (25–64) Workers Median Tenure Trends, by Age, 1951–201012

Chart Source: “ebri.org Notes,” Newsletter, Employee Benefit Research Institute, Vol. 31, No. 12, December 2012, p. 3. Accessed December 21, 2012. Available at: www.ebri.org/pdf/notespdf/EBRI_Notes_12-Dec10.Tenure-CEHCS.pdf.

Data Source: Data (for 1951, 1963, 1966, 1973, and 1978) from the Monthly Labor Review (September 1952, October 1963, January 1967, December 1974, and December 1979) and from press releases (for 1983, 1987, 1991, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, and 2010) from the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Rising Wages, Benefits, and Economic Mobility

An equally important characteristic of the first postwar labor market was the trend toward rising wages and income mobility. At the macro level, wages rose almost in tandem with the growth of the economy overall, and closely tracked increases in productivity. This reflected not only high levels of sustained economic growth, but also the distinctive postwar model of employment relations. At the industry and firm levels, the tie between rising productivity and rising wages was often explicit. Many leading companies shared the benefits of productivity increases with their workers in the form of higher wages. Some even wrote an “annual improvement factor” explicitly into their labor contracts, specifying that workers could count on improvements in their standards of living (through wage increases) in years of rising productivity.13

Across the economy, the pattern of consistent wage growth was evident. Through the entire period from 1948 to 1973, hourly wages in the private sector increased on average 2.6% a year. Wages increased steadily for all workers, including those at the bottom of the wage scale. Through the decade of the 1960s, for example, every 1% in economic growth translated into wage increases for workers in low-income families of more than $2.00 a week; this meant over $500 a year in increased family income when average annual growth topped 4.5%.14

Equally significant was the trend toward increased job-based benefits. The early postwar decades saw steady upticks in the proportion of the workforce receiving health and pension benefits on the job. This was due in part to high levels of job creation in sectors such as manufacturing, which generated jobs that were well-compensated. The trend was also due to policy changes and to decisions by organized labor to seek expanded benefit protections through collective bargaining.15

The results were striking. Some 15% of private sector workers were covered by pensions at the outset of World War II. By the time General Motors offered a plan to its workers in 1950, coverage had extended to a quarter of the private-sector workforce. Coverage continued to grow through the 1960s and 1970s, peaking in 1980 at just under half of all private sector workers (46%).16 The growth in private health insurance coverage was even more marked, and began during the war. Employers, operating under a nationwide war-time freeze on wages, increasingly offered health benefits as a way to retain or attract workers in a tight labor market. Private health insurance coverage shot up, from under 10% of the population in 1940 to over half (51%) ten years later, and the pattern continued after the war.17

The rise in health and pension benefits was also fueled by government policy actions. In 1947, Congress set the terms for job-based health and pension plans (administered jointly by employers and unions), and in 1949 the Supreme Court affirmed that these benefits were subject to collective bargaining. This spurred unions to press for such programs, and induced many employers to accept them. In 1954, Congress provided public backing for job-based benefits by exempting a company’s expenditures on employee health and retirement plans from taxation. This created an ongoing incentive for companies to expand these programs.18

A broader range of public policies helped sustain the first postwar labor market and its distinctive characteristics. These policies included macro-economic measures to ensure high levels of growth and employment. They also included investments in infrastructure, public education, and research that drove productivity growth; health and safety and other social regulations that improved the quality of jobs; government support for unionization and collective bargaining, which increased the bargaining power of workers; and social welfare measures that provided a cushion for workers in hard times. The postwar labor market was thus the product not only of favorable economic circumstances and the support of key business and labor leaders, but also of assertive government action to create the conditions needed to sustain such an employment environment.19

The Second Postwar Labor Market (1975-present)

By the mid-1970s, U.S. economic growth and productivity increases had stalled. The downturn was the consequence of a range of external factors (such as rising competitive challenges from Europe and Asia and two oil price shocks) and internal developments (including a slowdown in capital investment and a shift from the higher-productivity manufacturing sector to the lower-productivity services sector).20 Even as the sources of the persistent economic stagnation were debated, the impact on the character and conditions of employment emerged unmistakably: by the end of the decade, the U.S. labor market was defined by a new set of quite different characteristics.

Erosion of Long-term and Secure Employment

The arrival of the new postwar labor market was not signaled by high or sustained unemployment. Despite occasional spikes, the official unemployment rate remained relatively low in the second postwar labor market. Average unemployment levels edged up in the 1970s and 1980s, then declined in the mid-1990s, reaching a low of 4% in 2000. Unemployment remained above 5% annually until 2006, dipping to 4.7% on the eve of the recent recession.21 In short, the economy overall was continuing to generate jobs and most who looked were finding work. The type of jobs created, however, had changed.

