Report Published October 18, 2017 · 15 minute read

One Grant, One Loan: What Exactly Does It Mean?

Wesley Whistle & Tamara Hiler

Getting an admissions letter to attend college can be one of the most rewarding and exciting moments of a person’s life. But what follows that “Congratulations, you’ve been accepted to…” statement is often a confusing and overwhelming explanation of how much that postsecondary experience will cost. Luckily, the sticker shock most students and families might experience initially can be mitigated with the help of their financial aid award letter—which identifies the federal, state, and institutional aid available to help finance tuition and other costs of attending college. And while having a menu of financing options available is an asset to the over 20 million students who attend certificate-granting, two-year, and four-year institutions, the financial aid system itself can be a complex maze for students figuring out how to successfully pay for their education each year.1

Screenshot of a Typical Financial Aid Award Letter2

That is why policymakers on both sides of the aisle have advocated for simplifying the student financial aid system. This includes legislation introduced last Congress to streamline financial aid, as well as comments made by House Education and Workforce Chairwoman Virginia Foxx (R-NC) earlier this year to create a “one grant, one loan” system as part of an upcoming reauthorization of the Higher Education Act (HEA).3 There appears to be wide agreement that simplification of the financial aid system is necessary to make the process of financing college easier for students and their families—especially for first-generation students who are navigating this process for the first time. However, some advocates worry that a one-size-fits-all approach may fail to target the students and families who need the most help. This memo offers a brief explanation of the current financial aid system and what a “one grant, one loan” system could look like. We also explain some of the concerns raised by opponents of a “one grant, one loan” approach and the responses of those who support it.

Today’s Federal Financial Aid Landscape

The history of the current federal financial aid system first began in 1944 with the passage of the G.I. Bill.4 Designed to allow veterans to more readily access a college education and workforce development programs following World War II, the G.I. Bill increased higher education enrollment from 1.15 million students to 2.45 million between 1944 and 1954—making it clear that opening the doors to financial assistance was an important way to increase postsecondary access.5 Following this model, the Higher Education Act (HEA) of 1965 expanded benefits to the general population, creating the foundation for the federal financial aid system we have today.6 Since 1965, both higher education enrollment and costs have increased substantially. Today, over 20 million students are enrolled in higher education programs, with tuition and fees averaging around $11,865 per year.7 With a larger share of Americans attending college and the increasing necessity of an education beyond high school, the need for financial assistance is greater than ever. That’s why the federal government provides a menu of financial aid options to help students both access and complete postsecondary degrees today. And while it should be noted that students also have access to state and institutional aid, this memo focuses only on grants and loans from the federal government.

Current Grant, Loan, and Work Study Options

The federal government primarily offers students two options for financing higher education: grants and loans. Unlike loans, grants do not have to be repaid, and they are typically need-based as a way to directly assist low- and moderate-income students. Loans, on the other hand, allow all students to borrow money that will be repaid (with interest) after students leave or graduate from college. Within both of these are campus-based aid programs that distribute funds to colleges and universities who then distribute the aid to students.

Grants

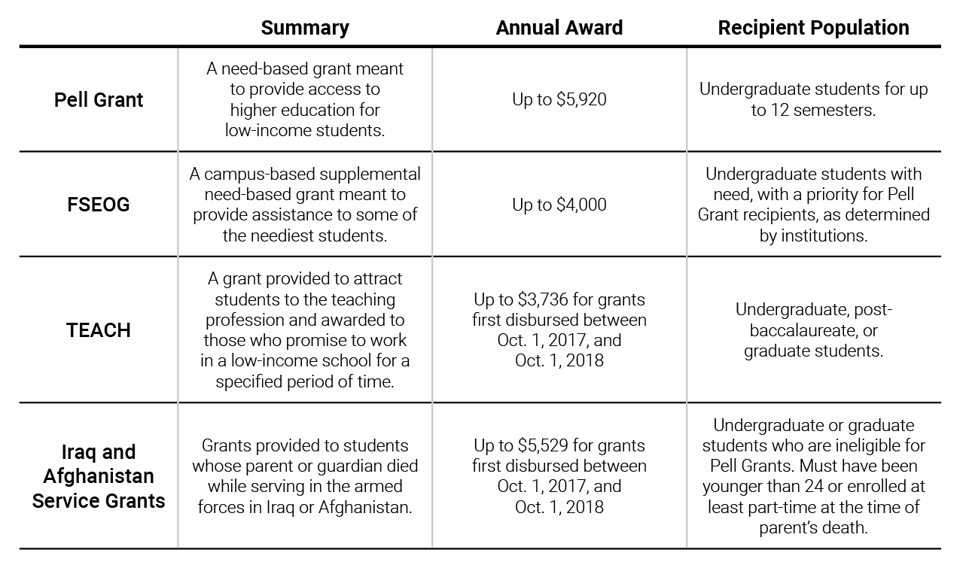

The Department of Education (Department) currently offers four grant-based programs, with the most well-known being the Federal Pell Grant Program. Pell is a need-based grant program for low- and moderate-income undergraduate students, which awards grants based on a formula that takes into account a student’s expected family contribution (EFC), cost of attendance, enrollment status (full-time or part-time), and length of academic year a student attends.8 The federal government also offers the Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (FSEOG) Program, which can serve as an enhancement to programs like Pell and help low-income students with a significant financial need. This is a campus-based aid program in which colleges and universities receive the money and in turn determine what students receive the grant and how much. Two other grants target specialized groups of students: the Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education (TEACH) Grant program, provided to students who enrolled in teacher preparation programs, and the Iraq and Afghanistan Service Grants, given to those students whose parent or guardian was a member of the U.S. armed forces serving in Iraq or Afghanistan and died as a result of their service following 9/11.