One defining feature of the new labor market was the shift from long-term and stable employment to shorter-term and less predictable work. This was in part a reflection of an emerging new employment model. In the 1970s and 1980s, a wide range of U.S. employers adopted the practice of using temporary and other nonstandard workers to augment a diminished core workforce. By the mid-1980s, many began to dismantle their internal labor markets, and jettison or modify the commitment to secure employment and predictable opportunities for advancement for their full-time employees. Employers embraced a new watchword: “no long term."22 Employees were encouraged to take responsibility for their own career development and seek “boundaryless careers” outside of the hierarchical constraints—and the stability and security—of the old model of internal labor markets.23

The data on job tenure tell the story. Tenure for men of all ages declined from 1963 to 2008. The median tenure for the 35 to 44 year old male worker described above dropped from 7.6 years in 1963 to 5.2 in 2008, with most of the decrease occurring in the late 1980s and 1990s. Tenure levels for women are generally lower than for men, though they are climbing; the increase slowed after 1987.24 Across all workers, the median job tenure was 4.1 years in January 2008, although levels differ greatly by sector and age. As noted earlier, older workers report the highest tenure rates, but also the steepest declines. Workers in the service sector recorded the shortest median tenure, 2.8 years.25 Data on the number of workers in “long-term” jobs tell the same story. Over the past three decades, the percentage of workers who have held the same jobs for ten years or more has fallen. From the 1980s to the 2000s, there were major declines for men (from half of all male workers, to under 40%) and only a modest increase for women.26

These trends cannot be attributed simply to workers seeking out greener pastures: much of the decline in job stability has not been voluntary. Government reports on job displacement show that the rate of “involuntary job loss” climbed through the 1980s, including in periods of economic expansion. More recently, 8.3 million workers were displaced in the growth years preceding the recession (2005 to 2007). Even in this growth period, nearly half of the displacements (45%) were caused by a company or plant closing or moving; nearly a third (31%) were the result of positions or shifts being eliminated. The 2007 to 2009 recession subsequently saw the number of displaced workers almost double, with “insufficient work” noted as the primary cause.27

Survey data from the late 1970s to early 2000s confirm the pattern, providing a more subjective measure of workers’ sense of their own employment security. The percentage of workers who were confident their jobs were secure fell throughout the period, except for the late 1990s. Those who said it would be “very easy” to find another position with equivalent pay and benefits declined from 34% in 1989 to 24% in 2002. The evidence suggests that their assessments were largely accurate. Interviews with workers from 1981 to 2007, conducted one to three years after a job displacement, demonstrate that more than one-third were unemployed (with the exception of the late 1990s). Those who had secured employment were earning lower pay; over a quarter no longer received job-based health insurance benefits.28 Among the more than 15 million who lost their jobs between 2007 and 2009, just under half were re-employed in 2010 (the lowest re-employment rate since the survey was initiated), and a majority of the re-employed reported a reduction in earnings.29

Alongside the gradual disappearance of stable jobs, the new labor market has seen the emergence of higher levels of short-term, contingent, and nonstandard employment; this too has increased job insecurity. Over 30% of the workforce was employed in settings that were not regular full-time jobs in the mid-2000s. To be sure, some of these “nonstandard” workers were self-employed independent contractors earning a solid income, and many contingent workers report that they appreciate the flexibility of their work. In many cases, however, contingent work reflects significant disadvantages for workers. Compared to those employed in standard full-time positions, contingent workers with similar skills receive lower pay for the same work (by some 20% on average). Contingent workers are also far less likely to benefit from job-based health insurance and pension programs. Just over one in five had employer-provided health insurance in the mid-2000s; coverage for those in full-time positions was more than three times as high.30

Like shorter job tenures, contingent employment is not voluntary for many in today’s economy, particularly for part-time workers. The percentage of part-time workers climbed in the 1970s and 1980s, with most of the growth coming from an increase in involuntary part-time employment. During the recession, the number of involuntary part-timers increased dramatically, from 3% of the workforce in 2007 to 6.6% in mid-2009.31 The cumulative effect of these trends was not primarily a reduction in the availability of work, though that was the case in some years. It was instead a long-term and consistent erosion in the number of jobs that provided security and stability.

Stagnant Wages, Declining Benefits, and Diminished Mobility

A second major hallmark of the new labor market was the trend toward stagnant and declining wages and benefits. The pattern became clear by the late-1970s and continued through much of the 1990s. Even in the high growth years of the late 1990s, wage gains were not enough to make up for the declines of the previous two decades. The 2000s brought slight wage increases, most of which were erased in the recession years of 2008 and 2009. The real median income of working-age families in 2008-2009 dropped 1.3%, to a level almost $5,000 below its peak in 2000.32

Like the trends in job stability, the absence of real wage increases over time reflects a deeper shift in the labor market: reduced wages result in part from new patterns of job creation. The country lost 2.8 million manufacturing and mining jobs between 1979 and 2007, which left employment in the manufacturing sector at its lowest level in more than half a century. At the same time, the economy generated an increase of 50.4 million jobs in the service sector. This is a wide-ranging economic sector, but most of the job growth (37.2 million) has been in retail trade and services such as business, personnel, and healthcare. These two industries claimed 78% of all net new jobs over the entire period, and represent two of the three lowest-paying service industries. Meanwhile, the loss of high-wage sector jobs put downward pressure on wages. Overall, the share of the workforce in high-wage sectors (including in both government and goods-producing jobs) decreased 13.3%, while the share in the lower-paying service sector rose 11.6% from 1979 to 2007.33