Federal Grants for Student Aid9

Loans

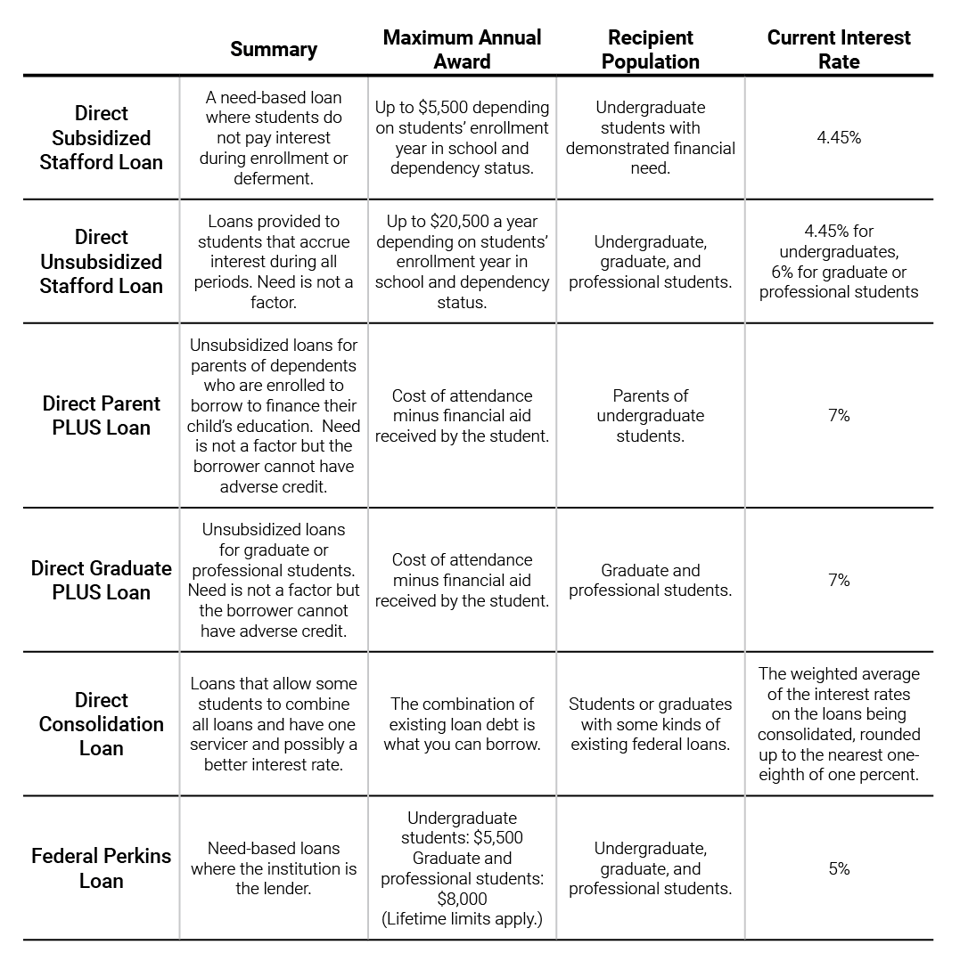

In addition to the grants currently offered to students through the federal aid system, the Department also manages two loan programs: the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan (Direct Loan) Program, sometimes referred to as Direct Stafford Loans, and the Federal Perkins Loan. Over time, the Direct Loan portfolio has grown to five different programs, each offering varying terms of service (i.e. interest rates, award amount, etc.) to various populations. For example, the Direct Subsidized Loan program allows students to defer interest payments until they are out of school, while the Direct Unsubsidized Loan program does not. PLUS loans, on the other hand, are available to less traditional populations seeking aid, like graduate students and parents of undergraduates.10 In addition, Direct Consolidation Loans allow some borrowers to combine all federal education loans into one, which allows them to have one payment with one loan servicer and a longer amount of time to repay (up to 30 years).11 Lastly, the Federal Perkins Loan Program is administered by institutions where the schools serve as the lender. These lower-interest loans are available to undergraduate, graduate, and professional students with financial need. They are low-interest loans that depend on the student’s need and the availability of the funds at the college.12 Students can utilize this program to supplement their Direct Loans if they have met their limit. However, after an extension bill stalled, Congress let the Perkins loan program expire in 2017.13

Federal Student Loans14

Federal Work Study

In addition to grants and loans, the federal government also offers the Federal Work Study program. It allocates money to institutions in the form of grants that are then passed on to provide students with on- and off-campus employment opportunities. Students are able to work in part-time positions and earn an hourly wage to help offset the costs of college, and in some cases, earn the skills they need to help find employment post-enrollment. In the 2015-2016 academic year, about 632,000 students with financial need benefited from the Federal Work Study program with an average award of $1,550.15 In most cases, the institution is responsible for funding a share of the Federal Work Study award.16

One Grant, One Loan

As this outline of available grant and loan programs shows, the federal financial aid system is complex. Students and parents have to navigate a maze of programs, not always knowing if they’re getting the best deal to meet their financial needs. That’s why some advocates for simplification have begun the calls for a one grant, one loan system that would “consolidate all existing grant programs into one Pell Grant program and all existing loan programs into one Stafford loan.”17

Specifically, “one grant, one loan” plans previously proposed look to eliminate the Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (FSEOG) and shift that money instead to the Pell Grant program. They would also end the Federal Direct Loan system and replace it with one type of loan available for all undergraduate students, graduate students, and parents or legal guardians of undergraduate students.18 These proposals also aim to eliminate the differing annual limits based on how long a student has been in school and would have similar terms to the Direct Unsubsidized Loans by not subsidizing the interest for students who are in school or in deferment. As of now, conversations around creating a “one grant, one loan” system would keep the federal work study program intact, as well as specialized programs like the TEACH Grant and the Iraq and Afghanistan Service Grants.