The effects of this shift in job creation emerge in wage and benefit trends over time. For the past 30 years, much of the workforce has experienced sustained periods of flat or declining wages, interrupted by brief periods of wage growth. The impact of wage stagnation has fallen most heavily on those at the bottom of the wage scale. Over the period from 1979 to 2007, workers in the 20th to 40th percentile of earners experienced slight upticks in real hourly wages (of just 4 to 5% in total, over 30 years); wages for those in the bottom 10% of earners dropped by 1%. Only those in the top 40% of earners saw double-digit increases over the 30-year period.34

The data demonstrate that in the new labor market (with the exception of a few years at the end of the 1990s), most workers could not expect the wage increases their parents had seen, even if they worked hard and consistently. And employees who started out at the bottom of the wage scale could not count on moving up the income ladder significantly over their working years.35 At the same time, workers faced a reversal in the postwar trend toward expanded benefit coverage that had brought health and pension benefits to a majority of U.S. workers—and close to 70% in the case of health insurance– by the late 1970s. Thirty years later, just over half had work-based health coverage through their jobs, and approximately two-fifths had work-based pensions.36

Viewed cumulatively, the differences between the first and second labor markets of the postwar period were stark. After the mid-1970s, workers could no longer count on secure and stable work, reflected in solid job tenures; and many experienced new levels of contingency and unpredictability in employment. Broadly-shared wage increases and upward income mobility gave way to stagnant or decreasing real wages for most workers in most years. The steady rise in job-based benefits such as health and pension coverage stalled and coverage levels slipped downward. Moreover, the trends were driven by long-term changes in patterns of job creation and employment relations, persisting across economic cycles of growth and decline.

Part Three

The Welfare State in the New Labor Market

The impact of these labor market shifts on working families has been well-documented.37 But the implications for the system of social protections are less well understood. Because of the ways they are tied to employment, the reach and effectiveness of key programs have been transformed and in many cases undermined by the changing labor market. The pattern emerges in an examination of both social insurance and public assistance programs in the context of the new U.S. labor market.

Social Insurance Programs

Employment continues to provide access to the core U.S. social insurance programs (such as social security, unemployment insurance, and government-backed but employer-provided health and pension benefits)—but not just any employment. Built into the New Deal-era structure of social insurance is the presumption that workers have access to stable jobs. The development of welfare state benefits was guided by a model of long-term attachment to one employer—in other words, the employment model of the first postwar labor market.38

Longevity on the job was used as a basis for determining both eligibility and benefit levels for several welfare state programs. To begin with, workers must “earn” their access to key programs by holding a certain job for a specified period of time. Job tenure is a condition of entry for programs such as social security, unemployment insurance, and most government-subsidized, employer-provided health and pension plans. Longer job tenures are also rewarded through higher benefits in programs such as civil service retirement programs.39

The system is also set up to support and reward jobs providing steady wage increases. Social security and unemployment insurance benefits, for example, are meant to partially replace a worker’s recent or average lifetime earnings; benefits vary depending on the level of those earnings. The decision to rely on wage-based formulas to determine benefit levels assumes that jobs will deliver decent and rising earnings over a lifetime of work.

The broader social insurance system and its structure of incentives and rewards, moreover, was built on the postwar premise that rising numbers of employers would seek to provide jobs equipped with new work-based social protections. Policy decisions to establish tax breaks for employer-provided health and pension benefits embody this idea, as do policies requiring employer contributions for programs such as social security and unemployment insurance.

In the first postwar labor market, this approach to social insurance appeared both reasonable and successful. Average wages and longevity on the job were growing, and coverage expanded for social security, unemployment insurance, and employer-provided health and pension plans. In the second postwar labor market, however, this trend no longer held. Many workers whose jobs provided social protections found that these protections were less reliable or had lost value due to shifting labor market conditions. And fewer workers were able to find or hold stable jobs providing access to work-based social protections in the first place.

At an aggregate level, the stagnant wages and more frequent job changes characteristic of the second postwar labor market contributed to an erosion in the value of benefit packages for workers—in sharp contrast to the first postwar labor market. The combined value of payroll taxes (for social security, unemployment insurance, Medicare, and worker compensation insurance) and employer-provided benefits grew at a rate of more than 6% a year during the 1960s and early 1970s, and nearly 5% annually through 1979. During the 1980s,the increase slowed to under 1% annually, and during the 1990s, the value of the average benefit package dropped.40

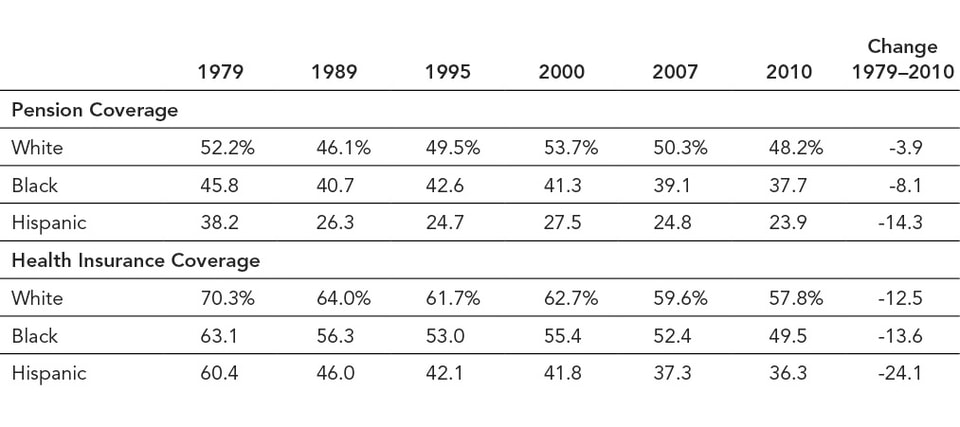

More pointedly, fewer workers received job-based health coverage of any kind. The proportion of workers covered by their own employer-provided healthcare plans dropped from 70.3% to 57.8% for whites between 1979 and 2010. The declines in coverage for black and Hispanic workers were even steeper (See Table #1). Most high-income workers (76.9%) continued to receive health insurance coverage through their employers. But for the other 80% of workers, the rate of coverage had always been lower and then dropped more sharply after the 1970s.41

Table #1: Employer-provided health insurance and pension coverage, by race and ethnicity, 1979-201042

Note: Data are for private-sector wage and salary workers age 18–64 who worked at least 20 hours per week and 26 weeks per year.

Chart Source: Mishel, Lawrence, Josh Bivens, Elise Gould, and Heidi Shierholz, “The State of Working America, 12th Edition,” Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, Table 1.4, 2012. Chart available online at: http://stateofworkingamerica.org/chart/swa-introduction-table-1-4-employer-health/.

A similar problem emerged with pension coverage. Shorter job tenures posed new challenges for workers seeking the security of job-based retirement benefits. It is common for employers to require that workers remain at a firm for five years to be fully vested in a traditional pension, for example. Yet, as Figure #1 illustrates, by the first decade of the 21st century, median tenure was declining for all but the youngest age groups, making it more likely that an increasing number of Americans would not have the job tenure needed to qualify for a pension.

In addition, fewer jobs were providing pension coverage. In 1979, more than half of all white workers had pensions; by 2010 fewer than half of all white workers were in jobs covered by pensions. As Table #1 indicates, the loss of pension coverage was even more severe for blacks and Hispanics over this period of time.

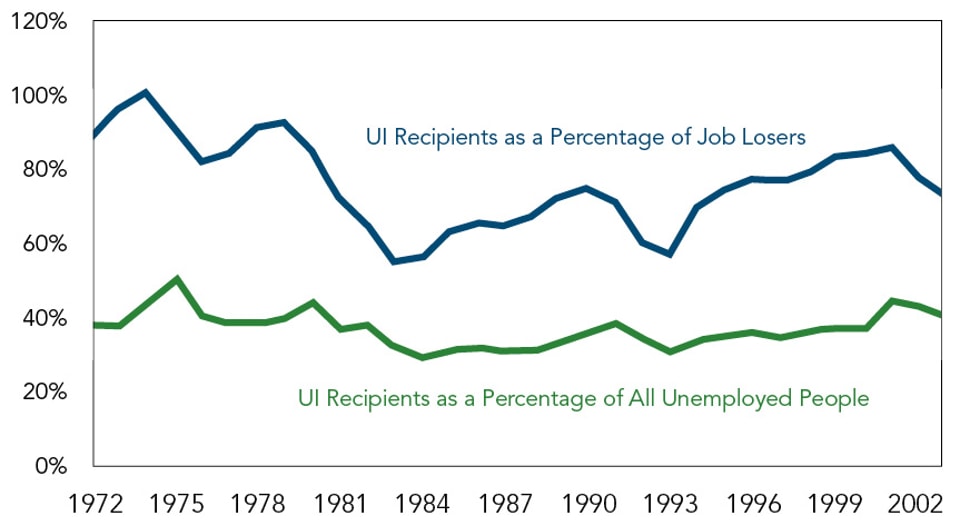

The case of unemployment insurance is a particularly troubling example of the trend toward inadequate social protections in the new labor market, with implications for a large percentage of the workforce. The program was designed to tide families over in hard times by providing a partial replacement of wages lost during periods of temporary joblessness.43 Over 95% of wage and salary workers are technically covered by the program. But beginning in the mid-1970s, the share of unemployed workers actually receiving unemployment benefits from either state or federal sources has declined, from a high point of 75% in 1975 to a low point of 32% in 1987 and 1988. As Figure #2 illustrates, in most subsequent years, the percentage of unemployed Americans actually receiving benefits through regular state programs has hovered under the 40% level.44

Figure #2: Unemployment Insurance Recipients as a Percentage of Job Losers and All Unemployed People45

Chart Source: Congress of the United Sates Congressional Budget Office, “Family Income of Unemployment Insurance Recipients,” March 2004, p. 9. Accessed December 21, 2012. Available at: http://cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/51xx/doc5144/03-03-unemploymentinsurance.pdf.