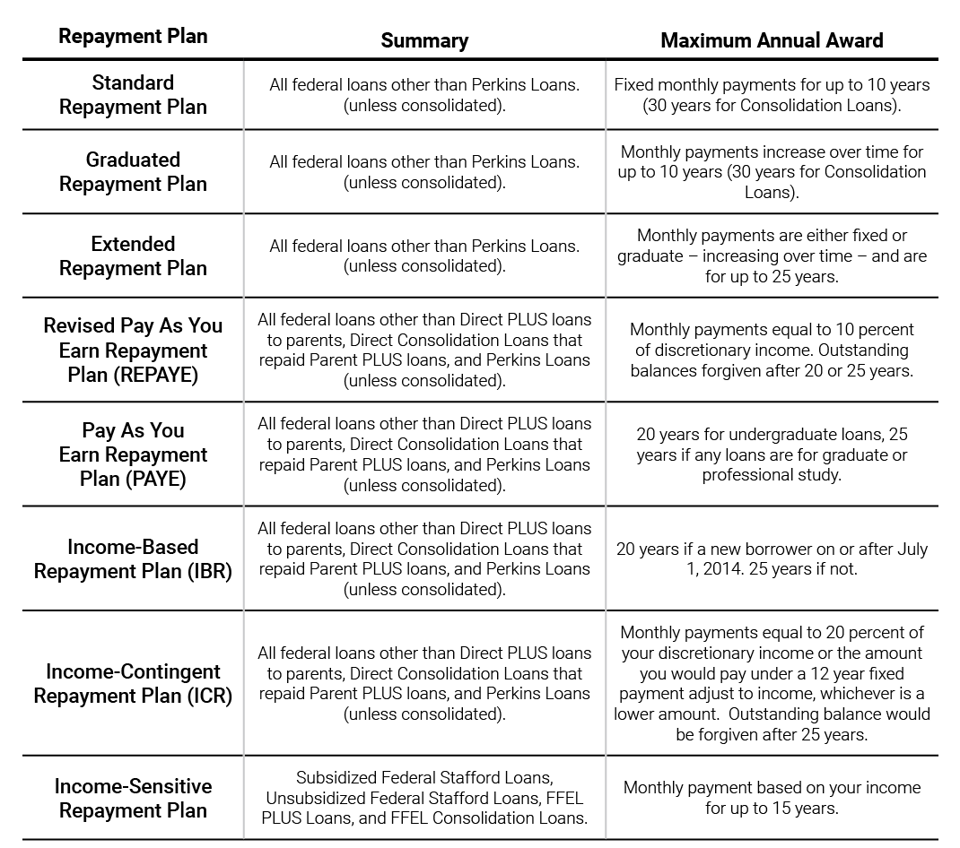

And while student financial aid is complicated on the front end, some say it’s even worse on the back end with eight different repayment options available to students today (See Appendix A). In addition to consolidating the existing grant and loan programs, it should be noted that “one grant, one loan” proposals also advocate for the simplification of repayment plans as part of the restructuring process. These proposals typically limit repayment to two options: an income-based repayment (IBR) plan and a 10-year repayment plan with standard monthly payment.

Implications of Moving to a One-Size-Fits-All System

1. Eliminating FSEOG could make it harder to target funds to those who need it the most.

Consolidating the menu of federal financial aid options into a “one grant, one loan” system is appealing on face value, but some advocates against this kind of plan argue there are unintended consequences for implementing its one-size-fits-all approach. In particular, advocates say that a diversified portfolio of loan and grant programs exists to specifically target certain populations that a slimmed down aid system could miss. For example, FSEOG supplements financial aid packages for students with the most need, specifically giving Pell Grant recipients priority. However, FSEOG works in a format similar to “last dollar” because institutions receive the money and determine who receives the grant based on their remaining need after additional grants and loans have been taken into account.19 This means that FSEOG can be used to plug gaps for students’ needs that were was not initially met. Eliminating FSEOG in favor of a Pell-only system could make it difficult to ensure schools can provide all high-need students with the financial aid necessary for them to access and complete school. If that money were reallocated to the Pell Grant program, the set of students that receive the supplemental funding could lose that needed support.

However, proponents of a “one grant, one loan” system argue that FSEOG is an inequitable distribution of grant money that is not actually targeted to begin with, as FSEOG doesn’t always get to students who need it most. Because of the way its funding formula is written, FSEOG dollars often go to elite private and public four-year institutions that tend to serve a smaller percent of low-income students than the regional state institutions and community colleges that could benefit from funding targeting a high-needs population the most.20 By shifting FSEOG funds into the Pell Grant program, proponents of its elimination argue that the government can more equitably distribute federal aid dollars to benefit students, no matter the institution.