Data Source: United States Government Printing Office, “Economic Report of the President: Transmitted to the Congress February 2004,” Report, 2004, pp. 336-337. Accessed December 21, 2012. Available at: www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/ERP-2004/pdf/ERP-2004.pdf.

Several characteristics of the New Deal-era unemployment program have undermined its effectiveness in the new labor market. One problem arises from the fact that unemployment spells are longer in the second postwar labor market.46 As a result, more jobless workers in the current labor market exhaust the benefits provided under regular state programs (usually 26 weeks of coverage) before finding new work, often even when their states qualify for extended benefits.47

In addition, changes in the composition of the labor force and the growth in nonstandard employment since the 1970s have left millions of workers with inadequate coverage under traditional unemployment insurance rules. These include low-wage, part-time, and temporary employees, and a rising share of women workers.48 At issue in many cases are state eligibility requirements. State rules traditionally specify that a worker must demonstrate steady employment and sufficient income over a twelve-month period to establish eligibility, but this cannot include work and wages in the most recent three to six months. In an era of reduced job tenures and more frequent job changes, this traditional “base period” for eligibility makes it more difficult for many workers to qualify for benefits.49

Other workers face different challenges in qualifying for unemployment insurance under traditional rules. Part-time workers can face difficulties in meeting earnings requirements for the program, due to both fewer hours worked and lower hourly pay than their full-time counterparts. They can also be disqualified by state rules that require a worker to be seeking and available for full-time work in order to receive unemployment insurance benefits. This is a particular problem for women, who make up approximately two-thirds of part-time workers.50 Women workers and those in nonstandard jobs (which offer fewer sick leave and health benefits) have also been particularly disadvantaged by rules that disqualify workers from receiving unemployment benefits if they leave a job in order to attend to family medical emergencies. As a result of these and other program rules, fewer than half of unemployed Americans have received unemployment benefits in most years over the past three decades.51

Public Assistance Programs

In the wake of these changes in employment conditions and social insurance, public assistance has assumed a new role for a growing population of working families. The reach and significance of means-tested assistance has shifted in the second postwar labor market: rather than serving primarily as a last-resort lifeline for a largely nonworking population of very poor families, this assistance increasingly has served as a stopgap for working families (poor and nonpoor) who lack basic income security in the current labor market. This has provided a source of immediate aid for many families facing economic hardship. But it has also imposed a strain on many means-tested programs and created new vulnerabilities for families receiving assistance.

The changing role of means-tested assistance reflects public policy shifts as well as new levels of need among working Americans. The public assistance programs of the welfare state were originally designed for those outside of the workforce. Limited cash aid was provided to certain categories of poor Americans who were considered unable to support themselves through wages, due to age, disability or (in the case of single mothers with young children) caregiving obligations. Through the early 1970s, the vast majority of income support for the poor reflected these criteria.52

By the 1970s, however, a series of public policy changes had begun to transform the purposes and target recipients of federal income assistance for the poor. Two related policy shifts tied public assistance more tightly to employment, so that today, most means-tested cash assistance is tied to participation in the labor market.53 First, work requirements were introduced, particularly in the core New Deal public assistance program for poor families, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), later replaced with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Second, new programs and provisions were created to provide both cash and in-kind assistance to low-income workers and their families. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), though not a traditional public assistance program, was established in 1975 as a refundable tax credit to supplement the wages of low earners, and was expanded repeatedly in subsequent decades. Likewise, Medicaid’s scope was broadened to cover more low-income workers in the 1990s.54

In the context of the new U.S. labor market, the growing link between means-tested aid and employment merits closer attention. Several trends have emerged that reveal both the expanded reach of public assistance and the dilemmas this poses.

First, means-tested assistance for working families (both poor and nonpoor) has increased rapidly, in part to compensate for inadequate or irregular wages and the shortcomings of social insurance in the second postwar labor market. In less than ten years (from the mid-1980s to mid-1990s), for example, federal expenditures on programs aiding low-income workers climbed nearly tenfold, approaching $50 billion. Roughly half of this increase was driven by the growth of EITC; expansions of Medicaid were the second largest contributor.55

By design, these means-tested programs concentrate aid among low-income families. Yet increasingly, they serve as a safety net for workers higher on the income scale as well. Though still means-tested, eligibility for many programs extends well above the poverty level to address the economic insecurities of working families. The largest share of EITC benefits, for example, goes to families with annual earnings just above or below the poverty threshold ($15,500 for a single parent and child; $22,800 for a family with two adults and two children), and the program lifts 6 million a year above the poverty line. Though the credit tapers off above the $25,000 range, EITC offers a wage supplement to some families earning over $50,000 (depending on family size); indeed, the top income limit is above the U.S. median family income.56

Shifts in the targets and levels of means-tested assistance, in short, have quietly transformed such programs into a vital line of defense for many working Americans, particularly those living in the precarious region just above or below the poverty line. Their numbers are disturbingly high. All told, 100.5 million Americans (about one in three) were poor or near-poor in 2010, according to new measures developed by the Census Bureau. This included 51 million Americans with incomes above the poverty level, but by less than 50%, according to the Bureau. It is these near-poor families (some one in six Americans) who are often a single medical emergency or jobless spell away from slipping into poverty.57

Despite their extensive numbers, this group has in many ways slipped through the traditional safety net of the U.S. system of social protections. Since the New Deal, the U.S. system has channeled support along two tracks, providing social insurance to protect middle class workers and public assistance to aid the nonworking poor. There has been little focus on those who fall between the two tracks—working families who are above the poverty line but not securely in the middle class.58 Families in these circumstances have increasingly turned to means-tested aid when work and social insurance fail to meet basic needs. They have sought not only income supplements such as EITC, but also in-kind assistance in large numbers. In 2009, for example, over 45 million Americans with incomes above the poverty line drew support from at least one of the major public assistance programs (not including EITC).59

In many cases, aid programs originally intended for nonworking families have been stretched to accommodate those who are working but unable to make ends meet. Food stamps and Medicaid, for example, were traditionally limited to nonworking families enrolled in other aid programs, such as Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or AFDC/TANF.60 By 2010, nearly one in three families receiving food stamps included a working adult, a 50% increase over two decades. The food stamp program (now called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP) provided benefits to some 6 million Americans a month with incomes over the poverty line in 2010.61 Likewise, changes in eligibility rules significantly expanded the number of families with working adults who benefit from Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Although eligibility rules vary by state, coverage for children is generally available under Medicaid or CHIP for families with incomes up to $44,000 a year for a family of four. In well over half the states, the upper income limit is over $50,000 (above the median income level); in 20 states, it exceeds $65,000.62 Not surprisingly, reliance on Medicaid by working families has increased as work-based health coverage has declined. In 2009, more than 22 million Americans above the poverty line participated in the Medicaid program.63

As aid has expanded to working families, a second trend has emerged. The growing link between means-tested assistance and employment has created new vulnerabilities for many middle and low-income families. The problem arises not with programs that have grown to assist workers as well as nonworkers (such as Medicaid), but with those programs in which access is conditioned on employment (such as EITC). In the context of the post-1970s labor market—in which work is less reliable and stable—tying aid to current employment has posed distinct risks. This is particularly true in the low-wage sector: whether measured in declining wages, benefits, or security, low-wage jobs lost ground more quickly and severely than other jobs in the second postwar labor market.64

The increasing reliance on EITC as a family income supplement, for example, has left many families in a vulnerable position. For all EITC recipients, a decline in income (due to reductions in working hours or hourly wages), will bring a corresponding decline in the total resources received from wages and EITC benefits. The situation is even more dire for EITC recipients who lose their jobs, as millions have during economic downturns. At the point when they are most in need of assistance, their EITC benefits are eliminated entirely.65

A third and related trend has been a change in the composition of means-tested resources available to needy families. Most notably, a marked shift in family resources was evident from the early 1990s to the mid-2000s, away from AFDC/TANF and food assistance and toward EITC and earnings. The impact on families has ranged widely.

For the poorest families with children (those under 50% of the poverty line), total resources available fell by some 20% (from $1,033 to $825 a month) from 1990 to 2004, as the loss of more than $250 a month in traditional public assistance benefits was only partially offset by increases in earnings.66 This meant that even in a period that includes the years of strong economic growth in the late 1990s, the poorest families were worse off under the new system of increased work expectations and supports combined with reduced traditional assistance.

For a broader range of low-income families with children (those in the lowest 20% of earners), the experience was more mixed. These families did markedly better under the new system during the economic growth years of the 1990s. Their earnings and total income rose by over 50% between 1991 and 2000. Yet the rising share of income from earnings and EITC (both of which are tied to the state of the labor market), combined with the reduction in AFDC/TANF (which saw cutbacks in these years), left them more exposed to economic downturns. When the economy weakened in 2000 and then entered a period of slow recovery, earnings for the lowest quintile fell by 16% and overall income fell by 11% between 2000 and 2005, even before the recession of the late 2000s.67

On the eve of the 2007-2009 recession, therefore, the economic situation of many Americans was precarious. The terms and conditions of employment in the post-1970s labor market had produced declining access to the full range of job-related social protections developed during and after the New Deal. Changes in means-tested programs provided basic support to some working families, including millions with incomes above the poverty line, but also created new vulnerabilities when these families faced a loss of income or employment.

The Welfare State in the Recession

The structural shifts in the labor market described above pose a fundamental and continuing challenge to the overall effectiveness of the U.S. system of social provision. Yet it is also important to assess how the welfare state has responded to cyclical shifts in the labor market; it was designed in part to shield recipients from the worst effects of economic downturns.