2. Low-and moderate-income students could be disproportionately affected by the elimination of subsidized loans.

Opponents of eliminating the subsidy provided to loan borrowers as proposed under a “one grant, one loan” system argue that doing so would adversely impact the loan balances of low-income students. That’s because subsidizing the interest of undergraduate students with demonstrated financial need has historically been a way to ensure that their balances don’t balloon while they’re in school, helping make payments more manageable when their loans enter into repayment. As a result, not having interest paid for while students are enrolled means that low- and moderate-income students will actually owe more money when they graduate than the amount they originally borrowed. According to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), if a student who borrows the lifetime limit of subsidized loans “instead borrowed that amount through unsubsidized loans, that student would leave school with additional debt of about $3,400.”21 This is a real concern given a recent analysis showing the median African American borrower owed more on their student loan balance 12 years after college entry than what they initially borrowed.22

However, “one grant, one loan” supporters disagree, citing that while there would be a loss in interest savings for currently qualifying students, the current subsidized loan program benefits many more students than just those with low- and moderate-incomes. Because “need” is currently based on cost of attendance, some students with higher family incomes who attend institutions with higher tuition also receive this subsidy today. In the 2011-12 academic year, approximately one-third of subsidized loans were issued to students with families with adjusted gross incomes (AGIs) of over $50,000 a year.23 When subsidized loans for graduate students were eliminated, that money was shifted into the Pell Grant program. If the $3 billion a year spent on undergraduate subsidized loans were also shifted to the Pell Grant program, proponents argue that it would allow federal subsidies to directly reduce the amount borrowed in the first place, helping students who need it most.24

3. Getting rid of PLUS Loans could limit access to higher education for students.

Lastly, opponents of reducing the number of loan programs argue that while loans historically were meant to provide choice to students, with rising costs of college across the board, they now serve as a tool for providing access. This is true of the PLUS program, which was originally implemented to provide graduate students and parents of undergraduate students with additional financing options for attending college. While some may disagree with the premise that graduate students and parents of undergraduate students should be allowed to take out federal loans at all, proponents of maintaining the PLUS loan programs believe they can help make up the difference for students whose need is not met by their aid packages—especially among demographics of students and parents who may not be able to as easily qualify for alternative financing options. Specifically, a task force report by the National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators (NASFAA) raised the concern that the elimination of PLUS Loans might push students and families to the private loan market, leaving them worse off.25 They argue that allowing students and their families who may be viewed as risky borrowers to have additional options outside of the private loan market is important, as private loans have much less favorable terms, higher interest rates, might require payment during school, and are also dependent on income and credit scores.26

While opponents of streamlining worry it could limit access, supporters of the “one grant, one loan” approach argue that simply increasing the borrowing limits on Direct Loans rather than keeping ineffective PLUS loans in place would keep higher education accessible for all students. Specifically, they argue that because Graduate PLUS loans have no aggregate limits in place now, the program provides no incentive for students to limit their borrowing or for institutions to lower tuition. Instead, “one grant, one loan” proponents argue that capping the availability of loans will cause graduate—and perhaps undergraduate—schools to control tuition costs because students would otherwise be required to look to the private market with less generous terms to finance their educations (this idea, known as the “Bennett Hypothesis,” is named after former Secretary of Education William Bennett and stems from the belief that access to financial aid enables institutions to easily raise their tuition).27 In addition, because unlimited amounts can be borrowed and then ultimately forgiven under the current repayment plans, proponents of a “one grant, one loan” system argue that taxpayers can end up on the hook for graduate students who may not need this kind of taxpayer support.

Conclusion

With a complex menu of federal loan and grant options available today, the financial aid system is ripe for simplification. Students and their families should have fewer obstacles in understanding the gravity of the financial decision attending college requires them to make, while still having options to find an aid package that best meets their financial needs. Any streamlining to the financial aid system that does occur must focus on an approach that works to help those students who need financial assistance the most. Because above all, the federal financial aid system should make it easier for college-goers to find a financial aid package that is right for them, while still ensuring that all students have the resources they need to both access and complete postsecondary programs.

Appendix

Repayment Plans offered by the Department of Education*

*Borrowers are eligible for repayment plans based on the type of loan they received.