From late 2007 to 2009, the nation faced the most sustained period of severe job loss and economic hardship since the Depression. In 2009, more than 70 million Americans—nearly one-quarter of the population—experienced poverty for at least two months during the year.68 By 2010, the poverty rate climbed to 15.1%, and the number of people in deep poverty rose to more than 20 million Americans.69 Many more faced serious economic insecurity, hovering just above the poverty line.70 More broadly, the downturn has erased 20 years’ worth of wealth accumulation for the median American family.71

How did our system of social protections perform during this downturn? And how has it done during the long period of high unemployment since the recovery began three years ago? The evidence to date suggests two answers to these questions.

First, the effects of the recession would have been much more severe and widespread without the safety net provided by the broad array of social protections.72 Without government income assistance, the poverty rate in 2010 would have been nearly twice as high as it was—28.6% rather than 15.1%. More than one in four Americans would have been living below the poverty line.73 Of the millions of Americans kept out of poverty by government assistance, most were seniors relying on social security benefits. Another 13.3 million were lifted above the poverty line by unemployment insurance, EITC, food stamps, and other programs. And 7.5 million were kept out of poverty by temporary program expansions and the Making Work Pay tax credit, passed by the Obama Administration in 2009 (as part of the stimulus package) and in 2010.74

The second and more troubling answer to the question, however, is that the safety net’s effectiveness has been uneven. The economic situation of many Americans today remains dire, more than three years after the recession formally ended; and this is in part due to the inadequacies of certain social protections. Assessing this mixed performance, both the strengths and the weaknesses, is essential for drawing lessons for policy reform. An examination of the record thus far suggests a few preliminary conclusions.

On balance, programs appeared to be better able to respond to the effects of the recession when their eligibility criteria were more standardized than discretionary, and when their financing was largely federal. These characteristics offered distinct advantages, including the capacity for a quick expansion of assistance during the downturn, and the effective delivery of those additional resources to a high percentage of eligible individuals and families. Federal funding streams proved particularly advantageous at a time when many state-led and -financed programs faced severe cuts due to state budget crises.75 In addition, programs tended to be better positioned to meet needs during a period of high and sustained unemployment when their link to work was not direct or determinative (as with food stamps, which is available to both working and nonworking families in need) or was less proximate (as with social security, which bases benefits on an extensive record of past employment).76

Social Insurance

Of the two core social insurance programs, one performed extremely well and the other less well. The social security program has proven to be an essential bulwark during the recent downturn. The program is not targeted to aid the poor, yet its impact on poverty is dramatic. Some 20 million Americans were kept out of poverty by social security benefits in 2010.77 The contrast with nonseniors is illustrative: in 2009, as the recession ended and recovery began, the poverty rate for working-age Americans (age 18 to 64) was 12.9%, a record high for this cohort. The same year, after increases in social security payments, poverty among those over 65 was 8.9%– also a record, but in this case a record low.78

At the same time, there are some reasons for concern about the demands placed on social security by the downturn. Recent reports suggest, for example, that it is being used as wage replacement by some older adults facing long-term jobless spells. Evidence suggests that hundreds of thousands of Americans are taking their social security benefits early (at age 62 rather than at full retirement age) because they cannot find work. The price of doing so is severe—an estimated loss of 20 to 30% of the value of benefits every month for the remainder of their lives.79

Unemployment insurance has also been a vital source of support during the downturn, expanding to address increased need. Federal and state spending on unemployment insurance grew from $33 billion in 2007 to a peak of $159 billion in fiscal 2010.80 That year, the program and its temporary expansions kept 4.5 million workers out of poverty.81 But there have been major (if unsurprising) limitations to the program’s effectiveness during the downturn. Because of how the program was designed and is administered in many states, fewer than half of the unemployed received benefits.82 At the end of 2008, the worst year of job losses in a generation, only 45% of the unemployed were receiving benefits, due in large measure to the fact that many state programs had not been modernized to reflect the changing character of employment in the post-1970s labor market.83 The 2009 stimulus legislation offered states incentives to modernize their unemployment insurance programs, and more than 100 state-level reforms have been undertaken by nearly 40 states, with promising but still modest results.84

Other social insurance programs saw the continuation of the broad trends of the second postwar labor market during the recession and slow recovery. Employer-provided health and pension benefits continued the pattern of decline. The overall percentage of workers under 65 covered by work-based health insurance was 68% in 2000; by 2009 it had dropped to 58.9%.85 In 2010 (as in 2009), the percentage of uninsured was at record levels. The decline was due mostly to the erosion of work-based coverage, which reached a record low in 2010. Among children, the expansion of government-provided health insurance more than compensated for the loss in employer-based coverage, but this was not the case for adults.86 Pension coverage also continued to decline through the 2000s, and stood at 42.6% in 2009.87

Public Assistance

The effectiveness of public assistance programs—like social insurance programs—has varied during and after the recession. Some grew quickly and dramatically in response to rising hardship; other programs saw a more delayed or limited response, depending in part on their structures of eligibility, benefits and funding.

One of the most effective public assistance programs in the downturn has been the federal food assistance program, SNAP. The program responded quickly to rising levels of need. From 2007 to 2011, the average number of Americans using food stamps monthly climbed from about 26 million to more than 44 million, or roughly one in every eight Americans.88 The program kept 4.4 million out of poverty in 2010.89 It is in fact the sole reported source of support for a growing number of poor Americans.90

One of the less effective public assistance programs has been the TANF program that replaced AFDC. Unlike AFDC, which expanded to meet need during recessions, TANF is a capped block grant that reserves for the states the authority to determine how many needy families will receive aid. In the wake of the recession, TANF has been one of the least responsive safety net programs, particularly as states have made cutbacks. Despite rising need, TANF caseloads hit an historic low in mid-2008, the year the bottom fell out of the labor market. Nationally, TANF caseloads declined by about 58% from 1995 to 2010, from 4.7 million to 2 million. During the same period, the number of families in poverty increased by 17%, from 6.2 to 7.3 million. Overall, there has been a severe drop in the percentage of poor families with children who actually receive TANF cash assistance. Some 68% of those families received aid in 1996; by 2010 the number had dropped to 27%, despite new increases in poverty rates during the recession.91

The Earned Income Tax Credit has provided needed assistance in recent years, including for some families unable to access adequate aid from TANF. As in previous recessions, EITC was slow to respond when the downturn hit. During 2008 and 2009, the number of EITC recipients rose by 1.2 million, while 6.3 million Americans were added to the ranks of the poor. After the recession, the program grew at a more vigorous rate, and in 2010 lifted over 6 million Americans out of poverty.92

Further evidence will be needed to provide a full and accurate picture of the performance of the U.S. social safety net during and after the recent recession. The record to date, however, reveals both the significant contributions and the continuing limitations of existing programs in addressing the nation’s social needs.

Conclusion

The United States faces formidable challenges in charting a path to economic security for American families in the wake of the Great Recession. Doing so will require asking and answering anew basic questions about our nation’s social contract—including what Americans can and should expect from work, from social provision, and from the policies that link them. Debate over these questions, among policymakers and the public, should be informed by lessons drawn from our past and present experiences with our system of work-based social protections.

This analysis of the New Deal welfare state in the context of the new labor market points to five broad conclusions. First, the New Deal welfare state not only tied the most generous social insurance programs to employment, but presumed the continued existence of an employment model with certain defining characteristics—namely, security and mobility. In many cases, rules governing eligibility and benefits presumed long-term attachment and rising earnings and mobility. Second, many programs of the welfare state arguably work best in the context of a labor market defined by these characteristics, as was the case in the first postwar labor market. They work less well in the context of a labor market marked by greater job shifting and insecurity, stagnant wages and benefits and diminished mobility—as in the second postwar labor market—even though the need for certain social protections rises under these conditions. Third, as policy reforms have tied several means-tested programs for the poor and near-poor more tightly to work, some working families have become eligible for new sources of aid. At the same time, conditions in the low-wage sector have grown more precarious, making employment a less reliable exit out of poverty and traditional forms of assistance. Fourth, the recent recession and slow recovery have exposed the strengths of some programs (such as social security and food stamps) and the weakness of others (such as unemployment insurance and TANF). The weaknesses are in part a reflection of a tension between program rules or expectations and employment conditions in the post-1970s labor market, many of which pre-dated but have been exacerbated by the downturn. Finally, this analysis suggests that a renewed commitment to adequate economic security through the welfare state will require both new and increased forms of assistance that are not conditioned on work in an uncertain labor market, and new interventions to shore up and strengthen employment in ways that reduce the risks and uncertainties of employment in today’s labor market.

About the Author

Eva Bertram is an Associate Professor of Politics at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Bertram studies American political development and public policy; areas of focus include social policy and the welfare state, and the changing character of work and labor markets in the United States.

Bertram’s most recent book project (with the University of Pennsylvania Press) examines the political and institutional sources of the transformation in public assistance policy, from the entitlement-based system of the New Deal era to the contemporary work-conditioned safety net. Building the Workfare State: The New Politics of Public Assistance traces this shift to a split and struggle within the Democratic party over the means and ends of federal income assistance for poor families, and considers the impact of the rise of work-based social policies in an economy that provides diminishing job security and stability.

A second area of research focuses on the politics of unemployment and underemployment in the United States. Bertram’s research explores what has been called the “no man’s land” between joblessness and secure employment in the current labor market, comprised in part of a growing segment of involuntary part-time and marginally-attached workers. Her interest is in the political debates and decisions that assign or displace responsibility for the rising problems of un- and underemployment.

Bertram’s first book examined the interaction between policy, politics and markets in the development of U.S. drug control policy. Drug War Politics: The Price of Denial, a coauthored project, addressed the pattern of failure followed by escalation in the U.S. war on drugs. It explored the persistence of a failed policy by examining the role of entrenched public ideas, institutional interests, and political conflict in the historical development of U.S. drug control.